Royal Patriarchal Music Seminary of Lisbon

The Royal Patriarchal Music Seminary of Lisbon (Real Seminário de Música da Patriarcal de Lisboa) was founded by King John V (Portuguese: João) (hailed in history as "The Magnanimous" (Portuguese: O Magnánimo")) on 9 April 1713 to train singers for his Royal Chapel of Saint Thomas (Portuguese: capela de São Tomé) at Ribeira Palace (Portuguese: Paço da Ribeira). Its role was similar to that of other schools that had been training singers and musicians for other European cathedrals and royal chapels for some centuries. As its name suggests, the seminary was closely associated with both the court's life and the work of the Patriarch of Lisbon within the royal house.

Over time, its influence expanded as it produced singers, musicians and composers of international merit, many of whom took on careers in secular music including opera. It remained Portugal's most important music school until it was closed in 1834 and replaced the following year by the Lisbon National Conservatory (Portuguese: Conservatório Nacional de Lisboa).[1]

According to one analysis, "In it [the Seminary] was formed the great majority of our most outstanding eighteenth-century composers"[2], and the list drawn up by Fernandes includes Francisco António de Almeida, João Rodrigues Esteves, António Teixeira, José Joaquim dos Santos, António Leal Moreira and Marcos Portugal, among others.[3]

The Seminary and the Patriarchate of Lisbon

The creation of the Patriarchate

The Patriarchate of Lisbon came into being with papal approval following extensive pressure from John V. It was issued by Pope Clement XI on 7 November 1716 in the so-called "Golden Bull" In supremo apostolatus solio[4] by which the former archiepiscopal see of Lisbon was divided in two, the court's collegiate church was elevated to the role of cathedral for the see of Western Lisbon, and the episcopate was given a new title of patriarch with a leadership role within the wider church in Portugal and its empire. Also the patriarch continued as chaplain to the king and court.[5][6] This sublimation of the patriarch's role to the authority of the king was demonstrated by the co-relationship of the patriarchal throne within the king's court, the fact that the patriarch was also the king's chaplain, and by virtue of the way the king constructed the patriarchal residence as a wing of Ribeira Palace. As a member of the court, the patriarch was in a position both to be consulted by the king and required to obey his commands.[7]

Although the Seminary's foundation preceded the establishment of the Patriarchate of Lisbon by three years, once this new church structure was in place, the Seminary became an integral part of the patriarch's household. While its primary function, according to the king's own intention, was to train singers to perform within the court's liturgies provided by the patriarch, the Seminary's staff and students were seen as members of the patriarchal staff and its operating costs were met out of the patriarch's own budget.

Staff Structure

The staff structure and the names of staff and students from the Seminary's early period are largely unknown. Evidence shows that under the joint umbrella of the royal court and the Patriarchate, there were many more singers and musicians employed to provide liturgical and other music than those directly involved with the Seminary, and even within the Patriarchate itself, there was clear differentiation between the Seminary's teaching and the patriarchal music staff, even though they were all paid from the same budget. At the outset, it may well have been that the Seminary had a skeleton administrative staff, and the bulk of teaching was provided by choir masters, organists, composers and others who were on the court or patriarchal staff or who were employed elsewhere in Lisbon.

By the time the 1764 Statutes were issued, a more complex staff structure had appeared. It included the Inspector (Superintendent), the Reitor (Rector), the Vice Reitor (Vice Rector), the Mestres de Solfa (Masters of Solfège), the Mestres de Gramática (Masters of Grammar) ("who also taught rhetoric"), … the Sacristão (Sacristan), the Seminaristas (Seminarians),entre outros (among others, meaning housekeeping staff, servants, and even the tailor).[8] The Seminarians (Seminaristas) were included in this list because, as their primary purpose was to sing in the patriarch's liturgies, and they received income for this, they too were regarded as part of the patriarchal staff and the conditions of their engagement were spelt out in detail.[9]

Teaching environment

Syllabus influenced by Naples

The Seminary's syllabus was directly influenced by the four old music conservatories of Naples. Originally founded in the 17th century as charitable religious institutions for children who were homeless, abandoned or orphans, by the 18th century, these institutions had developed into proper music schools, with a combination of day and boarding students, and fees were often charged for attendance.[10][11]

Singing was a core subject right from the outset, as was composition for students who demonstrated skills in this area. The range of instruments being taught varied between different conservatories, but it was a standard requirement for all students to have basic keyboard skills, usually both harpsichord and organ because of these instruments' roles in accompaniment and continuo playing and as a fundamental to the Baroque ensemble. Singing teachers and choir masters taught solfège (Italian: solfeggio) as the sight-reading system. With the broad range of skills gained through these study programs, Naples' alumni were equally capable of being employed later in sacred and secular music.

