Pope Leo III

| Pope Saint Leo III | |

|---|---|

| |

| Papacy began | 27 December 795 |

| Papacy ended | 12 June 816 |

| Predecessor | Adrian I |

| Successor | Stephen IV |

| Created cardinal | by Adrian I[1] |

| Personal details | |

| Birth name | Leone[1] |

| Born | Rome, Exarchate of Ravenna, Eastern Roman Empire |

| Died |

12 June 816 (aged 66) Rome, Papal States |

| Previous post | Cardinal-Priest of Santa Susanna (???-795) |

| Other popes named Leo | |

| Pope Saint Leo III | |

|---|---|

| |

| Pope | |

| Born | 750 |

| Died | 26 December 816 |

| Venerated in | Catholic Church |

| Canonized | 1669 by Pope Clement X |

| Feast | 12 June |

Pope Saint Leo III (Latin: Leo; fl. 12 June 816) was pope from 26 December 795[2] to his death in 816. Protected by Charlemagne from his enemies in Rome, he subsequently strengthened Charlemagne's position by crowning him Holy Roman Emperor and "Augustus of the Romans".

Leo was assaulted in Rome by partisans of the late Pope Adrian I, and fled to Charlemagne at Paderborn. The King of the Franks arbitrated the dispute, restoring Leo to his office. Leo subsequently crowned Charlemagne as Roman Emperor, which was not approved in Constantinople, although the Byzantines, occupied with their own defenses, were in no position to make much opposition.

Biography

Early life and pontifical selection

Leo was of a modest family in southern Italy, the son of Atyuppius and Elizabeth. At the time of his election he was Cardinal-Priest of Santa Susanna, and seemingly also vestiarius, or chief of the pontifical treasury, or wardrobe.[3]

He was elected on the very day his predecessor, Adrian I, was buried (26 December 795), and consecrated on the following day. It is quite possible that this haste may have been due to a desire on the part of the Romans to anticipate any interference of the Franks with their freedom of election. With the letter informing Charlemagne that he had been unanimously elected pope, Leo sent him the keys of the confession of St. Peter, and the standard of the city, and requested an envoy. This he did to show that he regarded the Frankish king as the protector of the Holy See.[3]

Pontificate

In return he received from Charlemagne letters of congratulation and a great part of the treasure which the king had captured from the Avars. The acquisition of this wealth enabled Leo to be a great benefactor to the churches and charitable institutions of Rome. While Charlemagne's letter is respectful and even affectionate, it also exhibits his concept of the coordination of the spiritual and temporal powers, nor does he hesitate to remind the pope of his grave spiritual obligations.[4] Charlemagne's reply stated that it was his function to defend the Church, and the function of the pope to pray for the realm and for the victory of his army.

Prompted by jealousy or ambition, or the thought that only someone of the nobility should hold the office of pope, a number of the relatives of Pope Adrian I formed a plot to render Leo unfit to hold his sacred office. On the occasion of the procession of the Greater Litanies (25 April 799), when the pope was making his way towards the Flaminian Gate, he was suddenly attacked by a body of armed men. He was dashed to the ground, and an effort was made to root out his tongue and tear out his eyes which left him injured and unconscious. He was rescued by two of the king's missi dominici, who came with a considerable force. The Duke of Spoleto sheltered the fugitive pope, who went later to Paderborn, where the king's camp then was.[4] He was received by the Frankish king with the greatest honour at Paderborn.[3] This meeting forms the basis of the epic poem Karolus Magnus et Leo Papa.

His enemies had accused Leo of adultery and perjury. Charlemagne ordered them to Paderborn, but no decision could be made. He then had Leo escorted back to Rome. In November 800, Charlemagne himself went to Rome, and on 1 December held a council there with representatives of both sides. Leo, on 23 December, took an oath of purgation concerning the charges brought against him, and his opponents were exiled.[3]

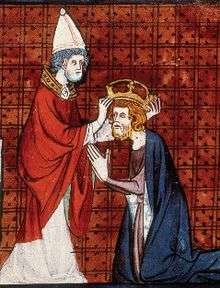

Coronation of Charlemagne

Charlemagne's father, Pepin the Short, defended the papacy against the Lombards and issued the Donation of Pepin, which granted the land around Rome to the pope as a fief. In 754 Pope Stephen II had conferred on Charles's father the dignity of Patricius Romanus, which implied primarily the protection of the Roman Church in all its rights and privileges; above all in its temporal authority which it had gradually acquired (notably in the former Byzantine Duchy of Rome and the Exarchate of Ravenna) by just titles in the course of the two preceding centuries.[4]

Two days after Leo's oath, on Christmas Day 800, he crowned Charlemagne as Roman emperor of the Holy Roman Empire. According to Charlemagne's biographer, Einhard, Charles had no suspicion of what was about to happen, and if informed would not have accepted the imperial crown.[5] On the other hand, there seems no reason to doubt that for some time previous the elevation of Charles had been discussed, both at home and at Rome, especially in view of two facts: the scandalous condition of the imperial government at Constantinople, and the acknowledged grandeur and solidity of the Carolingian house.[4] The coronation offended Constantinople, which had seen itself still as the rightful defender of Rome, but the Eastern Roman Empress Irene of Athens, like many of her predecessors since Justinian, was too weak to offer protection to the city or its much reduced citizenry.

