Roxan (protein)

| ZC3H7B | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Aliases | ZC3H7B, RoXaN, zinc finger CCCH-type containing 7B | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| External IDs | MGI: 1328310 HomoloGene: 9735 GeneCards: ZC3H7B | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Orthologs | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Species | Human | Mouse | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Entrez | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ensembl | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| UniProt | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| RefSeq (mRNA) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| RefSeq (protein) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

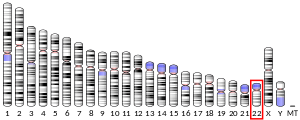

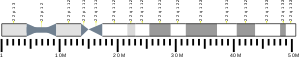

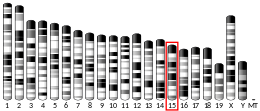

| Location (UCSC) | Chr 22: 41.3 – 41.36 Mb | Chr 15: 81.75 – 81.8 Mb | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| PubMed search | [3] | [4] | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Wikidata | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

RoXaN (Rotavirus 'X'-associated non-structural protein) also known as ZC3H7B (zinc finger CCCH-type containing 7B), is a protein that in humans is encoded by the ZC3H7B gene.[5] RoXaN is a protein that contains tetratricopeptide repeat and leucine-aspartate repeat as well as zinc finger domains. This protein also interacts with the rotavirus non-structural protein NSP3.[5]

Function

Rotavirus mRNAs are capped but not polyadenylated, and viral proteins are translated by the cellular translation machinery. This is accomplished through the action of the viral Nonstructural Protein NSP3 which specifically binds the 3' consensus sequence of viral mRNAs and interacts with the eukaryotic translation initiation factor eIF4G I.[6]

RoXaN (rotavirus X protein associated with NSP3) is 110-kDa cellular protein that contains a minimum of three regions predicted to be involved in protein–protein or nucleic acid–protein interactions. A tetratricopeptide repeat region, a protein–protein interaction domain most often found in multiprotein complexes, is present in the amino-terminal region. In the carboxy terminus, at least five zinc finger motifs are observed, further suggesting the capacity of RoXaN to bind other proteins or nucleic acids. Between these two regions exists a paxillin leucine-aspartate repeat (LD) motif which is involved in protein–protein interactions.[6]

Clinical significance

RoXaN is capable of interacting with NSP3 in vivo and during rotavirus infection. Domains of interaction correspond to the dimerization domain of NSP3 (amino acids 163 to 237) and the LD domain of RoXaN (amino acids 244 to 341). The interaction between NSP3 and RoXaN does not impair the interaction between NSP3 and eIF4G I, and a ternary complex made of NSP3, RoXaN, and eIF4G I can be detected in rotavirus-infected cells, implicating RoXaN in translation regulation.[6]

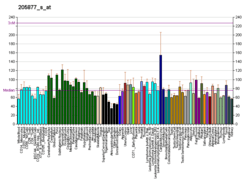

Expression of RoXaN was found to be correlated with a higher tumor grad in GIST (gastrointestinal stromal tumors).[7]

References

- 1 2 3 GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000100403 - Ensembl, May 2017

- 1 2 3 GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000022390 - Ensembl, May 2017

- ↑ "Human PubMed Reference:".

- ↑ "Mouse PubMed Reference:".

- 1 2 "Entrez Gene: ZC3H7B zinc finger CCCH-type containing 7B".

- 1 2 3 Vitour D, Lindenbaum P, Vende P, Becker MM, Poncet D (April 2004). "RoXaN, a novel cellular protein containing TPR, LD, and zinc finger motifs, forms a ternary complex with eukaryotic initiation factor 4G and rotavirus NSP3". J. Virol. 78 (8): 3851–62. doi:10.1128/JVI.78.8.3851-3862.2004. PMC 374268. PMID 15047801.

- ↑ Kang HJ, Koh KH, Yang E, You KT, Kim HJ, Paik YK, Kim H (February 2006). "Differentially expressed proteins in gastrointestinal stromal tumors with KIT and PDGFRA mutations". Proteomics. 6 (4): 1151–7. doi:10.1002/pmic.200500372. PMID 16402362.

Further reading

- Maruyama K, Sugano S (January 1994). "Oligo-capping: a simple method to replace the cap structure of eukaryotic mRNAs with oligoribonucleotides". Gene. 138 (1–2): 171–4. doi:10.1016/0378-1119(94)90802-8. PMID 8125298.

- Suzuki Y, Yoshitomo-Nakagawa K, Maruyama K, Suyama A, Sugano S (October 1997). "Construction and characterization of a full length-enriched and a 5'-end-enriched cDNA library". Gene. 200 (1–2): 149–56. doi:10.1016/S0378-1119(97)00411-3. PMID 9373149.

- Kikuno R, Nagase T, Ishikawa K, et al. (June 1999). "Prediction of the coding sequences of unidentified human genes. XIV. The complete sequences of 100 new cDNA clones from brain which code for large proteins in vitro". DNA Research. 6 (3): 197–205. doi:10.1093/dnares/6.3.197. PMID 10470851.

- Dunham I, Shimizu N, Roe BA, et al. (December 1999). "The DNA sequence of human chromosome 22". Nature. 402 (6761): 489–95. doi:10.1038/990031. PMID 10591208.

- Wiemann S, Weil B, Wellenreuther R, et al. (March 2001). "Toward a catalog of human genes and proteins: sequencing and analysis of 500 novel complete protein coding human cDNAs". Genome Research. 11 (3): 422–35. doi:10.1101/gr.GR1547R. PMC 311072. PMID 11230166.

- Strausberg RL, Feingold EA, Grouse LH, et al. (December 2002). "Generation and initial analysis of more than 15,000 full-length human and mouse cDNA sequences". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 99 (26): 16899–903. doi:10.1073/pnas.242603899. PMC 139241. PMID 12477932.

- Gerhard DS, Wagner L, Feingold EA, et al. (October 2004). "The status, quality, and expansion of the NIH full-length cDNA project: the Mammalian Gene Collection (MGC)". Genome Research. 14 (10B): 2121–7. doi:10.1101/gr.2596504. PMC 528928. PMID 15489334.

- Rush J, Moritz A, Lee KA, et al. (January 2005). "Immunoaffinity profiling of tyrosine phosphorylation in cancer cells". Nature Biotechnology. 23 (1): 94–101. doi:10.1038/nbt1046. PMID 15592455.

- Lim J, Hao T, Shaw C, et al. (May 2006). "A protein–protein interaction network for human inherited ataxias and disorders of Purkinje cell degeneration". Cell. 125 (4): 801–14. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2006.03.032. PMID 16713569.