Penny

A penny is a coin (pl. pennies) or a unit of currency (pl. pence) in various countries. Borrowed from the Carolingian denarius (whence its former abbreviation d.), it is usually the smallest denomination within a currency system. Presently, it is the formal name of the British penny (abbr. p) and the informal name of one American cent (abbr. ¢) as well as the informal Irish designation of 1 cent euro coin (abbr. c). It is the informal name of the cent unit of account in Canada, although one cent coins are no longer minted there.[1] The name is also used in reference to various historical currencies also derived from the Carolingian system, such as the French denier and the German pfennig. It may also be informally used to refer to any similar smallest-denomination coin, such as the euro cent or Chinese fen.

The Carolingian penny was originally a .940-fine silver coin weighing 1/240 pound. It was adopted by Offa of Mercia and other English kings and remained the principal currency in Europe over the next few centuries until repeated debasements necessitated the development of more valuable coins. The British penny remained a silver coin until the expense of the Napoleonic Wars prompted the use of base metals in 1797. Despite the decimalization of currencies in the United States and, later, throughout the British Commonwealth, the name remains in informal use.

No penny is currently formally subdivided, although farthings (¼ d.), halfpennies, and half cents have previously been minted and the mill (1/10¢) remains in use as a unit of account in some contexts.

Name

Penny is first attested in a 1394 Scots text,[n 1] a variant of Old English peni, a development of numerous variations including pennig, penning, and pending.[n 2] The etymology of the term "penny" is uncertain, although cognates are common across almost all Germanic languages[n 3] and suggest a base *pan-, *pann-, or *pand- with the individualizing suffix -ing. Common suggestions include that it was originally *panding as a Low Franconian form of Old High German pfant "pawn" (in the sense of a pledge or debt, as in a pawnbroker putting up collateral as a pledge for repayment of loans); *panning as a form of the West Germanic word for "frying pan", presumably owing to its shape; and *ponding as a very early borrowing of Latin pondus ("pound").[3] Recently, it has been proposed that it may represent an early borrowing of Punic PN (Pane or Pene, "Face"), as the face of Carthaginian goddess Tanit was represented on nearly all Carthaginian currency.[4] Following decimalization, the British and Irish coins were marked "new penny" until 1982 and 1985, respectively.

The regular plural pennies fell out of use in England from the 16th century, except in reference to coins considered individually. It remains common in Scottish English and is standard for all senses in American English,[3] where, however, the informal "penny" is typically only used of the coins in any case, values being expressed in "cents".[5] The informal name for the American cent seems to have spread from New York State.[6]

In British English, prior to decimalization, values from two to eleven pence and of twenty pence are often written and spoken as a single word, as twopence or tuppence, threepence or thruppence, &c. (Other values were usually expressed in terms of shillings and pence or written as two words, which may or may not be hyphenated.) Where a single coin represented a number of pence, it was treated as a single noun, as a sixpence or two eightpences. Thus, "a threepence" would be single coin of that value whereas "three pence" would be its value and "three pennies" would be three penny coins. In British English, divisions of a penny were added to such combinations without a conjunction, as sixpence-farthing, and such constructions were also treated as single nouns. Adjectival use of such coins used the ending -penny, as sixpenny.[3]

The British abbreviation d. derived from the Latin denarius. It followed the amount after a space. It has been replaced since decimalization by p, usually written without a space or period. From this abbreviation, it is common to speak of pennies and values in pence as "p".[3] In North America, it is common to abbreviate cents with the currency symbol ¢. Elsewhere, it is usually written with a simple c.

History

Antiquity

The medieval silver penny was modeled on similar coins in antiquity, such as the Greek drachma, the Carthaginian shekel, and the Roman denarius. Forms of these seem to have reached as far as Norway and Sweden. The use of Roman currency in Britain seems to have fallen off after the Roman withdrawal and subsequent Saxon invasions.