In 808, Leo committed Corsica to Charlemagne for safe-keeping because of Muslim raids, originating from Al-Andalus,[6] on the island.[7] Nonetheless, Corsica, along with Sardinia, would still go on to be occupied by Muslim forces in 809 and 810.[8]

Significance

On Christmas Day in 800, Leo crowned Charlemagne Holy Roman Emperor at Old St. Peter's Basilica in Rome. Under Charlemange's leadership there arose a cultural enrichment still known as the Carolingian Renaissance. Charlemagne gathered to his court the cream of available intellect, centered on the scholar Alcuin, whom he brought from York in England. Monks and other copyists were set to transcribing ancient manuscripts, both classical and Christian, for the preservation and extension of learning. Schools were established at monasteries and cathedrals, the forerunners of the great universities. Myriad hymns and poems were composed, along with commentaries on Holy Scripture, treatises on music, theological works, and numerous chronicles of history.[9]

Leo helped restore King Eardwulf of Northumbria and settled various matters of dispute between the Archbishops of York and Canterbury.[3] He also reversed the decision of his predecessor Pope Adrian I in regards to the granting of the pallium to Hygeberht, Bishop of Lichfield. He believed that the English episcopate had been misrepresented before Adrian and that therefore his act was invalid. In 803, Lichfield was a regular diocese again.[10]

Leo forbade the addition of the filioque to the Nicene Creed, when asked to confirm the decision of a Council of Aachen held in 809. Although he approved of the doctrine expressed by the filioque, he also ordered that the Nicene Creed, without filioque, be displayed on silver tablets placed in Saint Peter's Basilica, adding: "Haec Leo posui amore et cautela orthodoxae fidei" ("I, Leo, put these here for love and protection of orthodox faith").[11]

The reasons for the coronation of Charlemagne, the involvement beforehand of the Frankish court, and the relationship to the Eastern Roman Empire are matters of debate among historians. An effective administrator of the papal territories, Leo contributed to the beautification of Rome.

Death and burial

Leo III died in 816 after a reign of more than 20 years. He was originally buried in his own monument. However, some years after his death, his remains were put into a tomb that contained the first four Popes Leo. In the 18th century, the relics of Leo I were separated from the other Leos, and he was given his own chapel.[12]

Canonization

Leo III was canonized by Pope Clement X, who, in 1673, had Leo's name entered in the Roman Martyrology.[13]

See also

References

- 1 2 Miranda, Salvador. "LEONE (?-816)". The Cardinals of the Holy Roman Church – Biographical Dictionary. Florida International University. Retrieved 2018-04-24.

- ↑ Pope Leo III at Encyclopædia Britannica

- 1 2 3 4 5

- 1 2 3 4

- ↑ Einhard (1880). "Charlemagne Crowned Emperor". The Life of Charlemagne. Translated by Turner, Samuel Epes. New York: Harper & Brothers.

- ↑ Raymond Davis (1 January 1995). The Lives of the Ninth-century Popes (Liber Pontificalis): The Ancient Biographies of Ten Popes from A.D. 817-891 (illustrated ed.). Liverpool University Press. p. 93. ISBN 9780853234791.

- ↑ Noble, Thomas F. X. (1 January 2011). The Republic of St. Peter: The Birth of the Papal State, 680-825. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 173. ISBN 9780812200911.

- ↑ Pirenne, Henri (7 March 2013). Mohammed and Charlemagne. Routledge. p. 160. ISBN 9781135030179.

- ↑ Reardon, Patrick Henry (2006). "Turning Point: The Crowning of Charlemagne". Christian History Biography. No. 89. Christian History Institute. Retrieved 24 April 2018.

- ↑

- ↑ "Agreed Statement of the North American Orthodox-Catholic Theological Consultation, 25 October 2003". United States Conference of Catholic Bishops. Archived from the original on 7 March 2012. Retrieved 23 April 2018.

- ↑ Reardon, Wendy (2012). The deaths of the Popes. McFarland. p. 41. ISBN 9781476602318.

- ↑ Baring-Gould, Sabine (1874). The Lives of the Saints. J. Hodges. p. 156. Retrieved 24 April 2018.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pope Leo III. |

- Translation of Einhard's Life of Charlemagne (c. 817–830, translated in 1880)

- Works by or about Pope Leo III in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

| Catholic Church titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Adrian I |

Pope 795–816 |

Succeeded by Stephen IV |