Religious skepticism

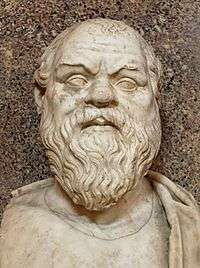

Religious skepticism is a type of skepticism relating to religion. Religious skeptics question religious authority and are not necessarily anti-religious but skeptical of specific or all religious beliefs and/or practices. Socrates was one of the most prominent and first religious skeptics of whom there are records; he questioned the legitimacy of the beliefs of his time in the existence of the Greek gods. Religious skepticism is not the same as atheism or agnosticism and some religious skeptics are deists.

Overview

The word skeptic (sometimes sceptic) is derived from the middle French sceptique or the Latin scepticus, literally "sect of the sceptics". Its origin is in the Greek skeptikos, meaning inquiring, reflective or one that doubts.[1] As such, religious skepticism generally refers to doubting or questioning something about religion. Although, as noted by Schellenberg the term is sometimes more generally applied to anyone that has a negative view of religion.[2]

The earliest beginnings of religious skepticism can be traced back to Xenophanes. He critiqued popular religion of his time, particularly false conceptions of the divine that are a byproduct of the human propensity to anthropomorphize deities. He took the scripture of his time to task for painting the gods in a negative light and promoted a more rational view of religion. He was very critical of religious people privileging their belief system over others without sound reason[3][4]

The majority of skeptics are agnostics and atheists but there are also a number of religious people that are skeptical of religion.[5] The religious are generally skeptical about claims of other religions, at least when the two denominations conflict concerning some stated belief. Some philosophers put forth the sheer diversity of religion as a justification for skepticism by theists and non-theists alike.[6] Theists are also generally skeptical of the claims put forth by atheists.[7]

Michael Shermer wrote that religious skepticism is a process for discovering the truth rather than general non-acceptance. For this reason a religious skeptic might believe that Jesus existed while questioning claims that he was the messiah or performed miracles (see historicity of Jesus). Thomas Jefferson's The Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth, a literal cut and paste of the New Testament that removes anything supernatural, is a prominent example.

Modern religious skepticism

The term has morphed into one that typically emphasizes scientific and historical methods of evidence. There are some skeptics that question whether religion is a viable topic for criticism given that it doesn't require proof for belief. Others, however, insist it is as much as any other knowledge. Especially when it makes claims that contradict those made by science.[8][9]

There has been much work since the late 20th century by philosophers such as Schellenburg and Moser and both have written numerous books pertaining to the topic.[10][11] Much of their work has focused on defining what religion is and specifically what people are skeptical of about it.[12][2] The work of others have argued for the viability of religious skepticism by appeal to higher-order evidence (evidence about our evidence and our capacities for evaluation),[13] what some call meta-evidence.[14]

There are still echos of early Greek skepticism in the way some current thinkers question the intellectual viability of belief in the divine.[15]

In modern times there is a certain amount of mistrust and lack of acceptance of religious skeptics, particularly towards those that are also atheists.[16][17][18] This is coupled with concerns many skeptics have about the government in countries, such as the U.S.A., where separation of church and state are central tenants.[19]

Selected historical occurrences

Socrates was raised in polytheistic society in which the gods were not omnipotent and required sacrifice and ritual. Socrates' conception of the divine was that they always benevolent, truthful, authoritative, and wise. Divinity was to operate within the standards of rationality.[20] This critique ultimately resulted in his trial for impiety and corruption as documented in The Apology.

The historian Will Durant writes that Plato was "as skeptical of atheism as of any other dogma."[21][4]

Democritus was the father of Materialism and there is no trace of a belief in afterlife in his work. Specifically in Those in Hades he refers to constituents of the soul as atoms that dissolve upon death.[22]

In De Natura Deorum the Roman statesman Cicero calls into question the character of the gods, whether or not they participate in earthly affairs, and questions their existence. This a significant evolution from his earlier writings wherein he was more accommodating to religion[23]

In the poem De rerum natura Lucretius introduces epicurean philosophy to the Romans and proclaims that the universe operates according to physical principles and guided by fortuna, or chance, instead of the Roman gods.[24]

Thomas Hobbes took positions that strongly disagreed with church teachings. He argued repeatedly that there are no incorporeal substances, and that all things, even God, heaven, and hell are corporeal, matter in motion. He argued that "though Scripture acknowledge spirits, yet doth it nowhere say, that they are incorporeal, meaning thereby without dimensions and quantity".[25]

Voltaire, although himself a deist, was a forceful critic of religion and advocated for acceptance of all religions as well as separation of church and state.[26]

See also

References

- ↑ "skeptic (n.)". etymonline.com. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- 1 2 Schellenberg, J. L. "Religious Skepticism from Skepticism: From Antiquity to the Present" (PDF). Bloomsbury. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- ↑ "Xenophanes". www.iep.utm.edu. Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 10 May 2018.

