Asylum in Australia

Asylum in Australia is governed by statutes and Government policies which seek to implement Australia's obligations under the Convention relating to the Status of Refugees, to which Australia is a party. Thousands of refugees have sought asylum in Australia over the past decade,[1] with the main forces driving movement being war, civil unrest and persecution.[2] The annual refugee quota is currently 20,000 people.[3] From 1945 to the early 1990s, more than half a million refugees and other displaced persons were accepted into Australia.[4]

Historically, most asylum seekers arrived by plane. However, there was an increasing number of asylum seekers arriving by boat in the late 2000s and early 2010s, which was met with some public disapproval.[5] In 2011-2012, asylum seekers arriving by boat outnumbered those arriving by plane for the first time.[6][7][8] Three waves of asylum seekers arriving by boat have been identified: Vietnamese between 1976 and 1981; Indochinese asylum seekers from 1989 to 1998; and people of Middle East origin, and the use of people smugglers, from 1999.[5]

The visa policy of the current government is to detain persons entering or being in Australia without a valid visa until those persons can be returned to their home country. Australia is the only country in the world with a policy of mandatory detention and offshore processing of asylum seekers who arrive without a valid visa.[9][10]

Asylum policy is a contentious wedge issue in Australian politics, with the two major political parties in Australia arguing that the issue is a border control problem and one concerning the safety of those attempting to come to Australia by boat.

Claims processing

A compliance interview, often done with the assistance of an interpreter, is one of the first steps taken by immigration officers to determine if a person is making a valid claim of asylum.[11] If a valid fear of persecution is expressed a formal application for refugee status is undertaken. If permission to stay in Australia is not granted they must be removed as soon as possible.[12] However, under the notion of complementary protection, an applicant who is not deemed to be a refugee may still be permitted to remain in Australia [13] Complementary protection applies when an applicant/s would face a real risk of; arbitrary deprivation of life; the death penalty; torture; cruel or inhuman treatment or punishment; degrading treatment or punishment.[13] It does not apply when there is no real risk of significant harm, namely when an applicant can safely relocate to another part of the country, or an authority within the country can provide protection.[13]

People who arrived by boat on or after 13 August 2012 are not able to propose that their immediate family members also gain entry to Australia.[14]

A new "fast track" assessment scheme was introduced in 2014 via the Migration and Maritime Powers Legislation Amendment (Resolving the Asylum Legacy Caseload) Bill 2014 . The definition of a fast track applicant was narrowed further by Immigration Minister Peter Dutton in an amendment to the definition under the "Migration Act 1958", which changed the date of arrival requirement from January 2012 to August 2012 for parents whose children wished to be put classified as fast track applicants.[15]

Statistics

The annual refugee quota is currently 20,000 people.[3] According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Australia was ranked 47th out of 198 countries in the world in terms of the number of refugees hosted between 2005 and 2009, out of those countries who host refugees.[16] In 2012, the Refugee Council of Australia ranked Australia 22nd on a per capita basis in a list of countries that accept refugees.[17] The Council found that in terms of resettlement (as opposed to "receiving") asylum seekers, Australia ranks 2nd in the world overall, 3rd per capita and 3rd as a proportion of GDP.[18]

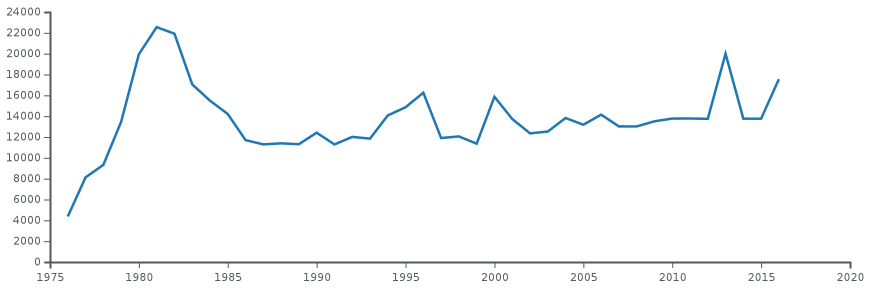

Australia's total refugee and humanitarian intake has remained relatively constant since the mid-1980s:[19]

