Ragged school

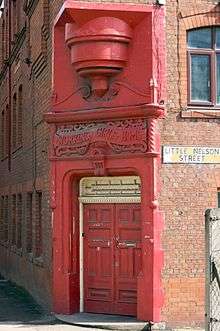

Ragged school and Working Girls Home doorway, Dantzic Street, Manchester | |

| Formation | 1844 |

|---|---|

| Type | Nonprofit |

| Purpose | Social and educational reform |

| Headquarters | London, England |

| Location |

|

Region served | England, Scotland, and Wales |

| Remarks | Ragged Schools became the Shaftesbury Society, which merged with John Grooms in 2007 and adopted the name Livability. |

Ragged schools were charitable organisations dedicated to the free education of destitute children in nineteenth-century Britain. The schools were developed in working-class districts. Ragged schools were intended for society's most destitute children. Such children, it was argued, were often excluded from Sunday School education because of their unkempt appearance and often challenging behaviour. The London Ragged Schools Union was established in April 1844 to combine resources in the city, providing free education, food, clothing, lodging and other home missionary services for poor children.[1] Although the London Ragged School Union did not extend beyond the metropolis, its publications and pamphlets helped spread ragged school ideals across the country.

Working in the poorest districts, teachers (who were often local working people) initially utilised stables, lofts, and railway arches for their classes. The majority of teachers were voluntary, although a small number were employed. There was an emphasis on reading, writing, arithmetic, and study of the Bible. The curriculum expanded into industrial and commercial subjects in many schools. It is estimated that about 300,000 children went through the London ragged schools alone between 1844 and 1881.[1]

The Ragged School Museum in the East End of London shows how a ragged school would have looked; it is housed in buildings previously occupied by Dr Thomas Barnardo. The Ragged School Museum provides an idea of the working of a ragged school, but Thomas Barnardo's institution differed considerably in practice and philosophy from those schools accountable to the London Ragged School Union.

Early days

Several different schools claim to have pioneered truly free education for impoverished children. For many of the destitute children of London, going to school each day was not an option. From the 18th century onwards, schools for poor children were few and far between. They had been started in areas where someone had been concerned enough to want to help disadvantaged children towards a better life.[2]

In the late eighteenth century Thomas Cranfield offered free education for poor children in London. While he was a tailor by trade, Cranfield's educational background included studies at a Sunday school on Kingsland Road, Hackney. In 1798, he established a free children's day school on Kent Street near London Bridge. By the time of his death in 1838, he had established 19 free schools providing services for children and infants living in the lower-income areas of London. These opportunities and services were offered days, nights, and on Sundays, for the destitute children of poor families throughout London.[3][4]

John Pounds, a Portsmouth shoemaker, provided important inspiration for the movement. At the age of twelve Pounds' father arranged for him to be apprenticed as a shipwright. Three years later, he fell into a dry dock and was crippled for life after damaging his thigh. Unable to work as a shipwright, John became a shoemaker and, by 1803, had his own shop in St Mary Street, Portsmouth. In 1818, Pounds, known as the crippled cobbler, began teaching poor children without charging fees. He actively recruited children and young people to his school. He spent time on the streets and quays of Portsmouth making contact and even bribing them to come with the offer of baked potatoes.[5] He began teaching local children reading, writing, and arithmetic. His reputation as a teacher grew and he soon had more than 40 students attending his lessons. He also gave lessons in cooking, carpentry and shoemaking. Pounds died in 1839.[4] Pounds quickly became a figurehead for the schools; his ethos was used as an inspiration for the later movement.

In 1841 Sheriff Watson established a school in Aberdeen, Scotland. Unlike the earlier efforts of Pounds and Cranfield, Watson used compulsion to increase attendance at the institution. Watson was frustrated by the number of children who committed a petty crime and faced him in his courtroom. Rather than sending them to prison for vagrancy, Watson established a school for boys. As a law official, the sheriff arrested the vagrant children and enrolled them in school.[4]

The Industrial Feeding School opened to provide reading, writing and arithmetic. Watson believed that gaining these skills would help the boys rise above the lowest level of society. It was not confined to the 'three R's', however, as the young scholars also received instruction on geology.[6] Three meals a day were provided and the boys were taught useful trades such as shoemaking and printing. A school for girls followed in 1843. In 1845, the schools were integrated. From here, the movement spread to Dundee and other parts of Scotland.

