Silappatikaram

Silappadikaram (Tamil: சிலப்பதிகாரம், Cilappatikāram, IPA: [ʧiləppət̪ikɑːrəm] ?, republished as The Tale of an Anklet[1]) is one of The Five Great Epics of Tamil Literature according to later Tamil literary tradition.[2] A poet-prince from Kodungallur near Kochi (part of ancient Tamilakam, now in modern Kerala), referred to by the pseudonym Ilango Adigal, is credited with this work.[3] He is reputed to have been the brother of Vel Kelu Kuttuvan, the Chera dynasty king.[4]

As a literary work, Silappatikaram is held in high regard by the Tamil people. It contains three chapters and a total of 5270 lines of poetry. The epic revolves around Kannagi, who having lost her husband to a miscarriage of justice at the court of the Pandyan Dynasty, wreaks her revenge on his kingdom.[5]

Regarded as one of the great works of Tamil literature, the Silappathikaram is a poetic rendition with details of Tamil culture; its varied religions; its town plans and city types; the mingling of different people; and the arts of dance and music.

Silappatikaram has been dated to likely belong to the beginning of Common era,[6] although the author might have built upon a pre-existing folklore to spin this tale. The story involves the three Tamil kingdoms of the ancient era, which were ruled by the Chola, Pandyan and Chera dynasties. Silappatikaram has many references to historical events and personalities, although it has not been accepted as a reliable source of history by many historians because of the inclusion of many exaggerated events and achievements to the ancient Tamil kings.

Historical and social setting

At the end of the Sangam epoch (second – third centuries CE), the Tamil country was in political confusion. The older order of the three Tamil dynasties was replaced by the invasion of the Kalabhras. These new kings and others encouraged the religions of Buddhism and Jainism. Ilango Adigal, the author of Silappatikaram, probably lived in this period and was one of the vast number of Jain and Buddhist authors in Tamil poetry.[3] These authors, perhaps influenced by their monastic faiths, wrote books based on moralistic values to illustrate the futility of secular pleasures. Silappatikaram used akaval meter (monologue), a style adopted from Sangam literature. Silappatikaram does not use the convention of regarding the land divisions becoming part of description of life among various communities of hero and heroine.[7] The epic mentions evenings, especially in the spring season, as the prime time that exacerbates the feelings of longing in those who are separated.[7] These patterns are found only in the later works of Sanskrit by Kalidasa (4th century CE).[7] These authors went beyond the nature of Sangam poems, which contain descriptions of human emotions and feelings in an abstract fashion, and employed fictional characters in a well conceived narrative incorporating personal and social ramifications thus inventing Tamil Epics.

The story of silappatikaram is set during the first few centuries of CE and narrates the events in the three Tamil kingdoms: Chera, Chola, and Pandya. It also mentions the Ilankai king Gajabahu and the Chera Senguttuvan.[8] It confirms that the northern kingdoms of Chedi, Uttarakosala, and Vajra were known to the Tamil people of the time. The epic also vividly describes the Tamil society of the period, its cities, the people's religious and folk traditions and their gods.

Author

The authorship of Silappatikaram is credited to the pseudonym Ilango Adigal ("Prince-Ascetic"). He is reputed to be the brother of Chera king Senguttuvan, although there is no evidence in the Sangam poetic works that the famous king had a brother.[10] There are also claims that Ilango Adigal was a contemporary of Sattanar, the author of Manimekalai.[11] The prologues of each of these books tell us that each was read out to the author of the other [Silappatikaram, pathigam 90]. From comparative studies between Silappatikaram and certain Buddhist and Jain works such as Nyayaprakasa, the date of Silappatikaram has been determined to be around the fifth and the sixth centuries CE.[12]

The Epic

Objectives

In the pathigam, the prologue to the book, Ilango Adigal gives the reader the gist of the book with the précis of the story. He also lays the objectives of the book ...

| “ | We shall compose a poem, with songs, To explain these truths: even kings, if they break The law, have their necks wrung by dharma; Great men everywhere commend wife of renowned fame; and karma ever Manifests itself, and is fulfilled. We shall call the poem The Cilappatikāram, the epic of the anklet, Since the anklet brings these truths to light.[13] |

