Soqotri language

| Soqotri | |

|---|---|

| méthel d-saqátri | |

| Pronunciation | [skˤʌtˤri][1] |

| Native to | Yemen |

| Region | Socotra |

| Ethnicity | Soqotri |

Native speakers | 70,000 (2015)[2] |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 |

sqt |

| Glottolog |

soqo1240[3] |

| |

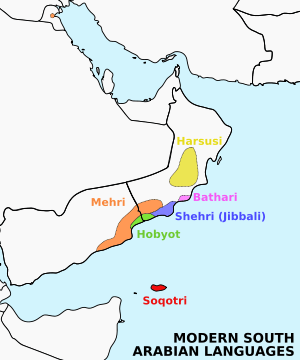

Soqotri (also spelt Socotri, Sokotri, or Suqutri; autonym: méthel d-saqátri; Arabic: اللغة السقطرية) is a South Semitic language spoken by the Soqotri people on the island of Socotra and the two nearby islands of Abd al Kuri and Samhah, in the Socotra archipelago, off the southern coast of Yemen. Soqotri is one of six languages that form a group called Modern South Arabian languages (MSAL). These additional languages include Mehri, Shehri, Bathari, Harsusi and Hobyot. All are spoken in different regions of Southern Arabia.

Classification

Soqotri is often mistaken as Arabic but is officially classified as an Afro-Asiatic, Semitic, South Semitic and South Arabian language.[4]

Status

Soqotra is still somewhat of a mystery. The island has had minimal contact with the outside world and the inhabitants of Socotra have no written history. What is known of the islands is gathered from references found in records from those who have visited the island, usually in a number of different languages, some yet to be translated. The language is thought to have its roots in Sheba, the Queen of Sheba's ancient city state on the southern Arabian mainland. During this period, the Old South Arabian languages were spoken, which also included Minaean and Qatabanian among others. The Modern South Arabian languages are not descended from the Old South Arabian languages, but they form a closely related sister group.

Endangerment

The language is under immense influence of the dominant Arabic language and culture. Because many Arabic-speaking Yemenis have settled in the Soqotri region permanently, resulting in Arabic becoming the official language of the island. Soqotri is now replaced with Arabic as a means of education in schools. Students are prohibited from using their mother tongue while at school and job seeking Soqotrans must be able to speak Arabic before getting employed. Young Soqotrans even prefer Arabic to Soqotri and now have a difficult time learning it. Oftentimes they mix Arabic in it and cannot recite or understand any piece of Soqotri oral literature.

Arabic is now the symbolic, or more ideological, articulation of the nation's identity, making it the privileged lingua franca of the nation. The government has also taken up an inclination of neglect toward the Soqotri language. This seems to based on the view that Soqotri is only a dialect rather than a language itself. There is also no cultural policy on what should be done about the remaining oral non-Arabic languages of Yemen, include Soqotri and Mehri. The language is seen as an impediment to progress because of the new generation's judgement of it as being irrelevant in helping to improve the socio-economic status of the island. Limitations to Soqotri, such as not being able to communicate through writing, are also viewed as obstacles by the youth that makes up 60% of the population. There seems to be cultural sentiments toward the language but yet an indifference due to neglect and the notion of hindrance associated with it.[5]

Hence, Soqotri is regarded as a severely endangered language and a main concern toward the lack of research in Soqotri language field is not only related to the semitics, but to the Soqotry folklore heritage conservation. This isolated island has high pressures of modernization and with a rapidly changing cultural environment, there is a possibility of losing valuable strata of the Soqotran folklore heritage.[6]

Poetry and song used to be a normal part of everyday life for people on the island, a way of communicating with others, no matter if they were human, animal, spirits of the dead, jinn sorcerers, or the divine. However, Soqotri poetry has been overlooked and the skill of the island's poets ignored.[7]

This has induced research since the nineteenth century by the United Nations Development Program in order to closely survey the island and understand its biodiversity.

The European Union has also expressed serious concerns on the issue of preserving cultural precepts of the Archipelago's population.[8]

Geographic distribution

The total population of Soqotri users throughout Yemen is 57,000 (1990 census) and total users in all countries is 71,400[9]

Official status

Soqotra is a language of Yemen where it is spoken mainly on the islands of Amanat al Asimah governorate: 'Abd al Kuri, Darsah, Samha, and Soqotra islands in the Gulf of Aden[10]

Dialects/Varieties

The Soqotri dialectology is very rich, especially considering the surface of the island and number of inhabitants. Soqotri speakers live on their islands, but rarely on the Yemeni mainland. The language was, through its history, isolated from the Arabian mainland. Arabic is also spoken in a dialectal form on Socotra.

