Roman diocese

The word diocese (Latin: dioecēsis, from the Greek: διοίκησις, "administration") means 'administration,' 'management,' 'assize district,' 'management district.' It can also refer to the collection of taxes and to the territory per se.

The earliest use of "diocese" as an administrative unit is found in the Greek-speaking eastern parts of Anatolia. Three districts, Cibyra, Apamea, and Synnada, were added to the Province of Cilicia in the time of Cicero, who mentioned the fact in his epistles. In the mid-third century 3rd century A.D. the word was applied to temporary districts within proconsular provinces of the 'populus,' like Asia and Africa which were more internal and less threatened. Starting with Gallienus, 253-268 these proconsuls were directly appointed by the emperor rather than being chosen by lot from among the senators. Often these proconsuls, who frequently served for more than one year, were attended by correctores assigned to districts, dioceses,' into which the larger provinces were divided.[1] However these subdivisions of provinces are not to be considered the antecedents of the later 'vicariate' dioceses created sometime between 298 and 313/14 which were regional conglomerates of provinces and numbered from 4 (Britain and Macedonia) to 21 (Oriens including Egypt until 370 or 380) and in total number from 101 in the Verona List if June 314 (from 47 in 284) to 118 in 395 in the Notitia Dignitatum.

Vicariate dioceses were governed by officials with the title of agens vices praefectorum praetorio. This title is formal and normative; it was used in full or as avpp on inscriptions (which give the office holder's career ladder -in Latin cursus honorum). The title means he who stands in for, acts on behalf of, represents, or manages instead of the praetorian prefects. There are variations of this title and circumlocutions in other sources such as 'vice sacra iudicans' for he who judges for the emperor on appeal; vicaria praefectura (substitute prefecture) and vicarius praefectorum (vicar of the prefects), vicarius illustrissimae praefecturae per dioceses (vicar of the most illustrious prefecture), administrans vices praefectorum (administering for the prefect), curans or gerens vicariam praefecturam (taking care of or administering the substitute prefecture), pro praefectis dioceses sibi creditas temperarunt (who regulate dioceses entrusted to them on behalf of prefects), qui vicariam egerint praefecturam (who controlled the substitute prefecture). The word 'vicarius' by itself is frequent and is the most common, informal abbreviation of the other longer titles.

Vicariate Dioceses

Synopsis: The appearance of the 'vicariate' dioceses is one of numerous innovations in the period from 260-345 AD that fixed the shape of imperial bureaucracy for almost 200 years; and was one of the innovations that inaugurated the [[Constantinian dynasty's adminisraive policy of "regionally based centralism."[2] Vicars were introduced to provide on-the-spot supervision and control conglomerations of provinces whose numbers had increased from 47 in 284 to 100+ by 305 AD ("The benefits of the subdivision of provinces were that each governor could devote more time to supervising the cities, transport and communications, and the food supply, and to hearing judicial cases from a smaller number of people. They could exercise a tighter control over a smaller number of taxpaying provincials that would have been the case if they has still governed larger areas. Control was the order of the day, as was prevention of rebellion," Pat Southern, The Roman Empire from Severus to Constantine, 2001 pp. 165-166, ISBC 0-415-23944-3; A. H. M. Jones, "The object was to tighten up the administration by giving governors a smaller area to control. A governor now had to divide his time between jurisdiction and finance. The latter had become a more complicated and troublesome matter, since beside the old money taxes, a multitude of requisitions had to be organized"..."and had a heavy burden of administrative work," A.H.M. Jones, Later Roman Empire, 1964, pp. 45-46, ISNB 0-8018-3353-1; Constanin Zuckermann, 'Sur la liste de Verone et la province de grande armenie, la division de l'empire et la date de creation des dioceses,' Travaux et Memoires 14, Melanges Gilbert Dagron 2002, pp. 627, 636-637). However, further major administrative changes re the division of competencies among the various ministries were not made after 314, if contemplated, before the last obstacle, Licinius, emperor in the East, was removed by Constantine in late 324. During the years 325-330 the emperor re-arranged and rationalized existing competencies between the prefects, the Treasury, the Res Privata and the Master of the Offices. These measures transformed the vicars from being the senior officials in the regions they governed to being the effective heads of the whole administrative apparatus after they were granted appeal jurisdiction in fiscal debt cases involving the Treasury (the Res Summa or from 318 Sacrae Largitiones) and Crown Estates (Res Privata). The transfer gave them the power to monitor the fiscal departments, but did not allow the vicars (or prefects) to meddle in the everyday operations of these two independent ministries. From the 380s the policy was very gradually reversed in fits and starts (and perhaps without so much thought as how it fit into the wider scheme of things). From the 360s one sees the rise of powerful praetorian prefects who encroached on the prerogatives of the Treasury and the Crown Estates in a series of off-and-on turf wars which the prefects had won by the 440s. The result was a return to the prefect/governor-centered two-tier administrative policy from the second half of the 5th century as had obtained prior to the creation of dioceses, even though on the books the intermediate tier was still in operation without much diminution of formal responsibilities.[2] The intermediate sphere was relegated though moribund, A. H. M. Jones, LRH I, 1964 pp. 280-282 ISBN 0-8018-3353-1; Errington, ibid; Jacek Wiewiorowski, The Judiciary of Diocesan Vicars in the Later Roman Empire, 2016, pp. 293, 297 299-301 ISBN 978-83-232-2925-4; L.E.A. Franks, Review of Wiewiorowski, Byzantinische Zeitscdrift, 2016, Band 109 Heft 2, p. 992.

The existence of a previously created set of 'fiscal' regional dioceses from the late 280s does not imply that the creation of the 'vicariate' dioceses was an inevitability. Good experience with the former may have been an influence to expand the innovation with the addition of the primarily judicial/supervisorial units to match the fiscal side.

Substitutes on the Provincial Level and in the Military; and a revised Tax System

Since diocesan vicars originated as substitutes, it is important to examine the development and greater use of these within the administrative history of the Later Roman State. Many of the substitute posts were regularized during the period 285-330 while some officials from the Principate were abolished. On occasion proconsular provinces during the Principate 27 AD to 284 AD subject to administrative reforms were governed by praetors who were one rank lower than consuls (both were the senior level officials of the Republic and Early Empire). Sometimes governors with extraordinary functions who were not proconsuls but equestrian 'vicarii' were sent to these provinces. [1] At other times financial procurators of the equestrian order were substituted for the regular equestrian governors in smaller provinces. They were called praesidial procurators (the most common terms for governor in the Later Empire were praeses, rector, moderator, iudex ordinarius). The use of ad hoc substitutes, vicarii, became common during the Crisis of the Third Century.

The use of substitutes in the military is seen with one type of general officer, the dux, who became a fixture in the Later Roman Empire as general of frontier units but whose origins are earlier. Originally this title was given to an officer who was acting in a temporary capacity at a higher than usual rank.[3] In the last decade of the 4th century a few duces appear with provinces as part of their titles, CAH XII, p. 123. This suggests the post was becoming permanent and being territorialized for general officers stationed along the borders (the duces' command often covered a perimeter province and one or more behind it inland). This development coincided with the gradual removal of military command from governors who were acquiring more financial duties from the financial procurators of the Treasury as the new tax assessment system came on stream, Cambridge Ancient History, XIII, pp. 174, 376-377 ISBN 978-0-521-30199-2 (citing M. H. Hendy, Studies in the Byzantine Monetary Economy, c. 300-1450, 1985 and J-M Carrie, 'Observations sur la fiscalite di IVe siècle pour server a l'histoire monetaire, in Camilli and Sorda, L'Iflazione, 1993, pp. 115-54). The exchange of competencies process was not perfectly synchronized. The creation of territorial duces and removal of governors' military command was almost completed by 311. Constantine deprived military command from the last few governors who possessed it very early in his reign.(J.C. Mann, 'Duces and Comites in the Fourth Century,' in D.D. Johnston (ed.) The Saxon Shore (C.B.A Research Report 18) 1977, 11–15).