At the height of their development, these conservatories had gained an international reputation, enhanced by producing some of Europe's celebrated composers and musicians, and this meant these institutions were able to draw students from many other European countries.[12]

Adaptation in Lisbon

Development of the Seminary's syllabus was governed by the fact that the training of singers for the Royal Chapel was its primary purpose. As in Naples, studying the harpsichord with its associated instrument, the clavichord, and the organ, and developing skills in the use of solfège (Portuguese: solfejo or solfa) were all compulsory, and every student received instruction in composition. The syllabus was more diverse, however, because the 1764 Statutes state that it is necessary for Seminarians to become "experts in Music, Grammar, Reading, Writing, and Organ" and for them to be educated in the "obligations of Catholics and in civil politics."[13]

The daily routine began between 5.30am and 6.30am, depending on the time of year, and ended at 10.00pm, alternating individual music lessons with class-based teaching, individual and class-based grammar lessons, instruction in religion, participation in Mass and the Divine Office, private penances and prayers, time for individual instrument practice, and assembly for meals.

Selection of students

The process and criteria by which students were selected in the Seminary's early years are not clear, but the standards as stated in the 1764 Statutes show that by that time students were required were required to have a “voz clara, suave e agudissima” (a clear, pleasant and high voice", a recognised baptismal certificate, and to come from parents of a respectable occupation. Most students were admitted at the age of 7 or 8 years although older boys could enter if they were already advanced in music studies.

Applicants were required to undertake an admission test which was administered by the rector, the solfège master and whoever else was selected to administer it. The majority lived in the boarding school although a small number of day boys (about 50 in 1761) were allowed to attend classes in the afternoon. As already stated, the names of early Seminarists are largely unknown, but from 1748 a detailed Book of Admissions was kept and this reveals much of the way in which criteria were applied to each applicant.[14]

Fernandes' calculations show that, "Of the 162 Seminarists included in the Book of Admissions, 107 were from Lisbon (the Ajuda parish was mostly in the 1780s and 1790s, which may be justified by the presence at this site of the Royal Chapel and the Patriarchal from 1792 ) and 37 from other areas. (...) the school was attended by five high school students from Óbidos, three from Miranda's bishopric, three from Caldas da Rainha, three from Setúbal and three from Peniche. Localities as diverse as Viseu, Lamego, Tavira, Miranda do Corvo, Barcelos, Leiria, Alcobaça, Elvas or Estremoz are represented by a single Seminarian."[15]

Training of castrati

By the reign of John V, castrati had already been performing in Italy and other European countries since the mid-16th century, and by the mid-18th century there were many on the opera stage and in the patriarchal choir. The first to arrive in Lisbon were members of the choir of St Peter's Basilica, Rome who came to Lisbon in 1716 coinciding with the elevation of the collegiate church to patriarchal status. There was great curiosity among the public and many approved of what they were hearing. At the same time, there were negative responses: a report about gossip regarding the price at which meat from the castrati (carne de castrato) would be sold led the king to say he would punish anyone who derided them.[16][17]

Evidence suggests that, as had happened in Italy, France and elsewhere, castration became a common practice when Portuguese parents, especially those of limited income, saw it as a way of ensuring their son's admission to a school or progression into a performing career.[18]

The date on which the first castrati were enrolled in the Seminary is unknown, but the 1764 Statutes say boys could be admitted if they were "castrated, with a soprano or alto voice". The Book of Admissions indicates that up to and including 1760, nine boys had already been castrated prior to entry[19], while for other boys who had already been accepted the notation says "to be castrated" (presumably prior to admission). For one who had already been admitted the notation says "For the surgeons to be castrated", and another another shows "for an opinion about castration." Two students, João Pirez [Pires] Neves[20] and Domingos Martins[21], were admitted on a written instruction from king Joseph I dated 3 September 1759 and to be castrated at the king's expense.