There are four dialect groups: the dialects spoken on the north coast, the dialects spoken on the south coast, the dialects spoken by Bedouins in the mountains in the centre of the island and the dialect spkoen on cAbd al-Kuri. The dialect that is spoken on this island Samhah appears to be the same as the one spoken on the west coast of Socotra.[11]

These dialects include ’Abd Al-Kuri, Southern Soqotri, Northern Soqotri, Central Soqotri, and Western Soqotri.[12]

There are no longer any grounds for associating the (M)odern (S)outh (A)rabian languages so directly with Arabic. These dialects are not Arabic, but Semitic languages in their own right.[13]

Phonology

| Labial | Dental | Lateral | Palatal | Velar | Pharyngeal | Glottal | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| laminal | sibilant | ||||||||

| Nasal | m | n | |||||||

| Plosive | voiceless | t | k | ʔ | |||||

| voiced | b | d | ɡ | ||||||

| emphatic | tˤ~tʼ | kˤ~kʼ | |||||||

| Fricative | voiceless | f | θ | s | ɬ | ʃ | x | ħ | h |

| voiced | ð | z | ɣ | ʕ | |||||

| emphatic | sˤ~sʼ | ɬˤ~ɬʼ | ʃˤ~ʃʼ | ||||||

| Rhotic | r | ||||||||

| Semivowel | l | j | w | ||||||

| Front | Back | |

|---|---|---|

| Close | i | u |

| Mid | e | o |

| Open | ɑ |

The isolation of the island of Socotra has led to the Soqotri language independently developing certain phonetic characteristics absent in even the closely related languages of the mainland. In all the known dialects of Soqotri, there is a lack of distinction between the original South Arabic interdentals θ, ð, and θˁ and the stops t, d and ṭ: e.g. Soqotri has dərh / do:r / dɔ:r (blood), where Shehri for instance has ðor; Soqotri has ṭarb (a piece of wood), where the other South Arabian languages have forms starting with θˁ; Soqotri trih (two) corresponds to other South Arabian forms beginning with θ.

Soqotri once had ejective consonants. However, ejective fricatives have largely become pharyngeal consonants as in Arabic, and this occasionally affects the stops as well. Apart from that, the phonemic inventory is essentially identical to that of Mehri.

Grammar

Soqotri grammar and vocabulary is very poorly documented and distributed. There have been many proposals on the collection of linguistic data. This will allow a deeper understanding of the Soqotran scientific, literary, spiritual, and so on, culture native speakers. Preservation of the Soqotri language will give future generations access to this education as well.

Morphology

Independent pronouns

Independent personal pronouns for the 2nd person singular, ē (m.) and ī (f.), are more widespread than het and hit. In research done by Marie-Claude Simeone-Senelle, het and hit actually specific to some of the dialects spoken in Diksam, and the far-western areas of Qalansiya, Qafiz. She found that in other places, the 2nd singluar m. and f., are ē and ī. In the latest system, the subject pronouns are the full form.

Connective particle

Another linguistic uniqueness in the far-western dialect of Qafiz is the possessive construction. This dialect, like all other Soqotri dialects, is based in the connective d-, followed by a pronoun. However, in this dialect, the connective is variable (like the relative pronoun): d- with a singular, and l- with a plural:

dihet férham/ girl>‘your(msg.) girl’, des ‘her’..., but lḥan, ‘our’, ltan ‘your (pl.)’, lyihan ‘their (m.)’, lisan ‘their (f.)’.

This variation highlights the link between connective, deictic and relative pronoun. In other dialects, a grammaticalization process took place and the singular form was frozen as a connecting invariable particle d-.

Nominal dual

The nominal dual -in, instead of -i is a specific feature to a 15 year old boy from Diksam. It may be due to his idiolect, but the link with classical Arabic dual is interesting:

əsbá‘in ‘two fingers’; ba‘írin ‘two camels’; əsáfirōtin ‘two birds’; məkšămin ‘two boys’; but with colour names: aféri ‘red (dual)’; hări ‘black (dual)’.

Syntax

Agreement

In some dialects, the relative pronoun does not agree with plural:

le-ēfœ d-ize em b'fédəhɔn <deictic(pl.)-people/ rel.(sg)-they stay/ in-mountain> ‘this people who stays in the mountain’ (Rujed).

In remote places, old people use the verbal, nominal and pronominal dual:

eṭáyherö ho-w-d-eh ḳaḳa ḳalansíye <we go (1dual)/I-and-of-me/ brother/ Qalansiya> ‘I and my brother, we go to Qalansiya’,

but many native speakers (young people or people in contact with Arabic) do not use verbal dual regularly:

ˤeğébö təṭhár (for təṭhárö) <they want (3dual)/ go (subj. 3f.sg.) > ‘They (both) want to go’,

and they use plural pronouns instead of the dual form:

tten férhem <of-your (pl.)/girl>‘your girl’ for /tti férhem/ ‘your girl’ (to you both).

