Self-assembly of nanoparticles

Self-assembly is a phenomenon where the components of a system assemble themselves to form a larger functional unit. This spontaneous organization can be due to direct specific interaction, collective effects, and/or occur indirectly through their environment. Due to the proliferation of nanoparticle synthesis techniques, the study and design of nanoparticle self-assembly has become widespread.[2] The spatial arrangements of these self-assembled nanoparticles can be potentially used to build increasingly complex structures[3] leading to a wide variety of materials that can be used for different purposes.[4][5]

At the molecular level, intermolecular force hold the spontaneous gathering of molecules into a well-defined and stable structure together. In chemical solutions, self-assembly is an outcome of random motion of molecules and the affinity of their binding sites for one another. In the area of nanotechnology, developing a simple, efficient method to organize molecules and molecular clusters into precise, pre-determined structure is crucial.[6]

History

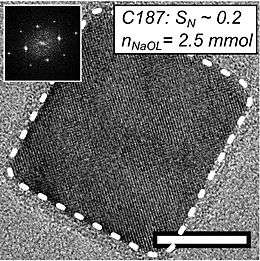

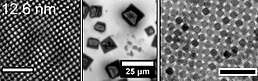

The study of self-assembly of nanoparticles began with recognition that some properties of atoms and molecules enable them to arrange themselves into patterns. A variety of applications where the self-assembly of nanoparticles might be useful. For example, building sensors or computer chips. Nanoparticles have been observed by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) to self-assemble in real-time.

Thermodynamics

Self-assembly is an equilibrium process, i.e. the individual and assembled components exist in equilibrium.[7] In addition, the lower free energy is usually a result of a weaker intermolecular force between self-assembled moieties and is essentially enthalpic in nature.

The thermodynamics of the self-assembly process can be represented by a simple Gibbs free energy equation:

where if is negative, self-assembly is a spontaneous process. is the enthalpy change of the process and is largely determined by the potential energy/intermolecular forces between the assembling entities. is the change in entropy associated with the formation of the ordered arrangement. In general, the organization is accompanied by a decrease in entropy and in order for the assembly to be spontaneous the enthalpy term must be negative and in excess of the entropy term.[7] This equation shows that as the value of approaches the value of and above a critical temperature, the self-assembly process will become progressively less likely to occur and spontaneous self-assembly will not happen.

The self-assembly is governed by the normal processes of nucleation and growth. Small assemblies are formed because of their increased lifetime as the attractive interactions between the components lower the Gibbs free energy. As the assembly grows, the Gibbs free energy continues to decrease until the assembly becomes stable enough to last for a long period of time. The necessity of the self-assembly to be an equilibrium process is defined by the organization of the structure which requires non-ideal arrangements to be formed before the lowest energy configuration is found.

Defects

Self-assembled structure contain defects. In most cases, the thermodynamic driving force for self-assembly is provided by weak intermolecular interactions and is usually of the same order of magnitude as the entropy term.[7] In order for a self-assembling system to reach the minimum free energy configuration, there has to be enough thermal energy to allow the mass transport of the self-assembling molecules. For defect formation, the free energy of single defect formation is given by:

The enthalpy term, does not necessarily reflect the intermolecular forces between the molecules, it is the energy cost associated with disrupting the pattern and may be thought of as a region where optimum arrangement does not occur and the reduction of enthalpy associated with ideal self-assembly did not occur. An example of this can be seen in a system of hexagonally packed cylinders where defect regions of lamellar structure exist.

If is negative, there will be a finite number of defects in the system and the concentration will be given by:

N is the number of defects in a matrix of N0 self-assembled particles or features and is the activation energy of defect formation. The activation energy, , should not be confused with . The activation energy represents the energy difference between the initial ideally arranges state and a transition state towards the defective structure. At low defect concentrations, defect formation is entropy driven until a critical concentration of defects allows the activation energy term to compensate for entropy. There is usually an equilibrium defect density indicated at the minimum free energy. The activation energy for defect formation increases this equilibrium defect density.[7]

Particle Interaction

Intermolecular forces govern the particle interaction in self-assembled systems. The forces tend to be intermolecular in type rather than ionic or covalent because ionic or covalent bonds will “lock” the assembly into non-equilibrium structures. The types intermolecular forces seen in self-assembly processes are van der Waals, hydrogen bonds, and weak polar forces, just to name a few. In self-assembly, regular structural arrangements are frequently observed, therefore there must be a balance of attractive and repulsive between molecules otherwise an equilibrium distance will not exist between the particles. The repulsive forces can be electron cloud-electron cloud overlap or electrostatic repulsion.[7]