Some castrati went on to successful careers as singers, teachers and composers. But this was not always the case: as the Book of Admissions notes against one applicant who was already castrated, "he went out into the sacristy, he knew music and accompaniment," but he could not be trained in "singing for being out of tune."

Composers and musicians study in Italy

The first three Portuguese funded for further training in Rome, all Seminary alumni, departed during the first half of the 18th century: António Teixeira who went in 1714 and returned to Lisbon in 1728 where he was a chaplain-singer at Lisbon Cathedral and examiner of plainchant for the patriarchy; João Rodrigues Esteves who began studies with composer Giuseppe Ottavio Pitoni in 1719 before returning to Lisbon in 1726 where he became master of music at Lisbon Cathedral three years later; and Francisco António de Almeida who was in Rome from 1722 and returned 1726 to become organist at the Royal Chapel.[22]

Later, a second bout received funding to study in Naples. These included: João de Sousa Carvalho, an alumnus of the Braganza ducal palace's Colégio dos Santos Reis at Vila Viçosa who went in 1761 and returned six years later where he taught counterpoint at the Seminary, composed and held other major positions, brothers Jerónimo Francisco de Lima and Bras Francisco de Lima, Joaquim de Santa Anna, Camilo [Camillo] Jorge Dias Cabral and José [Joze] de Almeida [Almeyda].[23]

Marcos Portugal was organist and composer at the Patriarchate before receiving financial assistance, probably from Prince Regent John, to study in Italy. He was there from 1792 to 1800, and having established a good reputation as an opera composer, he returned to Lisbon to become music director of the newly-built opera house, the Teatro Real de São Carlos. Many of his own operas were staged there.

Seminary's continuation

Under new monarchs

John V died on 31 July 1750 and the Seminary continued its work through the next three monarchs, Joseph I (Portuguese: José), Maria I, and John VI who was Prince Regent after his mother Maria had been declared insane[24] and succeeded her as king after her death.

French invasion

Portugal's monarchy was driven into exile in Brazil by theFrench invasion which began in 1807 and climaxed with the fall of Lisbon the following year. The royal family's departure in 1808 was a major blow for the Seminary and between then and the monarch's return in 1821 there were no enrollments.

Seminary's closure

The next major crisis was the Portuguese Civil War which began in 1828 and ended in 1834. This led, among other things, to the secularisation of the education system,[25] the Seminary's closure, and as initiated by Almeida Garrett and an Seminary alumnus, João Domingos Bomtempo, the opening of the new National Conservatory of Music the following year.[26]

Alumni - Selective list

- Almeida, Francisco António de (c. 1702–c. 1755?)

- Almeida, José de (c.1738–?) Accessed 27 September 2018.

- Bomtempo, João Domingos (1775–1842)

- Cabral, Camillo Jorge Dias (c. 1749–c. 1805) Accessed 27 September 2018.

- Gomes, André da Silva (1752–1844) Accessed 27 September 2018.

- Esteves, João Rodrigues (c. 1700–c. 1751)

- Louzado, Vicente Miguel (c. 1750–1831) Accessed 27 September 2018.

- Martins, Domingos (c. 1747/48–?) Accessed 27 September 2018.

- Mattias, José (c. 1750/5 –?) Accessed 27 September 2018.

- Mazziotti, João Paulo (Giovanni) (1786?–1850) Accessed 27 September 2018.

- Mixelim, Joaquim do Vale (Mexelim according to Brito[27])

- Mosca, José Alves (Álvares) (c. 1750/51–?) Accessed 27 September 2018.

- Mosca, Manoel Alves [Álvares] (1747/48–1818) Accessed 27 September 2018.

- Neves, Joaõ Pirez [Pires] (Miranda, c. 1733–?) Accessed 27 September 2018.

- Oliveira, Joaquim de (1748-49–after 1806) Accessed 27 September 2018.

- Oliveira, Jozé Rodrigues de (c. 1740–1806) Accessed 27 September 2018.

- Portugal [Portogallo], Marcos [Marco] António (da Fonseca) (1762–1830) Accessed 27 September 2018.

- Portugal, Simão (1774–1845)[28]

- Rego, António José do (fl. 1783–182?)[29]

- Santos, José Joaquim dos (1747?–1801)

- Seixas, José António Carlos de (1704–1742)

- Teixeira, António (1707–1774)

References

- ↑ Following a reform of the old Lisbon Conservatory in 1982 several new music training schools were created including the Lisbon College of Music (Portuguese: Escola Superior de Música de Lisboa) which is associated with the Lisbon Polytechnic Institute (Portuguese: Instituto Politécnico de Lisboa). Accessed 3 August 2018.

