Russian conquest of Siberia

| Russian conquest of Siberia | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Yermak's Conquest of Siberia, a painting by Vasily Surikov | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Cossacks Allied Native Siberians |

Sibir Khanate (until 1598) Daurs Yakuts Chukchis | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

Kuchum Khan Daur prince Guigudar | ||||||

The Russian conquest of Siberia took place in the 16th and 17th centuries, when the Khanate of Sibir had become a loose political structure of vassalages that were being undermined by the activities of Russian explorers. Although outnumbered, the Russians pressured the various family-based tribes into changing their loyalties and establishing distant forts from which they conducted raids. To counter this, Kuchum Khan attempted to centralize his rule by imposing Islam on his subjects and reforming his tax-collecting apparatus.

Conquest of the Khanate of Sibir

The Russian conquest of Siberia began in July 1580 when some 540 Cossacks under Yermak Timofeyevich invaded the territory of the Voguls, subjects to Küçüm, the Khan of Siberia. They were accompanied by 300 Lithuanian and German slave laborers, whom the Stroganovs had purchased from the tsar. Throughout 1581, this force traversed the territory known as Yugra and subdued Vogul and Ostyak towns. At this time, they also captured a tax collector of Küçüm.

Following a series of Tatar raids in retaliation against the Russian advance, Yermak's forces prepared for a campaign to take Qashliq, the Siberian capital. The force embarked in May 1582. After a three-day battle on the banks of the river Irtysh, Yermak was victorious against a combined force of Küçüm Khan and six allied Tatar princes. On 29 June, the Cossack forces were attacked by the Tatars but again repelled them.

Throughout September 1582, the Khan gathered his forces for a defence of Qashliq. A horde of Siberian Tatars, Voguls and Ostyaks massed at Mount Chyuvash to defend against invading Cossacks. On 1 October, a Cossack attempt to storm the Tatar fort at Mount Chyuvash was held off. On 23 October, the Cossacks attempted to storm the Tatar fort at Mount Chyuvash for a fourth time when the Tatars counterattacked. More than a hundred Cossacks were killed, but their gunfire forced a Tatar retreat and allowed the capture of two Tatar cannons. The forces of the Khan retreated, and Yermak entered Qashliq on 26 October.

Küçüm Khan retreated into the steppes and over the next few years regrouped his forces. He suddenly attacked Yermak on 6 August 1584 in the dead of night and defeated most of his army. The details are disputed with Russian sources claiming Yermak was wounded and tried to escape by swimming across the Wagay River which is a tributary of the Irtysh River, but drowned under the weight of his own chainmail. The remains of Yermak's forces under the command of Mescheryak retreated from Qashliq, destroying the city as they left. In 1586 the Russians returned, and after subduing the Khanty and Mansi people through the use of their artillery they established a fortress at Tyumen close to the ruins of Qashliq. The Tatar tribes that were submissive to Küçüm Khan suffered from several attacks by the Russians between 1584–1595; however, Küçüm Khan would not be caught. Finally, in August 1598 Küçüm Khan was defeated at the Battle of Urmin near the river Ob. In the course of the fight the Siberian royal family were captured by the Russians. However, Küçüm Khan escaped yet again. The Russians took the family members of Küçüm Khan to Moscow and there they remained as hostages. The descendants of the khan's family became known as the Princes Sibirsky and the family is known to have survived until at least the late 19th century.

| Part of a series on |

| Cossacks |

|---|

|

| Cossack hosts |

| Other groups |

| History |

| Cossacks |

| Cossack terms |

Despite his personal escape, the capture of his family ended the political and military activities of Küçüm Khan and he retreated to the territories of the Nogay Horde in southern Siberia. He had been in contact with the tsar and had requested that a small region on the banks of the Irtysh River would be granted as his dominion. This was rejected by the tsar who proposed to Küçüm Khan that he come to Moscow and "comfort himself" in the service of the tsar. However, the old khan did not want to suffer from such contempt and preferred staying in his own lands to "comforting himself" in Moscow. Küçüm Khan then went to Bokhara and as an old man became blind, dying in exile with distant relatives sometime around 1605.

Conquest and exploration

In order to subjugate the natives and collect yasak (fur tribute), a series of winter outposts (zimovie) and forts (ostrogs) were built at the confluences of major rivers and streams and important portages. The first among these were Tyumen and Tobolsk — the former built in 1586 by Vasilii Sukin and Ivan Miasnoi, and the latter the following year by Danilo Chulkov.[2] Tobolsk would become the nerve center of the conquest.[3] To the north Beryozovo (1593) and Mangazeya (1600–01) were built to bring the Nenets under tribute, while to the east Surgut (1594) and Tara (1594) were established to protect Tobolsk and subdue the ruler of the Narym Ostiaks. Of these, Mangazeya was the most prominent, becoming a base for further exploration eastward.[4]

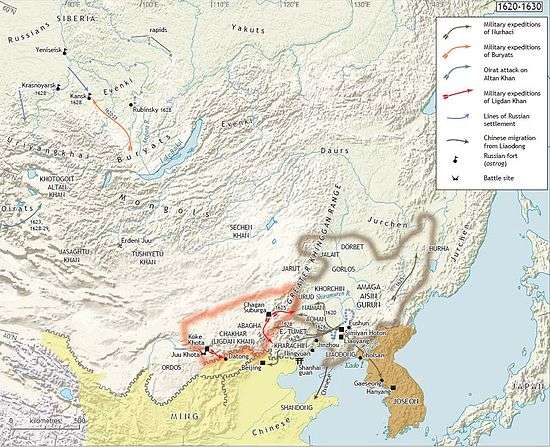

Advancing up the Ob and its tributaries, the ostrogs of Ketsk (1602) and Tomsk (1604) were built. Ketsk sluzhilye liudi ("servicemen") reached the Yenisei in 1605, descending it to the Sym; two years later Mangazeyan promyshlenniks and traders descended the Turukhan to its confluence with the Yenisei, where they established the zimovie Turukhansk. By 1610 men from Turukhansk had reached the mouth of the Yenisei and ascended it as far as the Sym, where they met rival tribute collectors from Ketsk. To ensure subjugation of the natives, the ostrogs of Yeniseysk (1619) and Krasnoyarsk (1628) were established.[4]

Following the khan's death and the dissolution of any organised Siberian resistance, the Russians advanced first towards Lake Baikal and then the Sea of Okhotsk and the Amur River. However, when they first reached the Chinese border they encountered people that were equipped with artillery pieces and here they halted.

The Russians reached the Pacific Ocean in 1639.[5] After the conquest of the Siberian Khanate (1598) the whole of northern Asia - an area much larger than the old khanate - became known as Siberia and by 1640 the eastern borders of Russia had expanded more than several million square kilometres. In a sense, the khanate lived on in the subsidiary title "Tsar of Siberia" which became part of the full imperial style of the Russian Autocrats.

The conquest of Siberia also resulted in the spread of diseases. Historian John F. Richards wrote: "... it is doubtful that the total early modern Siberian population exceeded 300,000 persons. ... New diseases weakened and demoralized the indigenous peoples of Siberia. The worst of these was smallpox "because of its swift spread, the high death rates, and the permanent disfigurement of survivors." ... In the 1650s, it moved east of the Yenisey, where it carried away up to 80 percent of the Tungus and Yakut populations. In the 1690s, smallpox epidemics reduced Yukagir numbers by an estimated 44 percent. The disease moved rapidly from group to group across Siberia."[6]

Indigenous population loss

Upon arrival in an area occupied by a tribe of natives, the Cossacks entered into peace talks with a proposal to submit to the White Tsar and to pay yasak, but these negotiations did not always lead to successful results. When their entreaties were rejected, the Cossacks elected to respond with force. At the hands of people such as Vasilii Poyarkov in 1645 and Yerofei Khabarov in 1650 some peoples, including the Daur, were slaughtered by the Russians. 8,000 out of a previous population of 20,000 in Kamchatka remained after being subjected to half a century by Cossacks.[7] The Daurs initially deserted their villages since they heard about the cruelty of the Russians the first time Khabarov came.[8] The second time he came, the Daurs decided to do battle against the Russians instead but were slaughtered by Russian guns.[9] In the 17th century, indigenous peoples of the Amur region were attacked by Russians who came to be known as "red-beards".[10]

In the 1640s the Yakuts were subjected to murderous expeditions during the Russian advance into the land near the Lena river, and on Kamchatka in the 1690s the Koryak, Kamchadals, and Chukchi were also subjected to this by the Russians according to Western historian Stephen Shenfield.[11] When the Russians did not obtain the demanded amount of yasak from the natives, the governor of Yakutsk, Piotr Golovin, who was a Cossack, used meat hooks to hang the native men. In the Lena basin, 70% of the Yakut population declined within 40 years, rape and enslavement were used against native women and children in order to force the natives to pay the Yasak.[8]

In Kamchatka the Russians savagely crushed the Itelmens uprisings against their rule in 1706, 1731, and 1741, the first time the Itelmen were armed with stone weapons and were badly unprepared and equipped but they used gunpowder weapons the second time. The Russians faced tougher resistance when from 1745-56 they tried to exterminate the gun and bow equipped Koraks until their victory. The Russian Cossacks also faced fierce resistance and were forced to give up when trying unsuccessfully to wipe out the Chukchi through genocide in 1729, 1730-1, and 1744-7.[12] After the Russian defeat in 1729 at Chukchi hands, the Russian commander Major Pavlutskiy was responsible for the Russian war against the Chukchi and the mass slaughters and enslavement of Chukchi women and children in 1730-31, but his cruelty only made the Chukchis fight more fiercely.[13] A genocide of the Chukchis and Koraks was ordered by Empress Elizabeth in 1742 to totally expel them from their native lands and erase their culture through war. The command was that the natives be "totally extirpated" with Pavlutskiy leading again in this war from 1744-47 in which he led to the Cossacks "with the help of Almighty God and to the good fortune of Her Imperial Highness", to slaughter the Chukchi men and enslave their women and children as booty. However the Chukchi ended this campaign and forced them to give up by killing Pavlitskiy and decapitating him.[14] The Russians were also launching wars and slaughters against the Koraks in 1744 and 1753-4. After the Russians tried to force the natives to convert to Christianity, the different native peoples like the Koraks, Chukchis, Itelmens, and Yukagirs all united to drive the Russians out of their land in the 1740s, culminating in the assault on Nizhnekamchatsk fort in 1746.[15] Kamchatka today is European in demographics and culture with only 2.5% of it being native, around 10,000 from a previous number of 150,000, due to the mass slaughters by the Cossacks after its annexation in 1697 of the Itelmen and Koryaks throughout the first decades of Russian rule. The killings by the Russian Cossacks devastated the native peoples of Kamchatka.[16] In addition to committing genocide the Cossacks also devastated the wildlife by slaughtering massive numbers of animals for fur.[17] 90% of the Kamchadals and half of the Vogules were killed from the eighteenth to nineteenth centuries and the rapid genocide of the indigenous population led to entire ethnic groups being entirely wiped out, with around 12 exterminated groups which could be named by Nikolai Iadrintsev as of 1882. Much of the slaughter was brought on by the fur trade.[18]

According to Western historian James Forsyth, Aleut men in the Aleutians were subjects to the Russians for the first 20 years of Russian rule, as they hunted for the Russians while Aleut women and children were hold as captives as a means to maintain this relationship.[19]

The oblastniki in the 19th century among the Russians in Siberia acknowledged that the natives were subjected to immense genocidal exploitation, and claimed that they would rectify the situation with their proposed regionalist policies.[20]

The Russian colonization of Siberia and conquest of its indigenous peoples has been compared to European colonization in the United States and its natives, with similar negative impacts on the natives and the appropriation of their land.[21] The Slavic Russians outnumber all of the native peoples in Siberia and its cities except in the Republic of Tuva, with the Slavic Russians making up the majority in the Buriat Republic, and Altai Republics, outnumbering the Buriat, and Altai natives. The Buriat make up only 29,51% of their own Republic, and the Altai only one-third; the Chukchi, Evenk, Khanti, Mansi, and Nenets are outnumbered by non-natives by 90% of the population. The natives were targeted by the tsars and Soviet policies to change their way of life, and ethnic Russians were given the natives' reindeer herds and wild game which were confiscated by the tsars and Soviets. The reindeer herds have been mismanaged to the point of extinction.[22]

The Ainu have emphasized that they were the natives of the Kuril islands and that the Japanese and Russians were both invaders.[23] In 2004, the small Ainu community living in Kamchatka Krai wrote a letter to Vladimir Putin, urging him to reconsider any move to award the Southern Kuril islands to Japan. In the letter they blamed both the Japanese, the Tsarist Russians and the Soviets for crimes against the Ainu such as killings and assimilation, and also urged him to recognize the Japanese genocide against the Ainu people, which was turned down by Putin.[24]

See also

References

- ↑ "Tlingit, Eskimo and Aleut armors." Archived 2014-02-22 at the Wayback Machine. Kunstamera. Accessed 10 Feb 2014.

- ↑ Lantzeff, George V., and Richard A. Pierce (1973). Eastward to Empire: Exploration and Conquest on the Russian Open Frontier, to 1750. Montreal: McGill-Queen's U.P.

- ↑ Lincoln, W. Bruce (2007). The Conquest of a Continent: Siberia and the Russians. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press.

- 1 2 Fisher, Raymond Henry (1943). The Russian Fur Trade, 1550-1700. University of California Press.

- ↑ 2008-03-31 Reference Nationalencyklopedin http://ne.se/jsp/search/article.jsp?i_art_id=715527

- ↑ Richards, 2003 p. 538.

- ↑ Bisher, Jamie (16 January 2006). "White Terror: Cossack Warlords of the Trans-Siberian". Routledge – via Google Books.

