Slaughterhouse-Five

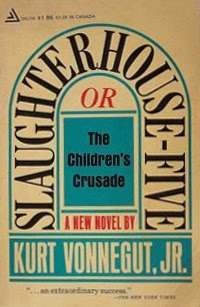

First edition cover | |

| Author | Kurt Vonnegut |

|---|---|

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre |

Dark comedy Satire Science fiction War novel Metafiction Postmodernism |

| Publisher | Delacorte |

Publication date | March 31, 1969[1] |

| ISBN | 0-385-31208-3 (first edition, hardback) |

| OCLC | 29960763 |

| LC Class | PS3572.O5 S6 1994 |

Slaughterhouse-Five, or The Children's Crusade: A Duty-Dance with Death (1969) is a science fiction-infused anti-war novel by Kurt Vonnegut about the World War II experiences and journeys through time of Billy Pilgrim, from his time as an American soldier and chaplain's assistant, to postwar and early years. It is generally recognized as Vonnegut's most influential and popular work.[2] A central event is Pilgrim's surviving the Allies' firebombing of Dresden as a prisoner-of-war. This was an event in Vonnegut's own life, and the novel is considered semi-autobiographical.

Plot

The story is told in a nonlinear order, and events become clear through flashbacks (or time travel experiences) from the unreliable narrator. He describes the stories of Billy Pilgrim, who believes he was held in an alien zoo and has experienced time travel.

Billy Pilgrim, a chaplain's assistant in the United States Army during World War II, is an ill-trained, disoriented, and fatalistic American soldier who refuses to fight ("Billy wouldn't do anything to save himself").[3] He does not like war and is captured in 1944 by the Germans during the Battle of the Bulge. Billy approaches death due to a string of events. Before the Germans capture Billy, he meets Roland Weary, a patriot, warmonger, and bully (just out of childhood like Billy), who derides the soldier's cowardice. When Weary is captured, the Germans confiscate everything he has, including his boots, giving him hinged, wooden clogs to wear; Weary eventually dies in Luxembourg of gangrene caused by wounds from the stiff clogs. While dying in a railcar full of prisoners, Weary convinces fellow soldier, Paul Lazzaro, that Billy is to blame for his death. Lazzaro vows to avenge Weary's death by killing Billy, because revenge is "the sweetest thing in life."

At this moment, Billy becomes "unstuck in time" and has flashbacks from his former life. Billy and the other prisoners are transported by the Germans to Luxembourg. By 1945, the Germans transport the prisoners to Dresden to work in "contract labor" (forced labor). The Germans hold Billy and his fellow prisoners in an empty Dresden slaughterhouse, "Schlachthof-fünf," "slaughterhouse five." During the extensive bombing by the Allies, German guards hide with the prisoners of war in a deep cellar. This results in their being among the few survivors of the firestorm that raged in the city between 13 and 15 February 1945. After V-E Day in May 1945, Billy is transferred to the United States and receives his honorable discharge in July 1945.

Soon, Billy is hospitalized with symptoms similar to post-traumatic stress disorder and placed under psychiatric care. A man named Eliot Rosewater introduces Billy to the novels of an obscure science fiction author named Kilgore Trout. After his release, Billy marries Valencia Merble. Valencia's father owns the Ilium School of Optometry that Billy later attends. In 1947, Billy and Valencia's first child, Robert, is born. Two years later their daughter Barbara is born. On Barbara's wedding night, Billy is captured by an alien space ship and taken to a planet light-years away from Earth called Tralfamadore. The Tralfamadorians are described as seeing in four dimensions, simultaneously observing all points in the space-time continuum. They universally adopt a fatalistic worldview: Death means nothing but "so it goes".

On Tralfamadore, Billy is put in a transparent geodesic dome exhibit in a zoo; the dome represents a house on Earth. The Tralfamadorians later abduct a movie star named Montana Wildhack, who had disappeared and was believed to have drowned herself in the Pacific Ocean. They intend to have her mate with Billy. She and Billy fall in love and have a child together. Billy is instantaneously sent back to Earth in a time warp to relive past or future moments of his life.

In 1968, Billy and a copilot are the only survivors of a plane crash. Valencia dies of carbon monoxide poisoning while driving to visit Billy in the hospital. Billy shares a hospital room with Bertram Rumfoord, a Harvard history professor. They discuss the bombing of Dresden, which the professor claims was justified, despite the great loss of civilian lives and destruction of the city.

Billy's daughter takes him home to Ilium. He escapes and flees to New York City. In Times Square he visits a pornographic book store. Billy discovers books written by Kilgore Trout and reads them. Later in the evening, when he discusses his time-travels to Tralfamadore on a radio talk show, he is evicted from the studio. He returns to his hotel room, falls asleep, and time-travels back to 1945 in Dresden, where the book ends.

