Shimabara Rebellion

| Shimabara Rebellion | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the early Edo period | |||||||

Siege of Hara Castle | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| Roman Catholics and rōnin rebels | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Amakusa Shirō † Arie Kenmotsu † Masuda Yoshitsugu † Ashizuga Chuemon † Yamada Emosaku. | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 200,000+[1] | 35,000–37,000[1] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

21,800 casualties

| 27,000+ killed | ||||||

The Shimabara Rebellion (島原の乱 Shimabara no ran) was an uprising in what is now Nagasaki Prefecture in southwestern Japan lasting from December 17, 1637, to April 15, 1638, during the Edo period. It largely involved peasants, most of them Catholics.

It was one of only a handful of instances of serious unrest during the relatively peaceful period of the Tokugawa shogunate's rule.[2] In the wake of the Matsukura clan's construction of a new castle at Shimabara, taxes were drastically raised, which provoked anger from local peasants and rōnin (samurai without masters). Religious persecution of the local Catholics exacerbated the discontent, which turned into open revolt in 1637. The Tokugawa Shogunate sent a force of over 125,000 troops to suppress the rebels and, after a lengthy siege against the rebels at Hara Castle, defeated them.

In the wake of the rebellion, the Catholic rebel leader Amakusa Shirō was beheaded and the prohibition of Christianity was strictly enforced. Japan's national seclusion policy was tightened and official persecution of Christianity continued until the 1850s. Following the successful suppression of the rebellion, the daimyō of Shimabara, Matsukura Katsuie, was beheaded for misruling, becoming the only daimyō to be beheaded during the Edo period.

Leadup and outbreak

In the mid-1630s, the peasants of the Shimabara Peninsula and Amakusa, dissatisfied with overtaxation and suffering from the effects of famine, revolted against their lords. This was specifically in territory ruled by two lords: Matsukura Katsuie of the Shimabara Domain, and Terasawa Katataka of the Karatsu Domain.[3] Those affected also included fishermen, craftsmen and merchants. As the rebellion spread, it was joined by rōnin (masterless samurai) who once had served families, such as the Amakusa and Shiki, who had once lived in the area, as well as former Arima clan and Konishi retainers.[3] As such, the image of a fully "peasant" uprising is also not entirely accurate.[4]

Shimabara was once the domain of the Arima clan, which had been Christian; as a result, many locals were also Christian. The Arima were moved out in 1614 and replaced by the Matsukura.[5] The new lord, Matsukura Shigemasa, hoped to advance in the shogunate hierarchy, and so he was involved with various construction projects, including the building and expansion of Edo Castle, as well as a planned invasion of Luzon in the Spanish East Indies (today a part of the Philippines). He also built a new castle at Shimabara.[6] As a result, he placed a greatly disproportionate tax burden on the people of his new domain and further angered them by strictly persecuting Christianity.[6] The policies were continued by Shigemasa's heir, Katsuie.

The inhabitants of the Amakusa Islands, which had been part of the fief of Konishi Yukinaga, suffered the same sort of persecution at the hands the Terasawa family, which, like the Matsukura, had been moved there.[7] Other masterless samurai in the region included former retainers of Katō Tadahiro and Sassa Narimasa, both of whom had once ruled parts of Higo Province.

Rebellion

Start

.jpg)

The discontented rōnin of the region, as well as the peasants, began to meet in secret and plot an uprising; this broke out on December 17, 1637,[8] when the local daikan (tax official) Hayashi Hyōzaemon was assassinated. At the same time, others rebelled in the Amakusa Islands. The rebels quickly increased their ranks by forcing all in the areas they took to join in the uprising. A charismatic 16-year-old youth, Amakusa Shirō, was soon chosen as the rebellion's leader.[9]

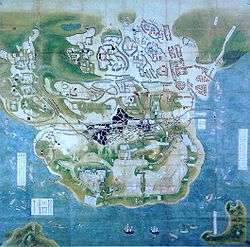

The rebels laid siege to the Terasawa clan's Tomioka and Hondo castles, but just before the castles were about to fall, armies from the neighboring domains in Kyūshū arrived, and forced them to retreat. The rebels then crossed the Ariake Sea and briefly besieged Matsukura Katsuie's Shimabara Castle, but were again repelled. At this point they gathered on the site of Hara Castle, which had been the castle of the Arima clan before their move to the Nobeoka Domain, but was dismantled.[10] They built up palisades using the wood from the boats they had crossed the water with, and were greatly aided in their preparations by the weapons, ammunition, and provisions they had plundered from the Matsukura clan's storehouses.[11]

Siege at Hara Castle

The allied armies of the local domains, under the command of the Tokugawa shogunate with Itakura Shigemasa as commander-in-chief, then began their siege of Hara Castle. The swordsman Miyamoto Musashi was present in the besieging army, in an advisory role to Hosokawa Tadatoshi.[12] The event where Musashi was knocked off his horse by a stone thrown by one of the peasants is one of the only few verifiable records of him taking part in a campaign.