” |

Main characters

- Kovalan - Son of a wealthy merchant in Puhar

- Kannagi - Wife of Kovalan

- Masattuvan - A wealthy grain merchant and the father of Kovalan

- Madhavi - A beautiful courtesan dancer

- Chitravathi - Madhavi's Mother

- Vasavadaththai - Madhavi's female friend

- Kosigan - Madhavi's messenger to Kovalan

- Madalan - A Brahmin visitor to Madurai from Puhar

- Kavunthi Adigal - A Jain nun

- Neduncheliyan - Pandya king

- Kopperundevi - Pandya Queen

Story

Silappatikaram (literally translated, "The story of the Anklet") depicts the life of Kannagi, a chaste woman who led a peaceful life with Kovalan in Puhar (Poompuhar), then the capital of Cholas. Kannagi was born in a very rich trader family under Nagarathar Community.[14][15] She was brought up with comfort and discipline. She was married to Kovalan, who was the young son of a similarly rich trader under Nagarathar Community.[14][16][15] Her life later went astray by the association of Kovalan with another woman Madhavi who was a dancer. Kovalan left Kannagi and settled at Madhavi's house. But Madhavi's mother started to get money from Kannagi in the name of Kovalan's request, without knowledge of both Kovalan and Madhavi. The loyal and astute Kannagi lost all the wealth given to them by their parents.

One fine day Madhavi unknowingly utters a line of knowledge within the song she was singing and Kovalan finds his error of leaving his wife. He immediately leaves Madhavi to rejoin Kannagi. Reluctant to go to their rich parents for help, the duo start resurrecting their life in Madurai, the capital of Pandyas. While Kannagi stays in the outskirts of Madurai, Kovalan goes to the city to sell one of Kannagi's two ruby anklets to start a business. At the same time, the royal goldsmith had stolen a pearl anklet belonging to the queen, for which he frames Kovalan. Even the very just king is reluctant to trust Kovalan, and has him beheaded for stealing the queen's pearl anklet. Kannagi went on to prove the innocence of her husband by storming into the court and breaking her other anklet to spill its rubies. The king possibly suffers a heart attack and collapses as he had uttered a false hasty judgement.[17] The queen possibly faints and falls next to the King. As the guards, soldiers, ministers, others rush to help the King and Queen, in the ensuing confusion, unnoticed, Kannagi might have possibly takes a lamp/torch and might have set fire to the palace curtains, the raging fire is supposed to have destroyed half the city of Madurai. Some might also feel that she might have invoked the curse of "Goddess Agni" to destroy the palace. Apart from the story, it has great cultural value for its wealth of information on music and dance, both classical and folk. The most important aspect of the story is that even two thousand years ago the Tamils gave Justice to all, even the mighty King was not above law. The King gave audience to Kannagi.This also shows the power of women in those days.

Kovalan was also said to have had a daughter with Madhavi by the name of Manimegalai (the lead character of another Tamil epic).[18]

Structure of Silappatikaram

Silappatikaram contains three chapters:[19]

- Puharkkandam (புகார்க் காண்டம் – Puhar chapter), which deals with the events in the Chola city of Puhar, where Kannagi and Kovalan start their married life and Kovalan leaves his wife for the courtesan Madhavi. This contains 10 cantos or divisions.

- Maduraikkandam (மதுரைக் காண்டம் – Madurai chapter), is situated in Madurai in the Pandya kingdom where Kovalan loses his life, incorrectly blamed for the theft of the queen's anklet. This contains 13 cantos.

- Vanchikkandam (வஞ்சிக் காண்டம் – Vanchi chapter), is situated in the Chera country where Kannagi ascends to the heavens. This contains 7 cantos, and each of them is made of several sub-divisions called kaathais (narrative sections of the chapters).

Literary value

The Silappatikaram, apart from being the first known epic poem in Tamil, is also important for its literary innovations. It introduces the intermingling of poetry with prose, a form not seen in previous Tamil works. It features an unusual praise of the Sun, the Moon, the river Kaveri and the city of Poompuhar at its beginning, the contemporary tradition being to praise a deity. It is also considered to be a predecessor of the Nigandu lexicographic tradition. It has 30 referred as monologues sung by any character in the story or by an outsider as his own monologue often quoting the dialogues he has known or witnessed.[20] It has 25 cantos composed in akaval meter, used in most poems in Sangam literature. The alternative for this meter is called aicirucappu (verse of teachers) associated with verse composed in learned circles.[21] Akaval is a derived form of verb akavu indicating to call or beckon. Silappatikaram is also credited to bring folk songs to literary genre, a proof of the claim that folk songs institutionalised literary culture with the best maintained cultures root back to folk origin.[21]