Due to the non-chronological story telling, other parts of Billy's life are told throughout the book. After being evicted from the radio studio, Barbara treats Billy as a child and often monitors him. Robert becomes starkly anti-Communist and a Green Beret. Billy eventually dies in 1976 after giving a speech in a baseball stadium in which he predicts his own death and claims that "if you think death is a terrible thing, then you have not understood a word I've said." Billy is soon after shot by an assassin with a laser gun, commissioned by the elderly Lazzaro.

Characters

- Narrator

- Intrusive and recurring as a minor character, the narrator seems anonymous while also clearly identifying himself when he, the narrator, says: "That was I. That was me. That was the author of this book."[4] As noted above, as a soldier, Vonnegut was captured by Germans at the Battle of the Bulge and transported to Dresden. He and fellow prisoners survived the bombing while being held in a deep cellar of Schlachthof Fünf (Slaughterhouse 5).[5] The narrator begins the story describing his connection to the fire-bombing of Dresden and his reasons for writing Slaughterhouse-Five.

- Billy Pilgrim

- A fatalistic optometrist ensconced in a dull, safe marriage in Ilium, New York. During World War II, he was held as a prisoner of war in Dresden, surviving the firebombing, experiences which had a lasting effect on his post-war life. His time travel occurs at desperate times in his life; he re-lives events past and future and becomes fatalistic (though not a defeatist) because he has seen when, how and why he will die.

- Roland Weary

- A weak man dreaming of grandeur and obsessed with gore and vengeance, who saves Billy several times (despite Billy's protests) in hopes of military glory. Weary gets them captured, leading to the loss of his winter uniforms and boots. Weary dies of gangrene in the train en route to the POW camp and blames Billy in his dying words.

- Paul Lazzaro

- Another POW. A sickly, ill-tempered car thief from Cicero, Illinois, who takes Weary's dying words as a revenge commission to kill Billy. He keeps a mental list of his enemies, claiming he can have anyone "killed for a thousand dollars plus traveling expenses." Lazzaro eventually fulfills his promise to Weary and has Billy assassinated by a laser gun in 1976.

- Kilgore Trout

- A failed science fiction writer who makes money by managing newspaper delivery boys and has received only one fan letter (from Eliot Rosewater; see below). After Billy meets him in a back alley in Ilium, New York, he invites Trout to his wedding anniversary celebration. There, Kilgore follows Billy, thinking the latter has seen through a "time window." Kilgore Trout is also a main character in Vonnegut's novel Breakfast of Champions.

- Edgar Derby

- A middle-aged man who has pulled strings to be able to fight in the war. He was a high school teacher who felt that he needed to participate rather than just sending off his students to fight. Though relatively unimportant, he seems to be the only American before the bombing of Dresden to understand what war can do to people. German forces summarily execute him for looting. Vonnegut has said that this death is the climax of the book as a whole.

- Howard W. Campbell, Jr.

- An American Nazi. Before the war, he lived in Germany where he was a noted German-language playwright and Nazi propagandist. In an essay, he connects the misery of American poverty to the disheveled appearance and behavior of the American POWs. Edgar Derby confronts him when Campbell tries to recruit American POWs into the American Free Corps to fight the Communist Soviet Union on behalf of the Nazis. Campbell is the protagonist of an earlier Vonnegut novel, Mother Night.

- Valencia Merble

- Billy's wife and mother of their children, Robert and Barbara. Billy is emotionally distant from her. She dies from carbon monoxide poisoning after an automobile accident en route to the hospital to see Billy after his airplane crash.

- Robert Pilgrim

- Son of Billy and Valencia. A troubled, middle-class boy and disappointing son who so absorbs the anti-Communist world view that he metamorphoses from suburban adolescent rebel to Green Beret sergeant.

- Barbara Pilgrim

- Daughter of Billy and Valencia. She is a "bitchy flibbertigibbet," from having had to assume the family's leadership at the age of twenty. She has "legs like an Edwardian grand piano," marries an optometrist, and treats her widower father as a childish invalid.

- Tralfamadorians

- The extraterrestrial race who appear (to humans) like upright toilet plungers with a hand atop, in which is set a green eye. They abduct Billy and teach him about time's relation to the world (as a fourth dimension), fate, and death's nature. The Tralfamadorians are featured in several Vonnegut novels. In Slaughterhouse Five, they reveal that the universe will be accidentally destroyed by one of their test pilots.

- Montana Wildhack

- A model who stars in a film showing in a pornographic book store when Billy stops in to look at the Kilgore Trout novels sitting in the window. She is featured on the covers of magazines sold in the store. Abducted and placed with Billy on Tralfamadore, she has sex with him and they have a child.

- "Wild Bob"

- A superannuated army officer Billy met in the war. He dies of pneumonia. He tells his fellow POWs to call him "Wild Bob," as he thinks they're the 451st Infantry Regiment and under his command. His "If you're ever in Cody, Wyoming, ask for Wild Bob," is a phrase that Billy repeats to himself.