Processing

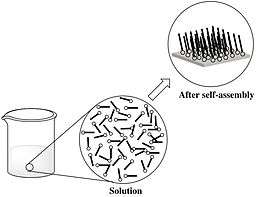

The processes by which nanoparticles self-assemble are widespread and important. Understanding why and how self-assembly occurs is key in reproducing and optimizing results. Typically, nanoparticles will self-assemble for one or both of two reasons: molecular interactions and external direction.[8]

Self-assembly by molecular interactions

Nanoparticles have the ability to assemble chemically through covalent or noncovalent interactions with their capping ligand.[9] The terminal functional group(s) on the particle are known as capping ligands. As these ligands tend to be complex and sophisticated, self-assembly can provide a simpler pathway for nanoparticle organization by synthesizing efficient functional groups. For instance, DNA oligomers have been a key ligand for nanoparticle building blocks to be self-assembling via sequence-based specific organization.[10] However, to deliver precise and scalable (programmable) assembly for a desired structure, a careful positioning of ligand molecules onto the nanoparticle counterpart should be required at the building block (precursor) level,[11][12][13][14] such as direction, geometry, morphology, affinity, etc.The successful design of ligand-building block units can play an essential role in manufacturing a wide-range of new nano systems, such as nanosensor systems,[15] nanomachines/nanobots, nanocomputers, and many more uncharted systems.

Intermolecular forces

Nanoparticles can self-assemble as a result of their intermolecular forces. As systems look to minimize their free energy, self-assembly is one option for the system to achieve its lowest free energy thermodynamically.[8] Nanoparticles can be programmed to self-assemble by changing the functionality of their side groups, taking advantage of weak and specific intermolecular forces to spontaneously order the particles. These direct interparticle interactions can be typical intermolecular forces such as hydrogen bonding or Van der Waals forces, but can also be internal characteristics, such as hydrophobicity or hydrophilicity. For example, lipophilic nanoparticles have the tendency to self-assemble and form crystals as solvents are evaporated.[8] While these aggregations are based on intermolecular forces, external factors such as temperature and pH also play a role in spontaneous self-assembly.

Hamaker interaction

As nanoparticle interactions take place on a nanoscale, the particle interactions must be scaled similarly. Hamaker interactions take into account the polarization characteristics of a large number of nearby particles and the effects they have on each other. Hamaker interactions sum all of the forces between all particles and the solvent(s) involved in the system. While Hamaker theory generally describes a macroscopic system, the vast number of nanoparticles in a self-assembling system allows the term to be applicable. Hamaker constants for nanoparticles are calculated using Lifshitz theory, and can often be found in literature.

| Material | A131 |

|---|---|

| Fe3O4[16] | 22 |

| -Fe2O3[16] | 26 |

| α-Fe2O3[16] | 29 |

| Ag[17] | 33 |

| Au[18] | 45 |

| All values reported in zJ [16] [17] [18] | |

Externally directed self-assembly

The natural ability of nanoparticles to self-assemble can be replicated in systems that do not intrinsically self-assemble. Directed self-assembly (DSA) attempts to mimic the chemical properties of self-assembling systems, while simultaneously controlling the thermodynamic system to maximize self-assembly.

Electric and magnetic fields

External fields are the most common directors of self-assembly. Electric and magnetic fields allow induced interactions to align the particles.[19] The fields take advantage of the polarizability of the nanoparticle and its functional groups.[8] When these field-induced interactions overcome random Brownian motion, particles join to form chains and then assemble. At more modest field strengths, ordered crystal structures are established due to the induced dipole interactions. Electric and magnetic field direction requires a constant balance between thermal energy and interaction energies.

Flow fields

Common ways of incorporating nanoparticle self-assembly with a flow include Langmuir-Blodgett, dip coating, flow coating and spin coating.[20]

Macroscopic viscous flow

Macroscopic viscous flow fields can direct self-assembly of a random solution of particles into ordered crystals. However, the assembled particles tend to disassemble when the flow is stopped or removed.[8][19] Shear flows are useful for jammed suspensions or random close packing. As these systems begin in nonequilibrium, flow fields are useful in that they help the system relax towards ordered equilibrium. Flow fields are also useful when dealing with complex matrices that themselves have rheological behavior. Flow can induce anisotropic viseoelastic stresses, which helps to overcome the matrix and cause self-assembly.