The rate of arrivals by boat, the most controversial aspect of Australia's refugee policy, has been exceptionally volatile. It reached a peak of 20,587 people in 2013 (excluding crew), before falling again to zero two years later:[20]

History

Refugees and World War II: 1930s

In the 1930s more than 7,000 refugees from Nazi Germany were accepted into Australia.[21] In the eight years after the end of World War II almost 200,000 European refugees settled in Australia. Australia was reluctant to recognise a general "right of asylum" for refugees when the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was being drafted.[22] The White Australia policy was responsible for the exclusion of Asians from migration to Australia until 1973.[23]

Vietnamese boat people: 1970s

The first recorded instance of asylum seekers arriving in Australia via unauthorised boat occurred in April 1976. Fleeing South Vietnam after the Communist Party victory of 1974, an estimated 2,000 "Vietnamese boat people" followed from 1976–1982. The sporadic arrival of unauthorised boats was a cause of concern for the Australian people.[24] The initial controversy regarding asylum seekers in Australia was mostly because of family reunions.[23] Employment and security concerns were also raised with the Waterside Workers Federation calling for strikes on the matter.[5] This led to the first detention of boat people. In response, the government of Malcolm Fraser authorized the immigration of more than 50,000 Vietnamese from Indian Ocean refugee camps. At the time, the "open door" immigration policy enjoyed bipartisan support.[24]

Mandatory detention: the 1990s

During the early 1990s, asylum seekers from Cambodia began to arrive in Australia. In response, the government of Paul Keating instituted a mandatory detention policy aimed at deterring refugees.[24] Under mandatory detention, anyone who enters the Australian migration zone without a visa is placed in a holding facility while security and health checks are performed. Additionally, the validity of the person's claim to asylum is assessed by the Department of Immigration and Citizenship.

In 1990, a number of asylum seekers arrived from Somalia without documentation. They were detained at Villawood Immigration Detention Centre for 18 months without any progress on their status. Some began a hunger strike in response to the prolonged detention. Eventually, all were determined to be genuine refugees.[25]

In the mid-1990s, numerous boats carrying Chinese and Sino-Vietnamese refugees were returned to their place of origin after asylum claims were denied. The rapid repatriations meant that many citizens were unaware of the refugees.[24] During this period a refugee from Indonesia was detained for 707 days before being granted refugee status.[25]

In 1999, Middle Eastern immigrants fleeing from oppressive regimes in Afghanistan, Iran and Iraq began to arrive in large numbers.[24] The government of John Howard extended the time they spent in mandatory detention and introduced temporary protection visas for boat arrivals.[10] The deterrents did little to stop immigrants; roughly 12,000 asylum seekers reached Australia from 1999 to 2001.[24]

Pacific Solution: 2001–2007

In August 2001, a Norwegian tanker, the Tampa, picked up 438 people whose vessel was sinking off the coast of Indonesia. According to the captain, he tried to return the Afghan refugees to Indonesia, but they threatened to throw themselves overboard if he did so. Consequently, he agreed to take them to Christmas Island. Howard's government refused to allow the boat to land, saying it was a matter for Norway and Indonesia to work out amongst themselves. Neither made a move, creating a three way diplomatic standoff which became known as the Tampa Affair. Australia seized control of the ship, drawing international criticism but strong support in the country. After ten days, Australia struck a deal with New Zealand and Nauru to have those nations temporarily host the refugees while Australia processed their asylum claims.[26] Following the September 11 attacks in the US, anti-Muslim rhetoric increased in Australia, as Muslims were the primary asylum seekers at the time.[23]

Following the Tampa Affair, the Commonwealth Migration Act (1958) was amended by Howard's government in September 2001.[28] The amendments, which became known as the Pacific Solution, prevented refugees landing on Christmas Island or Ashmore Reef from seeking asylum.[24] Instead, they were redirected to nearby island nations such as Papua New Guinea and Nauru. There, refugees had to undergo a lengthy asylum process before they could immigrate to Australia.[1] At the time, the minority Labor Party opposed the policy. In 2003, Julia Gillard promised that Labor would end the Pacific Solution "because it is costly, unsustainable and wrong as a matter of principle".[29]

The Pacific Solution was intended to remove the incentive for refugees to come to Australia. While detained offshore, asylum-seekers under the Pacific Solution were denied access to Australian lawyers and to protection under Australian law.[10]