Diocletian introduced a new tax assessment system in 287 that appears to have been coordinated with the creation of regional fiscal dioceses from 286 modelled on the pre-existing Egyptian district (including eastern Libya and Crete), and sets of massive censuses and property assessments which were not fully in place until the final years of the reign in 305. Italy south of the Appeninnes, heretofore free of direct taxation, was the last region to which the reforms were applied. The new system allowed imperial government for the first time to draw up a sort of budget, CAH XII, p. 175. The removal of the Treasury officials at palatine, regional and provincial levels from participation in the collection of regular in kind taxes and the operation of the Public Post was completed by 330 when the last of the Treasury provincial procurators were retired. Up to the mid-320s or so the officials of the Treasury, the Res Summa (the Sacrae Largitiones from 319) were ubiquitous in playing a major role in all fiscal affairs. The Annona Militaris, the separate supply distinct from the regular tax, was converted from requisition to a regular tax and was placed under the sole control of the prefects who managed it through the governors (and later vicars). The placement of army logistics and supple procurement with the civilian administration was designed to put a strangle hold on the military. When on transit, military units were accompanied by imperial notaries (an emperor's corps of secretaries), high-ranking agents from the staff of the Master of the Offices (a kind Minister of the Interior, State Security and Communications) to ensure they restricted themselves to orders and did not abuse or intimidate the civilian population.

Dioceses

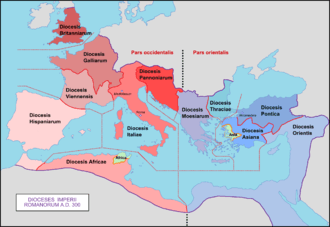

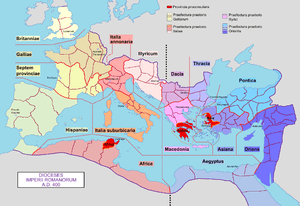

'Vicariate' dioceses were created sometime between 298 and 314. Diocese numbered from 4 to 20 provinces. In turn, they were grouped within territorial praetorian prefectures created circa 325-330. Numbers of provinces varied from 100+ to 120 at the beginning of the 4th and the end of the century. The dioceses initially numbered 12 (a 13th was added by 327 when Moesia was divided into Dacia and Macedonia; and Egypt was detached from Oriens in 370 or 380). They were not, however, the first regional supra-provincial management districts: this honor belongs to the 'fiscal' dioceses which preceded the 'vicariates' by 10–25 years from 298 to 313/14.

The 'general consensus' date for the creation of dioceses has been the year 298 or by 298 during the First Tetrarchy of 293–305.[4] The date was chosen by Theodor Mommsen. The source for the 'traditional' date is Lactantius' reference in De Mortibus Persecutorum 7.4, a work dated to 314/315, to "vicarii praefectorum" who are mentioned together with the regional comptrollers of the Treasury (rationales) and managers of the Crown Estates (magistri) as a triad who were working in tandem to further Diocletian's greed to raise revenue for his vast expenditures during the First Tetrarchy, 293-305 ). It has been argued that these vicarii prafectorum were diocesan vicars within defined territories as they appear in the Verona List dated to June 314: this date is the terminus ante quem. Others argue that the vicarii praefectorum were ad hoc, extraordinary vice-prefects on special assignments without formal districts and not the permanent vicars of regional districts on the grounds that no district is mentioned with any of those known pre-313/14, such as vicar of vice-prefect of Africa or of the Spains. Others have argued the co-existence of the two types for the period prior to 313/14. A number of scholars date creation post-305 to 312 (a time of civil wars among contenders for the throne). The year 313/4 has been proposed.[5] In any case it is not known which one or if Lactantius was thinking of both, although as court orator to Diocletian from about 295–303 and tutor in Trier to Constantine's son Crispus from 309, he was certainly in a position to know. The Verona List of vicars and dioceses of June 314 provides the latest date for the creation of the twelve vicariate dioceses. If vicars existed before 313 they had military command as did prefects and some governors who still had commands.

The model for the 'vicariate' dioceses is the 'fiscal' diocese of the Treasury (Res Summa or Res Summarum, from 318–19 the Sacrae Largitiones) headed by a rationalis, chief accountant or comptroller. The pre-existing Egyptian financial district was the model for the 'fiscal' diocese. In 286 it included Crete and Cyrenaica; the former was detached in 294 and joined to Achaia. Other 'fiscal' dioceses make their appearance within a few years suggesting that an empire-wide system was put into place under Diocletian.[6] The fiscal district also 'housed' the regional and provincial officials of the Crown Estates (Res Privata) under a manager, magister, subordinate to the comptroller (until the 350s). Until the late 320s or perhaps as late as 337 the comptrollers of the Sacrae Largitiones had provincial-level procuratores[7] It is uncertain the pace of the abolition. The discontinuance left the comptrollers without field managers, a situation which had a negative effect on the comptrollers to the benefit of the vicars and governors.

Various motives have been suggested for the creation of dioceses if the date 298 is accepted: to supervise the division of provinces begun slowly from the early 290s; to introduce the new tax assessment and collection system (which may have begun in 287 and involved a series of censuses every 5 years which took 15 years to complete and which gave the empire a budget in the modern sense for the first time); provide 'relief' officers to overburdened prefects;[8] if for the year 313, control of regions and demarcation of territorial rule between Constantine and Licinius (co-emperors until 324) at their 'Summit' in February have been suggested.[9]

Vicars

The diocesan vicars are the permanent territorialized expression of the ad hoc, extraordinary, and temporary substitutes, the agentes vices praefectorum praetorio, the vice-prefects so characteristic of the late Principate and early decades of the Later Empire as seen with the duces and types of governors. The vice-prefects, the presumed models for diocesan vicars, first appear during the Severan Dynasty, 193–235, as commanders of Praetorian Guard units for absent praetorian prefects. From the late 290s a few vice-prefects on special assignments outside Rome. Although very little is known about them or their activities (8 are known between 298-312) they appear to be 'trouble-shooters' tasked with putting right the affairs of a region after a rebellion (Egypt in 298), military campaign (in Morocco 298), supervising the division of provinces or heading up (Numidia and Libya 303) and the persecution of Christians (303 AD in Asia). Diocesan vicars retained the role of 'trouble-shooter' even after they were institutionalized and 'domesticated' but as regional internal administration supervisors. The ad hoc type of vice-prefect was fazed out in the 320s in favor of the use of comites provinciarum, chosen from among Constantine's closest confidants. The first appears in 316. About 20 served in 6 regions and a province (Spain, Africa, Macedonia, Asia, Oriens and Achaea); and unlike vicars their terms at times lasted for two years or more. The last was count of the Spains in 340. Their place was taken by mid- to high-ranking deputies from among the regular ranks of the bureaucracy on special assignment. The vicars whenever they appeared were 'dropped' into an existing system: it would not be until the years 325-330 that their full set of responsibilities was determined as the center of the Constantinian Dynasty's administrative policy, Errington, op. cit. p. 292.

The creation of permanent diocesan vicars 'outsourced' the power of the praetorian prefects who alone spoke for the emperor as his representatives, vices sacra iudicantes, CTh. 11, 30, 16 331, but it was superior not supreme because vicars' decisions could be appealed whereas the decisions of emperors and prefects could not be (though from 365 supplicatio, extraordinary appeal, to the emperor from a prefect's decision was allowed).. They had little discretionary power and were not policy-makers.[10] Praetorian prefects, urban prefects, vicars and proconsuls (and counts of provinces during their period of existence from 316-340) had first instance ordinary jurisdiction. Since they could not overturn the decisions of a lower court except on appeal they could have intervened in case of an irregularity in the lower courts. First instance jurisdiction provided them a mechanism for this and for them to take a case for cause.

From inception vicars exercised the highest authority within the diocese - as appeal judge - in spite of the fact that their rank of equestrian perfectissimus was the same as for the comptrollers and general managers of the SL and RP until they were elevated to senatorial rank in 326 (Delmaire, op. cit. p. 39 from inscription CIL II 4107; at the latest CTh. 8, 10. 2 (344). Superior authority did not mean complete control since they could not interfere in the routine operations of the two fiscal departments which were independent. The vicars' relationship to his two 'colleagues' was as ringmaster and not as sole arbiter, L. E. A. Franks, Byzantinische Zeitschfrift, 2016, Band 109, Heft 2, p. 991. Policies were set at the very top of the administrative pyramid by the senior officials and emperors. He was superior to the prefects of the Annona in Africa and Egypt: however, his role was general normally oversight, active monitoring, and if necessary investigation of their activities, not meddling. The prefects had their own administrative courts of the first instance.