Large amplitude oscillatory shear (LAOS)

Large amplitude oscillatory shear (LAOS) is most effective for particles that are 100 nm-1 µm in size.[8] Hard and soft shears can order in steady shear. However, this assembly strongly relies on particle volume fraction, particle interaction potentials, polydisterity, and shear rate and strain. The large amount of directing factors can cause complications in directing self-assembly by LAOS. Diblock copolymer micells have been studied in regard to structuring nanoparticles in bulk.

Combination of fields

The most effective self-assembly director is a combination of fields.[8] If the fields and conditions are optimized, self-assembly can be permanent and complete. When a field combination is used with nanoparticles that are tailored to be intrinsically responsive, the most complete assembly is observed. Combinations of fields allow the benefits of self-assembly, such as scalability and simplicity, to be maintained while being able to control orientation and structure formation. Field combinations possess the greatest potential for future directed self-assembly work.

Interfaces

Solid interfaces

Nano-particles can self-assemble on solid surfaces after applying external forces (like magnetic, electric, and flow) as mentioned in the above section. Templates made of microstructures like carbon nanotubes or block polymers can also be used to assist in self-assembly; they cause directed self-assembly (DSA) in which active sites are embedded to selectively induce nanoparticle deposition. Such templates are considered as any object onto which different particles can be arranged into a structure with a morphology similar to that of the template.[21] Carbon nanotubes (microstructures), single molecules, or block copolymers are common templates.[21] Nanoparticles are often shown to self-assemble within distances of nanometers and micrometers, but block copolymer templates can be used to form well-defined self-assemblies over macroscopic distances. By incorporating active sites to the surfaces of nanotubes and polymers, the functionalization of these templates can be transformed to favor self-assembly of specified nanoparticles.

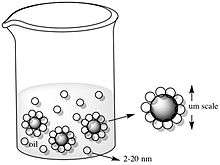

Liquid interfaces

Pickering and Ramsden explained the idea of pickering emulsions when experimenting with paraffin-water emulsions with solid particles like iron oxide and silicon dioxide. They observed that the micron-sized colloids generated a resistant film at the interface between the two immiscible phases, inhibiting the coalescence of the emulsion drops.[22] These Pickering emulsions, as shown in the figure below, are formed from the self-assembly of colloidal particles in two-part liquid systems, such as oil-water systems. The desorption energy, which is directly related to the stability of emulsions depends on the particle size, particle-particle interaction and, of course, particle-water and particle-oil interactions.[22]

A decrease in total free energy was observed to be a result from the assembly of nanoparticles at an oil/water (O/W) interface. This is shown in the following equation in which a particle with radius r at an interface between oil (O) and water (W) results in a decrease of the initial interfacial energy E0 to E1; this difference in energy is ΔE1.

At a fixed γP/O, γP/W, and γO/W, the equation shows that the stability of a particle assembly is determined by the radius square. When moving to the interface, particles reduce the unfavorable contact between the immiscible fluids and decrease the interfacial energy. The decrease in total free energy for microscopic particles is much larger than that of thermal energy; this results in an effective confinement of large colloids to the interface. They are irreversibly bound to the interface. Nanoscopic particles are restricted to the interface by an energy reduction comparable to thermal energy. Thus, nanoparticles are easily displaced from the interface. A constant particle exchange then occurs at the interface; the rate of this exchange depends on particle size. The thermally activated escape of small particles occurs more often than larger particles.[22] For the equilibrium state of assembly, the total gain in free energy is smaller for smaller particles. Thus, large nanoparticles assemblies are more stable. This size dependence allows nanoparticles to self-assemble at the interface to attain its equilibrium structure. Micrometer- size colloids, on the other hand, may be confined in a non-equilibrium state.

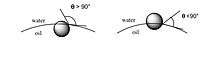

The interfacial tension and the wettability of a particle surface affect the desorption energy. The contact angle θ between the solid and the oil/water interface determines its wettability. As shown in the figure below, a contact angle θ greater than 90° favors a water-in-oil emersion while a contact angle θ less than 90° favors oil-in-water emulsion. These contact angles affect the stability of the emulsion.