.jpg)

The policy was highly criticised by human rights groups.[1] The primary concern was that abusive process could potentially develop in remote locations.[30] In 2002, the arrivals dropped from 5,516 the previous year to 1.[5] From 2001 to 2007, fewer than 300 asylum seekers arrived.[24] The program cost Australia more than AU$1 billion during that period.[31] In July 2005, Australia ceased the practice of mandatory detention of children.[30]

End of offshore processing: 2007–2012

In 2007, the Labor Party under Prime Minister Kevin Rudd abandoned the Pacific Solution, installing a more liberal asylum policy.[1] Rudd's government pledged to settle all asylum claims within three months and closed the Nauru detention facility.[24] The Rudd government abolished temporary protection visas in 2008.[10] Only 45 of the 1,637 asylum seekers detained in Nauru were found not to be refugees.[2]

Over the next few years the number of asylum seekers arriving in the country increased substantially.[1] In 2008, there were 161 immigrants under asylum laws; in 2009, claims jumped to 2,800.[1][24] The issue quickly became a political problem for Rudd. He claimed it was a change in the international political environment that caused the increase, not the abandonment of the Pacific Solution. When that idea failed to be accepted, he proposed what became known as the Indonesian Solution. Under the plan, Indonesia would receive financial aid and intelligence in exchange for cracking down on the people smugglers that transported the asylum seekers. In October 2009, the customs boat Oceanic Viking picked up shipwrecked asylum seekers and attempted to return them to Indonesia, as agreed. However, the attempts to unload the refugees failed and Labor's poll numbers dropped significantly.[24]

In December 2010, a boat of refugees sank, killing 48 people.[32]

| Australia's refugee and humanitarian program | |

|---|---|

| Year | Grants |

| 2006–07 | 13,017 |

| 2007–08 | 13,014 |

| 2008–09 | 13,507 |

| 2009–10 | 13,770 |

| 2010–11 | 13,799 |

| 2011–12 | 13,759 |

| 2012–13 | 20,019 |

| Source: Department of Immigration and Citizenship[33] | |

Ahead of the 2010 election, Tony Abbott campaigned on the asylum issue, and with Rudd refusing to engage with him in "a race to the bottom", polls showed the public strongly favouring Abbott's anti-asylum views. By this time, Rudd was struggling in the polls for a number of reasons and had lost the confidence of the Labor Party Caucus, which, fearing defeat in the upcoming election, installed Julia Gillard in his place. Gillard argued it was wrong to give special privileges to asylum seekers. She was against a return to the Pacific Solution, instead arguing for the establishment of a regional offshore processing centre. Gillard's new position was welcomed in the polls, and in the August 2010 election, Labor retained power in a minority government supported by a number of independents.[24]

In May 2011, the Gillard government announced plans to address the issue by swapping new asylum seekers for long-standing assessed refugees in Malaysia. The so-called Malaysian Solution was eventually ruled unconstitutional, partly because Malaysia was not a signatory to the UN Refugee Convention.[34] In 2011, Australia received 2.5% of the world's total number of claims for asylum.[35] During 2012, more than 17,000 asylum seekers arrived via boat.[36] The majority of the refugees came from Afghanistan, Iran, and Sri Lanka.[1]

In June 2012, an accident led to 17 confirmed deaths, with 70 other people missing.[37]

Offshore processing resumed, PNG solution: 2012–2013

In June 2012, Gillard appointed an expert panel to make recommendations on the asylum issue by August 2012.[38] The report included 22 recommendations.[35] Following their recommendations, her government effectively reinstated the Pacific Solution, and re-introduced offshore processing for asylum seekers. Some Labor members complained that Gillard had abandoned her principle for the sake of politics. Greens' Senator Sarah Hanson Young called offshore processing "a completely unworkable, inhumane, unthinkable proposition".[29] The Nauru processing facility was reopened in September, and the Manus Island facility in Papua New Guinea reopened in November.[39][40] However, the centres could not keep up with demand, creating a large backlog.[1] The first 6 months of the policy did not see a reduction in immigration attempts — in the first half of 2013, there were more than 15,000 asylum seekers.[36] For the 6 months to June 2014 however, the number has appeared to sharply reduce, with the immigration minister Scott Morrison claiming that there "had (not been) a successful people smuggling venture" in the period.[41]

