''Polaris'' expedition

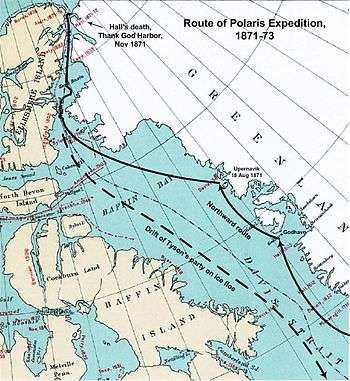

The Polaris expedition of 1871–1873 was led by the American Charles Francis Hall, who intended it to be the first expedition to reach the North Pole. Sponsored by the United States government, it was one of the first serious attempts at the Pole, after that of British naval officer William Edward Parry, who in 1827 reached 82°45'N. The expedition failed at its main objective being hampered by insubordination, incompetence, and poor leadership.

Under Hall's command, the Polaris departed from New York City in June 1871. By October, the men were wintering on the shore of northern Greenland, making preparations for the trip to the Pole. Hall returned to the ship from an exploratory sledging journey, and promptly fell ill. Before he died, he accused members of the crew of poisoning him. An exhumation of his body in 1968 revealed that he had ingested a large quantity of arsenic in the last two weeks of his life.

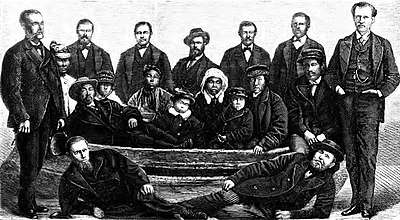

The expedition's notable achievement was reaching 82°29'N by ship, a record at the time. On the way southward, nineteen members of the expedition became separated from the ship and drifted on an ice floe for six months and 1,800 miles (2,900 km) before being rescued. The damaged Polaris was run aground and wrecked near Etah, Greenland, in October 1872. The remaining men were able to survive the winter, and were rescued the following summer. A naval board of inquiry investigated Hall's death, but no charges were ever laid.

Preparations

Origins

In 1827, William Edward Parry led a British Royal Navy expedition with the aim to be the first men to reach the North Pole.[1] In the 50 years following Parry's attempt, the Americans would mount three such expeditions: Elisha Kent Kane in 1853–55,[2] Isaac Israel Hayes in 1860–61,[3] and Charles Francis Hall with the Polaris in 1871–73.

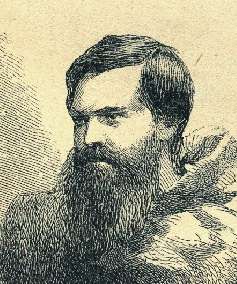

Hall had no special academic background or sailing experience—he was a blacksmith, engraver, then owner of a Cincinnati newspaper—but he was a voracious reader with an obsession for the Arctic.[4] After John Franklin's 1845 expedition was lost, Hall's focus was directed toward the Arctic. He was able to launch two expeditions in search of Franklin and his crew; one in 1860, and a second in 1864. These experiences established him as a seasoned Arctic explorer, and gave him valuable contacts among the Inuit people.[5] The renown he gained eventually allowed him to convince the United States government to fund his third expedition, an attempt on the North Pole.[6]

Finance and materiel

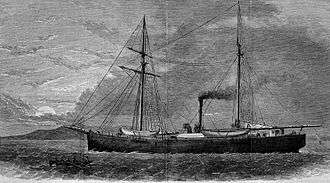

In 1870, a bill was introduced in the Senate to fund an expedition to the North Pole. Hall, aided by the Secretary of the Navy, George M. Robeson, successfully lobbied for, and received, a grant of $50,000 from Congress[7] to command the expedition and began recruiting personnel in late 1870.[8] He secured the Navy tugboat Periwinkle, a 387-ton screw-propelled steamer. At the Washington Navy Yard the ship was fitted as a fore-topsail schooner, and renamed Polaris.[9] She was prepared for Arctic service by the addition of solid oak timber all over her hull, and the bow was sheathed in iron. A new engine was added, and one of the boilers was retrofitted to burn seal or whale oil.[10]

The ship was also outfitted with four whaleboats, 20 feet (6.1 m) long and 4 feet (1.2 m) wide, and a flat-bottomed scow. During his previous Arctic expeditions, Hall came to admire the Inuit umiak—a type of open boat made of driftwood, whalebone, and walrus- or seal skins—and brought a similarly constructed collapsible boat which could hold 20 people.[11] Food packed on board consisted of tinned ham, salted beef, bread, and sailor's biscuit. The men intended to supplement their diet with fresh muskox, seal and polar bear, in order to ward off scurvy.[12]

Personnel

In July 1870, President Ulysses S. Grant had named Hall as overall commander of the expedition, but he was referred to as captain.[13] Although Hall had abundant Arctic experience, he had no sailing experience, and so the title was purely honorary.[14] In selecting the officers and seamen, Hall relied heavily on whalers with experience in the Arctic waters.[15] This was markedly different from the polar expeditions of the British Admiralty, who tended to use naval officers and highly disciplined crews.