- ↑ Cymbron, Luísa and Manuel Carlos Brito. História da Música Portuguesa (History of Portuguese Music). Universidade Aberta, 1992. p. 105. ISBN 978-972-674-086-5.

- ↑ Fernandes, Cristina. Boa voz de tiple, sciencia de música e prendas de acompanhamento. O Real Seminário da Patriarcal (1713-1834) (Good treble voice, music science and accompanying gifts. The Royal Seminary of the Patriarchal (1713-1834)). Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal, 2013. p. 9. Accessed 7 August 2018.

- ↑ In a summary of the pope's intention, Clemente gives three reasons: 1) D. John V piously corresponded to the papal request, well in keeping with the traditional zeal of the Portuguese kings in defending and propagating the faith, and even sent a navy to combat the Turks. 2) D. João V manifested the desire to have in his palace a cathedral, elevating to this condition the collegiate of São Tomé. 3) To this end, the Pope divided in two the archdiocese of Lisbon, hosting one in the royal chapel and the other where it was, divided to east and west from the "oldest walls of the city." (See Clemente, Manuel José Macário do Nascimento. Notas históricas sobre o Tricentenário do Patriarcado de Lisboa (Historical notes on the Tercentenary of the Patriarchate of Lisbon). Patriarcado de Lisboa, 2016. par. 7. Accessed 6 August 2018.)

- ↑ Again, to explain the pope's reason behind this arrangement, Clemente quotes directly from the Bull: ""Finally, considering that the said metropolitan church of western Lisbon, which we have erected and instituted by the present letters, exists in the royal palace of Lisbon, and in it many times the royal people may be present to the ecclesiastical functions, we deem it very convenient that the same metropolitan church of western Lisbon and the one who at all times is archbishop of western Lisbon be awarded with greater pardons, privileges and prerogatives by special indulgence of ours and of the Apostolic See." (See "Notas históricas…", par. 7.)

- ↑ 18th century German Protestant geographer, historian, educator and theologian Anton Friedrich Büsching noted that the patriarch was also known as Capelão-mor (or First Court Chaplain). (See Büsching, Anton Friedrich. A New System of Geography: In which is Given, a General Account of the Situation and Limits, the Manners, History, and Constitution, of the Several Kingdoms and States of the Known World, Vol. 2. A. Millar in the Strand., 1762. p. 180.

- ↑ While the Patriarchate continued to exist, Pope Benedict XIV judged the existence of two metropolitical archdioceses in one city as clumsy and unnecessary and on 13 December 1740 reunited them, returning Lisbon Cathedral to its role as the archiepiscopal seat for the patriarch.

- ↑ Estatutos do Real Seminario, ch. 2, no. 3, pp. 2–37.

- ↑ Christovam, Ozório and Diósnio Neto. A relação musical entre Lisboa e Nápoles durante o século XVIII (The musical relationship between Lisbon and Naples during the 18th century). (2013). Conference paper from II Jornada Discente do Programa de Pós Graduação em Música da ECA-USP, 2013. p. 5. Accessed 14 August 2018.

- ↑ In Italian, the word conservati had been used as meaning 'an orphan'; hence its expansion into conservatorio as a place where care was provided, and was later adapted into common use regarding a tertiary music school as a conservatorium or conservatoire. (See Encyclopedia Britannica "Conservatory". Accessed 28 August 2018.)

- ↑ For a more complete history, see Cafiero, Rosa. "Conservatories and the Neapolitan School: a European model by the end of the 18th century?" Music Education in Europe (1770-1914): Compositional, Institutional and Political Challenges, Vol. I, edited by Michael Fend and Michel Noiray. BWV Berlin Wissenschafts-Verlag, 2005. pp. 15-29. Accessed 28 August 2018.

- ↑ The conservatories were finally consolidated in 1826 to become the Conservatorio di Musica San Pietro a Majella (English: San Pietro a Majella Music Conservatory) which still exists."Conservatorio di Musica San Pietro a Majella." Accessed 28 August 2018.

- ↑ Estatutos do Real Seminario, ch. 2, no. 3, p. 5.