- 1 2 "The Amur's siren song". The Economist (From the print edition: Christmas Specials ed.). Dec 17, 2009. Retrieved 15 August 2014.

- ↑ Forsyth 1994, p. 104.

- ↑ Stephan 1996, p. 64.

- ↑ Levene 2005, p. 294.

- ↑ Black, Jeremy (1 October 2008). "War and the World: Military Power and the Fate of Continents, 1450-2000". Yale University Press – via Google Books.

- ↑ Forsyth 1994, pp. 145-6.

- ↑ Forsyth 1994, p. 146.

- ↑ Forsyth 1994, p. 147.

- ↑ "Yearbook" 1992, p. 46.

- ↑ Mote 1998, p. 44.

- ↑ Etkind 2013, p. 78.

- ↑ Forsyth 1994, p. 151.

- ↑ Wood 2011, pp. 89-90.

- ↑ Batalden 1997, p. 36.

- ↑ Batalden 1997, p. 37.

- ↑ McCarthy, Terry (September 22, 1992). "Ainu people lay ancient claim to Kurile Islands: The hunters and fishers who lost their land to the Russians and Japanese are gaining the confidence to demand their rights". The Independent.

- ↑ "Камчатское Время". kamtime.ru.

Further reading

- Bassin, Mark. "Inventing Siberia: visions of the Russian East in the early nineteenth century." American Historical Review 96.3 (1991): 763-794. online

- Batalden, Stephen K. (1997). The Newly Independent States of Eurasia: Handbook of Former Soviet Republics. Contributor Sandra L. Batalden (revised ed.). Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0897749405. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- Bisher, Jamie (2006). White Terror: Cossack Warlords of the Trans-Siberian. Routledge. ISBN 1135765952. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- Bisher, Jamie (2006). White Terror: Cossack Warlords of the Trans-Siberian. Routledge. ISBN 1135765960. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- Bobrick, Benson (December 15, 2002). "How the East Was Won". THE NEW YORK TIMES. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

- Black, Jeremy (2008). War and the World: Military Power and the Fate of Continents, 1450-2000. Yale University Press. ISBN 0300147694. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- Etkind, Alexander (2013). Internal Colonization: Russia's Imperial Experience. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0745673546. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- Forsyth, James (1994). A History of the Peoples of Siberia: Russia's North Asian Colony 1581-1990 (illustrated, reprint, revised ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521477719. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- Gibson, J. R. "The Significance of Siberia to Tsarist Russia," Canadian Slavonic Papers, 14 (1972): 442-53.

- KANG, HYEOKHWEON. Shiau, Jeffrey, ed. "Big Heads and Buddhist Demons:The Korean Military Revolution and Northern Expeditions of 1654 and 1658" (PDF). Emory Endeavors in World History (2013 ed.). 4: Transnational Encounters in Asia: 1–22. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Lantzeff, George Vjatcheslau, and Raymond Henry Fisher. Siberia in the seventeenth century: a study of the colonial administration (U of California Press, 1943).

- Lantzeff, G. V. and R. A. Pierce, Eastward to Empire: Exploration and Conquest on the Russian Open Frontier, to 1750 (Montreal, 1973)

- Levene, Mark (2005). Genocide in the Age of the Nation State: Volume 2: The Rise of the West and the Coming of Genocide. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 0857712896. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- Mote, Victor L. (1998). Siberia: worlds Apart. Westview series on the post-Soviet republics (illustrated ed.). Westview Press. ISBN 0813312981. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- Pesterev, V. (2015). Siberian frontier: the territory of fear. Royal Geographical Society (with IBG), London.

- Stephan, John J. (1996). The Russian Far East: A History (illustrated, reprint ed.). Stanford University Press. ISBN 0804727015. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- Wood, Alan (2011). Russia's Frozen Frontier: A History of Siberia and the Russian Far East 1581 - 1991 (illustrated ed.). A&C Black. ISBN 034097124X. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- Yearbook. Contributor International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs. International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs. 1992. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

Geography, topical maps

- Barnes, Ian. Restless Empire: A Historical Atlas of Russia (2015), copies of historic maps

- Catchpole, Brian. A Map History of Russia (Heinemann Educational Publishers, 1974), new topical maps.

- Channon, John, and Robert Hudson. The Penguin historical atlas of Russia (Viking, 1995), new topical maps.

- Chew, Allen F. An atlas of Russian history: eleven centuries of changing borders (Yale UP, 1970), new topical maps.

- Gilbert, Martin. Atlas of Russian history (Oxford UP, 1993), new topical maps.

- Parker, William Henry. An historical geography of Russia (Aldine, 1968).