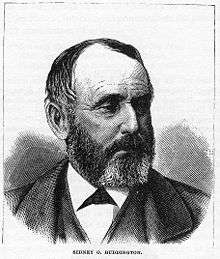

For his selection of sailing master, Hall first turned to Sidney O. Budington, then to George Tyson. Both initially declined due to prior whaling commitments. When those commitments fell through, Hall named Budington as sailing master and Tyson as assistant navigator.[14] Budington and Tyson had decades of experience captaining whaling vessels between the two of them. In effect, the Polaris now had three captains, a fact which would weigh heavily on the fate of the expedition. Further complicating matters, Budington and Hall had quarreled in 1863 during their earlier expedition in search of Franklin's lost expedition, when Budington had denied permission for Hall to bring his Inuit guides, Ebierbing and Tookoolito, who were ill and in Budington's care at the time.[16]

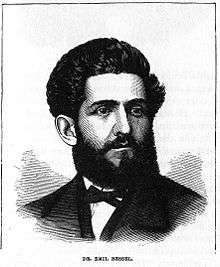

The rest of the crew was composed of Americans and Germans. First mate Hubbard Chester, second mate William Morton, and astronomer and chaplain R.W.D. Bryan were American. Chief engineer Emil Schumann, chief scientist and surgeon Emil Bessels were German, as were most of the seamen.[17] Meteorologist Frederick Meyer was a German-born sergeant in the US Army Signal Corps.[18] In addition to the 25 officers, crew, and scientific staff, Hall brought Inuit interpreter and hunter Ebierbing, his wife Tookoolito, and their child.[19] A Greenlandic aboriginal named Hans Hendrik, his wife Merkut and three children also joined the expedition.[20]

Expedition

New York to Upernavik

Even before leaving the Brooklyn Navy Yard on June 29, 1871, the expedition ran into personnel troubles. The cook, a seaman, a fireman, and assistant engineer deserted. The steward turned out to be a drunk, and was left in port.[21]

The ship stopped in New London, Connecticut, to pick up a replacement assistant engineer, and left on July 3, 1871. By the time the ship reached St. John's, there was dissension among the officers and scientific staff. Bessels, backed by Meyer, had openly rejected Hall's command over the scientific staff.[22][23] The dissension spread to the crew, which was divided by nationality.[24]

In his diary, Tyson wrote that by the time they reached Disko Island, "…expressions are freely made that Hall shall not get any credit out of this expedition. Already some have made up their minds how far they will go and when they will get home again."[25] Hall asked Captain Davenport of the supply ship Congress to intervene. Davenport threatened to have Meyer shackled for insubordination and sent back to the United States, at which point all of the Germans threatened to quit. Hall and Davenport were forced to back down, although Davenport delivered a strongly worded speech on naval discipline to the crew.[24]

In another open display of dissent, the ship's boilers had been tampered with by one of the crew. The special blubber-fired boilers had disappeared, apparently thrown overboard.[26]

On August 18, 1871, the ship reached Upernavik on Greenland's west coast, where they picked up Inuit hunter and interpreter Hans Hendrik. The Polaris proceeded north through Smith Sound and the Nares Strait, passing the previous furthest north by ship records held of Elisha Kane and Isaac Hayes.

Polar preparations and Hall's death

By September 2, 1871, the Polaris had reached her furthest north of 82°29'N.[27] Tension flared again as the three leading officers could not agree on whether to proceed any further. Hall and Tyson wanted to press north, to cut down the distance they would have to travel to the Pole by dogsled. Budington did not want to further risk the ship, and walked out on the discussion.[28] In the end, they sailed into Thank God Harbor (now called Hall Bay) on September 10, 1871, and anchored for the winter on the shore of northern Greenland.

