Rising Sun Flag

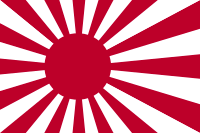

The Rising Sun Flag (旭日旗 Kyokujitsu-ki) was originally used by feudal warlords in Japan during the Edo period (1603–1868 CE).[1] On May 15, 1870, as a policy of the Meiji government, it was adopted as the war flag of the Imperial Japanese Army, and on October 7, 1889, it was adopted as the naval ensign of the Imperial Japanese Navy.[2] It is still used in Japan as a symbol of tradition and good fortune, and is incorporated into commercial products and advertisements. The flag is currently flown by the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force and a modified version is flown by the Japan Self-Defense Forces and the Japan Ground Self-Defense Force.

History and design

The flag of Japan and the rising sun had symbolic meaning since the early 7th century in the Asuka period (538–710 CE). The Japanese archipelago is east of the Asian mainland, and is thus where the sun "rises". In 607 CE, an official correspondence that began with "from the Emperor of the rising sun" was sent to Chinese Emperor Yang of Sui.[3] Japan is often referred to as "the land of the rising sun".[4] In the 12th-century work, The Tale of the Heike, it was written that different samurai carried drawings of the sun on their fans.[5]

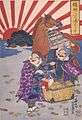

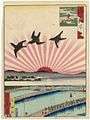

A well-known variant of the flag of Japan sun disc design is the sun disc with 16 red rays in a Siemens star formation. The Rising Sun Flag (旭日旗 Kyokujitsu-ki) has been used as a traditional national symbol of Japan since the Edo period (1603 CE).[1] It is featured in antique artwork such as ukiyo-e prints through history. Such as the "Lucky Gods' visit to Enoshima", ukiyo-e print by Utagawa Yoshiiku in 1869 and "One Hundred Views of Osaka, Three Great Bridges", ukiyo-e print by Utagawa Kunikazu in 1854. The Fujiyama Tea Co. used it as a wooden box label of Japanese tea (green tea) for export in the Meiji period / Taisho period (1880s).[6]

The Japanese word for Japan is 日本, which is pronounced Nihon or Nippon and literally means "the origin of the sun". The character nichi (日) means "sun" or "day"; hon (本) means "base" or "origin".[7] The compound therefore means "origin of the sun" and is the source of the popular Western epithet "Land of the Rising Sun".[8] The red disc symbolizes the sun and the red lines are light rays shining from the rising sun.

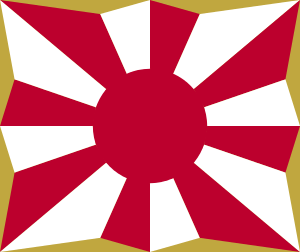

It was historically used by the daimyō (大名) and Japan's military, particularly the Imperial Japanese Army and the Imperial Japanese Navy. The ensign, known in Japanese as the Jyūrokujō-Kyokujitsu-ki (十六条旭日旗), was first adopted as the war flag on May 15, 1870, and was used until the end of World War II in 1945. It was re-adopted on June 30, 1954, and is now used by the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force (JMSDF). The Japan Self-Defense Forces (JSDF) and Japan Ground Self-Defense Force (JGSDF) use a variation of the Rising Sun Flag with red, white and gold colors.[9]

The Rising Sun Flag has been used as a traditional national symbol of Japan since at least the Edo period (1603 CE).[1] It has been used in many ukiyo-e prints through history. For example the "Lucky Gods' visit to Enoshima", ukiyo-e print by Utagawa Yoshiiku in 1869 and "One Hundred Views of Osaka, Three Great Bridges", ukiyo-e print by Utagawa Kunikazu in 1854. The Fujiyama Tea Co. used it as a wooden box label of Japanese tea (green tea) for export in the Meiji period / Taisho period (1880s).[6]

The design is similar to the flag of Japan, which has a red circle in the center signifying the sun. The difference compared to the flag of Japan is that the Rising Sun Flag has extra sun rays (16 for the ensign) exemplifying the name of Japan as "The Land of the Rising Sun". The Imperial Japanese Army first adopted the Rising Sun Flag in 1870.[10] The Imperial Japanese Army and the Imperial Japanese Navy both had a version of the flag; the naval ensign was off-set, with the red sun closer to the lanyard side, while the army's version (which was part of the regimental colors) was centered. The flag was used until Japan's surrender in World War II during August 1945. After the establishment of the Japan Self-Defense Forces in 1954, the flag was re-adopted and approved by the GHQ/SCAP. The flag with 16 rays is today the ensign of the Maritime Self-Defense Force while the Ground Self-Defense Force uses an 8-ray version.[11]

