Machine Identification Code

A Machine Identification Code (MIC), also known as printer steganography, yellow dots, tracking dots or secret dots, is a digital watermark which certain color laser printers and copiers leave on every single printed page, allowing to identify the device with which a document was printed and giving clues to the originator. Developed by Xerox and Canon in the mid-1980s, its existence became public only in 2004. In 2018, scientists developed privacy software to anonymize prints in order to support whistleblowers publishing their work.

History

In the mid-1980s Xerox pioneered an encoding mechanism for a unique number represented by tiny dots spread over the entire print area. Xerox developed the machine identification code "to assuage fears, that their color copiers could be used to counterfeit bills" [1] and received U.S. Patent No 5515451 describing the use of the yellow dots to identify the source of a copied or printed document.[2]

In October 2004, consumers first heard of the hidden feature, which enabled Dutch authorities to track down counterfeiters who had used a Canon color laser printer.[3]

In November 2004, PC World broke the news that this machine identification code had been used for decades in some printers, allowing "law enforcement to identify and track down counterfeiters".[1] The Central Bank Counterfeit Deterrence Group (CBCDG) has denied that it developed the feature.[2]

In 2005, the civil rights group Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) encouraged the public to send in sample printouts and subsequently decoded the pattern.[4] The pattern has been demonstrated on a wide range of printers from different manufacturers and models.[5] The EFF stated in 2015 that "the documents that we previously received through FOIA[6] suggested that all major manufacturers of color laser printers entered a secret agreement with governments to ensure that the output of those printers is forensically traceable. [...] it is probably safest to assume that all modern color laser printers do include some form of tracking information that associates documents with the printer's serial number."[7]

In 2007, the European Parliament was asked about the question of invasion of privacy,[8] since a color print bears the unique fingerprint of a laser printer, and allows tracking the buyer and owner especially when paid for electronically.[2]

Technical aspects

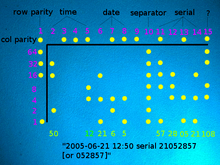

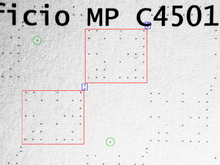

The mark consists of a dot-matrix spread. The yellow dots can barely be seen with the naked eye. They have a diameter of a tenth of a millimeter (1⁄250 in) and a spacing of about one millimeter (3⁄64 in). Their arrangement contains the serial number of the device, date and time of the printing and data to correct mistakes. For example, if the code consists of 8 × 16 dots in a square or hexagonal pattern, it spreads over a surface of about 4 square centimetres (0.62 sq in) and appears on a sheet of size DIN-A4 paper about 150 times. Thus it can be analyzed even if fragments or excerpts are available. Some printers arrange yellow dots in seemingly random point clouds.

According to the Chaos Computer Club in 2005, color printers leave a mark in a matrix of 32 × 16 dots and thus can store 64 bytes of data (64×8).[9]

As of 2011, Xerox was one of the few manufacturers to draw attention to the marked pages, stating in a product description, "The digital color printing system is equipped with an anti-counterfeit identification and banknote recognition system according to the requirements of numerous governments. Each copy shall be marked with a label which, if necessary, allows identification of the printing system with which it was created. This code is not visible under normal conditions."[10]

In 2018, scientists at the TU Dresden analyzed the patterns of 106 printer models of 18 manufacturers and found four different encoding schemes.[11]

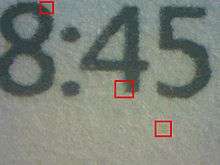

Visibility

The Machine Identification Code can be made visible by printing or copying a page and subsequent scanning of a small section with a scanner with high resolution. The yellow color channel can then be enhanced with a graphic program, to make any dots of the MIC clearly visible when present. Under good lighting conditions, a magnifying glass may be enough. Under UV-light the yellow dots are clearly recognizable.[12]

With this steganographic process, high-quality copies of an original (e.g. a bank note) under blue light have become identifiable. Using these markings even shredded prints can be restored: The "Shredder Challenge" in 2011 by the DARPA was only solved by the team of "All Your Shreds Are Belong To U.S." consisting of Otavio Good and two colleagues.[13][14]