In July 2013, Rudd, who had recently returned to power as Prime Minister, announced that anyone who arrived in Australia by boat without a visa would not be eligible for asylum.[1] In co-operation with Papua New Guinean Prime Minister Peter O’Neill, the Regional Settlement Agreement was drafted. Under the agreement, new asylum seekers would be sent to Papua New Guinea where legitimate cases would be granted asylum in that, but would lose any right to seek asylum in Australia.[42] To accommodate the refugees, the Manus Island processing facility would be enlarged significantly. In exchange for taking the asylum seekers, Papua New Guinea will receive financial aid from Australia. Like Australia, Papua New Guinea is a signatory to United Nations Refugees Convention.[36] Rudd said the policy was not intended to be permanent and would be reviewed annually.[1]

Announcing the new policy, Rudd remarked "Australians have had enough of seeing people drowning in the waters to our north. Our country has had enough of people smugglers exploiting asylum seekers and seeing them drown on the high seas."[1] Liberal Party leader Tony Abbott praised the substance of plan, but said Rudd's government was incapable of making it work. Greens leader Christine Milne, however, called the plan "absolutely immoral".[42] Human rights groups criticized the decision. "Mark this day in history as the day Australia decided to turn its back on the world's most vulnerable people, closed the door and threw away the key," said Graeme McGregor of Amnesty International Australia.[1] Human rights lawyer David Mann called it a "fundamental abrogation of Australia's responsibilities" and doubted the legality of the policy.[1] He has also questioned the record of human rights in Papua New Guinea.[43]

The New York Times described Rudd's decision as likely "part of a concerted effort" to nullify opposition attacks ahead of the 2013 federal election.[1] He had been under fire for the unpopular programs of Gillard that led to his return to power, and immigration had become a major issue in the election campaign.[1][36]

Concurrent with Rudd's announcement, Indonesia announced it would toughen requirement for Iranians seeking visas, a change that had been requested by Australia. An Indonesia spokesperson denied that the change in policy was because of an Australian request.[1]

2014-2015

At the end of 2014, the Australian government created a Fast Track Assessment process for those applying for protection visas. The Fast Track Assessment Process started on 19 April 2015. This process assessed the people who arrived in Australia by boat between the dates (inclusive) 13 August 2012 and 1 January 2014.[44]

In 2015, the government of Tony Abbott rejected suggestions that it would accept Rohingyas (a persecuted Muslim minority in Myanmar) during the Rohingya refugee crisis, with the Prime Minister responding "Nope, nope, nope. We have a very clear refugee and humanitarian program".[45] However, later in the year the government unexpectedly increased its intake of refugees to accommodate persecuted minorities (such as Maronites, Yazidis and Druze) from the conflicts of the Syrian Civil War and Iraq War.[46][47]

Closure of Manus Island: 2016

The Australian government ruled out bringing people held on Manus Island to Australia. New Zealand's offer to resettle 150 refugees within its existing quota was refused by the Australian Government.[48] United States officials began assessing applications for asylum for refugees to be resettled in the United States as part of a deal struck with the Australian government.[49]

More than 600 asylum seekers have died en route to Australian territory since 2009.[1]

Contemporary Policy Trends

A number of changes have been implemented in relation to mandatory detention, both broadening opportunities for community integration by offering community alternatives and narrowing release through the creation of new immigration status designations.

Community placements

Those granted Bridging Visas are able to access basic government services, including Centrelink and Medicare. They are able to move freely within their community, but are unable to choose the community that they live in, required to live an address designated by the Minister for Immigration and Border Protection.[48]

Work rights

For the designated refugees that are eligible for work, many are prevented from entering the work force owing to issues of cultural competency and language. The overall effect is that the great majority of refugees in Australia are eager to workout without any pathways into the Australian work force.[48]

Refugees with adverse security assessment

Recent administrative changes have seen the introduction of a new category of designated immigration status: adverse security assessments.[48]

Visa cancellations and the Border Force Act

The Australian Border Force Act 2015 (Cth) makes it a crime punishment of two years imprisonment for an entrusted person to make record of or disclose ‘protected information’. This raises issues relating to judicial power. By denying the court's access to information by which to evaluate a matter, it constitutes an impermissible interference on the functions of a court following the decision in Graham v Minister for Immigration and Border Control. The matter has yet be fully resolved.[48]

Offshore Processing

Australia's humanitarian program is complex, but the basic structure is one of bifurcation between onshore and offshore processing of claims for people seeking asylum. While the onshore humanitarian program is common across most signatories to the 1951 Refugee Convention, it is Australia's offshore detention policy that is the most controversial and widely criticized by civil society members.[50]

Australia is the only nation-state that currently employs a policy of shifting potential people seeking asylum by boat to other nation-states for processing of asylum claims. This policy receives support from both major political parties.[50]

Arrival and Processing in Australia

Historically, Australia is generally viewed as world leader in resettling refugees, with more than 870,000 refugees resettled in Australia since World War II. Yet Australia is also one of the world’s poorest in providing durable solutions to people who come here to claim protection – people seeking asylum – especially if they come by boat.[50] This dichotomy has persisted into the present.

The processing of people seeking asylum that have arrived in Australia for status determination has undergone significant change over the past decade.[51] The process for refugee status determination is dynamic, with the government's humanitarian program mainly diverging in process between on-shore and off-shore arrivals.[51] While the Migration Act 1958 (Cth) had previously drafted to give effect to Australia's obligations under international law,[52] mainly the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees and its First Optional Protocol, recent legislative amendments by successive governments have uncouple the Act from giving effect to the Convention. This has resulted in a softening on the impact of the Convention in interpreting the Act, leading to the government resiling from the protocol set out in the international agreement.[53]

After arriving in Australia, the experience for any individual persons seeking asylum is largely impacted by the location they are placed, socioeconomic status, country of origin, age, sex and knowledge of the area, including family or friends that were in Australia prior to their arrival. Nonetheless, there are recurrent difficulties that surface continuously in asylum seeker communities across Australia, in the interim between arrival and refugee status determination.[54]

Housing Challenges

For asylum seekers that arrive in Australia and receive a temporary protection visa (subclass 785),[55] they are given the right to live in the community and are largely given autonomy to choose housing. The Australian government does not provide services to link asylum seekers with potential housing.[54] Their ephemeral status in the country, entirely dependent on status determination by the government, leads to apprehension amongst housing providers arising from concern that they may not remain in Australia for the duration of the lease. The lack of clarity and certainty owing to their undefined legal status therefore deters housing providers from offering leases to asylum seekers.[54]

Compounding this factor is the exceptionally low income for most asylum seekers, arising from their inability to work legally in Australia (an issue that will be comprehensively discussed below).[54] These low wages limit housing options for asylum seekers and leaves them susceptible to a higher risk of exploitation. Substandard housing conditions clearly follows from this difficulty.[54] One instance in Adelaide found 20 temporary protection visa holders living in a single address, while a service provider in Sydney reported instances where people seeking asylum had been convinced by real estate agents to rent non-residential properties such as warehouses with dividers between the beds.[54]

General issues prevalent across most major cities in Australia in relation to housing are compounded in severity for asylum seekers.[54] Housing affordability for most areas in proximity to city centres has become out of reach for both buyers and renters.[56] In the two largest cities of Sydney and Melbourne, housing availability is an additional strain for renters, with a competitive market leading to some perpetually searching for housing.[56] The impact these general issues have on asylum seekers searching for housing open arrival into Australia is therefore significant and, at times, debilitating, leading to substantial possibility of homelessness throughout these communities.[54]

Income and Work Rights

Asylum seekers in Australia are precluded from the ability to work until a determination is made on their refugee status.[57] The timeline for status determination varies considerably on a case by case basis. Until the passage of the Migration and Maritime Powers (Resolving the Asylum Legacy Caseload) Act 2015 (Cth), the Commonwealth was required to report the percentage of decisions made within 90 days of lodging their application. From 2013–14, the Department of Immigration and Border Protection made just seven percent of initial decisions within the given timeframe.[58] While more current data is unavailable, it is unlikely that the change of Liberal leadership (and therefore government) from Abbott to Turnbull has raised these rates. This means that it is likely that the overwhelming majority of asylum seekers in Australia are unable to work for well over three months while they wait for status determination.[58]