- Eliot Rosewater

- Billy befriends him in the veterans' hospital; he introduces Billy to the sci fi novels of Kilgore Trout. Rosewater wrote the only fan letter Trout ever received. Rosewater had also suffered a terrible event during the war. They find the Trout novels help them deal with the trauma. Rosewater is a character featured in other books by Kurt Vonnegut, such as God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater.

- Bertram Copeland Rumfoord

- A Harvard history professor, retired Air Force brigadier general and millionaire, who shares a hospital room with Billy and is interested in the Dresden bombing. He is likely a relative of Winston Niles Rumfoord, a character in Vonnegut's earlier novel, The Sirens of Titan.

- The Scouts

- Two American infantry scouts trapped behind German lines who found Roland Weary and Billy. Roland refers to him and the scouts as the "Three Musketeers." The scouts abandon Roland and Billy because the latter are slowing them down. They are revealed to have been shot and killed by Germans in ambush.

- Mary O'Hare

- The character briefly discussed in the beginning of the book, to whom Vonnegut promised to name the book The Children's Crusade. She is the wife of Bernard V. O'Hare.

- Bernard V. O'Hare

- The husband of Mary O'Hare. He is the narrator's old war friend who was also held in Dresden and accompanies him to that city after the war.

- Werner Gluck

- The sixteen-year-old German charged with guarding Billy and Edgar Derby when they are first placed at Slaughterhouse Five in Dresden. He does not know his way around and accidentally leads Billy and Edgar into a communal shower where some German refugee girls from the Eastern Front are bathing. He is described as appearing similar to Billy. They are revealed by the narrator as distant cousins but never discover this fact in the novel.

Style

The novel is simple in syntax and sentence structure, part of Vonnegut's signature style. Likewise, irony, sentimentality, black humor, and didacticism are prevalent throughout the work.[6] Like much of his oeuvre, Slaughterhouse-Five is broken into small pieces, in this case brief experiences in one point in time. Vonnegut himself has claimed that his books "are essentially mosaics made up of a whole bunch of tiny little chips...and each chip is a joke." Vonnegut also includes hand-drawn illustrations, a technique he repeated in his next novel, Breakfast of Champions (1972). Characteristically, Vonnegut makes heavy use of repetition, frequently using the phrase "So it goes" as a refrain when events of death, dying and mortality occur, as a narrative transition to another subject, as a memento mori, as comic relief, and to explain the unexplained. It appears 106 times.[7]

The book has been classified as a postmodern, metafictional novel. The first chapter of Slaughterhouse-Five is written in the style of an author's preface about how he came to write the novel. The Narrator begins the novel by telling of his connection to the Dresden bombing, and why he is recording it. He gives a description of himself, and the book, saying that it is a desperate attempt at scholarly work. He segues to the story of Billy Pilgrim: "Listen: Billy Pilgrim has come unstuck in time," thus the transition from the writer's perspective to that of the third-person, omniscient Narrator. (The use of "Listen" as an opening interjection mimics the epic poem Beowulf.) The Narrator introduces Slaughterhouse-Five with the novel's genesis and ends the first chapter by discussing the beginning and the end of the novel. The fictional "story" appears to begin in chapter two, although there is no reason to presume that the first chapter is not fiction. This technique is common to postmodern meta-fiction.[8] The story purports to be a disjointed narrative, from Billy Pilgrim's point of view, of being unstuck in time. Vonnegut's writing usually contains such disorder. He apologizes for the novel being "so short and jumbled and jangled," but says "there is nothing intelligent to say about a massacre."

The Narrator reports that Billy Pilgrim experiences his life discontinuously, so that he randomly lives (and re-lives) his birth, youth, old age, and death, rather than in customary linear order. There are two narrative threads: Billy's wartime period (interrupted with episodes from other periods and places in his life), which is mostly linear, and his discontinuous pre-war and post-war lives. Billy's existential perspective was compromised by his witnessing Dresden's destruction, although he had come "unstuck in time" before arriving in the city.[9] Slaughterhouse-Five is told in short, declarative sentences, which suggest the sense of reading a report of facts.[10]

The first sentence says: "All this happened, more or less." (In 2010 this was ranked No. 38 on the American Book Review's list of "100 Best First Lines from Novels.")[11] The opening sentences of the novel have been said to contain the aesthetic "method statement" of the entire novel.[12] The author later appears as a sick fellow prisoner in Billy Pilgrim's World War II. The Narrator notes this saying: "That was I. That was me. That was the author of this book." The story repeatedly refers to real and fictional novels and fiction; Billy reads Valley of the Dolls (1966), skims a Tralfamadorian novel, and participates in a radio talk show, part of a literary-expert panel discussing "The Death of the Novel." As in Mother Night, Vonnegut manipulates fiction and reality.