The shogunate troops then requested aid from the Dutch, who first gave them gunpowder, and then cannons.[13] Nicolaes Couckebacker, Opperhoofd of the Dutch factory on Hirado, provided the gunpowder and cannons, and when the shogunate forces requested that he send a vessel, he personally accompanied the vessel de Ryp to a position offshore, near Hara Castle.[13] The cannons sent previously were mounted in a battery, and an all-out bombardment of the fortress commenced, both from the shore guns as well as from the 20 guns of the de Ryp.[14] These guns fired approximately 426 rounds in the space of 15 days, without great result, and two Dutch lookouts were shot by the rebels.[15] The ship withdrew at the request of the Japanese, following contemptuous messages sent by the rebels to the besieging troops:

Are there no longer courageous soldiers in the realm to do combat with us, and weren't they ashamed to have called in the assistance of foreigners against our small contingent?[16]

Final push and fall

In an attempt to take the castle, Itakura Shigemasa was killed. More shogunate troops under Matsudaira Nobutsuna, Itakura's replacement, soon arrived.[17] However, the rebels at Hara Castle resisted the siege for months and caused the shogunate heavy losses. Both sides had a hard time fighting in winter conditions. On February 3, 1638, a rebel raid killed 2,000 warriors from the Hizen Domain. However, despite this minor victory, the rebels slowly ran out of food, ammunition and other provisions.

By April 1638, there were over 27,000 rebels facing about 125,000 shogunate soldiers.[18] Desperate rebels mounted an assault against them on April 4 and were forced to withdraw. Captured survivors and the fortress' rumored sole traitor, Yamada Emosaku, revealed the fortress was out of food and gunpowder.

On April 12, 1638, troops under the command of the Kuroda clan of Hizen stormed the fortress and captured the outer defenses.[15] The rebels continued to hold out and caused heavy casualties until they were routed on April 15.[19]

Forces present at Shimabara

The Shimabara rebellion was the first massive military effort since the Siege of Osaka where the shogunate had to supervise an allied army made up of troops from various domains. The first overall commander, Itakura Shigemasa, had 800 men under his direct command; his replacement, Matsudaira Nobutsuna, had 1,500. Vice-commander Toda Ujikane had 2,500 of his own troops. 2,500 samurai of the Shimabara Domain were also present. The bulk of the shogunate's army was drawn from Shimabara's neighboring domains. The largest component, numbering over 35,000 men, came from the Saga Domain, and was under the command of Nabeshima Katsushige. Second in numbers were the forces of the Kumamoto and Fukuoka domains; 23,500 men under Hosokawa Tadatoshi and 18,000 men under Kuroda Tadayuki, respectively. From the Kurume Domain came 8,300 men under Arima Toyouji; from the Yanagawa Domain 5,500 men under Tachibana Muneshige; from the Karatsu Domain, 7,570 under Terasawa Katataka; from Nobeoka, 3,300 under Arima Naozumi; from Kokura, 6,000 under Ogasawara Tadazane and his senior retainer Takada Matabei; from Nakatsu, 2,500 under Ogasawara Nagatsugu; from Bungo-Takada, 1,500 under Matsudaira Shigenao, and from Kagoshima, 1,000 under Yamada Arinaga, a senior retainer of the Shimazu clan. The only non-Kyushu forces, apart from the commanders' personal troops, were 5,600 men from the Fukuyama Domain, under the command of Mizuno Katsunari,[20] Katsutoshi, and Katsusada. There was also a small number of troops from various other locations amounting to 800 men. In total, the shogunate's army comprised over 125,800 men. Conversely, the strength of the rebel forces is not precisely known. Combatants are estimated to have numbered over 14,000, noncombatants who sheltered in the castle during the siege were over 13,000. One source estimates the total size of the rebel force as somewhere between 27,000 and 37,000, a fraction of the size of the force sent by the shogunate.[8]

Aftermath

After the castle fell, the shogunate forces beheaded an estimated 37,000 rebels and sympathizers. Amakusa Shirō's severed head was taken to Nagasaki for public display, and the entire complex at Hara Castle was burned to the ground and buried together with the bodies of all the dead.[20]

Because the shogunate suspected that European Catholics had been involved in spreading the rebellion, Portuguese traders were driven out of the country. The policy of national seclusion was made more strict by 1639.[21] An existing ban on the Christian religion was then enforced stringently, and Christianity in Japan survived only by going underground.[22]

Another part of the shogunate's actions after the rebellion was to excuse the clans which had aided its efforts militarily from the building contributions which it routinely required from various domains.[23] However, Matsukura Katsuie's domain was given to another lord, Kōriki Tadafusa, and Matsukura began to be pressured by the shogunate to commit honourable ritual suicide, called seppuku.[15] However, after the body of a peasant was found in his residence, proving his misrule and brutality, Matsukura was beheaded in Edo. The Terazawa clan survived, but died out almost 10 years later, due to Katataka's lack of a successor.[24]

On the Shimabara peninsula, most towns experienced a severe to total loss of population as a result of the rebellion. In order to maintain the rice fields and other crops, immigrants were brought from other areas across Japan to resettle the land. All inhabitants were registered with local temples, whose priests were required to vouch for their members' religious affiliation.[25] Following the rebellion, Buddhism was strongly promoted in the area. Certain customs were introduced which remain unique to the area today. Towns on the Shimabara peninsula also continue to have a varied mix of dialects due to the mass immigration from other parts of Japan.