Many people in contact with Arabic tend to use plural in all cases (verb or pronoun). Only the nominal dual occurs regularly.

Negation

Cf. above, about the phono-morphological explanation for the two forms of negation. In many dialects, the verbal negation is the same with indicative and prohibitive.

Vocabulary

Lieutenant Wellstedt, who was part of a surveying mission in 1835, was the first to collect toponyms, tribe names, plant names, figures, and in total was able to put together a list of 236 Soqotri words. The words have no characteristics of the Western dialects and 41 words out of the 236 were noted as Arabic loans by Wellstedt. Some are really Arabic as beïdh (bayḍ) ‘eggs’ (ḳehélihen in Soqotri) or ˤajúz ‘old woman’ (Soqotri śíbīb), thob (tob) ‘a shirt’ (with interdental, absent from the Soqotri consonant system; tob in Soqotri means ‘cloth’); many words belong to the old common Semitic vocabulary and are attested in both Arabic and Soqotri: edahn ‘ears’ (exactly ˤídəhen), ˤaṣábi ‘fingers’ (ˤəṣābe) etc. Religious poems show influence of Arabic with borrowings from classical Arabic vocabulary and Quranic expressions.

Writing system

A writing system for the Soqotri language was developed in 2014 by a Russian team led by Dr. Vitaly Naumkin following five years of work. This writing system can be read in his book Corpus of Soqotri Oral Literature. The script is Arabic-based and transcriptions of the text appear in translated English and Arabic. This Arabic based orthography has helped passive narrators of oral lore collaborate with researchers in order to compose literature truthful to its origins.[14]

Examples

The following examples are couplets, which is the basic building block of Soqotri poetry and song. This is a straightforward humorous piece about a stingy fisherman with easy language usage that anyone on the island could easily understand.

- ber tībeb di-ģašonten / Abdullah di-halēhn

- d-iķor di-hi sode / af teķolemen ٚeyh il-ārhen

Translation:

- Everyone knows for certain that Abdullah is quite idiotic, walking here and there:

- He's concealed his fish for so long that the bluebottles are swarming all around him!

The next example is a line that most Soqotrans would not find too difficult to understand either:

- selleman enhe we-mātA / le-ha le-di-ol yahtite

- di-ol ināsah ki-yiķtīni / lot erehon ki-gizol šeber

Literal translation:

- Greet on my behalf and make certain my greetings reach the one over there who is quite without shame.

- Who does not wipe his face clean when he has eaten, just like goats when they are feeding on the šeber plants

In order to understand this piece however, the listener has to know of the significance of the šeber plants. These plants, part of the Euphorbia plant group, survive long months of dry seasons and have a milky latex which goats often feed on in times of shortage. There is no nutritious benefit to it but, it helps rid of the goats' thirst. However, when goats feed on the latex from damaged plants, it stains their muzzles and causes sores in and around the mouth.The lines were made by a women who had found out that her lover was bragging to others of his victories (he is being compared to the feeding goats). She is calling this out and warning other women to be careful of men of his like.[15]

References

- ↑ Simeone-Senelle, Marie-Claude (2010). MEHRI AND HOBYOT SPOKEN IN OMAN AND YEMEN. 07-02-2010, Symposium Yemen - Oman - Muscat.

- ↑ Soqotri at Ethnologue (19th ed., 2016)

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Soqotri". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- ↑ "Soqotri". Ethnologue. Retrieved 2017-05-04.

- ↑ Elie, Serge D. (2012-06-01). "Cultural Accommodation to State Incorporation in Yemen: Language Replacement on Soqotra Island". Journal of Arabian Studies. 2 (1): 39–57. doi:10.1080/21534764.2012.686235. ISSN 2153-4764.

- ↑ Elie, Serge D. (2016-01-01). "Communal Identity Transformation in Soqotra: From Status Hierarchy to Ethnic Ranking". Northeast African Studies. 16 (2): 23–66. doi:10.14321/nortafristud.16.2.0023. JSTOR 10.14321/nortafristud.16.2.0023.

- ↑ Morris, Miranda J. (2013-01-01). "The use of 'veiled language' in Soqoṭri poetry". Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies. 43: 239–244. JSTOR 43782882.

- ↑ "Saba Net - Yemen news agency". www.sabanews.net. Retrieved 2017-05-04.

- ↑ "Soqotri". Ethnologue. Retrieved 2017-05-04.

- ↑ "Soqotri". Ethnologue. Retrieved 2017-05-04.

- ↑ "Foundation For Endangered Languages. Home". www.ogmios.org. Retrieved 2017-05-04.

- ↑ "Soqotri". Ethnologue. Retrieved 2017-05-04.

- ↑ Smith, G. Rex (1988-01-01). "Review of Comparative Vocabulary of Southern Arabic: Mahri, Gibbali and Soqotri". Bulletin (British Society for Middle Eastern Studies). 15 (1/2): 186–186. JSTOR 195306.