Present day use

Commercially the Rising Sun Flag is used on many products, designs, clothing, posters, beer cans (Asahi Breweries), newspapers (Asahi Shimbun), bands, manga, comics (e.g., Fantastic Four/Iron Man: Big in Japan, June 2006), anime, movies, video games (e.g., E. Honda's stage of Street Fighter II), etc.[12] The Rising Sun Flag appears on commercial product labels, such as on the cans of one variety of Asahi Breweries lager beer.[12] The design is also incorporated into the logo of the Japanese newspaper Asahi Shimbun. Among fishermen, the tairyō-ki (大漁旗, "Good Catch Flag") represents their hope for a good catch of fish. Today it is used as a decorative flag on vessels as well as for festivals and events. The Rising Sun Flag is used at sporting events by the supporters of Japanese teams and individual athletes as well as by non-Japanese.[13]

The Rising Sun Flag is the war flag and naval ensign of the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force (JMSDF) since June 30, 1954. JSDF Chief of Staff Katsutoshi Kawano said the Rising Sun Flag is the Maritime Self-Defense Force sailors' "pride".[14] The Japan Self-Defense Forces (JSDF) and the Japan Ground Self-Defense Force use the Rising Sun Flag with eight red rays extending outward, called Hachijō-Kyokujitsuki (八条旭日旗). A gold border lies partially around the edge.[9]

The flag is also used by non-Japanese, for example, in the emblems of some U.S. military units based in Japan, and by the American blues rock band Hot Tuna, on the cover of its album Live in Japan. It is used as an emblem of the United States Fleet Activities Sasebo, as a patch of the Strike Fighter Squadron 94, a mural at Misawa Air Base, the former insignia of Strike Fighter Squadron 192 and Joint Helmet Mounted Cueing System with patches of the 14th Fighter Squadron. Some extreme right-wing groups display it at political protests.[15]

Controversy

Due to the flag being used by the Imperial Japanese military and Japan's actions during World War II, it is considered offensive by certain people in Asian countries especially Korea,[16][17][18] formerly ruled under Japan, and China,[19][20] and some American veteran groups who participated in the WWII.[21] The symbol is claimed to be associated with Japanese imperialism in the early 20th century[16][17][18][19][22][23][24] because of its use by Japan's military forces during that period.

The Republic of Korea hosted a navy fleet review at Jeju Island on October 10 to 14, 2018. South Korea requested all participating countries to display only their national flags and the flag of the Republic of Korea on their vessels. Japan balked at the demand, with the then-Defense Minister Itsunori Onodera, since replaced, claiming the display of the Rising Sun Flag should be mandatory under Japanese law. South Korean Foreign Minister Kang Kyung-wha urged Japan to be more considerate about Japan's controversial colonial rule of the Korean Peninsula and stated that her ministry will review "possible and appropriate options" before deciding to take stronger international actions when asked whether South Korea could raise the issue with the United Nations.[25]

Japan announced on October 5, 2018, that it will be withdrawing from the fleet review because it could not accept Seoul's request to remove the Rising Sun Flag. Defense Minister notified the South Korean government of its decision. Both nations reiterated the need for continued defense cooperation.[26]

Although they protest the Rising Sun Flag, no country prohibits from using it by law. For instance, due to international law the South Korean Navy's position is that there are no problems with the carrying of the Rising Sun Flag on-board warships of the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force. According to officials, it would be an infringement of Japanese sovereignty if the Korean Navy requested that the ships not carry the Rising Sun Flag.[27] Koreans often compare the Rising Sun Flag with the Nazi flag[28] and perceive the continued use of it as a signal to not admitting the past war crimes of a previous imperial government.[29]