The lack of ability to work forces asylum seekers in Australia to rely heavily on Centrelink payments.[54] Their capacity to earn is then greatly reduced and there is an identifiable gap in the interstice between application for refugee status and refugee status determination where asylum seekers in Australia are placed into a tenuous financial position.[54]

The bleak outlook on income are working rights so described leads to a direct impact on the mental health of the asylum seeker community.[54] For those asylum seekers that go on to be recognised as legally defined refugees, the labour opportunities are largely seen as a window dressing exercise.[54] The support given is unspecialised, with jobactive largely ignoring the unique difficulties newly recognised refugees possess when searching for and obtaining work.[54]

Procedural Challenges

The Status Resolution Support Services (SSRS) is the Department of Immigration and Border Protection's replacement for the previous Community Assistance Program (CAP) that is meant to connect migrants and non-citizens with social services.[59] The services are delivered under six different bands that vary dependent upon identity and timeline of asylum.[54] There are issues latent within the SSRS arising from a strict adherence to the band taxonomy that leads to a stringent, and at times problematic, application of the band criteria.[54] There is the additional strain of a high caseworker to client ratio of 1:120, which has largely been viewed as a compromise on quality.

The Code of Behaviour is an agreement asylum seekers sign when arriving in Australia that largely binds them to certain standards of behaviour while awaiting refugee status determination.[60] This has been received by the community as casting a dark shadow for asylum seekers' experience in Australia, with many of the signees feeling that the agreement creates uncertainty and confusion as to which actions may jeopardise their applications.[54] The effect of the Code of Behaviour has deterred refugees from community events out of fear that their participation could contribute to a denial of their applications.[54]

Public debate and politics

Opinion polls show that boat arrivals have always been an issue of concern to the Australian public, but opposition has increased steadily over the previous four decades, according to a 2013 research paper by the Parliamentary Library.[5]

In 2005, the wrongful incarceration of Cornelia Rau was made public through the Palmer Inquiry, which stimulated concern in the Australian public about the detention of children in remote locations and the potential for resultant long-term psychological harm.[10]

Between 1998 and 2008, the UN Human Rights Committee made adverse findings against Australia in a number of immigration detention cases, concluding that Australia had violated the prohibition on arbitrary detention in Article 9(1) of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.[10] The longest-held detainee within the Australian immigration detention system was Peter Qasim, who was detained for six years and ten months.[61]

In March 2012, former Prime Minister Paul Keating said there were "racial undertones" to the debate and that Australia's reputation in Asia was being damaged.[62] In 2013, former Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser described the positions of the major political parties as a "race to the bottom".[63]

In 2003, economist Ross Gittins, a columnist at Fairfax Media, said former Prime Minister John Howard had been "a tricky chap " on immigration, by appearing "tough" on illegal immigration to win support from the working class, while simultaneously winning support from employers with high legal immigration.[64]

In 2016, the UN Special Rapporteur on the human rights of migrants, François Crépeau, criticised Australia's policies of mandatory and off-shore immigration detention. Crépeau claimed that Australia had adopted a "punitive approach" towards migrants who arrived by boat which had served to "erode their human rights".[65]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Matt Siegel (19 July 2013). "Australia Adopts Tough Measures to Curb Asylum Seekers". The New York Times. Retrieved 20 July 2013.

- 1 2 John Menadue (8 March 2012). "The Pacific Solution didn't work before and it won't work now". Centre for Policy Development. Retrieved 21 July 2013.

- 1 2 "Government announces increase in refugee intake". ABC News. 23 August 2012. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- ↑ Gibney, Matthew J. (2004). The Ethics and Politics of Asylum: Liberal Democracy and the Response to Refugees. Cambridge University Press. p. 166. ISBN 0521009375. Retrieved 21 July 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Janet Phillips & Harriet Spinks (5 January 2011). "Boat arrivals in Australia since 1976". Background Notes. Commonwealth of Australia. Retrieved 21 July 2013.

- ↑ "Asylum seekers and refugees What are the facts". Retrieved 3 October 2014.

- ↑ http://www.news.com.au/world/ten-myths-around-asylum-seekers-arriving-on-boats-in-australian-waters/story-fndir2ev-1226676024840

- ↑ Rogers, Simon (2 July 2013). "Australia and asylum seekers: the key facts you need to know". The Guardian. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- ↑ "Australia under fire at UN over asylum seeker policies". ABC News. 2015-11-10. Retrieved 2016-12-08.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Sawer, Marian; Norman Abjorensen; Philip Larkin (2009). Australia: The State of Democracy. Federation Press. pp. 27, 65–67. ISBN 1862877254. Retrieved 21 July 2013.