Frankish Empire

Charlemagne's father Pepin the Short instituted a major currency reform around AD 755,[7] aiming to reorganise Francia's previous silver standard with a standardized .940-fine denier (Latin: denarius) weighing 1⁄240 pound.[8] (As the Carolingian pound seems to have been about 489.5 grams,[9][10] each penny weighted about 2 grams.) Around 790, Charlemagne introduced a new .950 or .960-fine penny with a smaller diameter. Surviving specimens have an average weight of 1.70 grams, although some estimate the original ideal mass at 1.76 grams.[11][12][13] Despite the purity and quality of these pennies, however, they were repeatedly rejected by traders throughout the Carolingian period in favor of the gold coins used elsewhere, a situation that led to repeated legislation against such refusal to accept the king's currency.[14]

England

| |

| O: Draped bust of Aethelred left. +ÆĐELRED REX ANGLOR | R: Long cross. +EADǷOLD MO CÆNT |

| Anglo-Saxon silver "Long Cross" penny of Aethelred II, moneyer Eadwold, Canterbury, c. 997–1003. The cross made cutting the coin into half-pennies or farthings (quarter-pennies) easier. (Note spelling Eadƿold in inscription, using Anglo-Saxon letter wynn in place of modern w.) | |

Some of the Anglo-Saxons kingdoms initially copied the solidus, the late Roman gold coin; at the time, however, gold was so rare and valuable that even the smallest coins had such a great value that they could only be used in very large transactions and were sometimes not available at all. Around AD 641–670, there seems to have been a movement to use coins with a lower gold content. This decreased their value and may have increased the number that could be minted, but these paler coins do not seem to have solved the problem of the value and scarcity of the currency. The miscellaneous silver sceattas minted in Frisia and Anglo-Saxon England after around 680 were probably known as "pennies" at the time. (The misnomer is based on a probable misreading of the Anglo-Saxon legal codes.)[15] Their purity varied and their weight fluctuated from about 0.8 to about 1.3 grams. They continued to be minted in East Anglia under Beonna and in Northumbria as late as the mid-9th century.

The first Carolingian-style pennies were introduced by King Offa of Mercia (r. 757–796), modeled on Pepin's system. His first series was 1⁄240 of the Saxon pound of 5400 grains (350 grams), giving a pennyweight of about 1.46 grams. His queen Cynethryth also minted these coins under her own name.[16] Near the end of his reign, Offa minted his coins in imitation of Charlemagne's reformed pennies. Offa's coins were imitated by East Anglia, Kent, Wessex and Northumbria, as well as by two Archbishops of Canterbury.[16] As in the Frankish Empire,[8] all these pennies notionally composed shillings (solidi; sol) and pounds (librae; livres) but during this period neither larger unit was minted. Instead, they functioned only as notional units of account.[17] (For instance, a "shilling" or "solidus" of grain was a measure equivalent to the amount of grain that 12 pennies could purchase.)[18] English currency was notionally .925-fine sterling silver at the time of Henry II, but the weight and value of the silver penny steadily declined from 1300 onwards.

In 1257, Henry III minted a gold penny which had the nominal value of 1 shilling eightpence (i.e., 20 d.). At first, the coin proved unpopular because it was overvalued for its weight; by 1265 it was so undervalued—the bullion value of its gold being worth 2 shillings (i.e., 24 d.) by then—that the coins still in circulation were almost entirely melted down for the value of their gold. Only eight gold pennies are known to survive.[19] It was not until the reign of Edward III that the florin and noble established a common gold currency in England.

.jpg)

The earliest halfpenny and farthing (¼d.) found date to the reign of Henry III. The need for small change was also sometimes met by simply cutting a full penny into halves or quarters. In 1527, Henry VIII abolished the Tower pound of 5400 grains, replacing it with the Troy pound of 5760 grains and establishing a new pennyweight of 1.56 grams, although, confusingly, the penny coin by then weighed about 8 grains, and had never weighed as much as this 24 grains. The last silver pence for general circulation were minted during the reign of Charles II around 1660. Since then, they have only been coined for issue as Maundy money, royal alms given to the elderly on Maundy Thursday.