Comparisons with the Nazi flag of Nazi Germany are disputable, because the swastika was a random symbol of non-German, Hindu mythology. The swastika is an important Hindu symbol.[30][31] The word swastika is ancient, derived from three Sanskrit roots "su" (good), "asti" (exists, there is, to be) and "ka" (make) and has meant a "making of goodness" or "marker of goodness".[32][33] Its symbolism for motion and Sun may be from shared prehistoric cultural roots, according to Norman McClelland.[34] The Nazi flag with the Hakenkreuz and white disc centered was used throughout (1920–45) as the NSDAP party flag (Parteiflagge). Between 1933 and 1935, it was used as Germany's national flag (Nationalflagge) and merchant flag.[35] It can be banned since it was only ever used by the Nazis in Germany and it looks very different to the traditional German flags. By comparison, the Japanese only really had two national flags: the Flag of Japan (Nisshōki (日章旗, the "sun-mark flag")) is the classic red circle and white background. The red circle is called Hinomaru (日の丸, the "circle of the sun"). It embodies Japan's sobriquet: Land of the Rising Sun.[36] The second national flag of Japan is the Rising Sun Flag which is the sun disc with 16 red rays. The ensign is known in Japanese as the Jyūrokujō-Kyokujitsu-ki (十六条旭日旗). To compound the matter further, the Rising Sun Flag had been in use for centuries by the Japanese and had been the official flag of the Japanese Navy since May 15, 1870.[1][9] A stylized version of the Iron Cross called the Balkenkreuz (beam-cross) was used as a military flag and emblem by the Wehrmacht (Armed Forces of Germany) during the Nazi regime.[37] The Iron Cross still forms the basis of the modern Logo of the German Army (Logo des Heeres). At the same time the Reichsadler, a black Imperial Eagle, has been used on many German insignia including by Nazi Germany (1933–1945) and is still used as the coat of arms of Germany as well as by the current Federal Police.

When the Japanese Maritime Self-Defense Force was established in 1954, it adopted the Rising Sun Flag (Kyokujitsu-ki) as its ensign to show the nationality of its ships. It was approved by GHQ/SCAP. On 28 September 2018 an official of Japan's Ministry of Defense said that the South Korean navy's request lacks common sense and that they would not partake in a fleet review, since no country would follow such a request.[38] On October 6, 2018, JSDF Chief of Staff Katsutoshi Kawano said the Rising Sun Flag is the Maritime Self-Defense Force sailors' "pride" and that the MSDF would absolutely not go if they had to remove the flag.[14][39]

Korea did not object to Japan's adoption of the Rising Sun Flag for the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force in 1952, nor to the entry into Korean port carrying the flag on a warship at the 1998 and 2008 navy fleet review held in Korea.[40] Korean negative campaigns against the Rising Sun Flag began in 2011 when a Korean football player Ki Sung-yueng was accused of making a racial gesture, which he defended claiming he was annoyed at having seen a Rising Sun Flag in the stadium.[41] The next year in 2012, a word "war crime flag" was coined in South Korea to spread bad image of the flag.[42][43] An analysis indicates that Korean reactions to the Rising Sun Flag stem from the complicated emotion of excessive nationalism and nationalistic complex toward Japan.[44]

The Sankei Shimbun criticized South Korea's attitude toward the Rising Sun Flag, since even the United States, who was Japan's opponent during World War II, has not protested formally against the Rising Sun Flag.[45][46] The president of Sankei Shimbun Minagawa Hoshi said the corporate logo flag of the Rising Sun Flag design of the Asahi Shimbun, which is praised for being conscientious in Korea,[47] never had any such issues.[48]

In response to some allegations in Korea that the Rising Sun Flag is the same as the Nazi flag of Germany, the reporter Kisaragi Hayato of Searchina explained the origin of the Rising Sun Flag is the Sun and thus different. Furthermore, if South Korea insists that national symbols that Japan used to invade neighboring countries (in the past) should not be used at all, then Korea should also send objections to the use of for example the Union Jack which is the national flag of the United Kingdom and the tricolore Flag of France (Drapeau français), because these were traditionally used by the European countries during European colonialism, the first wave of European colonization (1415 to 1830 CE) and New Imperialism (late 19th and early 20th centuries).[49][50]

A Korean newspaper Maeil Business Newspaper raised a question that if Koreans accuse the Rising Sun Flag, why they are silent about the flags of China and North Korea which were opponents of the Korean War and killed hundreds of thousands of Korean people.[51]

Examples of the Rising Sun design in use

Art

One Hundred Views of Osaka, Three Great Bridges, ukiyo-e print by Utagawa Kunikazu, 1854. The composition of the morning sun rising behind the Nanhwa Three Bridge.

One Hundred Views of Osaka, Three Great Bridges, ukiyo-e print by Utagawa Kunikazu, 1854. The composition of the morning sun rising behind the Nanhwa Three Bridge. Wooden box label (Fujiyama Tea Co.) of Japanese tea (green tea) for export in the Meiji / Taisho period. Such a label was called orchid.

