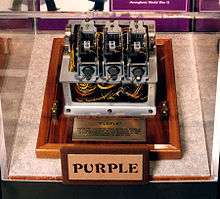

Type B Cipher Machine

In the history of cryptography, "System 97 Typewriter for European Characters" or "Type B Cipher Machine", codenamed Purple by the United States, was a diplomatic cryptographic machine used by the Japanese Foreign Office just before and during World War II. The machine was an electromechanical stepping-switch device using a 6 X 25 substitution table.[1]

The codename "Purple" referred to binders used by US cryptanalysts for material produced by various systems; it replaced the Red machine used by the Japanese Foreign Office. The Japanese also used Coral and JADE stepping-switch systems. American forces referred to information gained from decryptions as Magic.

Development of Japanese cipher machines

Overview

The Imperial Japanese Navy did not cooperate with the Army in pre-war cipher machine development, and that lack of cooperation continued into World War II. The Navy believed the Purple machine was sufficiently difficult to break that it did not attempt to revise it to improve security. This seems to have been on the advice of a mathematician, Teiji Takagi, who lacked a background in cryptanalysis. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs was supplied Red and Purple by the Navy. No one in Japanese authority noticed weak points in both machines.

Just before the end of the war, the Army warned the Navy of a weak point of Purple, but the Navy failed to act on this advice.

The Army developed their own cipher machines on the same principle as Enigma, '92-shiki injiki', 97-shiki injikiand 1-shiki 1-go injiki一from 1932 to 1941. The Army judged that these machines had lower security than the Navy's Purple design, so the Army's two cipher machines were less used.

Prototype of Red

Japanese diplomatic communications at negotiations for the Washington Naval Treaty were broken by the American Black Chamber in 1922, and when this became publicly known, there was considerable pressure to improve their security. In any case, the Japanese Navy had planned to develop their first cipher machine for the following London Naval Treaty. Japanese Navy Captain Risaburo Ito, of Section 10 (cipher & code) of the Japanese Navy General Staff Office, supervised the work.

The development of the machine was the responsibility of the Japanese Navy Institute of Technology, Electric Research Department, Section 6. In 1928, the chief designer Kazuo Tanabe and Navy Commander Genichiro Kakimoto developed a prototype of Red, "Roman-typewriter cipher machine".

The prototype used the same principle as the Kryha cipher machine, having a plug-board, and was used by the Japanese Navy and Ministry of Foreign Affairs at negotiations for the London Naval Treaty in 1930.

Red

The prototype machine was finally completed as "Type 91 Typewriter" in 1931. The year 1931 was year 2591 in the Japanese Imperial calendar. Thus it was prefixed "91-shiki" from the year it was developed.

The 91-shiki injiki Roman-letter model was also used by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs as "Type A Cipher Machine", codenamed "Red" by United States cryptanalysts.

The Red machine was unreliable unless the contacts in its half-rotor switch were cleaned every day. It enciphered vowels (AEIOUY) and consonants separately, perhaps to reduce telegram costs, and this was a significant weak point. The Navy also used the 91-shiki injiki Kana-letter model at its bases and on its vessels.

Purple

In 1937, the Japanese completed the next generation "Type 97 Typewriter". The Ministry of Foreign Affairs machine was the "Type B Cipher Machine", codenamed Purple by United States cryptanalysts.

The chief designer of Purple was Kazuo Tanabe. His engineers were Masaji Yamamoto and Eikichi Suzuki. Eikichi Suzuki suggested the use of a stepping switch instead of the more troublesome half-rotor switch.

Clearly, the Purple machine was more secure than Blue, but the Navy did not recognize that Red had already been broken. The Purple machine inherited a weakness from the Red machine that six letters of the alphabet were encrypted separately. It differed from RED in that the group of letters was changed and announced every nine days, whereas in RED they were permanently fixed as the Latin vowels 'a', 'e', 'i', 'o', 'u' and 'y'. Thus US Army SIS was able to break the cipher used for the six letters before it was able to break the one used for the 20 others.

