San Agustín culture

The San Agustín culture is an archaeological culture present in modern-day Colombia. Several hundred monolithic sculptures have been found, dating from the 33rd century BCE to the 7th century BCE. There is an ongoing scientific study into its origins and nature. For its period, the culture displays considerable development in agriculture, ceramics, goldsmithing, and sculptural art.

The differences between objects, clothing, and sculptures have led archaeologists to hypothesize that the necropolis of San Agustín was a location where several South American ethnic groups from distant regions brought their important dead to be buried. This location is today the Parque Arqueológico Nacional de Tierradentro and the San Agustín Archaeological Park.

Geography

San Agustín is the name of a Columbian culture that dates back to the seventeenth century. This culture lived in a mountainous region in southern Colombia called the Andean mountains. The culture is situated in one of the bases of the Colombian Massif. Nearby, in the Páramo de las Papas, are some of the country's main river sources. These rivers cross the Colombian territory in different directions, having navigable flows for long distances. The Magdalena River is one of the most important routes, traveled since the Pleistocene era, and is where the European settlers who conquered the lands of the Muisca first arrived. El Cauca's largest tributary irrigates the fertile inter-Andean valleys, which are rich in gold veins, a land where quimbayas and other pre-Columbian goldsmiths sought a seat. The Caquetá leads to the Amazon after irrigating the jungle at the foot of the Andean mountains around which indigenous groups still live, some of them possible descendants of the old sculptors of San Agustín.

The geographical landscape consists of undulating hills and inclined planes that descend into narrow and deep canyons.

In the area of San Agustín, the rugged landscape creates a rapid succession of climates, from the cold of the Páramo de las Papas to the temperate areas in the slopes and canyons of the mountain range.

Archaeology

The area where the Pre-Columbian relics are located corresponds to the current municipalities of San Agustín, Isnos and Saladoblanco. Similar finds have also been identified near the slope that faces the Amazon, especially in the town of Santa Rosa del Caquetá. A vast amount of this area is still unexplored, particularly the areas that ascend to the Valley of the Popes, which is covered by dense jungle vegetation that only recently began to be dismantled by settlers. In this area, the nuclei of statues and tombs appear as ceremonial centers, isolated from each other. The historical tradition has bestowed these places with special names such as Mesitas, Lavapatas, Ullumbe, Alto de los Ídolos, Alto de las Piedras, Quinchana, El Tablón, La Chaquira, La Parada, Quebradillas, Sinks and others, which have mostly been preserved until today.

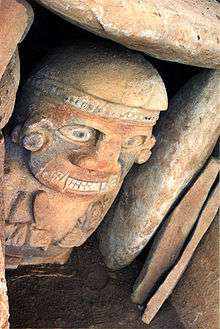

Concentrations of tombs have been found in such places. Some are lined with large slabs and monolithic sarcophagi inside, covered with artificial mounds that reach up to 30 m in diameter and 5 m in height. Others contain statues over 4 m in height and several tons in weight. The most outstanding lithic work is called "Fuente de Lavapatas", a rocky bed of the ravine of the same name, where the natives worked a fantastic ceremonial fountain with three pools and numerous serpentine and batracomorphic figures in low relief, surrounded by tiny channels through which water flows harmoniously. The site was dedicated to the worship of the aquatic deities and to the practice of healing ceremonies.

Discovery of the site and subsequent works

From the mid-sixteenth century (1536-1539) the southern region of the Andes of Colombia was crossed by Spanish expeditionaries, who founded populations that would soon have great significance in the colonizing process, such as Pasto, Popayán, Almaguer, Timaná and others. Sebastián de Belalcázar and García de Toledo advanced through the lands of the Macizo to reach the Alto Magdalena, precisely where San Agustín is located, before the first of them continued north to meet the hosts of Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada in the lands of the Muiscas, where Bogotá had just been founded. These expeditions were followed by others, who came into contact with indigenous groups that lived there and to which various documents that repose in the archives of Colombia and Spain refer. However, in none of these sources does any news related to the archaeological monuments of San Agustín appear, nor did the natives of the area reveal their existence to the newcomers. From the 18th century, when the destructive action of the treasure hunters began, the sculptural works that resided in the area became known.

The first information about the archaeological ruins of San Agustín appears in the work, Wonders of Nature, by the Mallorcan missionary Fray Juan de Santa Gertrudis, of the Observant Order, who visited the place several times in 1756. His travel chronicle, began in Cartagena de Indias and finished in Lima, remained unpublished in Palma de Mallorca for nearly two centuries, until in 1956 a copy of the manuscript was sent to Colombia and published in the same year.