- ↑ Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal. Real Seminario da Patriarcal (Lisboa), Livro que hade servir p[ar]a os acentos das adimiçoins dos Siminaristas deste Real Siminario na forma dos seus Estatutos 1748-1820 (Royal Seminary of the Patriarchal (Lisbon), a book that will record an account of Seminarians' admission to this Royal Seminary according to its Statutes 1748-1820). Accessed 8 August 2018.

- ↑ Fernandes, Boa voz de tiple …, p. 50.

- ↑ Fernandes, Também houve castrati portugueses (There were also Portuguese castrati) Accessed 10 August 2018.

- ↑ Martinho, Bruno A. "O Paço da Ribeira nas Vésperas do Terramoto". Master dissertation in History of Art, Universidade Nova de Lisboa, 2009. Accessed 7 August 2018.

- ↑ Fernandes coordinates the development of castration in Portugal with the reign of John V (SFernandes, Também houve castrati portugueses, par. 4.), however Ginsberg and Leruth say, "They had existed in Portugal and Spain for centuries but they had not been considered as substitutes for male or female singers. In Italy, on the other hand, they quickly became fashionable and a large number of them (“by the thousands,” according to Haböck, 1927, p. 150) arrived from Spain and Portugal in the second half of the 16th century." (Ginsburgh, Victor and Luc Leruth. The Rise and Fall of Castrati. ECARES Working Papers, ECARES 2017-15, Universite Libre de Bruxelles. Accessed 14 October 2018.) Still referring to the 16th century, Ginsberg and Leruth say that because of high demand, the cost to the church of paying for boys to be castrated became prohibitively high and "Determined to further increase the supply of potential singers, the Church decided to offer to any boy who had suffered an “unfortunate accident” (that is, a castration) a guaranteed minimum standard of living in the form of basic food and lodging, together with musical training. This offer was hard to resist for Spanish or Portuguese families and many decided to sacrifice the boyhood of one or several of their sons." (p. 7.)

- ↑ Camilo [Camillo] Jorge Dias Cabral, Domingos Martins, João Pirez [Pires) Neves, Joze [José] de Oliveira, Joze [José] Alvez, Joze [José] de Almeida [Almeyda], Joze [José] Rodrigues de Oliveira, Manoel Alves and José Mattias.

- ↑ Neves was aged 27, probably the oldest student ever taken in, is described as being being "clérigo in minoribus" (clergy in minor orders or in a rank lower than subdeacon), and once he had gained music knowledge he would join the patriarchal choir and receive a wage according to his merit. His voice was in the alto range.() Accessed 14 October 2018.

- ↑ Accessed 14 October 2018.

- ↑ Another, not a Seminary alumnus, was composer and violinist Romão Mazza who in 1733 at the age of 14 was funded by Queen Maria Anna to study in Naples.

- ↑ Fernandes, Boa voz de tiple …, p. 12.

- ↑ Peters, Timothy, and Clive Willis. "Maria I of Portugal: Another royal psychiatric patient of Francis Willis." British Journal of Psychiatry, Vol. 203/3, September 2013. p. 167. Accessed 25 September 2018.

- ↑ A government decree issued on 21 January 1834 set up enrolment as available to all members of the public and free of charge to anyone who wished to attend. (See Ribeiro, p. 71.

- ↑ Fernandes, "Houve uma escola de música…"

- ↑ Brito, Manuel Carlos de. Opera in Portugal in the Eighteenth Century. Cambridge University Press, 1989. p. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-521-35312-0.

- ↑ Harper, p. 23.

- ↑ Harper, p. 23.

Bibliography

The Court, the Patriarch and the Seminary

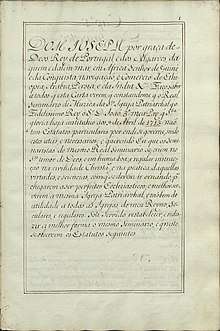

- Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal. Estatutos do Real Seminario da S[ant]a Igreja Patriarchal. - Ajuda 23 de Agosto de 1764 (Statutes of the Royal Seminary of the Patriarchal Church. - Ajuda 23 August 1764). Accessed 8 August 2018.