Wooden box label (Fujiyama Tea Co.) of Japanese tea (green tea) for export in the Meiji / Taisho period. Such a label was called orchid. From "Good and evil child's hand", " Kiyomori entrance" (Adachi Ginbo, 1885)

From "Good and evil child's hand", " Kiyomori entrance" (Adachi Ginbo, 1885) "Fugitoshi Fish Entering" (author unknown, 19th-century Edo period)

"Fugitoshi Fish Entering" (author unknown, 19th-century Edo period)- Japan raw silk pack sticker (in French and Japanese) (1880)

Products

- Tairyō-ki is a traditional Japanese fisherman's flag. Today it is used as a decorative flag on vessels and for festivals and events.

Flag of the Asahi Shimbun Company since 1889

Flag of the Asahi Shimbun Company since 1889 Asahi Gold Beer

Asahi Gold Beer Asahi Beer poster. The Asahi logo is on the bottle label (in 2013, at a pub in Higashiosaka city).

Asahi Beer poster. The Asahi logo is on the bottle label (in 2013, at a pub in Higashiosaka city).

Sports

- Japanese fans wave the Rising Sun Flag during a football match of Japan v.s. Bosnia and Herzegovina (30 January, 2008).

Japanese athlete Kinue Hitomi at the 1928 Summer Olympics

Japanese athlete Kinue Hitomi at the 1928 Summer Olympics

Japan Self-Defense Forces

Viewing march by JGSDF regiment vehicle troops with the flag of the Japan Self-Defense Forces

Viewing march by JGSDF regiment vehicle troops with the flag of the Japan Self-Defense Forces.jpg) Ground Self-Defense Force Utsunomiya gemstone site commemorative event with the Self-Defense Forces flag

Ground Self-Defense Force Utsunomiya gemstone site commemorative event with the Self-Defense Forces flag Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force members of the crew of JDS Kongō

Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force members of the crew of JDS Kongō_missile_is_launched_from_the_Japan_Maritime_Self-Defense_Force_destroyer_JS_Kirishima_(DD_174)%2C_succe.jpg) An SM-3 (Block 1A) missile is launched from the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force destroyer JS Kirishima

An SM-3 (Block 1A) missile is launched from the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force destroyer JS Kirishima_leads_a_formation_of_U.S._Navy_and_Japan_Maritime_Self-Defense_Force_sips_during_Annual_Exercise_(ANNUALEX_21G).jpg)

United States military

Emblem of United States Fleet Activities Sasebo

Emblem of United States Fleet Activities Sasebo Patch of Strike Fighter Squadron 94

Patch of Strike Fighter Squadron 94 Emblem of U.S. Army Aviation Battalion Japan

Emblem of U.S. Army Aviation Battalion Japan The mural painted on a wall at Misawa Air Base, Japan

The mural painted on a wall at Misawa Air Base, Japan- Former insignia of Strike Fighter Squadron 192

- Joint Helmet Mounted Cueing System with patches of the 14th Fighter Squadron

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Rising Sun Flag of Japan. |

- Flag of Japan

- List of Japanese flags

- List of Japanese municipal flags

- National symbols of Japan

- Imperial Seal of Japan

- Tairyō-bata

Other flags with sun rays

Flag of the Russian Air Force

Flag of the Russian Air Force Flag of Donetsk Oblast, Ukraine

Flag of Donetsk Oblast, Ukraine

Flag of the Karen National Liberation Army

Flag of the Karen National Liberation Army

Korean Unification Church Flag

Korean Unification Church Flag Flag of the Belarusian Air Force

Flag of the Belarusian Air Force Flag of the Kazakhstan Air Force

Flag of the Kazakhstan Air Force Flag of the Turkmenistan Air Forces

Flag of the Turkmenistan Air Forces

References

- 1 2 3 4 "Japanese Symbols". Japan Visitor/Japan Tourist Info. Retrieved October 9, 2014.

- ↑ "船舶旗について" (PDF). Kobe University Repository:Kernel. Retrieved October 18, 2014.