Within a few weeks, Hall was making preparations for a sledding trip with the aim of beating William Parry's furthest north record.[27] Mistrust among the men in charge showed again when Hall told Tyson that "I cannot trust that man (Captain Budington). I want you to go with me, but don't know how to leave him alone with the ship."[27] There is some evidence that Budington may have been an alcoholic; on at least three occasions he raided the ship's stores, including the alcohol kept by the scientists for the preservation of specimens.[29] Hall had complained about Budington's drunken behavior,[30] and it fully came to light from the crew's testimony at the inquest following the expedition.[31]

With Tyson watching over the ship, Hall took two sleds with first mate Chester and the native guides Ebierbing and Hendrik, leaving on Oct 10, 1871. The day after leaving, Hall sent Hendrik back to the ship to retrieve a number of forgotten items. Hall also sent back a note to Bessels, reminding him to wind the chronometers at the right time every day. In his book Trial by Ice, Richard Parry postulated that such a note from the uneducated Hall must have rankled Bessels, who held a number of degrees from Stuttgart, Heidelberg, and Jena. It was another example of Hall's micromanagement of the expedition. Before he left on the overland trip, Hall gave Budington a detailed list of instructions regarding how to manage the ship in his absence.[32] This likely did not sit well with a sailing master with over 20 years of experience.

Upon their return on October 24, 1871, Hall suddenly fell ill after drinking a cup of coffee.[33] His symptoms started with an upset stomach, then progressed to vomiting and delirium the following day. Hall accused several of the ship's company, including Bessels, of having poisoned him.[33] Following these accusations, he refused medical treatment from Bessels, and drank only liquids delivered directly by his friend Tookoolito.[34] He seemed to improve for a few days and was even able to go up on deck.[35] Bessels had prevailed upon Bryan, the ship's chaplain, to convince Hall to allow the doctor to see him. By November 4, Hall relented, and Bessels resumed treatment. Shortly after, Hall's condition began to deteriorate, and he suffered vomiting and delirium, and collapsed.[36] Bessels diagnosed apoplexy, and Hall finally died on November 8. He was taken ashore and given a formal burial.

Attempt at North Pole

According to the protocol provided by Navy Secretary George M. Robeson, command of the expedition was turned over to Budington, under whom discipline further devolved.[37] The precious coal was being burned at a high rate: 6,334 pounds (2,873 kg) in November, which was 1,596 pounds (724 kg) more than the previous month,[38]and close to 8,300 pounds (3,800 kg) in December.[39] Budington was often seen to be drunk, but he was far from the only one to pilfer the alcohol stores; according to testimony at the Inquiry, Tyson was also seen "drunk like old mischief", and Schumann had gone so far as to make a duplicate of Budington's key so that he could help himself to alcohol as well.[40] Whatever the role of alcohol, it was clear that shipboard routine was breaking down; as Tyson remarked, "There is so little regularity observed. There is no stated time for putting out lights; the men are allowed to do as they please; and, consequently, they often make nights hideous by their carousing, playing cards to all hours."[41] For purposes unknown, Budington chose to issue the ship's supply of firearms to the crew.[42]

There is some evidence of a morally questionable plan being formulated among the senior officers that winter. On January 1, 1872, Tyson wrote in his diary: "Last month such an astonishing proposition was made to me that I have never ceased thinking of it since... It grew out of a discussion as to the feasibility of attempting to get farther north next summer."[43] And then on April 19, 1872: "Had a talk with Chester about the astounding proposition made to me in the winter. We agreed it was monstrous and must be prevented. Chester said he is determined, when he got home, to expose the matter."[43] Author Farley Mowat has suggested the officers were contemplating faking a journey to the Pole, or at least to a very high latitude.[44]

Whatever the unmentioned plan was, an expedition to try for the Pole was dispatched on June 6, 1872.[45] Chester led the expedition in a whaleboat, which was crushed by ice within a few miles of the Polaris. Chester and his men hiked back to the ship, and persuaded Budington to give them the collapsible boat.[46] With this boat and with Tyson piloting another whaleboat, the men set out to travel north again. In the meantime, the Polaris had found open water and was searching for a route south. Budington, not eager to spend another winter in the ice, sent Ebierbing north with orders for the Tyson and Chester: return to the ship at once.[47] The men were forced to abandon the boats and walk 20 miles (32 km) back to the Polaris. Now three of the ship's precious lifeboats were lost, and a fourth (the small scow) would be crushed by ice in July after being carelessly left out overnight. The expedition had failed in its main objective of reaching the North Pole.

