Red Orchestra (espionage)

The Red Orchestra (German: Die Rote Kapelle) was the name given by the Gestapo to an anti-Nazi resistance movement in Berlin and to Soviet espionage rings operating in German-occupied Europe and Switzerland during World War II.

Name

The term "Red Orchestra" was coined by the Reichssicherheitshauptamt (RSHA), the counter-espionage arm of the SS, which referred to resistance radio operators as "pianists", their transmitters as "pianos", and their supervisors as "conductors".[1] Schwarze Kapelle (Black Orchestra) was the Gestapo's term for another group.

German counter-intelligence operations

The RSHA included three independent espionage networks in the "Red Orchestra": the Trepper group in Germany, France, and Belgium, the Lucy spy ring (German: rote Drei) in Switzerland, and the Schulze-Boysen/Harnack group in Berlin.

The Lucy ring included British spy (either a double-agent or, more likely, an accepted liaison officer) Alexander Foote, who later wrote about his role in his memoirs (Handbook for Spies).

On 13 December 1941 the Germans raided a house in Brussels from which they had detected clandestine radio transmission and caught two Red Orchestra agents and the housekeeper, Rita Arnould. Based on information given by Arnould they determined the book being used to encode messages and deciphered about 120 intercepted messages from June 1941, including one that had the addresses of the key Soviet agents in Berlin.[2]

In 1942 the RSHA established the Red Orchestra Special Detachment (German: Sonderkommando Rote Kapelle). It included representatives of the Gestapo, Abwehr, and the SD.[1]

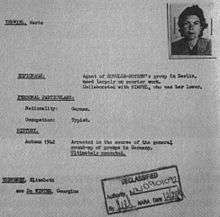

Trepper group

Leopold Trepper was an agent of the GRU. In early 1939, he was sent to Brussels, posing as a Canadian industrialist, to establish a commercial cover for a spy network in France and the Low Countries. Trepper established the cover firm the "Foreign Excellent Raincoat Company" in Brussels, an export firm with branches in many major European ports. Following the fall of Belgium in May 1940, he moved to Paris and established the cover firms of Simex in Paris and Simexco in Brussels. Both companies sold black market goods to the Germans and made a profit doing so. Belgian-born socialite Suzanne Spaak joined the Trepper group in Paris after seeing the conduct of the Nazi occupiers in her country.

Trepper directed seven GRU networks in France, and the network steadily gathered military and industrial intelligence in Occupied Europe, including data on troop deployments, industrial production, raw material availability, aircraft production, and German tank designs. Trepper was also able to get important information through his contacts with highly placed Germans. Posing as a German businessman, he held dinner parties at which he acquired information on the morale and attitudes of German military figures, troop movements, and plans for the Eastern Front.

In addition, contacts between the Simex company and its main customer, the Todt Organization, provided information on German military fortifications and troop movements. As a further bonus, these contacts supplied some of Trepper's agents with passes that allowed them to move freely in German-occupied areas.

In December 1941, German security forces shut down Trepper's transmitter in Brussels. Trepper himself was arrested on 5 December 1942 in Paris.[3] He agreed to work for the Germans, and began transmitting disinformation to Moscow, which may have included hidden warnings. In September 1943 he escaped and went into hiding with the French Resistance.

Operations by the Trepper ring had been entirely eliminated by the spring of 1943. Most agents were executed, including Suzanne Spaak at Fresnes Prison, just thirteen days before the Liberation of Paris in 1944. Trepper himself survived the war.

Schulze-Boysen group

The Schulze-Boysen, Harnack group in Berlin was formed by Harro Schulze-Boysen, a Luftwaffe staff officer, his wife Libertas, Arvid Harnack, a lawyer and economist, his American wife Mildred, and a number of sympathetic friends and acquaintances.

Schulze-Boysen had been active in opposition to the Nazis before Hitler took power, but then joined the Luftwaffe for "cover". In private, he continued to meet with other anti-Nazis, including Libertas, whom he married in 1936.