- ↑ Mares, Peter (2002). Borderline: Australia's Treatment of Refugees and Asylum Seekers in the Wake of the Tampa. UNSW Press. pp. 3, 8. ISBN 0868407895. Retrieved 20 July 2013.

- ↑ Mann, Tom (2003). Desert Sorrow: Asylum Seekers at Woomera. Wakefield Press. p. 1. ISBN 1862546231. Retrieved 20 July 2013.

- 1 2 3 http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/legis/cth/consol_act/ma1958118/s36.html

- ↑ "Proposing an Immediate Family Member ('Split Family')". Department of Immigration and Citizenship. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- ↑ https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/F2016L00679

- ↑ "At-a-glance: Who takes the most asylum claims?". SBS. 5 January 2011. Retrieved 20 July 2013.

- ↑ "Australia's Refugee Response Not The Most Generous But in Top 25" (PDF). Refugee Council of Australia. 19 July 2013. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- ↑ Refugee Council of Australia. "Australia's Refugee Response Not the Most Generous but in Top 25" (PDF). Retrieved 3 October 2014.

- ↑ Australia’s Humanitarian Program: a quick guide to the statistics since 1947, Parliamentary Library of Australia, 17 January 2017, retrieved 27 November 2017

- ↑ Boat arrivals and boat ‘turnbacks’ in Australia since 1976: a quick guide to the statistics, Parliamentary Library of Australia, 17 January 2017, retrieved 27 November 2017

- ↑ Immigration to Australia During the 20th Century Archived 18 September 2012 at the Wayback Machine.. Department of Immigration and Citizenship. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- ↑ Brennan, Frank (2007). Tampering with Asylum: A Universal Humanitarian Problem. University of Queensland Press. p. 1. ISBN 0702235814. Retrieved 20 July 2013.

- 1 2 3 McMaster, Don (2001). Asylum Seekers: Australia's Response to Refugees. Melbourne University Publish. pp. ix, 3. ISBN 052284961X. Retrieved 20 July 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Robert Manne (September 2010). "Comment: Asylum Seekers". The Monthly. Retrieved 20 September 2015.

- 1 2 Kessels, Ronald; Maritsa Eftimiou (1993). "Effects of incarceration". In Crock, Mary. Protection Or Punishment: The Detention of Asylum Seekers in Australia. Federation Press. pp. 93–94. ISBN 1862871256. Retrieved 20 July 2013.

- ↑ "Tampa Crisis". Infobase. Heinemann Interactive. Archived from the original on 21 August 2006. Retrieved 20 July 2013.

- ↑ "Election Speeches John Howard, 2001". Museum of Australian Democracy at Old Parliament House. 28 October 2001. Retrieved 20 July 2013.

- ↑ "Human Rights Law Bulletin Volume 2". Australian Human Rights Commission.

- 1 2 Phil Mercer (15 August 2012). "Is Australia asylum U-turn a 'better option'?". BBC. Retrieved 20 July 2013.

- 1 2 Crock, Mary (2006). Seeking Asylum Alone, Australia: A Study of Australian Law, Policy and Practice Regarding Unaccompanied and Separated Children. Federation Press. pp. 11–12. ISBN 1921113014. Retrieved 20 July 2013.

- ↑ "Asylum seekers, the facts in figures". Crikey.com.au. 17 April 2009.

- ↑ Authorities: Death toll up to 48 in Christmas Island shipwreck

- ↑ "Australian Immigration Fact Sheet 60 – Australia's Refugee and Humanitarian Program". Commonwealth of Australia. Archived from the original on 8 July 2013. Retrieved 20 July 2013.

- ↑ "Malaysia Swap Deal For Asylum Seekers Ruled Unlawful By High Court". The Sydney Morning Herald. 31 August 2011.

- 1 2 Neil Hume (14 August 2012). "Australia debates offshore asylum centres". Financial Times. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 "Australia to send asylum-seekers to PNG". BBC. 19 July 2013. Retrieved 20 July 2013.