The creation of permanent diocesan vicars 'outsourced' the power of the praetorian prefects who alone spoke for the emperor as his representatives, vices sacra iudicantes, CTh. 11, 30, 16 331. The vicars' decisions could be appealed whereas the decisions of emperors and prefects could not be (though from 365 supplicatio, extraordinary appeal, to the emperor from a prefect's decision was allowed). They had with praetorian prefects, urban prefects, and proconsuls (and counts of provinces during their period of existence from 316-340) first instance ordinary jurisdiction. Since they could not overturn the decisions of a lower court except on appeal first instance jurisdiction provided them a mechanism to intervene for cause such as corruption, intimidation of governor by a powerful local (CTh. 1. 15, 1, 325), irregular procedure, conflict of interest; the inadquancy of the governor, importance of the case, or the weight of public debt (Marican, Novella 1, 450). They had little discretionary power and were not policy-makers.[10] Praetorian prefects, urban prefects, vicars and proconsuls (and counts of provinces during their period of existence from 316-340) had first instance ordinary jurisdiction.

The vicars were from the beginning subordinate to prefects as seen in a law of 328 Constantine addressed to the prefect Aemilianus in Italy, "your vicars" (11, 16, 4). However, the exact degree of subordination is not entirely clear and is debated (Wiewiorowski, op. cit. pp. 40–41). They are described as "having a share of the prefects' authority" as if they possessed an independent power in its own right derived from the prefects' ("...technically independent of their jurisdiction, the vicars became in practice their subordinate administrative agents," William G. Sinnigen, 'The Vicarius Urbis Romae and the Urban Prefecture,' Historia, vol 8, No. 1 1959 p. 98; "the degree of subordination of these officials to the Praetorian Prefects, at least in some judicial matters is also uncertain" (Kelly op. cit. p. 185; cf. CTh. 11, 30, 9 = CJ 7, 62,16 (321); CJ 1, 54, 6, 2; CTh. 1, 15, 7 (377); Cledonius, “Tu autem vicarius dixeris et tua privigelia non reliquia, quando propria est jurisdictio quae a principe datur. Habes enim cum praefectis aliquam portionem,” 6, 15; Pallu de Lessert op. cit. p. 10 cites the Theodosian Code and Cassiodorus. He states the authority of the vicars derives from the emperor’s supreme judicial power and not from the prefects,”La vicaire jouit en ces matieres d’une competence proper; il n’est pas un delegue du prefet du pretoire;” “representatives with equal rights” (Noetlichs, op. cit. p. 74). Prefects could not overturn a vicar's verdict, appoint or dismiss him (provisional dismissal of a governor was allowed the prefect at the end of the century as one example of the rise of the prefects).

The vicars' main task was to control and coordinate the activity of governors (Southern, op. cit. p. 165). They were also supposed to protect governors from the intimidation of powerful, perhaps hostile, and unfamiliar local 'notables' (CTh. 1, 1, 15, 1, 325; it was a long-standing rule that governors could not serve in their native provinces or where they were legally domiciled to prevent collusion and influence Danielle, Slootjes, The Governor and His Subjects in the Later Roman Empire, 2006, p. 25). Constantine I was particularly concerned about the rich and powerful who oppressed the poor and tried to pass on tax they owed to the lower classes, John Noel Dixon, The Justice of Constantine, Law Communication and Control, 2012, p. 130, 198-200, ISBN 978-0-472-11829-8. The vicars' presence further reduced the governors' prestige (the number of governors had increased from 47 to 100+ by 305 and 120 by 395). On the other hand the presence of the vicars could shore up the authority of the governors Slootjes, op. cit. pp. 39–43; and they could intervene in justice matter as they had first instance jurisdiction which gave them the right to intervene. Unfortunately s it turned out for governors reduced prestige did not mean lessened responsibility or work load (for which they had only a staff of 100): they seem to have been under considerable pressure during their one-year terms of office and frequently in the cross-hairs of irate emperors (J-M Carrie et D. Feissel, Les gouverneurs dans l'antiquite tardive,' Antiquite Tardive, 2002; on pressures and manipulation of governors, Slootjes, pp. 79–104; Jones. op. cit. p. 399-400, on gubernatorial extortion and under-the-table deals, although all by no means were corrupt).

The vicars' role in the early years was mainly as appeal judges with general administrative oversight. Until the 320s they were less directly involved in financial matters because of the ubiquity of the comptrollers of the Sacrae Largitiones who were involved in almost all aspects of imperial finance (Delmaire, op. cit. pp. 197, 204, 245). The two officials were of the same rank although the vicar's authority was superior. The relationship of vicars to comptrollers may be illustrated by comparing it to that of governors with the controller of Egypt who received orders transmitted from prefects through governors which they executed, which in turn could trigger a response from them to the governor ( Lallemand, Jacqueline, L’aministration civile de l’Egypte de l’avenement de Diocletian a la creation du diocese (284-382) 1964, p. 86). The operational relationship prior to the changes made by Constantine was a kind of diarchy. An aspect of the vicars' responsibilities in fiscal matters before Constantine's major reforms of 325-329 may be illustrate this from a law in 319 (CTh. 1, 12, 2). Although addressed to the proconsul of Africa, the law is, nevertheless, pertinent because the posts of vicar and proconsul were virtually interchangeable: indeed the latter on occasion substituted for the vicars (Africa and Asia). The emperor instructed the proconsul to familiarize himself with all aspects of the administration and investigate the fraudulent reports of governors, comptrollers and the prefect of the Annona. They were in actuality on 'front-line' of tax collection supervision not vicars (praefectiani and vicariani were forbidden in normal circumstances from interfering with the tax collection activities of the lower levels unless deputed to do so; the former were sent out annually to stimulate the efforts of the governor and the latter to collect arrears Jones, p. 405, 457). This remained the operational 'rule' until 370s when the prefects and vicars are seen to intervene more in the affairs of the Sacrae Largitiones and Res Privata.

Broadly speaking, even though vicars were charged with exercising overall administrative control over the diocese, which included the Sacrae Largitiones and Res Privata,[10][11] they had to do it with a mixed armature of direct authority over the various components of the prefecture, i.e. governors and municipalities; and with limited control of targeted functions of the Treasury and Crown Estates. They did this as overseers of the regular courts of the prefecture. They were keepers of the global diocesan budget set by the prefects for the prefecture and the Sacrae Largitiones and Res Privata; guarantors of liturgical assignments (determined by the prefects issued by the governors to the liturgists); and deputy quarter-master generals of the armies. They had jurisdiction in criminal and civil cases over the imperial staffs of the prefecture, the SL and RP (except palace staffs and the staff of the masters of the offices); fiscal debt appeal cases and first instance of debt owed the prefecture; over Res Privata tenants in major criminal cases and the assimilation of confiscated property to the Res Privata which had to receive the approval of a governor (Jones, op. cit. p. 481-482).