Fate of the Polaris and journeys home

With the expedition's main goal abandoned, the Polaris turned south for home. In Smith Sound, west of the Humboldt Glacier, she ran aground on a shallow iceberg and could not be freed. On the night of October 15, 1872, with an iceberg threatening the ship, Schuman reported that water was coming in and the pumps could not keep up.[48] Budington ordered cargo to be thrown onto the ice to buoy the ship. Men began throwing goods overboard, as Tyson put it, "with no care taken as to how or where these things were thrown".[43] Much of the jettisoned cargo was lost.

A number of the crew were out on the surrounding ice during the night when a break-up of the pack occurred. When morning came, the group, consisting of Tyson, Meyer, six of the seamen, the cook, the steward, and all of the Inuit, found themselves stranded on an ice floe.[49] The castaways could see the Polaris 8 to 10 miles (13 to 16 km) away, but attempts to attract the ship's attention with a large black cloth were futile.

Resigned to the ice, the Inuit soon had igloo shelters built, and Tyson estimated that they had 1,900 pounds (860 kg) of food.[50] They also had the ship's two whaleboats, and two kayaks, although one kayak was soon lost during a breakup of the ice.[51] Meyer reckoned that they were drifting on the Greenland side of the Davis Strait and would soon be within rowing distance of Disko. He was incorrect; the men were actually on the Canadian side of the strait. The error caused the men to reject Tyson's plans for conserving. The seamen soon broke up one of the whaleboats for firewood, making a safe escape to land very unlikely.

One night in November, the men went on an eating binge, consuming a large quantity of the food stores.[50] The group drifted on the ice floe for the next six months over 1,800 miles (2,900 km)[52] before being rescued off the coast of Newfoundland by the sealer Tigress on April 30, 1873.[53] All probably would have perished had the group not included the skilled Inuit hunters Ebierbing and Hendrik,[54] who were able to kill seal on a number of occasions. Despite this, scarcely a word was written about the Inuit in either the official reports of the expedition, or the press, author Pierre Berton writes in The Arctic Grail.[55] However, this is disputed by Rear-Admiral Charles Henry Davis' Narrative of the North Polar Expeditions and author E. Vale Blake's Arctic Experiences, two contemporary accounts which frequently refer to the Esquimaux contribution to the castaways' survival.[56][57]

On October 16, with the ship's coal stores running low, Captain Budington decided to run the Polaris aground near Etah. Having lost much of their bedding, clothing, and food when it was haphazardly jettisoned from the ship on October 12, the remaining 14 men were in poor condition to face another winter. They built a hut from lumber salvaged from the ship, and on October 24, extinguished the ship's boilers to conserve coal. The bilge pumps stopped for good, and the ship heeled over on her side, half out of water.[58] Fortunately, the Etah Inuit helped the men survive the winter.[59] After wintering ashore, the crew built two boats from salvaged wood from the ship, and on June 3 the crew sailed south. They were spotted and rescued in July by the whaler Ravenscraig, and returned home via Scotland.[60]

Aftermath

Inquiry

On June 5, 1873, a United States Navy board of inquiry began. At this time, the crew and Inuit families had been rescued from the ice floe, however the fate of Budington, Bessels, and the remainder of the crew was still unknown. The board consisted of Admiral Goldsborough, Secretary of the Navy Robeson, Commodore Reynolds, Captain Howgate of the Army, and Spencer F. Baird of the Academy of Sciences.[61] Tyson was the first to appear for questioning, and related the friction between Hall, Budington, and Bessels, and Hall's deathbed accusations of poisoning.[62] The board also inquired about the whereabouts of Hall's journals and records. Tyson responded that while Hall was delirious, he instructed Budington to burn some of the papers, and the rest had disappeared.[63] Later, journals of other crew members were discovered at the site of the Polaris wreck, but these had the sections regarding Hall's death cut out.[64] Meyer testified to Budington's drinking, saying that the sailing master was "drunk most always while we were going southward".[65] Steward John Herron testified that he had not made the coffee that Hall had suspected of being laced with poison; he explained that the cook made the coffee, and that he had not kept track of how many people had touched the cup before it was brought to Hall.[66]