A maximum desorption energy peak is observed at a contact angle of 90°. When the contact angle is greater than or less than this point, the desorption energy gradually decreases; thus, the stability of the emulsion decreases as well.

Applications

Material that consists with nano-particles is called "nanostructured material". The phase of "nanostructured material" implies two important ideas:

- that at least some of the heterogeneity in materials is determined by the size range of nanostructures (about 1–100 nm), and

- these nanostructures might be synthesized and distributed (or organized), at least in part.[23] The study of self-assembly nanoparticles is important to understand the interaction between single particle in terms of applying them into different applications.

Electronics

Self-assembly of nanoscale structures from functional nanoparticles has provided a powerful path to developing small and powerful electronic components. The difficulty of applied nanostructure material is nanoscale objects have always been difficult to manipulate because they cannot be characterized by molecular techniques and they are too small to observe optically. 2D self-assembly monodisperse particle colloids has a strong potential in dense magnetic storage media. Each colloid particle has the ability to store information as known as binary number 0 and 1 after applying it to a strong magnetic field. In the meantime, it requires a nanoscale sensor or detector in order to selectively choose the colloid particle.

Biological applications

Drug delivery

Block copolymers offer the ability to self-assemble into uniform, nanosized micelles[24][25] and accumulate in tumors via the enhanced permeability and retention effect.[26] Polymer composition can be chosen to control the micelle size and compatibility with the drug of choice. The challenges of this application are the difficulty of reproducing or controlling the size of self-assembly nano micelle, preparing predictable size-distribution, and the stability of the micelle with high drug load content.

Magnetic drug delivery

Magnetic nanochains are a class of new magnetoresponsive and superparamagnetic nanostructures with highly anisotropic shapes (chain-like) which can be manipulated using magnetic field and magnetic field gradient.[19] The magnetic nanochains possess attractive properties which are significant added value for many potential uses including magneto-mechanical actuation-associated nanomedicines in low and super-low frequency alternating magnetic field and magnetic drug delivery.

See also

References

- 1 2 Wetterskog, Erik; Agthe, Michael; Mayence, Arnaud; Grins, Jekabs; Wang, Dong; Rana, Subhasis; Ahniyaz, Anwar; Salazar-Alvarez, German; Bergström, Lennart (2014). "Precise control over shape and size of iron oxide nanocrystals suitable for assembly into ordered particle arrays". Science and Technology of Advanced Materials. 15 (5): 055010. Bibcode:2014STAdM..15e5010W. doi:10.1088/1468-6996/15/5/055010. PMC 5099683. PMID 27877722.

- ↑ Glotzer, S.C. (2004). "Some Assembly Required". Science. 306: 419–420. doi:10.1126/science.1099988.

- ↑ Boles, Michael A.; Engel, Michael; Talapin, Dmitri V. (2016). "Self-Assembly of Colloidal Nanocrystals: From Intricate Structures to Functional Materials". Chemical Reviews. 116 (18): 11220–11289. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00196.

- ↑ Hubler, A.; Osuagwu, O. (2010). "Digital quantum batteries: Energy and information storage in nanovacuum tube arrays". Complexity: NA. doi:10.1002/cplx.20306.

- ↑ Hubler, A.; Lyon, D. (2014). "Gap size dependence of the dielectric strength in nano vacuum gaps". IEEE. 20 (4): 1467. doi:10.1109/TDEI.2013.6571470.

- ↑ Shinn, E.; Hubler, A.; Lyon, D.; Grosse-Perdekamp, M.; Bezryadin, A.; Belkin, A. (2013). "Nuclear energy conversion with stacks of graphene nanocapacitors". Complexity. 18 (3): 24. Bibcode:2013Cmplx..18c..24S. doi:10.1002/cplx.21427.

- 1 2 3 4 5 O'Mahony, C.T.; Farell, R.A; Holmes, J.D.; Morris, M.A. (2011). "The thermodynamics of defect formation in self-assembled systems". Thermodynamics—Systems in Equilibrium and Non-Equilibrium: 279–306. doi:10.5772/20145. ISBN 978-953-307-283-8.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Grzelczak, Marek (2010). "Directed Self-Assembly of Nanoparticles". ACS Nano. 4 (7): 3591–3605. doi:10.1021/nn100869j.