The regulation that sealed the vicars' control of the diocese was the transfer of fiscal debt appeal cases from the administrative courts of the Treasury and Crown Estates to the prefectures of which vicars were a part (CTh. 11, 30, 28 of 359 refers to a ruling of Constantine which can be surmised to have been made 30 years previously. From 330-on the comptrollers who retained first instance jurisdiction in matters of debt (and other matters) - this authority was needed in order to preserve their independence from the prefects - are not seen to intervene in direct tax collection due them except on rare occasions when their offices were seen to lean ('une forte main') on the governors and vicars, Delmaire, op. cit.p. 245. The comptrollers did not have the bear responsibility for collection, but they did have to manage delivery (the special taxes in gold paid by senators, the golden crown and follis or gleba, were collected by the censuales, roll keepers of the Senate). To ensure proper performance by the governor the palatine counts of the Sacrae Largitiones could fine the governors and vicar for lax performance of duties relating to the Sacrae Largitiones, although this seems to have seldom occurred. The orator Libanius in Syria wrote twice on behalf of governors to have fines rescinded, once requesting the count of the Orient to intervene with the count of the SL, Delmaire, R., "the counts were able to slap fines on the governors," p. 90, governors, their staffs and curiales, ” p 244, from an edict of the emperor of Leo of 468, CJ, 10, 23, 3 and 4. They operated the mints, levied fines. They were able to keep importance and influence during the 4th century in spite of restrictions and demotion since they (and the Res Privata) provided the emperors with the most valuable and coveted part of their income, gold and silver. Cooperation among the three regional chiefs was expected. However, the comptrollers bereft of a permanent provincial-level staff post-330 gradually lost importance to the SL central office agents, the palatini, sent annually to verify the governors' efforts, but it was a slow decline which took almost 100 years. These agents, forbidden to have direct access to the provincials (though they did it anyway often) were supposed to work through the governors according to the written instructions they brought with them and which the governors had copies of (Delmaire, op. cit. p. 204–205, 244–245). Despite diminution until the end of the 4th century the comptrollers remained a critical link between governors, vicars and the palatine-level counts of the Sacrae Largitiones, as agents of surveillance (Delmaire, p. 204 ibid) and collectors of fiscal debt in the first instance, CTh. 6, 30, 4 (379) without the interference of the governor but in 398 the responsibility was handed over to the governors CJ 10, 19, 6. From time to time they pressured the vicars when stronger measures against governors were in order.

Post 330 CE

The years 325-330 had fixed the institutionalization of the dioceses as major players in imperial administration for a hundred years. These measures taken had had a ricochet effect the vicars who became more clearly senior to rationales in fiscal matters.[10] The changes had centralized tax debt appeal under the prefectures. However, as a precaution the Sacrae Largitiones and Res Privata administrative courts continued to have first instance jurisdiction (Jones, op. cit. p. 485-487), the retention of which was one way to prevent prefectural meddling in the affairs of their affairs (though they could not issue orders of any kind on their own authority to the provincials - these had to be approved by the emperor or a prefect, Delmaire, op. cit. 68 Delmaire, p. 68, “Ces edits sont pris de la proper autorite du comite, mais l’autorite de l’empereur ou du prefet du pretoire est necessaire quand ils doivent etre appliques par des instances provinciales sur lesquelles le comte n’a pas directement autorite, comme d’est le cas pour le tariff de Seleucie ). Appeal authority allowed the prefecture oversight at all levels. The shift of appellate jurisdiction to the higher courts of the prefecture brought the financial affairs of the three ministries together at the end of the process - the collection of debt on appeal - and at the starting point, the prefect's budget composition for all three ministries. This arrangement lasted until 385 when appeal jurisdiction was restored to the palatine counts of the Sacrae Largitiones and Res Privata who until this time acted in an advisory capacity before the prefects or emperors.

Likewise from 330 the vicars' competencies were for the most part fixed (by 337 according to Jacek Wiewiorowksi, The Judiciary of Diocesan Vicars in the Later Roman Empire, 2016, pp. 62-73). Their leading role was given expression by the Constantinian Dynasty (which lasted until 363) which "...favored a regionally-based centralism."[2] Circa 330 the word 'diocese' pertains only to the 'vicariate.' and ceases to be generic and becomes particular to a specific administrative unit (Delmaire op. cit. p. 171; Wiewiorowski, op. cit. p. 55, note 71 quoting CTh. 2, 26, 1 of 330). From 337 the vicars were in their 'salad days' in the 4th century with some carry over into the next.[10] The changes 325-330 were intended to break apart the prefects' powers thereby decentralizing the palatine level administration. It was done not structurally but by re-arrangement of competencies.

The vicars' duties were in sum: control and coordination of the activities of governors, as overseers of the regular courts, keepers of the global diocesan budget set by the prefects for the prefecture and the Sacrae Largitiones and Res Privata, as guarantors of liturgical assignments (determined by the prefects issued by the governors to the liturgists) and quarter-masters general of the armies. Their supervisory role was facilitated by the fact that the offices of the Sacrae Largitiones and Res Privata were located in the diocesan see city in all but a few cases (Corsica, Sardinia and Sicily). This is before they were given a few selective direct powers over the Sacrae Largitiones, the collection of in kind taxes and the State Post. Until the 360s their staffs were warned off from participation in actual tax collection - their task was supervision; however interventions of the vicars appear more frequently as the emperors went on revenue drives to make ends meet and increase ability to meet external challenges and larger tribal incursions. The list of competencies, however, remained formally on the books (Wiewiorowski, op. cit. p. 299). The causes of their decline must be discerned from other circumstances which affected their importance and performance.

The death of Constantine in 337 brings to a close the period of major administrative changes that began with Diocletian. These innovations fairly fixed the Roman Empire's basic governance structures for two centuries. These were the products of pre- and post-285 structures, innovations and competencies being mixed, remolded and adapted over a period of 50 years. (A.H.M. Jones, LRE, 1964, p. 207–208 for pace of commutation; pp. 401–410 'Centralisation' and the rise of the prefects; for and overview of administrative developments, The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Constantine, Ed. Noel Lenski, 'Law and Society,' Christopher Kelly, p. 184–204, The Cambridge Ancient History, XIII, The Late Empire A.D. 337-425, 'Emperors, government and bureaucracy,' pp. 138–184, Christopher Kelly; and Peter Heather, 'Senators and senates,' 'Institutional change,' p. 188–189, David S. Potter, The Roman Empire at Bay, 180-395, 1994, pp. 367–372). Justinian I for his part solidified the reversion to a two-tier administration - prefecture-province - that developed as a result of dioceses, except Oriens and Egypt, being side-lined post-440. He published a new Code of Laws, issued laws to strengthen the office of governor by forbidding sale of these offices, issued a standard set of instructions (mandata) to guide governors and abolished the remaining dioceses in the East, Jones op. cit. pp. 278–283; Jones suggests ibid "It might have been wiser, instead of abolishing the vicars, to have improved their quality by giving them better salaries, to have entrusted them with military powers to deal with internal disorders and a more effective appellate jurisdiction, which is what he did when he restored the diocese of Oriens in part covering northern Syria in 542 and Pontica in 548, ibid p. 294; however, these are not vicars in the old sense but two regional governors with extraordinary powers civil and military authority).

There remains the question when prefectures became administrative, a topic of much debate, and began to overtake the dioceses. The scholarly 'consensus' suggests the early regional prefectures from 325-330 were more spheres of control than administrative. The suggestions has been made that they served Constantine's dynastic plans (Timothy Barnes, Constantine: Dynasty, Religion and Power in the Roman Empire, 2011, pp. 293–298); and that the fully developed administrative prefectures as suggested by the 5th century author Zosimos is an anachronism more apt to the situation from 395 when the number was finally fixed. A more administrative character appears to be the case from the early 340s and even more so with the accessions of Valentinan I and Valens in 364 (Kelly, Christopher (2006). "Bureaucracy and Government". Ed. Lenski, Noel. The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Constantine. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-52157-4; Morrison, Cécile, ed. (2007), Le Monde byzantin tome 1: L'Empire romain d'Orient, 330-641 French Edition {{ISBN| 978-2-13-059559-5). If this chronological progression is correct it gives credence to the view that that primary administrative engine through the 4th century.

There is one more development that must be paid attention to. In the early 340s a last adjustment was made which had an important effect on vicars. It was decided to appoint senior agents, agentes in rebus (men of affairs, state investigators) from the master of the offices as heads of office in the prefectures, dioceses and two proconsulates. The Master of the Offices as the Head of State Security, Administration Oversight, Communications and, from the 340s, Inspector-General of the State Post, and Foreign Affairs. These outside 'plants, were not members of staff. This decision bound the diocese (and indirectly the other units of the diocese) to the MO. The main tasks of the Office Head, the princeps, was to monitor the performance of the staff; and to vet and countersign everything that came in and went out. The 'outsider' post also opened up a direct alternative channel of reporting to the palace. The presence of this senior courier/bureaucrat, the Gate-Keeper, familiar with many aspects of the imperial administration could have been a valuable asset to the vicar who also relied on the institutional continuity and memory of the several permanent staff heads and senior secretaries. The placement of a 'foreign' presence is but one of many checks-and-balances built into the system intended to clamp the several parts together and to promote mutual interdepartmental surveillance and accountability.

Lastly for understanding the role of the imperial superstructure above the provincial level (that would disappear after the collapse of the Empire in the West) it must be noted that the vaster amount of the actual administrative work was done by unpaid municipal liturgists and village heads (who were themselves taxpayers) under the immediate supervision of governors. The superstructure issued the orders, set the policies and goals that made the whole system go. It had evolved in response to the needs of a huge imperial State with a large professional army. Once that State ceased to exist, the superstructure disappeared or contracted. It numbered only 30-40,000, three or four times larger than previously and was incredibly small by modern standards. Mostly based in 125 provincial, diocesan see cities and in the capital(s) and, it was, therefore, out of sight for most of the time to the vast majority of the Empire's inhabitants - statutory size of the governor's and vicar's staffs were 100 and 300 respectively. Appointment of paid imperial officials at the local level to directly govern would have required a huge expansion beyond the capacity of the ancient state to fund. The diocesan, Sacrae Largitiones, and Res Privata were simpler versions of the administrative set-ups at the palatine top level: they were less complex with fewer departments: these office conglomerates located were information magnets for provincial and local administrations and processing centers for the palatine level. This fact did not preclude direct contact with the imperial court.

The fate of the fourteen dioceses was varied and dependent on internal administrative and policy changes during the 5th century; and external factors such as loss of territory due to occupation by tribal invaders). Decline has been attributed to incremental administrative centralization by praetorian prefects especially from the 380s as seen in the gradual take-over of the Treasury and Crown Estates ministries by the prefects and the palace chamberlains respectively after 450; a reversion to more two-tier governance prefects to governors in financial administration including the placement of prefectural tax officials with governors; more direct judicial appeals from governors to prefects; the general commutation of taxes in the 5th century from kind to gold which made collection and delivery, if not computation, much easier thereby lessening the importance of the intermediate tier; and abandonment or loss of dioceses to invaders. By 450 the Spains, Africa, and Pannonia were lost to invaders, the diocese of Britain having been abandoned in 410. The two Gallic dioceses were still in some degree of operation south of line from Cologne to Boulogne served by one vicar under the close control of the prefect of the Gauls in Arles. The diocese of Italy had had two vicars: the vicar in Milan (of Italy) who was discontinued and the vicar in Rome who continued to function fully as did those of Oriens and Egypt. These three with important duties connected to defense and provisioning the imperial capitals maintained importance in spite of the changes which diminished the other (Wiewiorowski, op. cit. p. 301). Thrace, Dacia, Macedonia, Pontus and Asia were slipping into redundancy. The last, Egypt, was abolished in 539 (for the rise of dioceses 340–410 and first indications of vicariate decline post as exemplified by the situation in Asia, Denis Feissel, 'Vicaires et proconsuls d'asie du iv au v siècle, Antiquite Tardive 6, 1998, pp. 103–104; the rise of the prefecture in the last decades of the 4th century that contributed to the decline of the Treasury and the Crown Estates after a 60-year struggle, Roland Delmaire, Les Largesses sacrees et res private, 1989 vols I & II, pp. 703–714). The consensus is that events in the 5th century had a very negative impact on the intermediate level governance which was effective in the 4th century.

The scholarly world has debated the degree to which dioceses were successful, and if so, why and whether their rise and decline was inevitable because of some 'design' flaw such as a lack of sufficient authority to perform what was expected of them as suggested by Wiewiorowski who sees the emperors' and highest officials' loss of confidence in the judiciary of the vicars in the very last years of the 4th century so after first few decades of the 5th they were mere embellishments, Wiewiorowski, op. cit. pp. 292–293, p 299 but he does not examine the fiscal role of the vicar; Franks for a review of first and appeal authorities of vicars, ibid, pp. 91–93; for a different and favorable assessment of Constantine's expedited appellate system, John Noel Dillon, The Justice of Constantine, Law, Communication and Control, 2012; and Franks, op. cit. p. 991 who suggests the increase in the importance of the vicars' fiscal role post-325 and the various procedural and regulatory means of control available to vicars over the administration counterbalanced any defects on the judicial side and "Everything points to vicars being in their 'salad days' until at least the end of the end of the 4th century with some carry over into the next (Franks. op. cit. p. 992); or to their inability to control governors and the territories were too large to manage.[12] It is possible from the evidence that a number of factors and contingencies affected the dioceses. Some fell prey to invasion and occupation in the West which saw the entire supra-provincial level administrative structure of the Roman State disappear except in Italy post-476 where it lasted virtually intact until the Byzantine invasion of 535. A good question is whether the effectiveness of the dioceses may have been undercut to some degree by the increased reliance on mercenaries - could this outsourcing of defense disrupted the normal operations of the civil administration which was designed to support a professional Roman army (whose gradual disappearance in the 5th century was a primary cause, if not the cause, for the collapse of the Western Empire)? Were dioceses incapable of responding effectively to challenges in the 5th century or were they gradually bypassed because circumstances in governance had changed except in the dioceses of Egypt, Oriens and vicar of Rome who ruled the southern part of the former diocese of Italy.[13]

Civil dioceses and the Reforms of Diocletian

The Roman administration had not been rationally planned at a go (which is not to say that responses were not rational or there was not rational planning), but was the product of several centuries of evolution. As a result lines of authority were at critical junctures porous; responsibilities were somewhat. Sets of administrative interdepartmental overlaps, inherited and developed, bound the system together in a some crazy-quilt fashion (Jones, Later Roman History, pp. 376–377; Age of Constantine, Ed. Noel Lenski, Christopher Kelly, 'Law and Society,' pp. 184–192 and Kelly Ruling the Later Roman Empire, pp. 206–210). Diocletian took the system he inherited, modified it, added, refined, and improved it but made no thorough overhaul. In fact it never was. The emperor saw a more interventionist imperial government involved in every aspect of governance down to the municipal level(Diocletian and the Tetrarchy, Roger Rees, 2004, pp. 22–23, 27, 90 whether "...working steadily towards its intended goal; or perhaps it suggests a rather arbitrary series of makeshift reactions"..."Whether or not there was any coherent political philosophy, or indeed government collegiality, are controversial questions," p. 39). After the death of Constantine the administrative structure was more or less fixed although the competencies within it were shifted about to get the desired or at least acceptable results. There appear to be three major clusters of reforms: in the mid-290s which dealt with fiscal matters and with increasing government efficiency; Constantine's reorganization of the palatine administration and the final removal of military command from prefects and governors in 312-14; and between 325-330 a partial rationalization of the administration system already in place.

Diocletian established mints near heavy concentrations of troops. He divided the 47 provinces beginning with the division of Italy in the early 290 into eight districts. By the end of his reign in 305 there were 100+ provinces (the number varied and went up to 120). Smaller provinces were more effective and easier to administer by governors who were given more judicial and financial responsibilities as their military commands were removed. The emperor ended the arbitrary army requisitions (plundering) which had become almost the norm during the years of crises and increasing high inflation which devalued the currency in the years 250–280 by instituting a separate tax (the Annona Militaris) whose collection and administration he placed with the prefects. He undertook censuses done by region with provincial variations in preparation for the introduction of a tax assessment system which gave the empire a regular budget in the modern sense for the first time. Due to debasement of the coinage 80% or more of tax came to be collected in kind (a common practice previously, but not so prevalent when goods and services could be paid in a stable gold and silver coinage). Even so, in-kind taxes were from time to time converted to payment in gold or silver, adaeratio, especially if it involved the payment of arrears - it was simply easier to do and did not involve expensive land transport charges associated with the movement of bulk goods). At times soldiers' in kind pay was converted to gold payments. Beginning in the reign of Constantine taxes were occasionally commuted to gold. The pace picked up modestly during the reigns of Valentinian I (364-375) and Valens (364-378) and quickened towards end of the 4th century as the treasuries accumulated more precious metal, Jones. op. cit. pp. 460–461. He tried to recreate the tri-metal stable coinage of bronze, silver and gold dating from the Augustan period, but this failed. If was in fact never restored although the gold aureus minted at 62 to the pound and lowered to 72 to the pound kept its value for centuries.