The same year that Watson established his school in Aberdeen, the Field Lane ragged school began in Clerkenwell, London. Historians have debated how connected the movement was between England and Scotland. E.A.G. Clark argued that ‘the London and Scottish schools had little in common except their name’.[7] More recently, Laura Mair has demonstrated that literature, philosophy and passionate individuals were shared between schools. She writes that 'schools forged significant links across cities and countries that disregarded physical distance'.[8] It was S. R. Starey, the secretary of the Field Lane ragged school, who first applied the term 'ragged' to the institutions in an advert he submitted to The Times seeking public support. [9]

Although the Edinburgh Original Ragged School, established by the Reverend Thomas Guthrie in April 1847, was not the first ragged school in Scotland, Guthrie was later acknowledged as a core leader of the movement. His 'Plea for Ragged Schools', published in March 1847 to garner the public's support for a school in the city, laid out his indisputable arguments that proved highly influential. Guthrie was first introduced to the idea of a ragged schools in 1841, while acting as the Parish Minister of St. John’s Church in Edinburgh. On a visit to Anstruther in Fife, he saw a picture of John Pounds in Portsmouth and felt inspired and humbled by the cobbler's work.

Birth of the organisation

In April 1844, Locke, Moutlon, Morrison, and Starey formed a steering committee to address the social welfare needs of the community. On 11 April 1844, at 17 Ampton Street off the Grays Inn Road, they facilitated a public meeting to determine local interest, research feasibility, and establish structure. This was the birth of the Ragged Schools Union.[1][4] In 1944, the Union adopted the name "Shaftesbury Society" in honour of the 7th Earl of Shaftesbury. In 2007, the Society was merged with John Grooms, taking the new name of Livability.

Mr Locke of the Ragged School Union called for more help in keeping the schools open. Many petitions for funding and grants were made to Parliament to assist with educational reform. He asked the government to give more thought to preventing crime, rather than punishing the wrongdoers. He said the latter course only made the young criminals worse.[1][2]

In 1840, the Mission used the term "ragged" in its Annual Report to describe their establishment of five schools for 570 children. In the report, the Mission reported that their schools had been formed exclusively for children "raggedly clothed". The children only had very ragged clothes to wear and they rarely had shoes. In other words, they did not own clothing suitable to attend any other kind of school.[1][10]

Prominent supporters

Several people volunteered and offered their time, skills, and talents as educators and administrators of the ragged schools. Anthony Ashley-Cooper, 7th Earl of Shaftesbury was one of Britain's greatest social reformers, whose broad-ranging concerns included education, animal welfare, public health and improving working conditions.

In 1844 Lord Shaftesbury became the president of the ragged schools. He used his knowledge of the schools, the refuges, and his understanding of the living conditions among low-income families to pursue changes in legislation. He served as the president of the London Ragged School Union for 39 years. In 1944 the Union adopted the name "Shaftesbury Society" in his honour. Shaftesbury maintained his commitment to the Ragged Schools and educational reform until his death in 1885.

In 1843, Charles Dickens began his association with the schools and visited the Field Lane Ragged School.[11] He was appalled by the conditions, yet moved toward reform.[12] The experience inspired him to write A Christmas Carol. While he initially intended to write a pamphlet on the plight of poor children, he realised that a dramatic story would have more impact.

Dickens continued to support the schools, donating funds on various occasions. At one point, he donated funds, along with a water trough, stating that it was "so the boys may wash and for a supervisor"! (from a letter to Field Lane). He later wrote about the school and his experience there in Household Words. In 1837, he used the area called Field Lane as a setting for Fagin’s den in his classic novel, Oliver Twist.

Growth of the organisation

By 1844, there were at least 20 free schools for the poor, maintained through the generosity of community philanthropists, the volunteers working with their local churches, and the organisational support of the London City Mission. During this time, it was suggested that it would be beneficial to establish an official organisation or society to share resources and promote their common cause.

In April 1844 the London Ragged School Union was founded during a meeting of four men to pray for the city's poor children. Starey, the secretary of Field Lane school, was present. There was a massive growth in the numbers of schools, teachers and students. By 1851, the number of educators would grow to include around 1,600 persons. By 1867, some 226 Sunday Ragged Schools, 204 day schools and 207 evening schools provided a free education for about 26,000 students.[1] However, the schools were heavily reliant on volunteers and continually faced problems in finding and keeping staff. Women played an important role as volunteer teachers. A newspaper report on the progress of the schools announced that 'the most valuable teachers in ragged schools are those of the female sex’.[13]