After Budington and the remainder of the crew were rescued and returned to the United States, the board of inquiry continued. Budington attacked Tyson's credibility, disputing Tyson's claim that he had obstructed Hall's efforts to sail the ship further north. He also disputed reports of his drinking, saying that he "[made] it a practice to drink but very little".[67] Bessels was questioned about Hall's cause of death. Bessels stated that "My idea of the cause of the first attack is that he had been exposed to very low temperature during the time that he was on the sledge journey. He came back and entered a warm cabin without taking off his heavy fur clothing, and then took a warm cup of coffee. And anyone knows what the consequences of that might be."[68] Bessels testified that Hall was "taken by hemiplegia", and his left arm and side were paralyzed, and that he had injected Hall with quinine to correct his elevated temperature before he died.[69]

Faced with conflicting testimony, lack of official records and journals, and no body for an autopsy, no charges were laid in connection with Hall's death. In the inquiry's final report, the surgeons general of the Army and Navy wrote: "From the circumstances and symptoms detailed by him, and comparing them with the medical testimony of all the witnesses, we are conclusively of the opinion that Captain Hall died from natural causes, viz., apoplexy; and that the treatment of the case by Dr. Bessel [sic] was the best practicable under the circumstances."[70]

Controversy

There has been speculation as to why Budington and the men aboard the Polaris did not attempt a rescue of those stranded on the ice floe. Tyson was perplexed as to why the ship could not see them 8 miles (13 km) distant, a group of men and supplies waving a dark-colored flag in a sea of white.[71] The day after the storm was clear and calm, and the men on the floe could see the ship was under both steam and sail. Aboard the ship, first mate Chester reported that he could see "provisions and stores" on a distant floe,[71] however there were never any orders to retrieve the stores or search for the castaways.

Budington's decision to beach the Polaris is equally controversial. Budington said that he "believed the propeller was smashed and the rudder broken".[72] The official report of the expedition states that the vessel should have been abandoned because "there was only coal enough to keep the fires alive for five days". However, the same report states that the propeller and rudder were in fact discovered to be intact after the ship was run aground, and the ship's boiler and sails were available.[72] Even if she ran out of coal, the ship was perfectly able to travel under sail alone. In defense of Budington's decision, when low tide exposed the ship's hull, the men found that the stem had completely broken away at the six-foot mark, taking iron sheeting and planking with it. Budington wrote in his journal that he "called the officer's attention to it, who only wondered she had kept afloat so long".[73]

Regarding Hall's fate, the official investigation that followed ruled the cause of death was apoplexy (an early term for stroke).[74] Some of Hall's symptoms—partial paralysis, slurred speech, delirium—certainly fit that diagnosis.[75] Indeed, the pains that Hall complained about down one side of his body, which he attributed to many years' huddling in an igloo, may have been due to a previous minor stroke.[76] However, in 1968, Hall's biographer Chauncey C. Loomis, a professor at Dartmouth College, made an expedition to Greenland to exhume Hall's body. Because of the permafrost, Hall's body, flag shroud, clothing and coffin were remarkably well-preserved. Tests on tissue samples of bone, fingernails and hair showed that Hall had received large doses of arsenic in the last two weeks of his life. Arsenic poisoning appears consistent with the symptoms party members reported: stomach pains, vomiting, stupor, and mania.[34] Arsenic can have a sweet taste, and Hall had complained that the coffee had tasted too sweet, and had burned his stomach.[77]

It also appears that at least three of the crew, Budington, Meyer, and Bessels, expressed relief at Hall's death and said that the expedition would be better off without him.[78] In his book The Arctic Grail, Pierre Berton suggests that it is possible that Hall accidentally dosed himself with the poison, as arsenic was common in medical kits of the time.[79] But it is considered more probable that he was murdered by one of the other members of the expedition, possibly Bessels, who was in nearly constant attendance of Hall. No charges were ever filed.[78]

Notes

- ↑ Berton 1988, pp. 97–102.

- ↑ Fleming 2011, pp. 10–49.

- ↑ Fleming 2011, pp. 62–78.

- ↑ Berton 1988, p. 345.

- ↑ Parry 2009, p. 15.

- ↑ Davis 1876, pp. 19–21.

- ↑ Davis 1876, p. 43.

- ↑ Mowat 1973, p. 113.

- ↑ Davis 1876, pp. 28–29.

- ↑ Parry 2009, pp. 24–27.

- ↑ Parry 2009, p. 26.

- ↑ Davis 1876, pp. 283–84.

- ↑ Grant 1870, p. 209.

- 1 2 Berton 1988, p. 384.

- ↑ Berton 1988, pp. 384–85.

- ↑ Parry 2009, pp. 30–31.