- ↑ Dyer 1909, p. 24

- ↑ Edgington 2003, pp. 123–124

- ↑ Itoh 2003, p. 205

- 1 2 Designer Idezaka (September 9, 2013). "浮世絵と西洋の出合い 戦前の輸出茶ラベルの魅力 (Ukiyo-e and Western encounter The charm of the exported tea label before the war)". Nikkei Style. Retrieved October 4, 2018.

|archive-url=is malformed: save command (help) - ↑ "Where does the name Japan come from?". Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- ↑ Piggott, Joan R. (1997). The emergence of Japanese kingship. Stanford University Press. pp. 143–144. ISBN 978-0-8047-2832-4.

- 1 2 3 Government of Japan. 自衛隊法施行令 [Self-Defense Forces Law Enforcement Order]; 1954-06-30 [Retrieved 2008-01-25]. (in Japanese).

- ↑ "海軍旗の由来". kwn.ne.jp. Retrieved 6 October 2011.

- ↑ Phil Nelson; various. "Japanese military flags". Flags Of The World. Flagspot.

- 1 2 "Asahi Beer New Design". Japan Visitor Blog. December 12, 2011.

- ↑ "A great decade for Japan". FIFATV. 2012-12-18.

- 1 2 "Japan to skip S. Korea fleet event over 'rising sun' flag". The Asahi Shimbun. October 6, 2018. Archived from the original on 2018-10-06. Retrieved October 7, 2018.

- ↑ "World: Asia-Pacific Reprise for Japan's anthem". BBC News. August 15, 1999.

- 1 2 Radhika Seth (August 14, 2012). "Courting Controversy: Olympic Uniform resembled rising sun flag!". Japan Daily Press. Archived from the original on 2012-08-17. Retrieved September 18, 2012.

- 1 2 "Korean lawmakers adopt resolution calling on Japan not to use rising sun flag". Korea Herald. August 29, 2012. Retrieved September 18, 2012.

- 1 2 "Japanese "Rising Sun Flag" Sparking More Tension between Korea and Japan". Business Korea. August 9, 2013.

- 1 2 Naoto Okamura (August 8, 2008). "Japan fans warned not to fly naval flag". Reuters.

- ↑ Taylor, Adam (2015-06-27). "Japan has a flag problem, too". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2017-10-06.

- ↑ "US Vets". newsweek. ISSN 0190-8286.

- ↑ Bill McMichael (August 2, 2011). "That Flag". Navy Times Scoop Deck.

- ↑ Tom Hester (November 3, 2008). "Trenton's 'Lady Victory' monument honors W W II vets". NJ.com.

- ↑ Martin Kidston (April 26, 2014). "Hellgate High senior will escort WWII veterans on final Big Sky Honor Flight". Missoulian.

- ↑ "S. Korea renews call for Japan to remove 'rising sun' flag".

- ↑ "일본 함정, 욱일기 달고 진해항 입항" [Japanese warships arrived the Jinhae port carrying the rising flag]. May 25, 2016.

- ↑ "독일 '나치'는 엄벌하면서 일본 '욱일기'는 대놓고 봐주는 유럽 국가들" [European countries openly allow the "Rising sun flag" while punishing the German "Nazi" (flag)]. Insight. July 15, 2018.

- ↑ "Nazi flag vs. Rising Sun Flag". September 5, 2017.

- ↑ Beer, Robert (1 January 2003). "The Handbook of Tibetan Buddhist Symbols". Serindia Publications, Inc. – via Google Books.

- ↑ Swastika: SYMBOL, Encyclopædia Britannica (2017)

- ↑ Bruce M. Sullivan (2001). The A to Z of Hinduism. Scarecrow Press. p. 216. ISBN 978-1-4616-7189-3.

- ↑ Adrian Snodgrass (1992). The Symbolism of the Stupa. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 82–83. ISBN 978-81-208-0781-5.

- ↑ Norman C. McClelland (2010). Encyclopedia of Reincarnation and Karma. McFarland. pp. 263–264. ISBN 978-0-7864-5675-8.

- ↑ (in German) Herzfeld, Andreas (June 2001). "Einige unbekannte Flaggenänderungen 1933–1945". Der Flaggenkurier (in German). Hennigsdorf: Deutsche Gesellschaft für Flaggenkunde (13): 17–23. Archived from the original on 2011-07-17.

- ↑ Consulate-General of Japan in San Francisco. Basic / General Information on Japan; 2008-01-01 [archived 2012-12-11; Retrieved 2009-11-19].