The ragged school movement became respectable, even fashionable, attracting the attention of many wealthy philanthropists. Wealthy individuals such as Angela Burdett-Coutts gave large sums of money to the London Ragged School Union. This helped to establish 350 ragged schools by the time the 1870 Education Act was passed.[14] As Eager (1953) explains, "He gave what had been a Nonconformist undertaking, the cachet of his Tory churchmanship – an important factor at a time when even broad-minded (Anglican) churchmen thought that Nonconformists should be fairly credited with good intentions, but that cooperation (with them) was undesirable".[1][15]

Legacy of the ragged schools

The success of the ragged schools definitively demonstrated that there was a demand for education among the poor. In response, England and Wales established school boards to administer elementary schools. However, education was still not free of fees. After 1870 public funding began to be provided for elementary education among working people.

School boards were public bodies created in boroughs and parishes under the Elementary Education Act 1870 following campaigning by George Dixon, Joseph Chamberlain and the National Education League for elementary education that was free from Anglican doctrine. Members to the board were directly elected, not appointed by borough councils or parishes. As the school boards were built and funded, the demand for ragged schools declined. The Board Schools continued in operation for 32 years. They were officially abolished by the Education Act 1902, which replaced them with local education authorities.

Ragged School Museum

Founded in 1990, a Ragged School Museum occupies a group of three canalside buildings on Copperfield Road in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets that once housed the largest ragged school in London; the buildings had previously been used by Dr Thomas Barnardo.

Barnardo arrived in London in 1866, planning to train as a doctor and become a missionary in China. In London, he was confronted by a city where disease was rife, poverty and overcrowding endemic and educational opportunities for the poor were non-existent. He watched helplessly as a cholera epidemic swept through the East End, leaving more than 3,000 Londoners dead and many destitute. He gave up his medical training to pursue his local missionary works and in 1867, opened his first ragged school, where children could gain a free basic education. Ten years later, Barnardo’s Copperfield Road School opened its doors to children and for the next thirty-one years educated tens of thousands of children. It closed in 1908, by which time enough government schools had opened in the area to serve the needs of local families.

The buildings, originally warehouses for goods transported along the Regent’s Canal, then went through a variety of industrial uses until, in the early 1980s, they were threatened with demolition. A group of local people joined together to save them and reclaim their unique heritage. The Ragged School Museum Trust was set up and the museum opened in 1990.

The museum was founded to make the history of the ragged schools and the broader social history of the East End accessible to all. An authentic Victorian classroom has been set up within the original buildings, in which 14,000 children each year experience a school lesson as it would have been taught more than 100 years ago.

See also

- Rosenwald Schools, in the United States

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Walvin, J. (1982). A Child’s World. A social history of English childhood 1800–1914. Pelican. ISBN 0-14-022389-4.

- 1 2 "Ragged Schools, Industrial Schools and Reformatories". Hidden Lives Revealed. Retrieved 9 July 2010.

- ↑ Eager, W. McG. Making Men: the history of the Boys’ Clubs and related movements in Great Britain, London:University of London Press, 1953, p. 121

- 1 2 3 4 Smith, M. K. (2001). "Ragged Schools and Youth Work". Retrieved 9 July 2010.

- ↑ Caroline Cornwallis, 'The Philosophy of the Ragged Schools' (London: Pickering, 1851), p. 43.

- ↑ W. Watson, 'Chapters on Ragged and Industrial Schools' (Edinburgh: Blackwood and Sons, 1872), p. 16.

- ↑ E.A.G. Clark, ‘The Ragged School Union and the Education of the London Poor in the Nineteenth Century’ (unpublished Master’s thesis, University of London, 1967), pp. 8-9.

- ↑ Laura M. Mair '"The Only Friend I have in this World": Ragged School Relationships in England and Scotland, 1844-1870' (unpublished PhD thesis, University of Edinburgh, 2017), p. 60.,

- ↑ Mair, pp. 52-53

- ↑ Montague, C.J. Sixty Years in Waifdom. Or, the Ragged School Movement in English history, London:Charles Murray, 1904, p. 34

- ↑ History of Field Lane Ragged School Archived 19 July 2013 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Charles Dickens and the Ragged Schools

- ↑ Mair, p. 83.

- ↑ History of the Ragged Schools

- ↑ Eager, W. McG. Making Men: the history of the Boys’ Clubs and related movements in Great Britain, London:University of London Press, 1953, p. 123

![]()

External links

- "The First Ragged School, Westminster" (oil painting) Birmingham Museums & Art Gallery

- In 2007 the Shaftesbury Society merged with John Grooms to form Livability History of Livability