Preservation

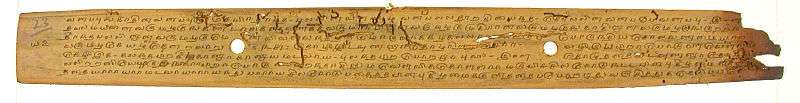

U. V. Swaminatha Iyer (1855-1942 CE) resurrected the first three epics from appalling neglect and wanton destruction of centuries.[18] He reprinted these literature present in the palm leaf form to paper books.[22] Ramaswami Mudaliar, a Tamil scholar first gave him the palm leaves of Civaka Cintamani to study.[18] Being the first time, Swaminatha Iyer had to face lot of difficulties in terms of interpreting, finding the missing leaves, textual errors and unfamiliar terms.[18] He set for tiring journeys to remote villages in search of the missing manuscripts. After years of toil, he published Civaka Cintamani in book form in 1887 CE followed by Silapadikaram in 1892 CE and Manimekalai in 1898 CE.[18] Along with the text, he added a lot of commentary and explanatory notes of terms, textual variations and approaches explaining the context.[18]

M.P. Sivagnanam popularly known as Ma. Po. Si. wrote many books on Silappatikaram, spreading the popularity of this epic considerably in the Tamil society. R. P. Sethu Pillai gave him the title 'Silambu Selvar', acknowledging the tremendous knowledge he had on this topic. Ma. Po. Si. named his daughters as Kannagi and Madhavi after the epic's characters. He instituted the Silappatikara Vizha, an annual function in 1950, which is currently headed by his daughter Madhavi after his demise.

Books written by Ma. Po. Si. on Silappatikaram include:

- Silappatikaramum Thamizharum (1947)

- Kannagi Vazhipadu (1950)

- Illangovin Silambu (1953)

- Veerakanagi (1958)

- Nenjaiallum Silappatikaram (1961)

- Madhaviyin Manbu (1968)

- Kovalan Kutravaliya (1971)

- Silappatikara Thiranaivu (1973)

- Silappatikara Yathirai (1977)

- Silappatikara Aayvurai (1979)

- Silappatikara Uraiasiriyargal Sirappu (1980)

- Silappatikarathil Yazhum isaiyum (1990)

- Silambil Edupatathu eppadi (1994)

Criticism and comparison

"After the last line of a poem, nothing follows except literary criticism" observes Ilangovadigal in Silappadikaram. The postscript invites readers to review the work. Like other epic works, it is criticised of having unfamiliar and a difficult poem to understand.[23] To some critics, Manimegalai is more interesting than Silappadikaram, but in terms of literary evaluation, it seems inferior.[24] Panicker notes that there are effusions in Silappadikaram in the form of a song or a dance, which does not go well with western audience as they are assessed to be inspired on the spur of the moment.[25] According to Calcutta review, the three epic works on a whole have no plot and no characterization to qualify for an epic genre.[26]

A review by George L. Hart , a professor of Tamil language at the University of California, Berkeley of the English translation The Tale of an Anklet by R. Parthasarathy states "The Cilappatikaram is to Tamil what the Iliad and Odyssey are to Greek—its importance would be difficult to overstate...This is an extraordinary accomplishment."[27]

Historicity

The story bears a striking resemblance to the life of the Velir chieftain of the Sangam age, Vel Avi Ko Perum Pegan, the great king Pegan of the Avi clan. Pegan was the ruler of the Palani hills also called as Tiru Avinan kudi.[28] Pegan deserted his queen Kannagi and lived with a courtesan.[29] According to history, Kannagi then appealed to poet Kapilar and the latter reunited Pegan with his queen.[30]

Popular culture

There have been multiple movies based on the story of Silappathikaram and the most famous is the portrayal of Kannagi by actress Kannamba in the 1942 movie Kannagi. P. U. Chinnappa played the lead as Kovalan. The movie faithfully follows the story of Silappathikaram and was a hit when it was released. The movie Poompuhar, penned by M. Karunanidhi is also based on Silapathikaram.[31] There are multiple dance dramas as well by some of the great exponents of Bharatanatyam in Tamil as most of the verses of Silappathikaram can be set to music.

Silappatikaram also occupies much of the screen time in the 15th and 16th episodes of the television series Bharat Ek Khoj. Pallavi Joshi played the role of Kannagi and Rakesh Dhar played that of Kovalan.