He transferred responsibility for military supply and logistics to the civilian administration in order to get a strangle hold on the army. It is claimed this caused log jams since supply was placed in the control of reluctant liturgists and contracting services directly with local populations.[14] He rebuilt the army after years of campaigns had sapped its strength (estimated strength of which varied from 389,704 + 45,562 in the fleets under Diocletian, according to John Lydus, a 6th-century bureaucrat of the prefecture of the East, to 645,000 by Agathias).[15]

He began much needed infrastructure repairs on roads, bridges and other public facilities after years of neglect. He tried to centralize the administration of justice with the governors (by banning the use of governor appointed judges, iudices pedanei to take cases in their place - with little effect; there were municipal courts which handled minor civil and criminal cases), but this overloaded the dockets of gubernatorial courts; he began the separation of civil administration from military command from governors (which Constantine completed in 312 at which time prefects were stripped of active command); made liturgies obligatory (free services provided the state and cities by private citizens either monetarily or in labor and supplies); furthered 'professionalization' of the bureaucracy by employing more salaried men of free birth until it was all men of free-birth by the time of Constantine (the service had evolved gradually from the mostly freedmen and slaves characteristic of large aristocratic households to something resembling the civil service of pre-modern times with civil service exams) w.[16]He tried to recreate the tri-metal stable coinage of bronze, silver and gold dating from the Augustan period, but this failed. If was in fact never restored although the gold aureus minted at 62 to the pound and lowered to 72 to the pound kept its value for centuries.

The emperor's interventionist policies changed the relationship of the imperial government to the municipalities in governance especially in tax matters. The traditional system of government since Republican times which had relied on participation of local elites whose continuation and success was fostered by imperial authority. The relationship was compromised by his encroachment on the customary spheres of control and operations of these elites. Instead of volunteering their services they tried to escape from the onerous burdens. Service became chore, Michael Whitby, Rome at War AD 293-696, 2002, p. 68, ISBN 1-84176-359-4. A prime example of this in tax policy illustrates the change. During the Principate the government had issued tax demands, indictiones, which the city councils allocated as they wished. From his reign the government not only issued and but also allocated the demands which was seen as n encroachment on local rights. The imperial bureaucracy tried to police the whole process at every level for each taxable community in order to hold it to its collective responsibility.[17] He made the collection and distribution of taxes in kind an hereditary obligation which required the enormous effort by members of the city councils and the taxpayers.

Town councilors were forced to perform liturgical duties for the State and their municipalities at their own expense, a long time practice that went back centuries. These were paid for in the Early Empire by the state, cities and by private individuals who donated funds to court the favor of the populace, gain honor and prestige, and leave visible memorials of their generosity. During the Later Empire private largess for public projects practically ceases. Neither the councils nor individuals wanted to pay out for the maintenance of civic amenities. Diocletian made them do it as an obligation. The liturgist was released from his obligation after performance over a number of years but the obligation was passed to his heir. Liturgies were of two types, patrimonalia, which were charges on property and involved expenditure and therefore as a form of tax, and personalia which were duties that required personal service, Jones, ibid. pp. 452, 724. The richer liturgists tried to shirk their duties by passing them on to the poorer or to attain senatorial rank which exempted them for their performance. The prefects drew up the lists, the vicars guaranteed and governors assigned (CTh. 11, 16, 4, 328 and passim) the performance of munera/leitourgia and munera sordida. Performance of munera personalia was “the exercise of a responsibility and sometimes physical work” such as performing corvee, doing road work, bridge construction and repair, burning lime, bread-making, and others. Other liturgical obligations included the extra provision of supplies and animals for the army, timber, the transport of food stuffs to the capitals cost of which was reimbursed (Jones. op. cit. p. . 452); production of horses and recruits, transport of food stuffs, animals and garments, the charge of the public post and provision of emergency animals, the buying of corn and oil for a city, heating of the baths, food inspection, police duties, collection and distribution of food, and the collection of tax in money instead of in kind, Jones, p. 749; CAH XII, pp. 365–366). Public works, opera publica, were paid for by rich, cities or the central government and built the lower classes to give employment or as forced labor: city walls, public buildings, baths, fiscal buildings, aqueducts, auditoriums, dye works, camps, churches, workshops, prisons, storehouses, martyries, palaces, colonnades, lighthouses, bridges, harbors, porticoes, Senate Houses, circuses, amphitheaters, gubernatorial residences, stables, temples and towers (Clyde Pharr, The Theodosian Code, 1948, p. 592).

He confiscated city lands and other properties, revenues and endowments and them placed to the Res Privata in trust. Julian returned them to the cities. Valentinian I returned one-third of the income ostensibly for the construction of city defensive walls. Management of the funds were later returned to the cities for the maintenance of cities' fabrics. The combined income from the municipalities acted as Equalization Fund from which monies could be directed to poorer towns for renovation of public infrastructure under gubernatorial and vicariate supervision.

Fiscal dioceses

Fiscal concerns were uppermost in the minds of the rulers. Without revenue the Empire could not exist (“The impression conveyed in the legal codes is that the interests of the state were primarily fiscal,” Peter Garnsey and C.R. Whittker, CAH XIII, ‘Trade and the Urban Economy,’ p. 316; “In general, the concerns of the government were narrow"..."The state was intent upon getting members of corportations (collegia) to perform various compulsory services – liturgies, corvees, sordida munera -- not to control their professional activities,” p. 318). Diocletian created the empire-wide system of 'fiscal' dioceses early in his reign in 286 on. It may have been introduced gradually as the new tax system was introduced or may have been created to supervise the censuses in preparation for the introduction.

The fiscal regime that Diocletian established introduced abstract measures of assessment, the caput and iugum, the combined land and head tax of the High Empire, called capitatio an assessment of a community's total tax liability. Ad hoc requisitions were scrapped and all liturgies, burdens, military recruitment and supply charges were incorporated into a single, unified fiscal vocabulary. A municipality declared its assets in a number of iuga based on individual tax returns. The resulting figure was used by the imperial censitores to assess the total tax burden, capitatio, in abstract units. Each of these capita would be earmarked as fulfilling a particular charge or liturgy. Conversion between iugum and caput was effected by means of conversion tables. The aim was to identify individuals responsible for the tax burden on field. The system of captitatio-iugatio determine the productive capacity of each field while the second, the individual responsible, was achieved by means of the origo, an administrative unit which could be laden with a proportion of a community's tax burden or a specific liturgy and which came to refer to the legal residence of those responsible for these: by means of orgiones, the landed wealth of municipalities could be compartmentalized, categorized and laden with a variety of liturgies, functiones, or fiscal burdens and enforced by the principle of collective responsibility. This was good from the government's perspective but created a static, idealized picture of agricultural activity, and the realities of economic behavior that relied on the mobility of labor. The result was a disparity between what was recorded on the tax rolls and the reality on the ground which was likely to create problems for the tax collector. The initiative to correct this disparity was place on the taxpayers form whom a constant stream of information was necessary and by providing communities with mechanisms by which they could request tax equalization, i.e. the redistribution of assets and burden of taxation, quoted from Cam Grey, Constructing Communities in the Late Roman Countryside, 2016, pp. 189-197, ISBN 978-1-107-01162-5. The vicars would be given the greater responsibility for making the system work post-330 (and of course in dioceses ruled by prefects!).

The fiscal diocese was not an invention of the emperor: it already existed in Egypt which was used as the model for fiscal dioceses empire-wide. The Egyptian unit had been headed by the Dioketes of the Res Summa in Egypt, Cyrenaica and Crete.[18] There is list of the earliest .[19] In 286 this official appears with a new title, Katholikos. His duties were the same as his predecessor's.[20] There are references to two more elsewhere in the very early 290s.[21] Even though the record is incomplete for the early period, it is assumed fiscal diocese existed in all regions under Diocletian.[22] Lactantius mentions them along with their subordinate managers (magister) of the Crown Estates, the Res Privata, (he magistri were junior to the comptrollers until the mid-350s when they were elevated to the same rank as the comptrollers of the Treasury) during the First Tetrarchy, 293-305. Such an expansion would have fit in well with the taking of empire-wide censuses and the introduction of the new tax assessment system. Both officials are attested to in Egypt in 298 (two Sacrae Largitiones procurators assisted the comptroller). Both officials are attested to in Egypt in 298 (two Sacrae Largitiones procurators assisted the comptroller). The 'fiscal' diocese 'housed' the Crown Estates (the Res Privata),.[23] The jurisdictional lines were not the same for both everywhere because the Res Privata estates were delineated within provinces while the jurisdiction of the Treasury was contiguous with provincial boundaries. Both officials reported to respective palatine superiors who were attached to the emperor's personal entourage. The Treasury officials worked with the governors to whom the prefects transmitted their orders pertaining to financial matters and the budgets. The SL comptrollers and the Crown Estate managers received the tax demands and rent rates from the annual publication of the budgets.

The Treasury raised revenue from many types of taxes paid in gold: the aurum coronarium, supposedly a voluntary contribution 'offered' by cities on the accession of an emperor, on the 5th anniversary of the accession and the celebration of an Triumph; an equivalent tax from the senators called the aurum oblaticium (or oblatio senatoria)- these two taxes seem to have been timed to the quinquennial donative to the troops. Two taxes (to procure more gold revenue) were instituted by Constantine the collatio glebalis or folles, a property tax assessment on senators (above the amount of regular tax paid by their estates) and the collatio lustralis tax paid in gold by businessmen and -women. The latter tax was levied on assets. It is recorded the city of Edessa (now Urfa in Turkey near the Syrian border) paid 35 pounds per year or 2,520 solidi. An estimate suggests Egypt paid 1,400 pounds a year or 100,000 solidi a year[24] The aurum tironicum was a commutation of the recruit tax usually in the amount of 25 or 30 solidi per man to pay for barbarian mercenaries. Horses and mules for the army were requisitioned. Additional revenue was raised from fees, rents, leases, surcharges, licensing fees, sales tax, transit dues (the quadragisima Galliarium at 2.5%), tolls such as harbor dues and city gate tax (appropriated to the treasury by Constantine), excise tax paid by merchants, customs and import taxes, taxes on mines and quarries, fines of various sorts; tax on the means of production, mortgages, interest payments, and prostitution. The State resorted to the practice of demanding gold and/or silver from individuals at a price fixed by the government, aurum comparaticum, in order to get at private hordes.[25] The Treasury paid cash stipendia to officials and soldiers and the accession donatives of the latter. It produced, collected and distributed clothing to the court, military and civil service. The Treasury operated the state armories, mints and leased mines to private contractors; funded and maintained imperial palaces and other facilities.

The Res Privata, the Crown Estates, supplied income to the emperors from rent and taxes on leased or managed imperial lands which until 366 could be paid in kind or in gold or silver: afterwards only in the latter. Most of the Res Privata was actually let out to private individuals who paid rent and regular tax. Res Privata lands were exempted from supplemental levies and liturgies. The density of these estates across the empire was uneven. The percentage of Crown Property was very high in Tunisia and eastern Algeria, parts of Italy, Bithynia, Cappadocia, and Palestine; within the territory of the city of Cyrrhus in northern Syria 16% of the registered land was imperial "But Cyrrhus may well have been exceptional" it had been the home of Avidius Cassius whose estates were confiscated after his rebellion against Marcus Aurelius, Jones op. cit. p. 414-416. There is little information to estimate the amount of rent and revenue paid on the imperial land.

The Res Privata operated clothing mills and dye works. In the West half the Res Privata income went to the Sacrae Largitiones.[26] Prior to 366 Res Privata rent and taxes could be paid in kind or in gold and silver; afterwards in specie only. The discontinuation of in kind payments may have come about as the consequence of imperial financial duress occasioned by the extravagances of Julian, the cost of his ruinous Persian War and the massive need for gold and silver to pay two accession donatives of Jovian in 363 and Valentinian I and Valens in 364 to 600,000 soldiers (83,334 pounds each year, a sum equal to 28% of imperial revenue estimated 300,000 pounds of gold per annum)[27] who embarked measures to restore financial health including revenue drives.[28].

Until the 360s the Res Privata with its vast local agents and staff was able to collect its own rents and taxes, A.H. M, Jones, LRE I, p. 414. Perhaps because of duress in imperial finances from the mid-360s governors were assigned supervision of the collection of Res Privata rents (lands paid rent and regular tax referred to as 'rent'). The result was massive arrears in the 370s. Theodosius I in 382 ordered collection to be transferred back to the rationales. The same change was ordered by Valentinian II in the West. In 395 and in 399 the policy in the West had been reversed twice leaving collection in the hands of the governors. In 394 the count of the Orient was involved in RP revenue collection. The count's request for additions to his staff of 600 to carry out the collectiond. From 399 collection in the West lay with the governors under supervision of palatini (of the RP) sent down from central office; in the East it is not entirely clear from the two pieces of evidence whether it solely under the governors or in concert with the rationales of the RP, Jones, ibid.

Before the 5th century the fiscal ministries supplied the emperors with the bulk of their income in gold and silver (until 366 payment of tax and rent in gold and silver to the Res Privata was optional). In the Western half if the Empire the revenue of the Res Privata was directed to the Sacrae Largitiones which was still in charge of both departments into the 5th century, not so the Res Privata in the East whose revenue went solely to itself. The two fiscal ministries in many respects were two sides of the same coin as they operated in tandem. For example, the Sacrae Largitiones in the West supervised the Res Privata and received some of its income; and the heads and some officials from one department sometimes performed duties for the other.[29] The income was spent within the provinces or dioceses as needed or directed to the emperors. The heads of the Sacrae Largitiones and Res Privata which were held accountable for the collection and distribution of the revenue due their ministries whether their agents collected or not. Most of the emperors' income in gold and silver came from the Sacrae Largitiones and Res Privata before the commutation of the prefects' in kind land tax revenue (80% of total income) got underway more rapidly very late in the 4th in the early 5th centuries,[30] a trend which eventually contributed to making redundant the palatine and regional fiscal departments and the dioceses.[31] The use of income from the Res Privata was at an emperor's discretion and sense of munificence: he could use it for personal gifts, civic donations, palace expenses: it was used regularly to supplement the regular budget of the prefects. For example, the giant expedition against the Vandals (a flop) was financed by the prefects, the Treasury and the Crown Estates.

Before 325 the regional rationales (whose superiors and staffs resided with the emperors) were ubiquitous. They were involved in almost every aspect of tax collection it seems,[32] except for the Annona Militaris which from its inception was solely prefects' responsibility as quarter-masters general of the army. Although the prefects had lost active military command they became even more so as effective heads of the imperial commissary and logistics supply systems. They did not however have sole control over all in kind tax collection which was still shared with the Treasury. Constantine changed this. He confined the Sacrae Largitiones and its regional rationales to oversight of money tax collections in precious metals at a time when the gold coinage, the solidus (fixed at 72 to the pound by Constantine in 309), was contributing to the stabilization of imperial finances. He split the treasury into three parts, each prefect, Sacrae Largitiones and Res Privata having his own (the accounts were always separate pre- and -post division). He transferred appeal jurisdiction over Sacrae Largitiones and Res Privata fiscal debt cases between 327 and 329 to the prefects and vicars (the governors already pronounced sentences of confiscated property for assimilation to the Res Privata).[33] He abolished the remaining provincial Sacrae Largitiones procurators of the comptrollers which left the Sacrae Largitiones without a field force to supervise collection its own taxes.[34] The lack of provincial-level Sacrae Largitiones staff was made up by transferring their role to the governors under the control of the prefects and vicars and monitoring by the comptrollers. The rationales continued to have numerous minor agents to look after their affairs in many cities: these were the imperial officials called the largitionales civitatum or urbium singularium (in Italy and Gaul there were also had regional largitionales). The comptrollers' collection duties largely devolved upon the governors who already had responsibility for the prefects' tax revenues. The rationales remained responsible for the actual collection performed by others, and personally for distribution to the designated Sacrae Largitiones provincial, diocesan or palatine treasuries. Their staffs, transport service (the bastaga) and guards transported specie. They conducted first instance trials for debt, and directed the special agents of the Sacrae Largitiones who were sent annually from central command to stimulate the governors' tax collection efforts for the Sacrae Largitiones.[35] The comptrollers watched the vicars and governors and themselves were watched by the vicars. They plus the Res Privata managers were conveniently located almost everywhere in the diocesan see cities. In one case, diocese of Africa, the diocese managed the Sacrae Largitiones accounts,[36] a clear case of encroachment during a period, the 370s to 382 when governors were supervising the collection of Res Privata rents - which led to massive arrears, a very poor policy decisions since they didn't have the staff to do it. One year after the transfer of Sacrae Largitiones and Res Privata appeal debt to the prefecture the first reference appears of 'diocese' to denote a region governed by a vicar, the word reserved thereafter exclusively vicariate dioceses.[37]