- ↑ Boker, Alexander (2007). "Self Assembly of Nanoparticles at Interfaces". Soft Matter. 3 (10): 1231–1248. Bibcode:2007SMat....3.1231B. doi:10.1039/b706609k.

- ↑ http://www.nature.com/articles/natrevmats20168

- ↑ Kim, Jeong-Hwan. "Sequential Solid-Phase Fabrication of Bifunctional Anchors on Gold Nanoparticles for Controllable and Scalable Nanoscale Structure Assembly". Langmuir. 24: 5667–5671. doi:10.1021/la800506g.

- ↑ Kim, Jeong-Hwan. "Simultaneously Controlled Directionality and Valency on a Water-Soluble Gold Nanoparticle Precursor for Aqueous-Phase Anisotropic Self-Assembly". Langmuir. 26: 18634–18638. doi:10.1021/la104114f.

- ↑ Kim, Jin-Woo. "DNA-Linked Nanoparticle Building Blocks for Programmable Matter". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 50: 9185–9190. doi:10.1002/anie.201102342.

- ↑ http://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/6155226/

- ↑ http://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/5749842/

- 1 2 3 4 Faure, Bertrand; German Salazar-Alvarez; Lennart Bergstrom (2011). "Hamaker Constants of Iron Oxide Nanoparticles". Langmuir. 27 (14): 8659–8664. doi:10.1021/la201387d.

- 1 2 Pinchuck, Anatoliy (2012). "Size-Dependent Hamaker Constants for Silver Nanoparticles". Journal of Physical Chemistry. 116 (37): 20099–20102. doi:10.1021/jp3061784.

- 1 2 Subbaraman, Ram (2008). "Estimation of the Hamaker Coefficient for a Fuel-Cell Supported Catalyst System". Langmuir. 24 (15): 8245–8253. doi:10.1021/la800064a.

- 1 2 3 Kralj, Slavko; Makovec, Darko (27 October 2015). "Magnetic Assembly of Superparamagnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticle Clusters into Nanochains and Nanobundles". ACS Nano. 9 (10): 9700–9707. doi:10.1021/acsnano.5b02328.

- ↑ Grzelczak, Marek; Vermant, Jan; Furst, Eric M.; Liz-Marzán, Luis M. (2010-07-27). "Directed Self-Assembly of Nanoparticles". ACS Nano. 4 (7): 3591–3605. doi:10.1021/nn100869j. ISSN 1936-0851.

- 1 2 Grzelczak, S.; Vermant, J; Furst, E.M.; Liz-Marzan, L.M. (2010). "Directed Self-Assembly of Nanoparticles". ACS Nano. 4 (7): 3591–3605. doi:10.1021/nn100869j.

- 1 2 3 Boker, A.; He, J.; Emrick, T.; Russell, T.P. (2007). "Self-assembly of nanoparticles at interfaces". Soft Matter. 3 (10): 1231. Bibcode:2007SMat....3.1231B. doi:10.1039/b706609k.

- ↑ Whitesides, G.M.; Kriebel, J.K.; Mayers, B.T. (2005). "Self-Assembly and Nanostructured Materials" (PDF). Nanoscale Assembly – Chemical Techniques. Springer. doi:10.1007/b106927. ISBN 978-0-387-23608-7.

- ↑ Xiong, De'an; He, ZP (13 May 2008). "Temperature-responsive multilayered micelles formed from the complexation of PNIPAM-b-P4VP block-copolymer and PS-b-PAA core-shell micelles". Polymer. 49 (10): 2548–2552. doi:10.1016/j.polymer.2008.03.052.

- ↑ Xiong, De’an; Li, Zhe; Zou, Lu; He, Zhenping; Liu, Yang; An, Yingli; Ma, Rujiang; Shi, Linqi (2010). "Modulating the catalytic activity of Au/micelles by tunable hydrophilic channels". Journal of Colloid and Interface Science. 341 (2): 273–279. Bibcode:2010JCIS..341..273X. doi:10.1016/j.jcis.2009.09.045. ISSN 0021-9797.

- ↑ Radosz, Maciej; Zachary L. Tyrrell; Youqing Shen (Sep 2010). "Fabrication of micellar nanoparticles for drug delivery through the self-assembly of block copolymer". Progress in Polymer Science. 35 (9): 1128–1143. doi:10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2010.06.003.