- ↑ Berton 1988, p. 385.

- ↑ Blake 1874, p. 130.

- ↑ Blake 1874, p. 117.

- ↑ Blake 1874, p. 146.

- ↑ Parry 2009, p. 48.

- ↑ Parry 2009, p. 51.

- ↑ Fleming 2011, p. 134.

- 1 2 Berton 1988, p. 387.

- ↑ Mowat 1973, p. 120.

- ↑ Parry 2009, p. 61.

- 1 2 3 Mowat 1973, p. 121.

- ↑ Berton 1988, p. 389.

- ↑ Blake 1874, p. 470.

- ↑ Parry 2009, p. 60.

- ↑ Parry 2009, pp. 269, 285.

- ↑ Parry 2009, p. 99.

- 1 2 Mowat 1973, p. 124.

- 1 2 Berton 1988, p. 390.

- ↑ Blake 1874, p. 162.

- ↑ Parry 2009, p. 115.

- ↑ Blake 1874, p. 341.

- ↑ Parry 2009, p. 133.

- ↑ Parry 2009, p. 139.

- ↑ Loomis 1971, p. 302.

- ↑ Parry 2009, pp. 133–34.

- ↑ Fleming 2011, p. 145.

- 1 2 3 Mowat 1973, p. 126.

- ↑ Mowat 1973, p. 135.

- ↑ Parry 2009, p. 155.

- ↑ Blake 1874, pp. 189–91.

- ↑ Parry 2009, p. 165.

- ↑ Berton 1988, p. 396.

- ↑ Parry 2009, pp. 199–200.

- 1 2 Berton 1988, p. 398.

- ↑ Davis 1876, pp. 526–27.

- ↑ Mowat 1973, p. 152.

- ↑ Davis 1876, p. 572.

- ↑ Berton 1988, p. 399.

- ↑ Berton 1988, p. 630.

- ↑ Davis 1876, pp. 523–54.

- ↑ Blake 1874, p. 241.

- ↑ Parry 2009, pp. 232–33.

- ↑ Mowat 1973, p. 155.

- ↑ Davis 1876, pp. 511–19.

- ↑ Parry 2009, p. 265.

- ↑ Blake 1874, p. 472.

- ↑ Parry 2009, pp. 266–67.

- ↑ Fleming 2011, p. 156.

- ↑ Parry 2009, p. 269.

- ↑ Parry 2009, p. 272.

- ↑ Parry 2009, p. 285.

- ↑ Parry 2009, p. 290.

- ↑ Parry 2009, pp. 291–92.

- ↑ Parry 2009, p. 293.

- 1 2 Mowat 1973, p. 133.

- 1 2 Mowat 1973, p. 154.

- ↑ Parry 2009, p. 211.

- ↑ Henderson 2001, p. 280.

- ↑ Henderson 2001, p. 85.

- ↑ Fleming 2011, p. 138.

- ↑ Fleming 2011, p. 140.

- 1 2 Berton 1988, p. 392.

- ↑ Berton 1988, pp. 380–92.

Bibliography

- Berton, P. F. (1988). The Arctic Grail: The Quest for the North West Passage and the North Pole. New York: Viking Press. ISBN 9780670824915.

- Blake, E. V. (1874). Arctic Experiences: a History of the Polaris Expedition. New York: Harper & Brothers. ISBN 9781333533168.

- Davis, C. H. (1876). Narrative of the North Polar Expedition of U.S. Ship Polaris. Washington D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office. ISBN 9781169374676.

- Fleming, F. H. (2011). Ninety Degrees North: The Quest for the North Pole. London: Granta Books. ISBN 9781847085436.

- Grant, U. S. (1870). The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant: November 1, 1869 – October 31, 1870. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press. ISBN 9780809319657.

- Henderson, B. B. (2001). Fatal North: Adventure and Survival Aboard USS Polaris. New York: New American Library. ISBN 9780451409355.

- Loomis, C. C. (1971). Weird and Tragic Shores: The Story of Charles Francis Hall, Explorer. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 9780375755255.

- Mowat, F. M. (1973). The Polar Passion: The Quest for the North Pole. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart. ISBN 9780771066214.

- Parry, R. L. (2009). Trial By Ice: The True Story of Murder and Survival on the 1871 Polaris Expedition. New York: Random House. ISBN 9780307492128.

External links

- Scrapbooks on the Polaris expedition held at the American Geographical Society Library, University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee