Manuscripts of Dvůr Králové and Zelená Hora

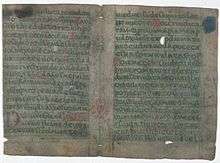

The Dvůr Králové and Zelená Hora manuscripts (Czech: Rukopis královédvorský, RK and Rukopis zelenohorský, RZ),[lower-alpha 1] also called the Queen's Court manuscript and Green mountain manuscript,[lower-alpha 2] are two purported medieval manuscripts of poetry in Old Czech which turned out to be literary hoaxes.

There were early suspicions about them, especially of the second manuscript by Josef Dobrovský and others, but the inauthenticity of both was not decisively established until 1886 in a series of articles in Tomáš Masaryk's Athenaeum magazine.

The two manuscripts

The first manuscript is abbreviated RK for short, after its Czech name Rukopis královédvorský, and the second is likewise abbreviated RZ;[lower-alpha 3] also RKZ stands collectively for both manuscripts.[1]

Queen's Court manuscript

The first, Dvůr Králové manuscript,[1] also called the "Queen's Court manuscript"[2][3] was claimed by Václav Hanka to have been discovered by him in 1817 in the Church of Saint John the Baptist at Dvůr Králové nad Labem (Queen's Court) in Bohemia.[2] The original texts written in Old Czech were published by Hanka in 1818, and a German version appeared the next year.[lower-alpha 4][2]

Green mountain manuscript

The latter, which eventually became known as the Zelená Hora manuscript[1] or "Green mountain manuscript"[2] was 1819, named after the Zelená Hora Castle it was purportely discovered in.

It had been mailed anonymously in 1818,p[lower-alpha 5] addressed to Franz, Count Kolowrat-Liebsteinsky,[lower-alpha 6] at the Bohemian Museum, the Count being Lord High Castellan (Oberst-Burggraf) of Prague, and backer of the newly founded museum.[4][5][6]

It was later uncovered that the sender was one Josef Kovář,[lower-alpha 7] who served as Rentmeister[lower-alpha 8] to Count Colloredo.[6] This Count was the owner of the Zelená Hora Castle ("Green Mountain Castle"[lower-alpha 9]),[7] and Kovář allegedly discovered the manuscript at this master's castle in Nepomuk in 1817.[8]

It was not until 1858–1859 that Kovář's role in this was publicly revealed, through research by Václav Vladivoj Tomek. Although Kovář had died by 1834, he found a Father Krolmus as witness.[9] And it was not until this time that the artefact referred as the Libušin soud manuscript (after the poem it contained) earned the name Rukopis zelenohorský or "Green mountain manuscript".[10][11]

Contents

Rukopis královédvorský, the first manuscript purportedly discovered, contained 14 poems: 6 epics, 2 lyric epics, and 8 love songs.[12] Záboj and Slavoj, two invented warrior-poets feature in the epics.

The Rukopis zelenohorský contained two poems, the "Sněmy" ("The Assemblies") and "Libušin soud" ("Lubuša's Verdict").[2]

Translations

A multilingual edition of the Rukopis Kralodvorský (with other poems) appeared in 1843, and to this was attached John Bowring's English translation.[13][lower-alpha 10]

Later, some of the poetry from the Queen's Court manuscript and "Lubuša's Verdict" ("Libussa's Judgment") were translated into English by Albert Henry Wratislaw and published in 1852.[lower-alpha 11][15][3]

Response

When the first manuscript appeared, the discovery was touted as a major coup. But when the second manuscript appeared, it was pronounced as a forgery by Josef Dobrovský, and Jernej Kopitar seconded the opinion, accusing Hanka of being the author of the hoax.[2][12][16] But many of the important Czech writers at the time supported the manuscripts' authenticity: dictionary compiler and author of a Czech literary history Josef Jungmann, writer Čelakovský, historian Palacký, poet-folklorist Erben.[12][2]

In England, John Bowring who became known as a translator of Slavonic poetry had dealings with both sides of the camp. When he first sought suitable Czech material, he approached Kopitar, who recommended Dobrovský to make a list. Later, Čelakovský learned of this enterprise, and not only furnished his own list, but became Bowring's close collaborator, sending him material with his German paraphrases for Bowring to work on.[17] Bowring (partly to make amends for the delayed publication of the Czech poetry anthology) wrote a piece in the Foreign Quarterly Review in 1828, which presented the case evenly for both sides.[lower-alpha 12][18]

A. H. Wratislaw noted in his 1852 translation that he was well aware of the controversy when he published his translation, but determined that the skeptics had not made their case.[19]

Alois Vojtěch Šembera wrote a book in 1879 which contended the "Libušin soud" poem (the second manuscript) to be a forgery, and named Josef Linda as its creator.[6]

The authenticity of both manuscripts was not rejected conclusively until the 1880s when several independently written articles appeared that assaulted their veracity.[20] This included Tomáš Masaryk taking the skeptic position,[20] and providing his journal Atheneum to publish a body of literature to support that view.[12][21][16] The linguist Jan Gebauer wrote an article debunking the manuscripts in the February 1886 issue,[22][5] and Masaryk in a later issue wrote that the poems could be proven as "reworked from Modern Czech to Old Czech", by looking for metrical or grammatical evidence.[23][24]

In the interim, the manuscripts were generally regarded romantically as evidence of early Czech literary achievement, with epic and lyric poetry predating even the Nibelungenlied. They were also interpreted as evidence that early Czech society had embraced democratic principles. Therefore, when the historian František Palacký (1798–1876) wrote his Czech history based partly on these manuscripts which he held to be facts, he depicted a romanticized Slav struggle against the German (non-democratic) social order.[1] Palacký's historical accounts of Bohemia based on the manuscripts also bolstered the Czechs' exclusive claims on Bohemia.

Pan-Slavic nationalists saw in the manuscripts a symbol of national conscience.

There was an ongoing struggle between the groups who insisted on their authenticity and those who pronounced them forgeries. The debate over the authenticity of these manuscripts has occupied Czech politics for more than a century, and voices claiming the poems to be genuine were not silenced even into World War II.[16]

Václav Hanka, the discoverer of the first manuscript, and his friend and roommate Josef Linda are generally regarded to have been the forgers of the poetry, but they never confessed to writing them, and there has not been any irrefuable proof they were the authors.[12]

See also

Explanatory notes

- ↑ Sometimes referred to collectively as RKZ

- ↑ German: Königinhofer Handschrift; Grünberger Handschrift.

- ↑ genitive case: RKho; RZho.

- ↑ German version was aided by Vaclav Alois Svobodá

- ↑ At any rate, it reached its destination in November 1818. Morfill in Westminster Review says it was sent in 1817.

- ↑ Also Anglicized as Count "Francis", in Czech, or "František" in Czech.

- ↑ German: Josef Kowář; also Joseph Kovar.

- ↑ Czech: důchodní.

- ↑ German: Schloss Grünberg

- ↑ Bowring seems to say in his foreword that he included "Lubuša's Verdict" ("Lubuśa's Judgment"), p. 281, but this seems to be wanting.

- ↑ There were two editions. The Prague edition of 1852 contained many typographical errors, compared with the 1852 Cambridge and London edition.[14]

- ↑ But it angered Kopitar that Hanka and Čelakovský (in Kopitar's estimation) should be treated as on par with the Dobrovský, the doyen on these matters.

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Rukopis královédvorský a zelenohorský. |

- Citations

- 1 2 3 4 Agnew, Hugh (2013), The Czechs and the Lands of the Bohemian Crown, Hoover Press (Stanford U.), p. 113

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Coleman, Arthur Prudden (1941), "John Bowring and the Poetry of the Slavs", Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, 84 (3): 450–451 JSTOR http://www.jstor.org/stable/984959

- 1 2 Morfill, William Richard (1890), An Essay on the Importance of the Study of the Slavonic Languages, Frowde, pp. 10–11

- ↑ Tomek (1859), pp. 14, 18–19.

- 1 2 Neubauer, John (2006), Lindberg-Wada, Gunilla, ed., "Rhetorical Uses of Folk Poetry in Nineteenth-Century East-Central Europe", Studying Transcultural Literary History, Walter de Gruyter, p. 91

- 1 2 3 Morfill (1879), p. 414.

- ↑ Tomek (1859), p. 19.

- ↑ Tomek (1859), pp. 4, 18–19.

- ↑ Ivanov, Miroslav (2000), Tajemství Rukopisů královédvorského a zelenohorského, Třebíč: Blok, p. 341 (in Czech)

- ↑

Ivanov, Miroslav (1969), Tajemství RKZ [Rukopisy Kralovédvorský a Zelenohorský], Prague: Mladi fronta, p. 223,

..na zámku Zelená Hora u Nepomuku, a proto se od Tomkovy doby Libušinu soudu říkalo Rukopis zelenohorský (..at the Zelená Hora castle near Nepomuk, and since Tomek's time, the "Lubuša's Verdict" [manuscript] has been called the Green Mountain Manuscript)

(in Czech) - ↑ Cf. Tomek (1859)

- 1 2 3 4 5 Hartwig (1999), p. 66.

- ↑ Hanka (ed.) & Bowring (tr.) (1843), pp. 274–316.

- ↑ Notes and Queries (1870), Series IV, 5, p. 556, "Bohemian Ballad-Literature" replied to by Wlatislaw on p. 605, "Queen's Court Manuscript"

- ↑ Wratislaw (tr.) (1852a) (Prague) and Wratislaw (tr.) (1852b) (Cambridge) editions.

- 1 2 3 Mark Jones, Mark Jones (1990), Fake?: The Art of Deception, University of California Press, pp. 68–69

- ↑ Coleman (1941), pp. 447–450.

- ↑ Coleman (1941), pp. 449–450.

- ↑ Wratislaw (tr.) (1852b), p. xiv.

- 1 2 Hartwig (1999), p. 66–67, citing Zacek (1984), p. 39, note 1

- ↑ Orzoff, Andrea (2009), Battle for the Castle: The Myth of Czechoslovakia in Europe, 1914-1948, Oxford University Press, p. 28 , citing Zeman, Zbyněk (1976), The Masaryks, pp. 47–48

- ↑ Gebauer, Jan (1886), "Potřeba dalších zkoušek Rukopisu Královédvorského a Zelenohorského" [The Need for Further Tests on the Dvůr Králové and Zelená Hora Manuscripts], Atheneum, III (5): 152–164 (in Czech)

- ↑ Masaryk, T. G. (1886), "Příspěvky k estetickému rozboru RKho a RZho" [Contributions to aesthetic analysis of RK and RZ], Atheneum, III (7): 298 (275–298)

- ↑ Jakobson, Roman (1988), Novák, Josef, ed., "Problems of Language in Masayk's Writings", On Masaryk: Texts in English and German, Rodopi, p. 71 ; citing Masaryk (1886), Atheneum III, p. 298

- Bibliography

- (primary sources)

- Hanka, Václav, ed. (1843), John Bowring, "Manuscript of the Queen's Court. A collection of old Bohemian lyrico-epic Songs, with other Ancient Bohemian Poems", Rukopis Kralodvorský: a jiné výtečnějšie národnie Spevopravné básné. Slovně i věrně vpróvodniem starém jazyku, o pripojeniem polského, Južno- Ruského, Illyrského, Kramkého, Horrolužického, Německého i Anglického Prěloženie, V Praze (Prague): Nákl. vydavetelovým, pp. 274–316

- Wratislaw, Albert Henry (tr.) (1852a), Manuscript of the Queen's Court: A Collection of Old Bohemian Lyrico-epic, Prague: Václav Hanka

- Wratislaw, Albert Henry (tr.) (1852b), The Queen's Court Manuscript, with Other Ancient Bohemian Poems, Cambridge: John Deighton

- (secondary sources)

- Hartwig, Kurt (1999), "The Incidental History of Folkore in Bohemia", The Folklore Historian, Indiana State University/Hoosier Folklore Society, 16, pp. 61–74

- Morfill, W. R. (1879), "The Bohemians and Slovaks", The Westminster Review, 56 (new ser.): 415–164

- Tomek, Václav Vladivoj (1859), Die Grünberger Handschrift. Zeugnisse über die Auffindung des "Libušin soud", Malý, Jakub Budislav (tr.) (in German)

External links

- Česká společnost rukopisná (Czech Manuscript Society) (2001). "The Manuscript of Dvůr Králové and The Manuscript of Zelená Hora". Archived from the original on 2016-03-06.