- –––. Real Seminario da Patriarcal (Lisboa), Livro que hade servir p[ar]a os acentos das adimiçoins dos Siminaristas deste Real Siminario na forma dos seus Estatutos 1748-1820 (Royal Seminary of the Patriarchal (Lisbon), a book that will record an account of Seminarians' admission to this Royal Seminary according to its Statutes 1748-1820). Accessed 8 August 2018.

- "Dicionário Biográfico Caravelas" (Caravelas Biographical Dictionary). Edited by David Cranmer and others. Caravelas – Núcleo de Estudos da Historia da Música Luso-Brasileira (Caravelas - Center for Studies on the History of Luso-Brazilian Music). Centro de Estudos de Sociologia e Estética Musical (Centre for the Study of the Sociology and Aesthetics of Music) (CESEM). Accessed 27 September 2018. ISBN 989-97732-2-0.

- Clemente, Manuel José Macário do Nascimento. Notas históricas sobre o Tricentenário do Patriarcado de Lisboa (Historical notes on the Tercentenary of the Patriarchate of Lisbon). Patriarcado de Lisboa, 2016. Accessed 6 August 2018.

- –––. No Curso dos Tempos (In the Course of Time). Patriarcado de Lisboa, 2016. Accessed 9 August 2018.

- d'Alvarenga, João Pedro. "‘To make of Lisbon a new Rome': The repertory of the Patriarchal Church in the 1720s and 1730s." Cambridge University Press: Eighteenth Century Music, Vol. 8/2, September 2011. pp. 179–214. Published online 25 July 2011. Accessed 29 September 2018.

- Fernandes, Cristina. "As Práticas Devocionais Luso-brasileiras no Final do Antigo Regime: o Repertório Musical das Novenas, Trezenas e Setenários na Capela Real e Patriarcal de Lisboa" (The Luso-Brazilian Devotional Practices at the End of the Old Regime: The Musical Repertoire of Novenas, Trezenas and Setenários in the Royal and Patriarchal Chapel of Lisbon). Revista Música Hodie, Vol. 14/2, 2014. pp. 213–231. Accessed 28 September 2018. ISSN 1676-3939.

- –––. Boa voz de tiple, sciencia de música e prendas de acompanhamento. O Real Seminário da Patriarcal (1713-1834) (Good tiple voice, music science and accompanying gifts. The Royal Seminary of the Patriarchal (1713-1834)). Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal, 2013. Accessed 7 August 2018.

- –––. Houve uma escola de música onde hoje está o Museu de História Natural (There was a music school in what is now the Natural History Museum). Accessed 5 August 2018.

- Peters, Timothy, and Clive Willis. "Maria I of Portugal: Another royal psychiatric patient of Francis Willis." British Journal of Psychiatry, Vol. 203/3, September 2013. p. 167. Accessed 25 September 2018.

- Ribeiro, Ana Isabel. “The Use of Religion in the Ceremonies and Rituals of Political Power (Portugal, 16th to 18th Centuries)." Religion, Ritual and mythology. Aspects of Identity Formation in Europe, edited by Joaquim Ramos de Carvalho. Pisa University Press, 2006. pp. 265–274. Accessed 18 August 2018.

Portuguese Music

- Augustin, Kristina. "A trajetória dos castrati nos teatros da corte de Lisboa (séc. XVIII)" (The trajectory of the castrati in the court theaters of Lisbon (18th century)). Revista Música e Linguagem. Vol 1/3 (2013), pp. 73–94.

- Brito, Manuel Carlos de. Opera in Portugal in the Eighteenth Century. Cambridge University Press, 1989. ISBN 978-0-521-35312-0.

- –––. "Portugal and Brazil." The Cambridge Companion to Eighteenth-Century Opera. Edited by Anthony R. DelDonna and Pierpaolo Polzonetti. Cambridge University Press, 2009. pp. 233–243. ISBN 978-0-521-69538-1.

- Christovam, Ozório and Diósnio Neto. A relação musical entre Lisboa e Nápoles durante o século XVIII (The musical relationship between Lisbon and Naples during the 18th century). (2013). Conference paper from II Jornada Discente do Programa de Pós Graduação em Música da ECA-USP, 2013. Accessed 14 August 2018.

- de Alegria, Cónego José Augusto. "História da Capela e Colégio dos Santos Reis de Vila Viçosa" (History of the Chapel and School of the Epiphany at Vila Viçosa). Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, 1983. ISBN 972-666-015-7.