Kilgore Trout, whom Billy Pilgrim meets operating a newspaper delivery business, can be seen as Vonnegut's alter ego, though the two differ in some respects. Trout's career as a science-fiction novelist is checkered with thieving publishers, and the fictional author is unaware of his readership.

Religion and philosophy

Christian philosophy

One major philosophy presented in Vonnegut's novel is Christianity.[13] The novel discusses topics within Christianity, especially in regards to fate and free will. Billy Pilgrim experiences and applies these principles. Although the novel discusses the philosophies of Christianity, it presents a different sort of Christ figure or a different personality to the one that already exists.

The role of religion in the life of Billy Pilgrim is a key point in Slaughterhouse-Five. Toward the beginning of the novel the narrator states that Pilgrim started out in the Second World War as a chaplain's assistant "and had a meek faith in a loving Jesus which most soldiers found putrid."[14] This understanding of the Christian Jesus is challenged after the war as Pilgrim comes in contact with the work of Kilgore Trout's novel The Gospel from Outer Space. Trout's fictional novel within Slaughterhouse-Five explores the journey of a visitor from outer space who studies Christianity to determine "why Christians found it so easy to be cruel."[15] 'Cruel Christianity' presents a direct contrast to Billy's loving Jesus. Taking some of Trout's novel to heart, the narrator and Billy Pilgrim look to create a new sense of Christianity and a more human-like Jesus.

The idea of the human-Jesus is a central piece in analyzing Pilgrim's eventual struggle with fate and free will. By establishing a Christian figure that is not initially divine in nature sets a completely different tone to the overall understanding of humanity's placement with God. In David Vanderwerken's piece "Kurt Vonnegut's Slaughterhouse-Five at Forty: Billy Pilgrim - Even More a Man of Our Time," Vanderwerken states that the narrator may be calling for a "humanly centered Christianity in which Jesus is a 'nobody' (94), a 'bum' (95), a man."[16]

What Vonnegut suggests here is that Christ's divinity stands in the way of charity. If the "bum" is Everyman, then we are all adopted children of God; we are all Christs and should treat each other accordingly.[…] If Jesus is human, then He is imperfect and must necessarily be involved in direct or indirect evil. This Jesus participates fully in the human condition.[16]

There is some question of Christ's divinity and how that plays a part in Christian principles and it is suggested that the voice in the novel desires a form of collectivism where humanity looks at one another as equal parts and equal heirs of God. This human-Jesus argument within the novel stands as an effort to make humanity, whom Trout may consider to be "bums" and "nobodies," have more importance.The narration's call for a more human-Jesus and Christianity is seen in the last part of the discussion on Trout's novel where God speaks from heaven stating, "From this moment on, He [God] will punish horribly anybody who torments a bum who has no connections!"[17] Trout's novel attempts to make everybody somebody, as well as to emphasize the supposed cruelty of original Christian thinking, and how it ought to be changed.

The desire for a 'human' Jesus is not the only Biblical topic discussed in the novel. Another reference involves the story of Lot's wife disobeying and turning to look back at the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah. The narrator of that chapter, possibly seen as Vonnegut himself, claims that he loves Lot's wife doing so "because it was so human."[18] Amanda Wicks speaks on this incorporation of Lot's wife and the narrating voice stating, "Vonnegut naturally aligns himself with Lot's wife since both occupy the role of spectators shattered by the act of witnessing."[19] The narrator's alignment with Lot's wife also creates a good pretext for the understanding of Billy Pilgrim's psyche throughout the destruction of Dresden.

Along with asking moral questions, Slaughterhouse-Five is also a novel that focuses on the philosophies of fate and free will. In the novel, Billy Pilgrim tries to determine what his role in life is and what the purpose of everything going on around him is as well. When abducted by the Tralfamadorians, Pilgrim asks them why he is chosen among all the others. He questions the fate of the situation and what led up to that point. Billy Pilgrim considers his fate and actions to be a part of a larger network of actions, his future manipulated by one thing over another based on decision. All things that happen would happen for a reason. Indeed, Pilgrim's beginning mindset would suggest that he believed in free will, fate, whys, decisions and things happening for reasons. However, many of these thoughts are quickly challenged by the Tralfamadorians' ideology.

Tralfamadorian philosophy

As Billy Pilgrim becomes "unstuck in time", he is faced with a new type of philosophy. When Pilgrim becomes acquainted with the Tralfamadorians, he learns a different viewpoint concerning fate and free will. While Christianity may state that fate and free will are matters of God's divine choice and human interaction, Tralfamadorianism would disagree. According to Tralfamadorian philosophy, things are and always will be, and there is nothing that can change them. When Billy asks why they had chosen him, the Tralfamadorians reply, "Why you? Why us for that matter? Why anything? Because this moment simply is."[20] The mindset of the Tralfamadorian is not one in which fate and free will exist. Things happen because they were always destined to be happening. The narrator of the story explains that the Tralfamadorians see time all at once. This concept of time is best explained by the Tralfamadorians themselves, as they speak to Billy Pilgrim on the matter stating, "I am a Tralfamadorian, seeing all time as you might see a stretch of the Rocky Mountains. All time is all time. It does not change. It does not lend itself to warnings or explanations. It simply is."[21] After this particular conversation on seeing time, Billy makes the statement that this philosophy does not seem to evoke any sense of free will. To this, the Tralfamadorian reply that free will is a concept that, out of the "visited thirty-one inhabited planets in the universe" and "studied reports on one hundred more",[21] exists solely on Earth.