- Poompuhar (film)

- Paththini (2016 film) in Sinhala - Sri Lanka

- Kodungallooramma film in Malayalam (1968)

Rewritings

Veteran Tamil writer Jeyamohan rewrote the whole epic into a novel as Kotravai in 2005. The novel having adapted the original plot and characters, it revolves around the ancient South Indian traditions, also trying to fill the gaps in the history using multiple narratives.[32][33] The language that he crafted for this novel stands unique in the history of modern Tamil novels so far, as it uses lots of images and metaphors to narrate.[34]

H. S. Shivaprakash a leading poet and playwright in Kannada has also re-narrated a part from the epic namely Madurekanda.

Notes

- ↑ Cilappatikaram : The Tale Of An Anklet. Penguin Books India. Retrieved 13 April 2014. Silappatikaram figuratively means 'the chapter on the anklet'

- ↑ Mukherjee 1999, p. 277

- 1 2 A Survey of Kerala History. A Sreedhara Menon. 2007. p. 84. ISBN 81-264-1578-9.

- ↑ Rajarajan, R.K.K. (2016) Masterpieces of Indian Literature and Art - Tears of Kaṇṇaki: Annals and Iconology of the ‘Cilappatikāram’. Sharada Publishing House, New Delhi. Pages xix + 412, photos 143, ISBN 978-93-83221-14-1. https://www.academia.edu/30222114/Masterpieces_of_Indian_Literature_and_Art_-_Tears_of_Ka%E1%B9%87%E1%B9%87aki_Annals_and_Iconology_of_the_Cilappatik%C4%81ram_

- ↑ "Silappathikaram Tamil Literature". Tamilnadu.com. 22 January 2013. Archived from the original on 11 April 2013.

- ↑ Ilango Adigal's epic is dated to probably belong to beginning of christian era

- 1 2 3 Nadarajah 1994, p. 310

- ↑ See Codrington, H. W. A short History of Ceylon, London (1926) (http://lakdiva.org/codrington/).

- ↑ Rosen, Elizabeth S. (1975). "Prince ILango Adigal, Shilappadikaram (The anklet Bracelet), translated by Alain Damelou. Review". Artibus Asiae. 37 (1/2): 148–150. doi:10.2307/3250226. JSTOR 3250226.

- ↑ K. A. Nilakanta Sastry, A history of South India, pp 397

- ↑ Manimekalai, a Buddhist poem, tells the story of Manimekalai, the daughter of Kovalan and Madavi.

- ↑ See K. Nilakanta Sastry, A history of South India, pp 398

- ↑ Parthasarathy, translated, and with an introduction and postscript by R. (1992). The Cilappatikāram of Iḷaṅko Aṭikaḷ : an epic of South India. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 21. ISBN 023107848X.

- 1 2 Nagarathar Heritage (2017-06-07), Chettinad - Nagarathar - Ancient Town | Poompuhar | Kovalan Kannagi | Kaveripoompattinam | Chettiar, retrieved 2017-08-28

- 1 2 "Nagarathar children trace their roots". The Hindu. Retrieved 2017-08-28.

- ↑ "Welcome to Nagarathar Ikkiya Sangam". nagaratharikkiyasangam.org. Retrieved 2017-08-28.

- ↑ Rajarajan, R.K.K. (2016) Am I a King? I am the Thief – ‘yanō aracan yanē kaḷvan’. The Quarterly Journal of the Mythic Society 107.3: 1-12. ISSN 0047-8555. https://www.academia.edu/30961083/AM_I_A_KING_I_AM_THE_THIEF.pdf

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Lal 2001, pp. 4255-4256

- ↑ For Roman Transcription of the whole epic, cf. Rajarajan (2016)

- ↑ Zvelebil 1974, p. 131

- 1 2 Pollock 2003, p. 295

- ↑ M.S. 1994, p. 194

- ↑ R. 1993, p. 279

- ↑ Zvelebil 1974, p. 141

- ↑ Panicker 2003, p. 7

- ↑ University of Calcutta 1906, pp. 426-427

- ↑ "The Tale of an Anklet: An Epic of South India". Columbia University Press. Archived from the original on 14 April 2014. Retrieved 13 April 2014.

- ↑ T.A. Society (Trichinopoly, India). The Tamilian Antiquary, Volume 1, Issue 8. Asian Educational Services, 1986. p. 56.