- ↑ Naumkin, V. V; Kogan, Leonid Efimovich (2014-01-01). Corpus of Soqotri oral literature. ISBN 9789004278400.

- ↑ Morris, Miranda J. (2013-01-01). "The use of 'veiled language' in Soqoṭri poetry". Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies. 43: 239–244. JSTOR 43782882.

Further reading

- Alexander Militarev Semitic Language Tree with Soqotri modern classification (above)

- Wolf Leslau, Lexique Soqotri (sudarabique moderne) avec comparaisons et explications étymologiques. Paris: Klincksieck 1938

- Dr. Maximilian Bittner: Charakteristik der Sprache der Insel Soqotra Anzeiger der philosophisch-historischen Klasse der kaiserlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften in Wien. Wien, Jahrgang 1918, Nr. VIII

- Müller D.H. (1902), Die Mehri - und Soqotri - Sprache. Volume I: Texte. Südarabische Expedition, Band IV. Kaiserliche Akademie der Wissenschaften in Wien. Wien: Alfred Hölder 1902

- Müller D.H. (1905), Die Mehri - und Soqotri - Sprache. Volume II: Soqotri Texte. Südarabische Expedition, Band VI. Kaiserliche Akademie der Wissenschaften in Wien. Wien: Alfred Hölder 1905

- Müller D.H. (1907), Die Mehri - und Soqotri - Sprache. Volume II: Shauri Texte. Südarabische Expedition, Band VII. Kaiserliche Akademie der Wissenschaften in Wien. Wien: Alfred Hölder 1907

- Wagner, E.(1953). Syntax der Mehri-Sprache unter Berucksichtigung auch der anderen neusudara bischen Sprachen. Akademie-Verlag(Berlin).

- Wagner, E. (1959). Der Dialect von Abd-al-Kuri. Anthropus 54: 475-486.

- Agafonov, Vladimir. Temethel as the Brightest Element of Soqotran Folk Poetry. Folia Orientalia, vol. 42/43, 2006/07, pp. 241–249.

- RBGE Soqotra Bibliography: at RBGE and Friends of Soqotra Org. websites.

- Soqotri spoken Mehazelo (Cinderella) tale fragment with Latin transcription - MP3

- Soqotri spoken Two Brothers tale fragment with Latin transcription - MP3

- and Soqotri folk tale text publication in CLN.

- Aloufi, Amani (2016). "A Grammatical Sketch of Soqotri with Special Consideration of Negative Polarity". pp. 12-19

- Elie, S (2012). "Cultural Accommodation to State Incorporation in Yemen: Language Replacement on Soqotra Island". Journal of Arabian Studies. 2 (1): 39–57. doi:10.1080/21534764.2012.686235.

- Elie, S (2006). "Soqotra: South Arabia's Strategic Gateway and Symbolic Playground". British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies. 33 (2): 131–160. doi:10.1080/13530190600953278.

- Simeone-Senelle, MC. (2011). 64. The Modern South Arabian Languages. The Semitic Languages, 378-423.

- Simeone-Senelle, M (2003). "Soqotri dialectology and the evaluation of the language endangerment". The Developing Strategy Of Soqotra Archipelago And The Other Yemeni Islands. 14–16: 1–13.

- Shibatani, Masayoshi, and Khaled Awadh Bin Makhashen. 2009. Nominalization in Soqotri, a South Arabian language of Yemen. W. Leo Wetzels (ed.) Endangered languages: Contributions to Morphology and Morpho-syntax, 9-31.

- Marie-Claude Simeone-Senelle. (2003). Soqotri dialectology and the evaluation of the language endangerment. The Developing Strategy of Soqotra Archipelago and the other Yemeni Islands.

- Porkhomovsky, Victor (1997). "Modern South Arabian languages from a Semitic and Hamito-Semitic perspective". Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies. 27: 219–223.

- Leslau, W (1943). "South-East Semitic (Ethiopic and South-Arabic)". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 63 (1): 4. doi:10.2307/594146.

- Johnstone, T (1968). "The non-occurrence of a t- prefix in certain Socotri verbal forms". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 31 (03): 515. doi:10.1017/s0041977x00125534.

- Naumkin, V.; Porkhomovsky, V. (2003). "Oral poetry in the Soqotran socio-cultural context. The case of the ritual song "The girl and the jinn"". Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies. 33: 315–318.

- Morris, M (2013). "The use of 'veiled language' in Soqoṭri poetry". Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies. 43: 239–244.

- Naumkin, V.; Kogan, L.; Cherkashin, D.; al-Daʿrhī, A. (2012). "Towards an annotated corpus of Soqotri oral literature: the 2010 fieldwork season". Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies. 42: 261–275.