With the exception of periodic, localized peasant uprisings, the Shimabara Rebellion was the last large-scale armed clash in Japan until the 1860s.[26]

Notes

- 1 2 3 "WISHES". Uwosh.edu. 1999-02-05. Retrieved 2018-04-15.

- ↑ Borton, Japan's Modern Century, p. 18.

- 1 2 Murray, Japan, pp. 258–259.

- ↑ De Bary et al. Sources of Japanese Tradition: From Earliest Times to 1600, p. 150. "...a peasant uprising, known in history as the Shimabara Rebellion, that swept the area..."

- ↑ Murray, p. 258.

- 1 2 Naramoto (1994), Nihon no Kassen, p. 394.

- ↑ Murray, p. 259.

- 1 2 Morton, Japan: Its History and Culture, p. 260.

- ↑ Naramoto (1994), p. 395.

- ↑ Naramoto (2001) Nihon no Meijōshū, pp. 168–169.

- ↑ Naramoto (1994), p. 397; Perrin, Giving Up the Gun, p. 65.

- ↑ Harris, Introduction to A Book of Five Rings, p. 18.

- 1 2 Murray, p. 262.

- ↑ Murray, pp. 262–264.

- 1 2 3 Murray, p. 264.

- ↑ Doeff, Recollections of Japan, p. 26.

- ↑ Harbottle, Dictionary of Battles, p. 13.

- ↑ Naramoto (1994), p. 399.

- ↑ Gunn, Geoffrey (2017). World Trade Systems of the East and West. Brill. p. 134. ISBN 9789004358560.

- 1 2 Naramoto (1994), p. 401.

- ↑ Mason, A History of Japan, pp. 204–205.

- ↑ Morton, p. 122.

- ↑ Bolitho, Treasures among Men, p. 105.

- ↑ "Karatsu domain on "Edo 300 HTML"". Retrieved 2008-10-05.

- ↑ Bellah, Tokugawa Religion, p. 51.

- ↑ Bolitho, p. 228.

See also

References

English

- Bellah, Robert N. (1957). Tokugawa Religion. (New York: The Free Press).

- Bolitho, Harold. (1974). Treasures Among Men: The Fudai Daimyo in Tokugawa Japan. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-01655-0; OCLC 185685588

- Borton, Hugh (1955). Japan's Modern Century. (New York: The Ronald Press Company).

- DeBary, William T., et al. (2001). Sources of Japanese Tradition: From Earliest Times to 1600. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Doeff, Hendrik (2003). Recollections of Japan. Translated and Annotated by Annick M. Doeff. (Victoria, B.C.: Trafford).

- Harbottle, Thomas Benfield (1904). Dictionary of Battles from the Earliest Date to the Present Time. (London: Swan Sonnenschein & Co. Ltd.)

- Harris, Victor (1974). Introduction to A Book of Five Rings. (New York: The Overlook Press).

- Mason, R.H.P. (1997). A History of Japan. North Clarendon: Tuttle Publishing.

- Morton, William S. (2005). Japan: Its History and Culture. (New York: McGraw-Hill Professional).

- Murray, David (1905). Japan. (New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons).

- Perrin, Noel (1979). Giving Up the Gun: Japan's Reversion to the Sword, 1543-1879. (Boston: David R. Godine, Publisher)

Japanese

- "Karatsu domain on "Edo 300 HTML"". Retrieved 2008-10-05.

- Naramoto Tatsuya (1994). Nihon no kassen: monoshiri jiten. (Tokyo: Shufu to Seikatsusha).

- Naramoto Tatsuya (2001). Nihon meijōshū. (Tokyo: Gakken).

Further reading

- Clements, Jonathan (2016). Christ's Samurai: The True Story of the Shimabara Rebellion. (London: Robinson).

- Morris, Ivan (1975). The nobility of failure: tragic heroes in the history of Japan. (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston).

- Sukeno Kentarō (1967). Shimabara no Ran. (Tokyo: Azuma Shuppan).

- Toda Toshio (1988). Amakusa, Shimabara no ran: Hosokawa-han shiryō ni yoru. (Tokyo: Shin Jinbutsu Ōraisha).