Weaknesses and cryptanalysis

In operation, the enciphering machine accepted typewritten input (in the Latin alphabet) and produced ciphertext output, and vice versa when deciphering messages. The result was a potentially excellent cryptosystem. In fact, operational errors, chiefly in key choice, made the system less secure than it could have been; in that way, the Purple code shared the fate of the German Enigma machine. The cipher was broken by a team from the US Army Signals Intelligence Service, then directed by William Friedman in 1940.[2][3] Reconstruction of the Purple machine was based on ideas of Larry Clark. Advances into the understanding of Purple keying procedures were made by Lt Francis A. Raven, USN. Raven discovered that the Japanese had divided the month into three 10-days periods, and, within each period, they used the keys of the first day, with small predictable changes.

The Japanese believed it to be unbreakable throughout the war, and even for some time after the war, even though they had been informed otherwise by the Germans. In April 1941, Hans Thomsen, a diplomat at the German embassy in Washington, D.C., sent a message to Joachim von Ribbentrop, the German foreign minister, informing him that "an absolutely reliable source" had told Thomsen that the Americans had broken the Japanese diplomatic cipher (that is, Purple). That source apparently was Konstantin Umansky, the Soviet ambassador to the US, who had deduced the leak based upon communications from Sumner Welles. The message was duly forwarded to the Japanese; but use of the code continued.[4][5]

The United States obtained portions of a Purple machine from the Japanese Embassy in Germany following Germany's defeat in 1945 (see image above) and discovered that the Japanese had used precisely the same "stepping switch" in its construction that Leo Rosen of SIS had chosen when building a "duplicate" (or Purple analog machine) in Washington in 1939 and 1940. The "stepping switch" was a uniselector; a standard component used in large quantities in automatic telephone exchanges in countries like America, Britain, Canada, Germany and Japan, with extensive dial-telephone systems. Note however that this was not a two-motion or Strowger switch as sometimes claimed: twenty-five Strolger-type (sic) stepper switches ... :[6]

Apparently, all other Purple machines at Japanese embassies and consulates around the world (e.g. in Axis countries, Washington, London, Moscow, and in neutral countries) and in Japan itself, were destroyed and ground into particles by the Japanese. American occupation troops in Japan in 1945−52 searched for any remaining units.

The Purple machine itself was first used by Japan in June 1938, but U.S. and British cryptanalysts had broken some of its messages well before the attack on Pearl Harbor. U.S. cryptanalysts decrypted and translated Japan's 14-part message to its Washington Embassy breaking off (ominously) negotiations with the United States at 1 p.m. Washington time on 7 December 1941, before the Japanese Embassy in Washington had done so. Decryption and typing difficulties at the Embassy, coupled with ignorance of the importance of it being on time, were major reasons the "Nomura note" was delivered late.

Other factors

During World War II, the Japanese ambassador to Nazi Germany, General Hiroshi Oshima was well-informed on German military affairs. His reports went to Tokyo in Purple-enciphered radio messages. Examples include a comment that Hitler told him on June 3, 1941 that in every probability war with Russia cannot be avoided. In July and August 1942 he toured the Russian front, and in 1944 the Atlantic Wall fortifications against invasion along the coasts of France and Belgium, and on September 4 that Hitler told him that Germany would strike in the West, probably in November.[7] Since these messages were being read by the Allies, this provided valuable intelligence about German military preparations against the forthcoming invasion of Western Europe. He was described by General George Marshall as "our main basis of information regarding Hitler's intentions in Europe".[8]

The decrypted Purple traffic, and Japanese messages generally, was the subject of acrimonious hearings in Congress post-World War II in connection with an attempt to decide who, if anyone, had allowed the attack at Pearl Harbor to happen and who therefore should be blamed. It was during those hearings that the Japanese learned, for the first time, that the Purple cipher machine had indeed been broken. See the Pearl Harbor advance-knowledge conspiracy theory article for additional detail on the controversy and the investigations.