Using the Tralfamadorian passivity of fate, Billy Pilgrim learns to overlook death and the shock involved with death. Pilgrim claims the Tralfamadorian philosophy on death to be his most important lesson:

The most important thing I learned on Tralfamadore was that when a person dies he only appears to die. He is still very much alive in the past, so it is very silly for people to cry at his funeral. All moments, past, present, and future, always have existed, always will exist. ... When a Tralfamadorian sees a corpse, all he thinks is that the dead person is in bad condition in that particular moment, but that the same person is just fine in plenty of other moments. Now, when I myself hear that somebody is dead, I simply shrug and say what the Tralfamadorians say about dead people, which is "So it goes."[22]

Billy Pilgrim continues throughout the novel to use the term "so it goes" as it relates to death. The ideas behind death, fate, time, and free will are drastically different when compared to those of Christianity.

Tralfamadorian philosophy did not appear ex nihilo, but draws on many strands of thought. The idea of all time existing at once (as the Tralfamadorians experience it) can be found in sources ranging from Pre-Socratic Greek philosophy (e.g. Parmenides' monism)[23] to Neo-Classical Christian theology (e.g. Sir Thomas Browne's Religio Medici) to twentieth century popular science (e.g. repeated statements by Albert Einstein).[24] Likewise, the idea of determinism was prevalent in twentieth century philosophy[25] and Tralfamadorian passivity can be traced back to the Stoics.[26]

Allusions and references

Allusions to other works

As in other novels by Vonnegut, certain characters cross over from other stories, making cameo appearances and connecting the discrete novels to a greater opus. Fictional novelist Kilgore Trout, often an important character in other Vonnegut novels, in Slaughterhouse-Five is a social commentator and a friend to Billy Pilgrim. In one case, he is the only non-optometrist at a party, therefore, he is the odd-man-out. He ridicules everything the Ideal American Family holds true, such as Heaven, Hell, and Sin. In Trout's opinion, people do not know if the things they do turn out to be good or bad, and if they turn out to be bad, they go to Hell, where "the burning never stops hurting." Other crossover characters are Eliot Rosewater, from God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater; Howard W. Campbell, Jr., from Mother Night; and Bertram Copeland Rumfoord, relative of Winston Niles Rumfoord, from The Sirens of Titan. While Vonnegut re-uses characters, the characters are frequently rebooted and do not necessarily maintain the same biographical details from appearance to appearance. Kilgore Trout in particular is palpably a different person (although with distinct, consistent character traits) in each of his appearances in Vonnegut's work.[27][28]

Mr. Rosewater says that Fyodor Dostoyevsky's novel The Brothers Karamazov contains "everything there was to know about life." Vonnegut refers to The Marriage of Heaven and Hell when talking about William Blake, Billy's hospital mate's favorite poet.

In the Twayne's United States Authors series volume on Kurt Vonnegut, about the protagonist's name, Stanley Schatt says:

By naming the unheroic hero Billy Pilgrim, Vonnegut contrasts John Bunyan's "Pilgrim's Progress" with Billy's story. As Wilfrid Sheed has pointed out, Billy's solution to the problems of the modern world is to "invent a heaven, out of 20th century materials, where Good Technology triumphs over Bad Technology. His scripture is Science Fiction, Man's last, good fantasy".[29]

Allusions—historic, geographic, scientific, philosophical

Slaughterhouse-Five speaks of the fire-bombing of Dresden in World War II, and refers to the Battle of the Bulge, the Vietnam War, and the civil rights protests in American cities during the 1960s. Billy's wife, Valencia, has a "Reagan for President!" bumper sticker on her car, referring to Reagan's failed 1968 Republican presidential nomination campaign. Another bumper sticker is mentioned that says "Impeach Earl Warren".[30]

The slaughterhouse in which Billy Pilgrim and the other POWs are kept is also a real building in Dresden. Vonnegut was beaten and imprisoned in this building as a POW, and it is because of the meat locker in the building's basement that he (and Billy) survived the fire-bombing; the site is largely intact and protected.