Sculptor village

Archaeological research has reconstructed much of the culture of this settlement that inhabited the upper Magdalena. It is known today that it economically relied on farming corn, peanuts, chontaduro (Guilielma gasipaes), and cassava, in addition to complementary fishing and hunting activities. Evidence of such work has been verified in strata dating from the seventh century BCE. and that explain the fundamental features of his sculptural art, intimately related to the cosmogonic and religious conceptions. This contrasts markedly with the simple structure of their dwellings, which were circular in plan and covered with straw, a fact that is fully explained by Cieza de León (1518-1560), a chronicler of the Conquest.

The houses were built with decomposable materials, so little evidence of buildings has survived, except holes from round logs pushed into the ground. These logs formed walls and supported roofs, forming enclosures of three, five and even nine meters in diameter, were driven down, the larger apparently for the chiefs of the tribe or of the mohánes or shamans. A dwelling was usually made up of several huts, located in close proximity to one another. There they had bedrooms in the huts as well as stoves, which were made out of semi-rounded stones, on which they placed cooking vessels. They also used tripod pots with high and solid supports. There are traces of small workshops and waste dumps within or close to the houses.

The orography of the region, characterized by gentle undulations of volcanic origin, delimited by the course of numerous streams and streams, determined a pattern of dispersed settlement in the area of San Agustín, similar to that observed in the other regions of the region. it is Colombia today and it still persists in rural areas.

Culture (social organization)

The peculiar features that characterize the flourishing of the culture of San Agustín, between 300 CE to 800 CE, such as the great development of lithic statuary, which presents a stage well advanced from the seventh century BCE, the construction of large embankments or terraces for the location of the necropolis, the construction of retaining walls, the tombs covered with large stone slabs, some, the main ones, covered with artificial mounds crowned with funerary shrines, the ceremonial fountains carved in the living rock, they reflect an advanced organization of work and a social and political stratification. The sculpture, in particular, clearly indicates a true specialization of the work, since this activity, given the degree of complexity and advancement reached by its architects, supposes a great professional skill, a remarkable artistic talent and especially a deep knowledge of the religious beliefs of the tribe, through a long tradition of such religious manifestations. In addition, differences that can be seen in the structure of the tombs of the same site, without clear indications of a cultural sequence, speak more of a social stratification, since ceramics and other funerary items testify to the contemporaneity of one and the other. Such stratification would be based on the difference between the occupational groups and the political and religious hierarchy, consolidated in the formation of small lordships, a typical organization of most of the indigenous groups found by the Spaniards in the 16th century in the Andean region. from Colombia.

It is also possible to think that the great dispersion of lithic statuary in San Agustín is explained by the fact that there existed among these natives an organization structured on the basis of small family groups, linked together by religious ties. This same fact could clarify the reason for the great variety of motifs and styles represented in the statues within an apparent morphological homogeneity, diversity that would have obeyed the need to individualize in each place the representation of the protective deities of the family group, within the traditional religious canons. Shamanism or mohánismo would also play a significant role in this regard. Around these characters were grouped small family nuclei and those would have formed a kind of priestly caste, with marked influence on the social and political organization of a population that had a strong religious mentality, expressed in the rich theme that manifests itself in sculptural art. Everything suggests that in this flourishing period of Augustinian culture, social organization was strongly influenced by warrior groups and religious forms by solar deities and war. The statues of Mesitas A and B of the Archaeological Park seem to be the most authentic representation of this cultural moment. They appear guarding the entrance of tombs covered with large slabs, with monolithic sarcophagi inside, consecrated, surely, to guard the mortal remains of heroes of the tribe or their politico-military leaders.

Sculpture

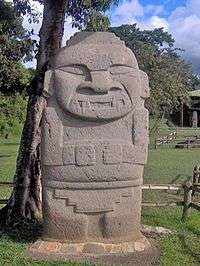

The peculiar manifestation of the culture of the ancient towns of San Agustín was the monumental lithic sculpture. More than 300 statues have been found, most of them in an area that appears fully delimited by the basins of the Magdalena, Bordones, Mazamorras and Sombrerillos rivers and the peaks of the Colombian Massif. Undoubtedly the natives wanted to make this region a true ceremonial center for funeral practices, presided over by the great monoliths, in which they expressed their symbolic style, without this purpose having prevented them from carving forms of great naturalism.

