Revolutions of 1917–1923

| Revolutions of 1917–1923 | |

|---|---|

| Part of the aftermath of World War I | |

_(14595451159).jpg) | |

| Date | 8 March 1917 – c. 16 June 1923 |

| Location | Worldwide (mainly in Europe and Asia) |

| Caused by |

|

| Goals | |

| Resulted in | |

The Revolutions of 1917–1923 were a period of political unrest and revolts around the world inspired by the success of the Russian Revolution and the disorder created by the aftermath of World War I. The uprisings were mainly socialist or anti-colonial in nature and were mostly short-lived, failing to have a long-term impact.[1] Out of all the revolutionary activity of the era, the revolutionary wave of 1917–1923 mainly refers to the unrest caused by World War I in Europe.[2]

Communist revolutions in Europe

Russia

In war-torn Imperial Russia, the liberal February Revolution toppled the monarchy. It was unstable and the Bolsheviks seized power in the October Revolution. The ascendant communist party soon withdrew from the war with some territorial concessions by the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk. It then battled its political rivals in the Russian Civil War, including invading forces from the Allied Powers. In response to Lenin, the Bolshevik Party and the emerging Soviet Union, anti-communists from a broad assortment of ideological factions fought against them, particularly through the counter-revolutionary White movement and the peasant Green Army, the various nationalist movements in Ukraine after the Russian Revolution and other would-be new states like those in Soviet Transcaucasia and Soviet Central Asia, through the anarchist-inspired Third Russian Revolution and Tambov Rebellion.[3]

By 1921, due to exhaustion, the collapse of transportation and markets, and threats of starvation, even dissident elements of the Red Army itself were in revolt against the communist state, as shown by the Kronstadt rebellion. However, the multiple anti-Bolshevik forces were uncoordinated and disorganized, and in every case operated on the periphery. The Red Army, operating at the center, defeated them one by one and regained control. The complete failure of Comintern-inspired revolutions was a sobering experience in Moscow, and the Bolsheviks moved from world revolution to the theme of socialism in one country, Russia. Lenin moved to open trade relations with Britain, Germany, and other major countries. Most dramatically, in 1921, Lenin introduced a sort of small-scale capitalism with his New Economic Policy (or NEP). In this process of revolution and counter-revolution the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) was officially born in 1922.[4]

Western Europe

The Leninist victories also inspired a surge by the world Communist movement: the larger German Revolution and its offspring, like the Bavarian Soviet Republic, as well as the neighboring Hungarian Revolution, and the Biennio Rosso in Italy in addition to various smaller uprisings, protests and strikes, all proved abortive.

The Bolsheviks sought to coordinate this new wave of revolution in the Soviet-led Communist International, while new communist parties separated from their former socialist organizations and the older, more moderate Second International. Despite ambitions for world revolution, the far-flung Comintern movement had more setbacks than successes through the next generation, and it was abolished in 1943.[5] After the Second World War when the Red Army occupied most of Eastern Europe, Communists would come to power in the Baltic states, Poland, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Romania, Bulgaria, and East Germany.[6]

Non-Communist revolutions

Ireland

In Ireland, then part of the United Kingdom, the nationalist Easter Rising of 1916 anticipated the Irish War of Independence (1919–1921) within the same historical period as this first wave of communist revolution. The Irish republican movement of the time was predominantly nationalist and populist, and although it had left-wing positions and included socialists and communists, it was not Communist. The Irish and Soviet Russian Republics nevertheless found common ground in their opposition to British interests, and established a trading relationship.

Mexico

The same was true of the Mexican Revolution (1910–1920), which had broken out in 1910 but had devolved into factional fighting among the rebels by 1915, as the more radical forces of Emiliano Zapata and Pancho Villa lost ground to the more conservative "Sonoran oligarchy" and its Constitutional Army. The Felicistas, the last major group of counterrevolutionaries, abandoned their armed campaign in 1920, and the internecine power struggles abated for a time after revolutionary General Álvaro Obregón had bribed or slain his former allies and rivals alike, but the following decade witnessed the assassination of Obregon and several others, abortive military coup attempts and a massive right-wing uprising, the Cristero War, due to religious persecution of Roman Catholics.

Malta

The Sette Giugno of 1919 was a revolt characterised by a series of riots and protests by the Maltese population, initially as a reaction to the rise in the cost of living in the aftermath of World War I, and the sacking of hundreds of workers from the dockyard. This coincided with popular demands for self-government, which resulted in a National Assembly being formed in Valletta at the same time of the riots. This dramatically boosted the uprising, as many people headed to Valletta to show their support for the Assembly. This led to the British forces firing into the crowd, killing four local men. The cost of living increased dramatically after the war. Imports were limited, and as food became scarce prices rose; this made the fortune of farmers and merchants with surpluses to trade.