The Serenity Prayer appears twice.[31] Critic Tony Tanner suggested that it is employed to illustrate the contrast between Billy Pilgrim's and the Tralfamadorians' view of fatalism.[32]

Reception

The reviews of Slaughterhouse-Five have been largely positive since the March 31, 1969 review in The New York Times newspaper that stated: "you'll either love it, or push it back in the science-fiction corner."[33] It was Vonnegut's first novel to become a bestseller, staying on the New York Times bestseller list for sixteen weeks, peaking at #4.[34] In 1970, Slaughterhouse-Five was nominated for best-novel Nebula and Hugo Awards. It lost both to The Left Hand of Darkness, by Ursula K. Le Guin. In 1998, the Modern Library ranked Slaughterhouse-Five eighteenth on its list of the 100 best English-language novels of the 20th century. It also appeared in Time magazine's list of the 100 best English-language novels written since 1923.[35]

Censorship controversy

Slaughterhouse-Five has been the subject of many attempts at censorship due to its irreverent tone, purportedly obscene content and depictions of sex, American soldiers' use of profanity, and perceived heresy. It was one of the first literary acknowledgments that homosexual men, referred to in the novel as "fairies," were among the victims of the Nazi Holocaust.[36]

In the United States it has at times been banned from literature classes, removed from school libraries, and struck from literary curricula.[37] In 1972, following the ruling of Todd v. Rochester Community Schools, it was banned from Rochester Community Schools in Oakland County, Michigan.[38] The circuit judge described the book as "depraved, immoral, psychotic, vulgar and anti-Christian."[36]

The U.S. Supreme Court considered the First Amendment implications of the removal of the book, among others, from public school libraries in the case of Island Trees School District v. Pico, 457 U.S. 853 (1982) and concluded that "local school boards may not remove books from school library shelves simply because they dislike the ideas contained in those books and seek by their removal to 'prescribe what shall be orthodox in politics, nationalism, religion, or other matters of opinion.'" Slaughterhouse-Five is the sixty-seventh entry to the American Library Association's list of the "Most Frequently Challenged Books of 1990–1999" and number forty-six on the ALA's "Most Frequently Challenged Books of 2000–2009."[37] Slaughterhouse-Five continues to be controversial. In August 2011, the novel was banned at the Republic High School in Missouri. The Kurt Vonnegut Memorial Library countered by offering 150 free copies of the novel to Republic High School students on a first come, first served basis.[39]

Criticism

The bombing of Dresden in World War II is the central event mentally affecting Billy Pilgrim, the protagonist. Within, Vonnegut says the firebombing killed 135,000 German civilians; he cites The Destruction of Dresden by David Irving.[40] Later publications place the figure between 24,000 and 40,000 and question Irving's research.[41]

Critics have accused Slaughterhouse-Five of being a quietist work, because Billy Pilgrim believes that the notion of free will is a quaint Earthling illusion.[42] The problem, according to Robert Merrill and Peter A. Scholl, is that "Vonnegut's critics seem to think that he is saying the same thing [as the Tralfamadorians]. For Anthony Burgess, "Slaughterhouse is a kind of evasion—in a sense, like J. M. Barrie's Peter Pan—in which we're being told to carry the horror of the Dresden bombing, and everything it implies, up to a level of fantasy..." For Charles Harris, "The main idea emerging from Slaughterhouse-Five seems to be that the proper response to life is one of resigned acceptance." For Alfred Kazin, "Vonnegut deprecates any attempt to see tragedy, that day, in Dresden... He likes to say, with arch fatalism, citing one horror after another, 'So it goes.'" For Tanner, "Vonnegut has... total sympathy with such quietistic impulses." The same notion is found throughout The Vonnegut Statement, a book of original essays written and collected by Vonnegut's most loyal academic fans.[42]

Adaptations

A film adaptation of the book was released in 1972. Although critically praised, the film was a box office flop. It won the Prix du Jury at the 1972 Cannes Film Festival, as well as a Hugo Award and Saturn Award. Vonnegut commended the film greatly. In 2013, Guillermo del Toro announced his intention to remake the 1972 film and work with a script by Charlie Kaufman,[43] originally hoping to release it in early 2011. Due to his involvement with The Hobbit, the project was pushed back and remains uncertain.

In 1989, a theatrical adaption premiered at the Everyman Theatre, in Liverpool, England. This was the first time the novel had been presented on stage. It was adapted for the theater by Vince Foxall and directed by Paddy Cunneen.

In 1996, another theatrical adaptation of the novel premiered at the Steppenwolf Theatre Company in Chicago. The adaptation was written and directed by Eric Simonson and featured actors Rick Snyder, Robert Breuler and Deanna Dunagan.[44] The play has subsequently been performed in several other theaters, including a January 2008 New York premiere production by the Godlight Theatre Company. An operatic adaptation by Hans-Jürgen von Bose premiered in July 1996 at the Bavarian State Opera in Munich, Germany. Billy Pilgrim II was sung by Uwe Schonbeck.[45]

In September 2009, BBC Radio 3 broadcast a feature length radio drama based on the book, which was dramatised by Dave Sheasby, featured Andrew Scott as Billy Pilgrim and was scored by the group 65daysofstatic.[46]

From June 9 to July 3, 2015, Book-It Repertory Theatre in Seattle, Washington presented an adaptation of the book by Josh Aaseng, who also directed. Actors Robert Bergin, Erik Grafton, and Todd Jefferson Moore were Billy Pilgrim at three different ages. As is Book-It's practice, every word in the production was taken directly from the text of the book.