- 1 2 Vogt, Katja. "Ancient Skepticism". stanford.edu. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 10 May 2018.

- ↑ Sturgess, Kylie (June 2009). "The Deist Skeptic— Not a Contradiction". Skeptical Inquirer. 19 (2). Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- ↑ Schellenberg, J. L. "Religious Diversity and Religious Skepticism from The Blackwell Companion to Religious Diversity". philarchive. Oxford: Wiley Blackwell. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- ↑ Mann, Daniel. "Skeptical of Atheism". Apologetics for Today. Retrieved 2 December 2013.

- ↑ Novella, Steven. "Apr 05 2010 Skepticism and Religion – Again". theness. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- ↑ Kurtz, Paul (August 1999). "Should Skeptical Inquiry Be Applied to Religion?". Skeptical Inquirer. 23 (4). Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- ↑ "J. L. Schellenberg". cornellpress.cornell.edu. Cornell University Press. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- ↑ "Books by Paul K. Moser". goodreads.com. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- ↑ Moser, P. "Religious Skepticism from The Oxford Handbook of Skepticism" (PDF). Oxford Univ. Press. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- ↑ King, N. L. (March 2016). Religious Skepticism and Higher-Order Evidence from Oxford Studies in Philosophy of Religion: Volume 7. Oxford Scholarship Online. ISBN 9780198757702. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- ↑ Wykstra, S. J. (2011). "Facing MECCA Ultimism, Religious Skepticism, and Schellenberg's "Meta-Evidential Condition Constraining Assent"". Philo. 14 (1): 85–100. doi:10.5840/Philo20111418. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- ↑ Penner, Myron A. (2014). "Religious Skepticism". Toronto Journal of Theology. 30 (1): 111–129. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- ↑ Hughes, J.; Grossman, I.; Cohen, A. B. (8 September 2015). "Tolerating the "doubting Thomas": how centrality of religious beliefs vs. practices influences prejudice against atheists". Frontiers in Psychology. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01352. Retrieved 10 May 2018.

- ↑ Zuckerman, P. (26 November 2009). "Atheism, Secularity, and Well‐Being: How the Findings of Social Science Counter Negative Stereotypes and Assumptions". Sociology Compass. 3 (3): 949–971. doi:10.1111/j.1751-9020.2009.00247.x. Retrieved 10 May 2018.

- ↑ Edgell, P.; Gerteis, J,; Hartmann, D. (1 April 2006). "Atheists As "Other": Moral Boundaries and Cultural Membership in American Society". American Sociological Review. 71 (2): 211–234. doi:10.1177/000312240607100203. Retrieved 10 May 2018.

- ↑ Coskun, Deniz. "Religious Skepticism, Cambridge Platonism, and Disestablishment". hein online. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- ↑ "Socrates". www.iep.utm.edu. Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 10 May 2018.

- ↑ Durant, Will (1944). Caesar and Christ: The Story of Civilization. Simon & Schuster. p. 164.

- ↑ Ferwerda, R. (1972). "Democritus and Plato". Mnemosyne. 25 (4): 340. JSTOR 4430143.

- ↑ Verhine, Eric C. (2008). "1". THE VICTORIOUS WISDOM OF SIMONIDES: CICERO’S JUSTIFICATION OF ACADEMIC SKEPTICISM IN DE NATURA DEORUM AND DE DIVINATIONE (PDF) (Master of Arts). p. 2. Retrieved 10 May 2018.

- ↑ In particular, De rerum natura 5.107 (fortuna gubernans, "guiding chance" or "fortune at the helm"): see Monica R. Gale, Myth and Poetry in Lucretius (Cambridge University Press, 1994, 1996 reprint), pp. 213, 223–224 online and Lucretius (Oxford University Press, 2007), p. 238 online.

- ↑ Lawler, J. M. (2006). Matter and Spirit: The Battle of Metaphysics in Modern Western Philosophy Before Kant. University Rochester Press. p. 19. ISBN 9781580462211. Retrieved 10 May 2018.

- ↑ Pomeau, R. H. "Voltaire". britannica.com. Encyclopedia Brittanica. Retrieved 10 May 2018.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Religious skepticism |