- ↑ Adyar Library, Adyar Library and Research Centre. Brahmavidyā: The Adyar Library Bulletin, Volumes 44-45. Adyar Library and Research Centre., 1981. p. 270.

- ↑ Ve Pālāmpāḷ. Studies in the History of the Sangam Age. Kalinga Publications, 1998 - Tamil Nadu (India) - 110 pages. p. 97.

- ↑ http://movies.msn.com/movies/movie/kannagi/

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑

References

- Adigal, Ilango. "cilappatikAram of iLangkO atikaL part 2: maturaik kANTam" (PDF). projectmadurai.org. Retrieved 2011-12-13.

- Adigal, Ilango. "cilappatikAram of iLangkO atikaL part 3: vanjcik kANTam" (PDF). projectmadurai.org. Retrieved 2011-12-13.

- Codrington, H. W. A short History of Ceylon, London (1926) (http://lakdiva.org/codrington/).

- Krishnamurti, C. R., Thamizh Literature Through the Ages, Vancouver, B. C. Canada (http://tamilnation.co/literature/krishnamurti/02sangam.htm)

- Lal, Mohan; Sāhitya Akādemī (2001). The Encyclopaedia Of Indian Literature (Volume Five) (Sasay To Zorgot), Volume 5. New Delhi: Sāhitya Akādemī. ISBN 81-260-1221-8.

- Minatchisuntharan, T. P. History of Tamil Literature. Annamalai University Publications in linguistics, 3. Annamalai University,1965)

- Mukherjee, Sujit (1999). A Dictionary of Indian Literature: Beginnings-1850. New Delhi: Orient Longman Limited. ISBN 81-250-1453-5.

- Nilakanta Sastri, K. A. (1955). A History of South India, OUP, New Delhi (Reprinted 2002).

- Panicker, K. Ayyappa (2003). A Primer of Tamil Literature. New Delhi: Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts. ISBN 81-207-2502-6.

- Pillai, M. S. Purnalingam (1904). A Primer of Tamil Literature. Madras: Ananda Press.

- Pillai, M. S. Purnalingam (1994). Tamil Literature. Asian Educational Services. p. 115. ISBN 978-81-206-0955-6.

- Pollock, Sheldon I. (2003). Literary cultures in history: reconstructions from South Asia. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-22821-9.

- R., Parthasarathy (1993). The Cilappatikaram of Ilanko Atikal: An Epic of South India. Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-07849-8.

- University of Calcutta (1906), Calcutta review, Volume 123, London: The Edinburgh Press .

Rajarajan, R.K.K. (2016) Masterpieces of Indian Literature and Art - Tears of Kaṇṇaki: Annals and Iconology of the ‘Cilappatikāram’. Sharada Publishing House, New Delhi. Pages xix + 412, photos 143, ISBN 978-93-83221-14-1.

- Zvelebil, Kamil (1974). A History of Indian literature Vol.10 (Tamil Literature). Otto Harrasowitz. ISBN 3-447-01582-9.

- Dr. Shuddhananda, Bharati; Dr. J. Parthasarathi (2010). Silambu Selvam a synopsis of Silappadikaram written by Dr. Shuddhananda Bharati translated from Tamil Chilambu Chelvam by Dr. J. Parthasarathi M.A., Ph.D. (PDF). Editions ASSA, L'Auberson, Switzerland. ISBN 978-2-940393-12-1.

Further reading

- Silapadatikaram in Hindi PDF on Internet archive

- Part One of Silappathikaram in pdf form

- Part Two of Silappathikaram in pdf form

- Part Three of Silappathikaram in pdf form

- Tamil Nadu's Silapathikaram Epic of the Ankle Bracelet: Ancient Story and Modern Identity by Eric Miller

- The Silappatikaram of Ilanko Atikal: An Epic of South India (Translations from the Asian Classics) by R. Parthasarathy (1992) and R.K.K. Rajarajan (2016) Masterpieces of Indian Literature and Art - Tears of Kaṇṇaki: Annals and Iconology of the ‘Cilappatikāram’ (Roman Transcriptions). Sharada Publishing House, New Delhi.

- An Introduction to Cilappathikaram

- Cilapathikaram in Tamil Unicode - pukaark kaaNtam, maturaik kANTam, vanjcik kANTam

- English Translations of Sangam Literature and Silapathikaram

- The song in Aichiyar Kuravai from Silappathikaram

- Silapathikaram website

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Silappatikaram. |