- Dottori, Maurício. The Church Music of Davide Perez and Niccolò Jommelli. DeArtes – UFPR, 2014. p. 67. ISBN 978-85-98826-19-6.

- Fernandes, Cristina. Também houve castrati portugueses (There were also Portuguese castrati). Accessed 10 August 2018.

- Rees, Owen. “The History of Music in Portugal.” Early Music, Vol. 24/3, 1996. pp. 500–503. JSTOR, Accessed 6 August 2018.)

- Stevenson, Robert. "Lisbon: I. To 1870." The Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, edited by Stanley Sadie. Macmillan Publishing, 1980. Vol. 11, pp. 24–25. ISBN 0-333-23111-2.

- –––. "Portugal: I. Art Music." The Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, edited by Stanley Sadie. Macmillan Publishing, 1980. Vol. 15, pp. 139–141. ISBN 0-333-23111-2.

- Vasconcellos, Joaquim de. Os músicos portuguezes: biographia - bibliographia (The Portuguese musicians: Biographia - bibliographia). Vol. 1, Imprensa portugueza, 1870. Accessed 20 September 2018.

- –––. Os músicos portuguezes: biographia - bibliographia (The Portuguese musicians: Biographia - bibliographia). Vol. 2, Imprensa portugueza, 1870. Accessed 19 September 2018.

- Vieira, Ernesto. Diccionario biographico de músicos portuguezes: historia e bibliographia da música em Portugal (Biographical Dictionary of Portuguese Musicians: History and Bibliography of Music in Portugal). Vol. 1. Mattos Moreiro & Pinheiro, 1900. Accessed 10 September 2018.

- –––. Diccionario biographico de músicos portuguezes: historia e bibliographia da música em Portugal (Biographical Dictionary of Portuguese Musicians: History and Bibliography of Music in Portugal). Vol. 2. Mattos Moreira & Pinheiro, 1900. Accessed 10 September 2018.

- Vilão, Rui César. History of the Portuguese music: An overview. 20 August–2 September 2000. European School of High-Energy Physics (CERN) and the University of Coimbra, 2001. pp. 277–286. DOI = 10.5170/CERN-2001-003.277. Accessed 26 September 2018.

Music in general

- Buelow, George J. A History of Baroque Music. Indiana University Press, 2004.

- Cafiero, Rosa. "Conservatories and the Neapolitan School: a European model by the end of the 18th century?" Music Education in Europe (1770-1914): Compositional, Institutional and Political Challenges, Vol. I, edited by Michael Fend and Michel Noiray. BWV Berlin Wisenschafts-Verlag, 2005. pp. 15–29. Accessed 28 August 2018.

- Benedetto, Renato di. "Naples: 4. 17th and 18th Centuries: The Neapolitan School." The Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, edited by Stanley Sadie. Macmillan Publishing, 1980. Vol. 13, pp. 24–29. ISBN 0-333-23111-2.

History, society and culture

- Andrade, António Alberto Banha de. Vernei e a cultura do seu tempo (Vernei and the culture of our time). Imprensa de Coimbra, 1965. Accessed 28 September 2018.

- Fernandes, Lidia, Rita Fragoso and Carlos Cabral Loureiro. "Entre o Teatro Romano e a Sé de Lisboa: evolução urbanística e marcos arquitectönicos da antiguidade à reconstrução pombalina" (Between the Roman Theater and the Lisbon Cathedral: urban evolution and architectural landmarks from antiquity to the reconstruction of Pombal). Estudos de Lisboa, No. 11, edited by Pedro Flor. Instituto de História da Arte, Faculdade de Ciências Sociais e Humanas, Universidade Nova de Lisboa, 2014. pp. 27–29. Accessed 30 August 2018.

- Livermore, Harold Victor. A new history of Portugal. 2nd ed., Cambridge University Press, 1969. ISBN 0-521-09571-9

- Martinho, Bruno A. O Paço da Ribeira nas Vésperas do Terramoto. Master dissertation in History of Art, Universidade Nova de Lisboa, 2009. Accessed 7 August 2018.

- Ribeiro, José Silvestre. História dos estabelecimentos scientificos litterarios e artisticos de Portugal nos successivos reinados da monarchia (History of scientific, literary and artistic establishments of Portugal in the successive reigns of monarchs). Vol. 6. Academia real das sciencias, 1876. Accessed 1 September 2018.