The blocks in which they were carved are volcanic tuffs and lava andesites, some of large dimensions, up to more than four meters high and several tons in weight. With the exception of the neighboring region of Tierradentro (Cauca) in no other area of Colombia are these monumental features of the sculpture and it can be stated, therefore, that they are confined to the Upper Magdalena.

The general structure of the archaeological complex of San Agustín offers some very characteristic features, such as the homogeneity of certain elements and their continuity through the different evolutionary periods, which speaks in favor of a cultural kinship of the different groups that concurred there and of a long tradition of them, expressed in indicative elements such as ceramics and lithic industry, as well as in certain motifs represented in the sculptures, whose ancestral forms began at least in the seventh century BCE and persist, next to later ones, until the 16th century CE.

As it happened in the formative period of the other cultures of the Andean zone and of Mesoamerica, the religious cults were in intimate relation with their main base of economic sustentation, agriculture, as well as with hunting and fishing. The fauna is very associated to its cosmogony; hence, in the sculptures appear several animals linked to a natural or productive phenomenon. The sun, moon, lightning, rain and other natural phenomena are personified and expressed in their symbols. The deities appear anthropo-zoomorphized and closely associated with the mortuary rites. The sun and the moon preside over its religious pantheon.

The frequency of representation of the feline mouth in most of the sculptures, is indicative of the cult of the jaguar, which seems to be one of the oldest and most widespread among the peoples that lived in the Andean area and that still persists in the populations aborigines who live in the Amazon jungle. In other Andean archaeological cultures this element also characterizes many of the sculptural representations.

The sculptures that are called caryatids, because they were destined to support the ceilings of the great tombs in Mesitas A and B of the archaeological park, are surely representations of warriors. Such is the case of the monoliths found in the northwest mound of Mesita B and in the eastern and western mounds of Mesita A. In these statues appears figuratively, in a naturalistic way, the image of warriors, adorned with special tiaras and carrying the weapons that they used (rounded stones, that they threw with the hand, shields or shields, that maintained with the left hand). In other statues the shield is replaced by a short club, the "macana" spoken by the chronicles of the 16th century, used by the panches, muzos, calimas and other groups, and which are still used by the chimilas, an indigenous people who live in the vicinity of the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta.

Personal dresses and ornaments

Many of the anthropomorphic figures that represent the statues, appear completely naked or only with light covers and with some ornaments, such as necklaces, bracelets, nose rings and earmuffs. This fact is curious, since the area of San Agustín is a region in which a moderately temperate climate predominates and this cools considerably as it ascends to the Valley of the Popes. Perhaps this allows to affirm that it is a town that had a prolonged stay in low lands before reaching the places where they worked their statues.

However, several sculptures have kilts and hats, the first made of cloth, the hats made of tree bark, as is customary in many tribes of the Amazon. Implements for spinning, such as spindle flywheels, are particularly rare in the record of the elements found in the archaeological excavations carried out. The ornaments were varied, such as necklaces of limestone and hard stone beads, these last ones of bluish green color, tubular, with longitudinal orifice; shell, seed, bone and gold beads; goldsmith's nosepieces, circular, laminated or in the manner of twisted wires, with horn or stone bead settings; solid gold earrings, figured in some tiny eagles; gold headbands, earmuffs and other ornaments that have been found in the excavations and that coincide in their shape with those observed in the statues.

Ceramics

The culture's ceramics are fundamentally monochromatic, made in an oxidizing atmosphere, by the winding system and with engobes of different ocher tones. Most of the items are small bowls, plates, tripod pots or high support cups. There are also large vessels, destined to the storage of liquids and to serve as funeral urns. The decoration is almost always incised, although negative painting is also registered, black on red, from the initial phases of the flourishing of culture, in the period called Superior Formative. In the final period, or Recent, bicolor positive painting appears, as well as a grainy decoration.

See also

Bibliography

- Duque Gómez, Luis. San Agustín. Delroisse, 1982.

- Fajardo, Julio José. San Agustín: una cultura alucinada. Barcelona, España, Plaza & Janés, 1977.

- Ramírez Sendoya, Pedro José. Jijon La cultura megalítica de San Agustín. 1958

- http://www.todacolombia.com/culturas-precolombinas-en-colombia/cultura-san-agustin.html

- https://www.colombia.com/colombia-info/historia-de-colombia/epoca-precolombina/san-agustin/