- ↑ "Boat sinking reignites Australia asylum debate". BBC. 25 June 2012.

- ↑ "Expert Panel on Asylum Seekers: About". Commonwealth of Australia. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- ↑ "Australia flies first asylum seekers to Nauru camp". BBC. 14 September 2012. Retrieved 20 July 2013.

- ↑ "First asylum seekers arrive on Manus Island". ABC. 21 November 2012.

- ↑ "Morrison says no asylum seeker boat arrivals despite reports". ABC. 30 June 2014.

- 1 2 Paul Bleakley (19 July 2013). "Rudd says no illegal boat arrivals will resettle in Australia". Australian Times. Retrieved 19 July 2013.

- ↑ Oliver Laughland (19 July 2013). "Christine Milne laments 'Australia's day of shame' on asylum". The Guardian. Retrieved 20 July 2013.

- ↑ Anon, 2015. The Fast Track Assessment Process. [pdf] Refugee Council of Australia, p.1. Available at: <http://www.refugeecouncil.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/Fast-track-Fact-sheet.pdf> [Accessed 31 Jul. 2016].

- ↑ Belinda Grant Geary (21 May 2015). "'Nope, Nope, Nope': Tony Abbott's blunt response when asked if Australia would accept hundreds of desperate refugees pictured stranded on rotting boats off Indonesia". Daily Mail Australia. Retrieved 13 September 2015.

- ↑ "Migrants and Australia: Why Australia is accepting 12,000 more Syrian migrants". The Economist. 9 September 2015. Retrieved 12 September 2015.

- ↑ Lenore Taylor; Shalailah Medhora (8 September 2015). "Tony Abbott to confirm Syrian airstrikes as pressure grows over refugees". The Guardian. Retrieved 12 September 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 RCOA (July 2016). "Recent Changes in Australian Refugee Policy" (PDF). Refugee Council of Australia.

- ↑ "US hits refugee intake cap as Manus Island, Nauru refugees assessed".

- 1 2 3 Refugee Council of Australia, 'State of the Nation: Refugees and People Seeking Asylum in Australia' (2017) Refugee Council of Australia Reports 1.

- 1 2 "Fact sheet - Australia's Refugee and Humanitarian programme". www.border.gov.au. Retrieved 2017-08-18.

- ↑ Migration Act 1958 (Cth) ss 198, 198A

- ↑ Migration Act 1958 (Cth), s 198AA

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Refugee Council of Australia (December 2015). "Eroding Our Identity as a Generous Nation: Community Views on Australia's Treatment of People Seeking Asylum" (PDF). RCOA.

- ↑ "Temporary Protection visa (subclass 785)". www.border.gov.au. Retrieved 2017-08-18.

- 1 2 Nicholls, Seth (2014). "Perpetuating the problem: Neoliberalism, Commonwealth public policy and housing affordability in Australia". Australian Journal of Social Issues. 49 (3): 329–347.

- ↑ Matthew.Bretag (2013-04-17). "Tell Me About: Bridging Visas for Asylum Seekers". www.humanrights.gov.au. Retrieved 2017-08-18.

- 1 2 "Refugee Status Determination in Australia | Factsheet | Kaldor Centre". www.kaldorcentre.unsw.edu.au. Retrieved 2017-08-18.

- ↑ "SRSS Programme". www.border.gov.au. Retrieved 2017-08-18.

- ↑ Department of Immigration and Border Protection (October 2015). "Code of Behaviour for Subclass 050" (PDF).

- ↑ Andra Jackson (5 January 2008). "Our lives are in limbo: former detainees". The Age. Fairfax Digital. Retrieved 2 August 2013.

- ↑ Paul Maley (23 March 2012). "Paul Keating slams 'racist' tone of asylum debate". The Australian. Retrieved 20 July 2013.

- ↑ "Malcolm Fraser backs Greens senator". The Sydney Morning Herald. 6 July 2013. Retrieved 20 July 2013.

- ↑ Gittens, R. (20 August 2003). Honest John's migrant twostep. The Age. Retrieved 2 October from http://www.theage.com.au/articles/2003/08/19/1061261148920.html

- ↑ ""Australia's human rights record blemished by punitive approach to migrants" – UN rights expert". www.ohchr.org. Retrieved 2017-01-02.