On the other hand, Constantine's reforms left the Res Privata's provincial structure intact, no doubt because of the vastness of the land holdings and the desire to keep it out of the hands or influence of the prefectures. Most of the Res Privata's holdings were not actually managed by the RP but leased to private individuals (conductores). That portion under direct control was administered by a network of local managers, the actores, under the direction of provincial procurators and the regional managers, the magistri. The leased properties, the patrimonium, paid rent and regular tax but was exempt from supplemental tax demands and the performance of liturgies (which made it very attractive, if a good investment, to private parties these were in effect permanent tax holidays - but it did attract people who wanted to shift ownership of their private lands to the Res Privata surreptitiously). Tax holidays were given on the condition that lands were brought under cultivation. Until the 360s the Res Privata managed the collection of rent and taxes. However, in the 370s governors were assigned to supervise the collection from time to time.[38] Unfortunately the results were huge arrears The experiment was ended in the early 380s. The in the 390s it was resorted to again By the end of the century it lay with the governors in the West and jointly in the East with the rationales (the two laws in CJ give both so it is unclear whether the collection was joint or not).[39] Towards the end of the 4th and beginning of the 5th centuries vicars are occasionally seen involved in direct supervision of Res Privata rents and the regular tax on Res Privata land which was owed the prefecture.[39] Eventually the Res Privata fell under the power of the Palace senior chamberlain.[40]

After reforms of 325-329 the two fiscal ministries remained independent: the prefects and their agents could not interfere with their normal routine operations unless given permission or instructed to do so. The prefects, however, possessed brakes on the two fiscal departments: they could not independently issue instructions, orders, timetables, dispatch deputies or initiate actions of any kind involving provincials without the prior approval of themselves or the emperor (dispostiones (administrative regulations, timetables, schedules), mandata (instructions, orders) and commonitoria (orders and memoranda) had to be confirmed, when the provisions contained in these had to be enforced by provincial authorities over whom the counts of the SL have no direct authority (but did have ways of putting the pressure on governors such as fines for poor service in collecting the income due the department).[41] Ability to do this would reversed the rationalization of competencies. The prefects (no doubt with imperial approval and input from the ministers meeting in consistory) set policy and tax rates for the Sacrae Largitiones and Res Privata with imperial approval. SL deputies had to present themselves with their instructions to the governors who had separate copy of these. They had to carry out their orders through the governors who in turn could not interfere with them unless they transgressed: i.e. the governors supervised the collection for the SL. The SL staff and the comptrollers monitored the governors' performance and pressured them if necessary, Delmaire op. cit. p. 203-204. SL staff in the provinces were instructed to collect arrears through the courts and staff of the governors. Often they tried to do this directly on their own which made them subject to disciplinary action or arrest if they were found out. Such was the pressure to extract taxes it may be wondered how effective the threat was since these are repetitive.

The controllers were equestrian perfectissimi well into the 360s indictative of their junior status compared to the vicars. The first comptroller of senatorial rank was a Katholikos of Egypt ' in the 340s perhaps in recognition of this post's importance in the fiscal life of this rich province. The other comptrollers had to wait till the 360s and later. By the end of the century all were of senatorial rank (as were governors) as grade inflation within the mid-levels of the bureaucracy proceeded apace.

The three regional officials made up a triad of senior regional officials in an intermediate tier. The duties and functions of the two regional Sacrae Largitiones and Res Privata officials and the vicars converged, and overlapped operationally at some points in particular with governors who had a hand in supervising the collection of SL taxes, and those of the RP off and on from the 370s (until this was made permanent around 400 AD). The overlaps provided officials with mutual checks on each other in a system that was constructed to "ensure that senior office holders might police the actions of their colleagues."[42]. The administrative triangulations seen at every level were pervasive, if asymmetrical and incomplete. The check-and-balances the overlaps provided are typical of the system which used a scatter-gun approach of group accountability and culpability (backed up by threats of fines for whole departments) to maintain control of an out-of-sight and distant bureaucracy. The prohibition to stay away from the Sacrae Largitiones applied even more strictly to the Master(s) of the Offices, Ministers of Internal Security, were forbidden from having anything to do with the Sacrae Largitiones. [43] On the other hand, from the 340s the masters were 'represented' by senior agentes in rebus who were appointed as heads of the office in the prefectures, dioceses and two of three proconsular provinces; and by field inspectors of the public post who were stationed in diocesan and provincial see cities and other towns and cities such as ports. These administrative arrangements were parts of a series of overlapping triangulations clamped independent departments of State together with shared duties at discrete junctures.

Finally evolution and fates of all three regional officials are intertwined. Their decline converges in the mid-fifth century (without suggesting absolute synchronicity) as the prefects and palace administration gained more direct control over the Sacrae Largitiones and Res Privata respectively and the prefects bypassed the vicars in favor of greater direct contact with governors.[44]

Prefects and vicars

Augustus created the post of praetorian prefect to command the Imperial Guard. It personal without territorial jurisdiction. The praetorian prefect by the reign of Diocletian had evolved from being a commander of the Imperial Guard to being vice-regent, "a kind of grand vizier" (Jones, op. cit. p. 371). The post had acquired important judicial, financial and administrative authority over the entire administration. He was commander of the armies, an associate chief justice of the emperor, head of administration, chief quartermaster-general of the army, and head of finance. Diocletian did not address the problem of task overload (this was left to Constantine after the defeat of Licinius in late 324). He kept the 'canonical' number of prefects at two even during the Tetrarchy: the Caesars had to do without. Constantine I broke with precedent by appointing Bassus in 318 as the third prefect for his son Crispus who had been put in charge of Britain and Gaul in 317. The number increased to four by 331, if not earlier. A fifth for Africa existed in the years 335–337. After the emperor's death in 337 the number reverted to three, one for each of his three son successors. Numbers varied from three to four until four as the 'canonical' number was fixed in 395 for Gaul, Italy, Illyricum and the East: These four existed from 342/43 to 361, from 375 to 379 and from 388 to 391.

Constantine beginning in 312 made innovations in the palatine administration but tentatively since he had an imperial colleague to deal with, Licinius, until November 325. He stripped the prefects of active military command which in any case they had not used for some time (vicars did not have military command if created post-312). The final removal separation of military command from prefects and governors created a purely civilian administration and military. The former had superior authority over the latter. There considerable evidence of friction between the two, Jones, op. cit. 376 including evidence of military attempts to encroach on the prerogatives of the civilian sphere in matters of supply procurement (such as violation of procedure by going around the civil authorities and making requisitions without their permission) and occasional illegal trials of civilians as defendants in courts-martial.

The emperor and Licinius founded the high-ranking imperial notaries who were the private corps of secretaries (and imperial emissaries). He made the Tribune of the Guards, the Scholai. He appointed him head of the imperial secretariats (the scrinia) between 313 and 315 and gave him the additional title of master of the offices. He placed the corps of imperial couriers the agentes in rebus under this tribune. He changed the name of the Res Summa, the Treasury, to Sacrae Largitiones by 319 (Kelly, op. cit. pp. 188–190 for these changes; cf. David D. Potter, The Roman Empire at Bay, pp. 71–172).