Egypt

The Egyptian Revolution of 1919 was a countrywide revolution against the British occupation of Egypt and Sudan. It was carried out by Egyptians and Sudanese from different walks of life in the wake of the British-ordered exile of revolutionary leader Saad Zaghloul, and other members of the Wafd Party in 1919. The revolution led to Britain's recognition of Egyptian independence in 1922, and the implementation of a new constitution in 1923. Britain, however, continued in control of what was renamed the Kingdom of Egypt. British guided the king and retained control of the Canal Zone, Sudan and Egypt's external and military affairs. King Fuad died in 1936 and Farouk inherited the throne at the age of sixteen. Alarmed by the Second Italo-Abyssinian War when Italy invaded Ethiopia, he signed the Anglo-Egyptian Treaty, requiring Britain to withdraw all troops from Egypt by 1949, except at the Suez Canal. During World War II, British troops used Egypt as a major base for its operations throughout the region. British troops were withdrawn to the Suez Canal area in 1947, but nationalist, anti-British feelings continued to grow after the war.[7]

Communist revolutions that started 1917–24

- Russian Revolution (1917)

- Free Territory (1918)

- Aster Revolution (1918)

- Red Week (Netherlands) (1918)

- Finnish Civil War (1918)

- Political violence in Germany (1918–33)

- German Revolution (1918–1919)

- People's State of Bavaria (1918–1919)

- Bremen Soviet Republic (1919)

- Bavarian Council Republic (1919)

- Ruhr Uprising (1920)

- March Action (1921)

- Hamburg Uprising (1923)

- German October (1923)

- German Revolution (1918–1919)

- Brussels Soldiers' Council (1918)

- Revolutions and interventions in Hungary (1918–1920)

- Slovak Soviet Republic (1919)

- Fascist and anti-Fascist violence in Italy (1919–1926)

- Biennio Rosso (1919–20)

- Labin Republic (1921)

- Tragic Week (1919)

- Limerick Soviet (1919)

- Canadian Labour Revolt (1919)[8]

- Persian Socialist Soviet Republic (1920–1921)

- Georgian coup attempt (1920)

- Provisional Polish Revolutionary Committee (1920)

- Patagonia Rebelde (1920-22)

- Mongolian Revolution of 1921

- Rand Rebellion (1921–22)

- September Uprising (Bulgaria) (1923)

- August Uprising (Georgia) (1924)

- Tatarbunary uprising (1924)

- Estonian coup d'état attempt ("Tallinn Uprising") (1924)

- Chinese Civil War (1927–1936/1950)

Left-wing uprisings against the USSR

- Left SR uprising (1918)

- Left-wing uprisings against the Bolsheviks (1918–1922)

- Revolutionary Insurrectionary Army of Ukraine (1918–1922)

- Tambov Rebellion (1920–1921)

- Kronstadt Rebellion (1921)

Counter-revolutions against USSR that started 1917-1921

- White movement (1917–1923)

- Kuban People's Republic (1918–1920)

- Mountainous Republic of the Northern Caucasus (1917–1920)

- First Republic of Armenia (1918–1920)

- Democratic Republic of Georgia (1918–1921)

- Azerbaijan Democratic Republic (1918–1920)

- Bulgarian coup d'état (1923)

Soviet counter-counter-revolutions that started 1918–1919

- Russian Civil War (1917–1923)

- Red Terror (1918)

- Polish–Soviet War (1919–1921)

- Tuvan coup d'état (1929)

Other

- Finnish Civil War (1918)

- Greater Poland Uprising (1918–19)

- Sejny Uprising (1919)

- Silesian Uprisings (1919–1921)

- Turkish War of Independence (1919–1923)

- Iraqi revolt against the British (1920)

- Uprising in West Hungary (1921)

- Battle of Blair Mountain (1922)

See also

References

- ↑ Motadel, David (April 4, 2011). "Waves of Revolution". History Today. Retrieved May 5, 2015.

- ↑ Schmitt, Hans. "Neutral Europe Between War and Revolution, 1917-23". Retrieved May 5, 2016.

- ↑ Abraham Ascher, //The Russian Revolution: A Beginner's Guide (Oneworld Publications, 2014)

- ↑ Rex A. Wade, "The Revolution at One Hundred: Issues and Trends in the English Language Historiography of the Russian Revolution of 1917." Journal of Modern Russian History and Historiography 9.1 (2016): 9-38.

- ↑ Kevin McDermott and Jeremy Agnew, The Comintern: A History of International Communism from Lenin to Stalin (Macmillan, 1996).

- ↑ Robert Service, Comrades!: A History of World Communism (2010).

- ↑ P.J. Vatikiotis, The History of Modern Egypt (4th ed., 1992).

- ↑ Kealey, Gregory (1984). "1919: The Canadian Labour Revolt". Journal of Canadian Labour Studies. Archived from the original on October 22, 2017.

Related links

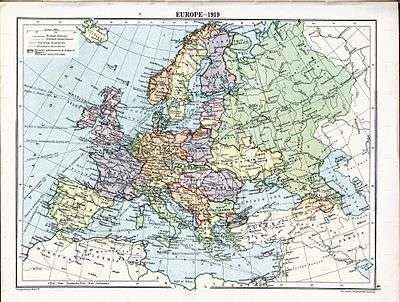

- Maps of Europe showing the Revolutions of 1917–23 at omniatlas.com