See also

References

- ↑ Strodder, Chris (2007). The Encyclopedia of Sixties Cool. Santa Monica Press. p. 73. ISBN 9781595809865.

- ↑ "100 Best Novels". Modern Library. July 20, 1998. Retrieved March 8, 2013.

- ↑ Vonnegut, Kurt. Slaughterhouse-Five. 2009 Dial Press Trade paperback edition, 2009, p. 43

- ↑ Vonnegut, Kurt (12 January 1999). Slaughterhouse-Five. Dial Press Trade Paperback. p. 160. ISBN 978-0-385-33384-9.

- ↑ "Slaughterhouse Five". Letters of Note. November 2009. Retrieved April 27, 2015.

- ↑ Westbrook, Perry D. "Kurt Vonnegut Jr.: Overview." Contemporary Novelists. Susan Windisch Brown. 6th ed. New York: St. James Press, 1996.

- ↑ "slaughterhouse five - 101 Books". 101books.net. Archived from the original on 2014-09-11. Retrieved 2014-09-11.

- ↑ Waugh, Patricia. Metafiction: The Theory and Practice of Self-Conscious Fiction. New York: Routledge, 1988. p. 22.

- ↑ He first time-trips while escaping the Germans, in the Ardennes forest. Exhausted, he fell asleep against a tree and re-lives events from his future.

- ↑ "Kurt Vonnegut's Fantastic Faces". 'Journal of the Fantastic in the Arts'. Archived from the original on 2007-11-17. Retrieved 2007-11-10.

- ↑ "100 Best First Lines from Novels". American Book Review. The University of Houston-Victoria. Retrieved August 30, 2015.

- ↑ Jensen, Mikkel. 2016. "Janus-Headed Postmodernism: The Opening Lines of Slaughterhouse-Five," in The Explicator, 74:1 Tandfonline.com

- ↑ "The symbol of Jesus and the Cross in Slaughterhouse-Five from LitCharts - The creators of SparkNotes".

- ↑ Vonnegut, Kurt (1969). Slaughterhouse-Five or the Children's Crusade. New York, New York: Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group, Inc. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-385-31208-0.

- ↑ Vonnegut, Kurt (1969). Slaughterhouse-Five or the Children's Crusade. New York, New York: Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group Inc. p. 103. ISBN 978-0-385-31208-0.

- 1 2 Vanderwerken, David (December 5, 2012). "Kurt Vonnegut's Slaughterhouse-Five at Forty: Billy Pilgrim - Even More a Man of Our Times". Critique: Studies in Contemporary Fiction. 54 (1): 46. doi:10.1080/00111619.2010.519745.

- ↑ Vonnegut, Kurt (1969). Slaughterhouse-Five or the Children's Crusade. New York, New York: Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group Inc. pp. 104–105. ISBN 978-0-385-31208-0.

- ↑ Vonnegut, Kurt (1969). Slaughterhouse-Five or the Children's Crusade. New York, New York: Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group Inc. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-385-31208-0.

- ↑ Wicks, Amanda (May 2, 2014). "'All This Happened, More or Less': The Science Fiction of Trauma in Slaughterhouse Five". Critique: Studies in Contemporary Fiction. 55 (3): 329. doi:10.1080/00111619.2013.783786.

- ↑ Vonnegut, Kurt (1969). Slaughterhouse-Five or the Children's Crusade. New York, New York: Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group Inc. p. 73. ISBN 978-0-385-31208-0.

- 1 2 Vonnegut, Kurt (1969). Slaughterhouse-Five or the Children's Crusade. New York, New York: Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group Inc. p. 82. ISBN 978-0-385-31208-0.

- ↑ Vonnegut, Kurt (1969). Slaughterhouse-Five or the Children's Crusade. New York, New York: Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group Inc. pp. 25–26. ISBN 978-0-385-31208-0.

- ↑ Hoy, Ronald C. "Parmenides' Complete Rejection of Time." The Journal of Philosophy, vol. 91, no. 11, 1994, pp. 573–598.

- ↑ Einstein, Albert, Letter to Michele Besso's Family. Ref. Bernstein, Jeremy., A Critic at Large: Besso. The New Yorker (1989).

- ↑ Hoefer, Carl (2016). "Causal Determinism". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- ↑ Baltzly, Dirk (2014). "Stoicism". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- ↑ "Abstract" (PDF). pdfs.semanticscholar.org.