The Russians also succeeded in breaking into the Purple system in late 1941, and together with reports from Richard Sorge, learned that Japan was not going to attack the Soviet Union. Instead, its targets were southward, toward Southeast Asia and US and UK interests there. This allowed Stalin to move considerable forces from the Far East to Moscow in time to help stop the German push to Moscow in December.[9]

References

- ↑ Budiansky 2000, pp. 351-353.

- ↑ Clark, R.W. (1977). The Man who broke Purple. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. pp. 103–112. ISBN 0-297-77279-1.

- ↑ Friedman, William F. (14 October 1940). "Preliminary Historical Report on the Solution of the "B" Machine" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 April 2013. Retrieved 16 February 2013.

- ↑ Langer, Howard (1999). World War II: An Encyclopedia of Quotations. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 198. ISBN 978-0-313-30018-9. Retrieved 2008-02-11.

- ↑ Kahn, David (1996). The Codebreakers: The Comprehensive History of Secret Communication from Ancient Times to the Internet. Scribner.

|access-date=requires|url=(help) Text from excerpt of first chapter on WNYC website Archived 25 January 2008 at the Wayback Machine. - ↑ Costello, John (1994). Days of Infamy: MacArthur, Roosevelt, Churchill – the Shocking Truth Revealed. New York: Pocket Books. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-141-02926-9.

- ↑ Budiansky 2010, pp. 196,268,326.

- ↑ "Marshall-Dewey Letters". Time Inc. Dec 17, 1945. Retrieved 9 June 2018.

- ↑ Kelley, Stephen J. (2001). Big Machines. Aegean Park Press. p. 106. ISBN 0-894122-90-8.

Further reading

- Big Machines, by Stephen J. Kelley (Aegean Park Press, Walnut Creek, 2001, ISBN 0-89412-290-8) – Contains a lengthy, technically detailed description of the history of the creation of the PURPLE machine, along with its breaking by the US SIS, and an analysis of its cryptographic security and flaws

- Budiansky, Stephen (2000). Battle of Wits: The complete story of Codebreaking in World War II. New York: Free Press. pp. 351–353. ISBN 0-684-85932-7. - Appendix C: Cryptanalysis of the Purple Machine

- Clark, Ronald W. "The Man Who Broke Purple: the Life of Colonel William F. Friedman, Who Deciphered the Japanese Code in World War II", September 1977, Little Brown & Co, ISBN 0-316-14595-5.

- Freeman, Wes; Sullivan, Geoff; Weierud, Frode (2003). "Purple Revealed: Simulation and Computer-Aided Cryptanalysis of Angooki Taipu B". Cryptologia. 27 (1): 1–43. doi:10.1080/0161-110391891739.

- Combined Fleet Decoded by J. Prados

- The Story of Magic: Memoirs of an American Cryptologic Pioneer, by Frank B. Rowlett (Aegean Park Press, Laguna Hills, 1998, ISBN 0-89412-273-8) – A first-hand memoir from a lead team member of the team which 'broke' both Red and Purple, it contains detailed descriptions of both 'breaks'

- Smith, Michael (2000). The Emperor’s Codes: Bletchley Park and the breaking of Japan’s secret ciphers. London: Bantam Press. ISBN 0593 046412.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to PURPLE cipher machine. |

- The Purple Machine Information and a simulator (for Windows).

- A Purple Machine simulator written in Python

- A GUI Purple Machine simulator written in Java

- Purple, Coral, and Jade

- Red and Purple: A Story Retold NSA analysts' modern-day attempt to duplicate solving the Red and Purple ciphers. Cryptologic Quarterly Article (NSA), Fall/Winter 1984-1985 - Vol. 3, Nos. 3-4 (last accessed: 22 August 2016).