Harnack also had a circle of anti-Nazi associates. He joined the NSDAP in 1937 for "cover".

In 1939, the two groups made contact, and began to work together.

The combined group ran the gamut of German society, including Communists, political conservatives, Jews, devout Catholics, and atheists. Their ages ran from 16 to 86, and about 40% were women.

Among its leading members were theatrical producer Adam Kuckhoff and his wife Greta, pianist Helmut Roloff, secretary Ilse Stöbe, diplomat Rudolf von Scheliha, author Günther Weisenborn, potter Cato Bontjes van Beek, Horst Heilmann (a radio operator in the Cipher Section of OKH), and photojournalist John Graudenz (who had been expelled from the USSR for reporting on the Soviet famine of 1932–1933).

The group gathered intelligence from many sources. The group was not in contact with the USSR by radio.

For the remainder of 1941, the Schulze-Boysen/Harnack group gave most of its intelligence to the United States through the American embassy's monetary attaché, Donald Heath.[4]

However, these efforts to inform other governments about Nazi atrocities and war plans were only a small part of their resistance effort.

Their primary activity was the distribution of leaflets to incite civil disobedience and cause the Nazis to worry about subversion. They also printed and pasted up anti-Nazi stickers in large numbers, and they helped people in danger from the Nazis to escape the country via an Underground Railroad-like network.

The network began to unravel in 1942. The OKH Cipher Section decoded some of Trepper's radio traffic, and on 30 July 1942 the Gestapo arrested radio operator Johann Wenzel. Horst Heilmann tried to warn Schulze-Boysen, but the warning was not in time. Schulze-Boysen was arrested on 30 August, and Harnack on 3 September. The rest of the group was arrested within a few weeks, and many were executed.[1]

Red Three

The Red Three (German: Rote Drei) was the Switzerland section of Red Orchestra (code name: Foreign Excellent Raincoat Company), the espionage network of the Soviet Union in Western Europe, from 1930 until the end of World War II.[5]

- For more information see also

See also

- Plötzensee Prison

- Schwarze Kapelle

- White Rose

- FRG 1972 (TV Miniseries),

References

- 1 2 3 Richelson, Jeffrey (1995). A Century of Spies: Intelligence in the Twentieth Century. Oxford University Press US. p. 126. ISBN 0-19-511390-X.

- ↑ Rau, Peter (21 December 2012), "Ein legendäres Orchester", Die Linke (in German), retrieved 2017-11-26

- ↑ Brysac, Shareen Blair (2000). (Brysac, Shareen B.) Resisting Hitler: Mildred Harnack and the Red Orchestra. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 313. ISBN 0-19-513269-6.

- ↑ Brysac, Shareen Blair (2000). Resisting Hitler: Mildred Harnack and the Red Orchestra. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 225. ISBN 0-19-513269-6.

- ↑ The Ultimate Spy Book, by Dorling Kinderslay Ltd., London), The world of secret services, H. Keith Melton; ISBN 3-453-11480-9; p. 38 „The Red Orchestra“; Switzerland, Red Three.

- Trepper, Leopold (1977). The Great Game McGraw–Hill, Inc. ISBN 0-07-065146-9

- Brysac, Shareen Blair (2000) Resisting Hitler: Mildred Harnack and the Red Orchestra Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-513269-6

- Anne Nelson: Red Orchestra. The Story of the Berlin Underground and the Circle of Friends Who Resisted Hitler. Random House, New York 2009, ISBN 978-1-4000-6000-9.

- Guillaume Bourgeois: La Véritable Histoire de l’Orchestre rouge, Nouveau Monde, « Le Grand Jeu », 2015

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Rote Kapelle. |

- Plötzensee Memorial Centre

- BFCentral

- on Sophia Poznanska

- Book review of Red Orchestra by Anne Nelson. Random House website. Retrieved April 7, 2010

- L'orchestre rouge on IMDb