- ↑ Lerate de Castro, Jesús (1994). "The Narrative Function of Kilgore Trout and His Fictional Works in Slaughterhouse-Five" (PDF). Revista Alicantina de Estudios Ingleses. 7 (7): 115. doi:10.14198/raei.1994.7.09.

- ↑ Stanley Schatt, "Kurt Vonnegut, Jr., Chapter 4: Vonnegut's Dresden Novel: Slaughterhouse-Five.", In Twayne's United States Authors Series Online. New York: G. K. Hall & Co., 1999 Previously published in print in 1976 by Twayne Publishers.

- ↑ Vonnegut, Kurt (3 November 1991). Slaughterhouse-Five. Dell Fiction. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-440-18029-6.

- ↑ Susan Farrell; Critical Companion to Kurt Vonnegut: A Literary Reference to His Life and Work, Facts On File, 2008, Page 470.

- ↑ Tanner, Tony. 1971. "The Uncertain Messenger: A Study of the Novels of Kurt Vonnegut, Jr.", City of Words: American Fiction 1950-1970 (New York: Harper & Row), pp. 297-315.

- ↑ "Books of The Times: At Last, Kurt Vonnegut's Famous Dresden Book". New York Times. March 31, 1969. Retrieved 2007-04-13.

- ↑ Justice, Keith (1998). Bestseller Index: all books, by author, on the lists of Publishers weekly and the New York times through 1990. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland. p. 316. ISBN 978-0786404223.

- ↑ "All-TIME 100 Novels: How We Picked the List".

- 1 2 Morais, Betsy (12 August 2011). "The Neverending Campaign to Ban 'Slaughterhouse Five'". The Atlantic. Retrieved 15 June 2014.

- 1 2 "100 Most Frequently Challenged Books of 1990–1999". American Library Association. Retrieved 15 June 2014.

- ↑ "Todd v. Rochester Community Schools, 200 NW 2d 90 - Mich: Court of Appeals 1972".

- ↑ Flagg, Gordon (August 9, 2011). "Vonnegut Library Fights Slaughterhouse-Five Ban with Giveaways". American Libraries Magazine. Archived from the original on August 14, 2011 – via Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Vonnegut, Kurt (1988), Allen, William Rodney, ed., Conversations with Kurt Vonnegut (Illustrated, reprint ed.), University Press of Mississippi, p. 175, ISBN 978-0-87805-357-5

- ↑ The consensus among historians is that the number killed was between slightly under 25,000 to a few thousand over 35,000. See:

- Evans, Richard J. David Irving, Hitler and Holocaust Denial: Electronic Edition, [(i) Introduction.

- Addison (2006), p. 75.

- Taylor, Bloomsbury 2005, p. 508.

- Spiegel.de

- All three historians, Addison, Evans and Taylor, refer to:

- Bergander, Götz (1977). Dresden im Luftkrieg: Vorgeschichte-Zerstörung-Folgen. Munich: Wilhelm Heyne Verlag, who estimated a few thousand over 35,000.

- Reichert, Friedrich. "Verbrannt bis zur Unkenntlichkeit," in Dresden City Museum (ed.). Verbrannt bis zur Unkenntlichkeit. Die Zerstörung Dresdens 1945. Altenburg, 1994, pp. 40–62, p. 58. Richard Evans regards Reichert's figures as definitive. Hdot.org. For comparison, in the 9–10 March 1945 Tokyo raid by the USAAF, the most destructive firebombing raid in World War II, 16 square miles (41 km2) of the city were destroyed and some 100,000 people are estimated to have died in the conflagration. Usaaf.net Archived 2008-12-05 at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 Robert Merrill and Peter A. Scholl, Vonnegut's Slaughterhouse-Five: The Requirements of Chaos, in Studies in American Fiction, Vol. 6, No. 1, Spring, 1978, p 67.

- ↑ Sanjiv, Bhattacharya (10 July 2013). "Guillermo del Toro: 'I want to make Slaughterhouse Five with Charlie Kaufman '". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved September 20, 2015.

- ↑ "Slaughterhouse-Five: September 18 - November 10, 1996". Steppenwolf Theatre Company. 1996. Retrieved 3 October 2016.

- ↑ Couling, Della (19 July 1996). "Pilgrim's progress through space". The Independent on Sunday.

- ↑ Sheasby, Dave (20 September 2009). "Slaughterhouse 5". BBC Radio 3.

External links

- Official website

- Kurt Vonnegut discusses Slaughterhouse-Five on the BBC World Book Club

- Kilgore Trout Collection

- Photos of the first edition of Slaughterhouse-Five

- Visiting Slaughterhouse Five in Dresden

- Slaughterhous Five – Pictures of the area 65 years later

- Slaughterhouse Five digital theatre play

- The Dell Paperback Collection at the Library of Congress has four copies of Kurt Vonnegut's Slaughterhouse-Five issued under number 8029, which exhibit three markedly different covers.