- ↑ "Dictionary of Vexillology: B (Banner Roll - Bauceant)". Dictionary of Vexillology. FOTW Flags Of The World. Archived from the original on 24 October 2012. Retrieved 19 August 2012. ; etymologizing "balk cross" in "Dictionary of Vexillology: B (Backing - Banner of Victory)". Dictionary of Vexillology. FOTW Flags Of The World. Retrieved 19 August 2012. . C.f. th erroneous rendition as "Balkan Cross" in John Cochrane, Stuart Elliott, Military Aircraft Insignia of the World, Naval Institute Press, 1998, p. 50.

- ↑ Takeda, Hajimu (September 28, 2018). "S. Korea wants MSDF to lower 'kyokujitsuki' flag in review". The Asahi Shimbun. Archived from the original on 2018-10-05. Retrieved October 4, 2018.

- ↑ https://www.scmp.com/news/asia/east-asia/article/2167441/japan-pulls-out-south-korea-naval-drills-over-demands-it-remove?utm_medium=Social&utm_source=Facebook#Echobox=1538983837

- ↑ "[특파원 칼럼] 대일외교, '감정'보다 '사실' 앞세워야" [Foreign diplomacy, Put forward "fact" rather than "emotion"]. Korea Economic Daily. October 12, 2018.

- ↑ "「旭日旗」問題の契機はサッカー・アジア杯 奥薗静岡県立大准教授" [Rising Sun Flag controversy began at an Asian Cup Football match - Associate Professor of the University of Shizuoka Okuzono]. Sankei Shimbun. October 5, 2018.

- ↑ "[Why] 욱일기 때문에 불참통보한 일본군함, 우린 왜 지금 더 분노하나" [[Why] The Japanese warship conveyed an absence. Why are we angry now?]. The Chosun Ilbo. October 6, 2018.

- ↑ "[팩트체크] 욱일기는 전범기? '전범기'는 없다" [[Fact check] Rising Sun Flag is war crime flag? There is no "war crime flag"]. News True or Fake. October 6, 2018.

In the picture above, the word "war crime flag" was first used in Korea in August 2012.

- ↑ "햄버거 포장도 '욱일기 딱지'…도 넘는 반일정서" [Hamburger wrap "Rising sun flag" ... excessive anti-Japan sentiment]. Korea Economic Daily. June 6, 2017.

툭하면 터지는 욱일기 논란은 과도한 민족주의와 민족주의적 콤플렉스라는 복잡한 정서가 출발점이다 ... 늘 그렇듯 욱일기 논란도 일본에 대해 갖고 있는 일종의 콤플렉스 기제의 작동

- ↑ 韓国の反日から旭日旗の名誉を守れ (第三段 国際社会は受け入れ) 産経新聞 2013年8月3日

- ↑ "日本の艦艇、旭日旗を掲げて韓国に入港し物議=韓国ネット「...|". レコードチャイナ. Retrieved 2018-07-17.

- ↑ "日우파기자가 밝힌 우파들의 본심" [Real intention of the rightist revealed by a Japanese rightist reporter]. The Chosun Ilbo.

- ↑ 皆川豪志. "なぜ韓国人は、朝日の社旗に怒らないのか,繰り返されるマッチポンプ". iRONNA. 産経デジタル. Retrieved 2018-05-18.

- ↑ 韓国世論「旭日旗とナチス党旗を同一視」の大いなる誤解 サーチナ 2013年4月16日

- ↑

Compare:

Louis, William Roger (2006). "32: Robinson and Gallagher and Their Critics". Ends of British Imperialism: The Scramble for Empire, Suez, and Decolonization. London: I.B.Tauris. p. 910. ISBN 9781845113476. Retrieved 2017-08-10.

[...] the concept of the 'new imperialism' espoused by such diverse writers as John A. Hobson, V. I. Lenin, Leonard Woolf, Parker T, Moon, Robert L. Schuyler, and William L. Langer. Those students of imperialism, whatever their purpose in writing, all saw a fundamental difference between the imperialist impulses of the mid- and late-Victorian eras. Langer perhaps best summarized the importance of making the distinction of late-nineteenth-century imperialism when he wrote in 1935: '[...] this period will stand out as the crucial epoch during which the nations of the western world extended their political, economic and cultural influence over Africa and over large parts of Asia ... in the larger sense the story is more than the story of rivalry between European imperialisms; it is the story of European aggression and advance in the non-European parts of the world.'

- ↑ "[기고] '욱일기=전범기' 논란의 그늘" [[Contribution] The shadows of controversy,]. Maeil Business Newspaper. October 9, 2018.