Protection of privacy and circumvention

Copies or printouts of documents with confidential personal information, for example health care information, account statements, tax declaration or balance sheets, can be traced to the owner of the printer and when they were created. This traceability is unknown to many users and inaccessible, as manufacturers do not publicize the code. It is unclear which data are unintentionally passed on with a copy or printout. In particular, there are no hints in the support materials of most affected printers (exceptions see below). In 2005 Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) sought a decoding and made available a python script for analysis.[15]

In 2018, scientists from the TU Dresden developed and published a tool to extract and analyze the steganographic codes of a given color printer and subsequently to anonymize prints from that printer. The anonymization works by printing some additional yellow dots on top of the Machine Identification Code.[16][11][17] The scientists made software available which makes the code unreadable, because they want to support whistleblowers in their efforts to publicize grievances[18]

Comparable processes

Markings of other processes are not as easily recognizable as yellow dots. For example, a modulation of laser intensity and a variation of shades of grey in texts are already feasible. As of 2006, it was unknown whether manufacturers were using these techniques.[19]

See also

- EURion constellation, a dot matrix spread over a bank note, which stops printers and color copiers from processing.

References

- 1 2 Jason Tuohey. "Government Uses Color Laser Printer Technology to Track Documents". PC World. 22 November 2004.

- 1 2 3 Stephan Escher Tracking Dots unlesbar machen. Interview mit Uli Blumenthal Deutschlandfunk. 28 June 2018 (in German)

- ↑ Wilbert de Vries. "Dutch track counterfeits via printer serial numbers". PC World. 26 October 2004.

- ↑ "DocuColor Tracking Dot Decoding Guide". Electronic Frontier Foundation. 2005. Archived from the original on 5 March 2018. Retrieved 5 July 2018.

- ↑ Druckerliste die auf den Code untersucht wurden

- ↑ Lee, Robert (2005-07-27). "Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request" (PDF) (Letter). Letter to Latita M. Huff. Electronic Frontier Foundation. Retrieved 2016-11-07.

- ↑ "List of Printers Which Do or Do Not Display Tracking Dots". Electronic Frontier Foundation. Retrieved 11 March 2011.

- ↑ European Parliament Tracking codes in photocopiers and colour laser printers Parliamentary questions. 20 November 2007.

- ↑ Frank Rosengart (2005). "Datenspur Papier". Die Datenschleuder, Das wissenschaftliche Fachblatt für Datenreisende [technical factsheet] (PDF). Hamburg: Chaos Computer Club. pp. 19–21. ISSN 0930-1054. Retrieved 2011-02-27.

- ↑ "Abschnitt „Technische Daten des Digitalen Farbdrucksystems Xerox DocuColor 6060"". Xerox DocuColor® 6060 Digitales Farbdrucksystem (PDF; 1,4 MB) (Prospectus). Neuss: Xerox GmbH. p. 8. Retrieved 2011-02-27.

- 1 2 Richter, Timo; Escher, Stephan; Schönfeld, Dagmar; Strufe, Thorsten (2018-06-14). "Forensic Analysis and Anonymisation of Printed Documents". Proceedings of the 6th ACM Workshop on Information Hiding and Multimedia Security. ACM: 127–138. doi:10.1145/3206004.3206019. ISBN 9781450356251.

- ↑ "Beitrag bei Druckerchannel: Big Brother is watching you: Code bei Farblasern entschlüsselt". Druckerchannel.de.

- ↑ "CONGRATULATIONS to "All Your Shreds Are Belong To U.S."!". Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency. 2011-11-21. Retrieved 2014-06-12.

- ↑ "Tip for Bad Guys: Burn, Don't Shred". Bloomberg Businessweek. 2011-12-15. Retrieved 2014-06-12.

- ↑ "docucolor.cgi - CGI script to interpret Xerox DocuColor forensic dot pattern". Electronic Frontier Foundation. 2005. Archived from the original on 2017-05-08. Retrieved 2018-10-03.

- ↑ deda on GitHub

- ↑ "Dresdner Forscher überlisten Tracking-Punkte bei Laserdruckern". heise online (in German). 25 June 2018.

- ↑ So verpfeift dich dein Drucker nicht 26 June 2018. Deutschlandfunk Nova (in German)

- ↑ Printer Characterization and Signature Embedding for Security and Forensic Applications Pei-Ju Chiang, Aravind K. Mikkilineni, Sungjoo Suh, Jan P. Allebach, George T.-C. Chiu, Edward J. Delp., Purdue University, 2006 (poster)