United Kingdom

Throughout the 18th century, the British government did not mint pennies for general circulation and the bullion value of the existing silver pennies caused them to be withdrawn from circulation. Merchants and mining companies—such as Anglesey's Parys Mining Co.—began to issue their own copper tokens to fill the need for small change.[20] Finally, amid the Napoleonic Wars, the government authorized Matthew Boulton to mint copper pennies and twopences at Soho Mint in Birmingham in 1797.[21] Typically, 1 lb. of copper produced 24 pennies. In 1860, the copper penny was replaced with a bronze one (95% copper, 4% tin, 1% zinc). Each pound of bronze was coined into 48 pennies.[22]

United States

The United States' cent—popularly known as the "penny" since the early 19th century[6]—began with the unpopular copper chain cent in 1793.[23]

South Africa

The penny that was brought to the Cape Colony (in what is now South Africa) was a large coin — 36 mm in diameter, 3.3 mm thick and 1 oz (28 g) — and the twopence was correspondingly larger at 41 mm in diameter, 5 mm thick and 2 oz (57 g). On them was Britannia with a trident in her hand. The English called this coin the Cartwheel penny due to its large size and raised rim,[24] but the Capetonians referred to it as the Devil's Penny as they assumed that only the Devil used a trident.[25] The coins were very unpopular due to their large weight and size.[26] On 6 June 1825, Lord Charles Somerset, the governor, issued a proclamation that only British Sterling would be legal tender in the Cape (South Africa colony). The new British coins (which were introduced in England in 1816), among them being the shilling, six-pence of silver, the penny, half-penny, and quarter-penny in copper, were introduced to the Cape. Later two-shilling, four-penny, and three-penny coins were added to the coinage. The size and denomination of the 1816 British coins, with the exception of the four-penny coins, were used in South Africa until 1960.[25]

Criticism

Handling and counting penny coins entail transaction costs that may be higher than a penny. It has been claimed that, for micropayments, the mental arithmetic costs more than the penny. Changes in the price of metal commodity, combined with the continual debasement of paper currencies, causes the metal value of penny coins to exceed their face value.[27][28]

Australia and New Zealand adopted 5¢ and 10¢, respectively, as their lowest denomination,[29] followed by Canada, which adopted 5¢ as its lowest denomination in 2012.[30] Several nations have stopped minting equivalent value coins, and efforts have been made to end the routine use of pennies in several countries, including the United States.[31] In the UK, since 1992, one- and two-penny coins have been made from copper-plated steel (making them magnetic) instead of bronze.

In popular culture

- In British and American culture, finding a penny is traditionally considered lucky. A proverbial expression of this is "Find a penny, pick it up, and all the day you'll have good luck."[n 4]

- "A penny for your thoughts" is an idiomatic way of asking someone what they're thinking about. It is first attested in John Heywood's 1547 Dialogue Conteinying the Nomber in Effect of All the Proverbes in the Englishe Tongue,[33] at a time when the penny was still a sterling silver coin.

- The possibly related American expression "my two cents" (standing for "my humble opinion") uses the low-value denomination to depreciate the speaker's thoughts for the sake of humility or irony.

- In British English, to "spend a penny" means to urinate. Its etymology is literal: coin-operated public toilets commonly charged a predecimal penny, beginning with the Great Exhibition of 1851.

- Around Decimal Day, British Rail introduced the "Superloo", improved public toilets that charged 2p (roughly the equivalent of 6d.).[34]

- In 1936 U.S. shoemaker G.H. Bass & Co. introduced its "Weejuns" penny loafers. Other companies followed with similar products.

List of pennies

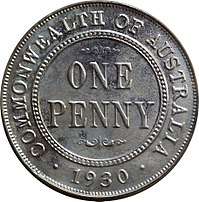

- Australia: penny (1911–1964) and cent (1966–1992)

- Bosnia and Herzegovina: pfenig (1998–present)

- Canada: cent (1858–2012)

- Denmark: penning (c. 830[35]–a. 1873)

- England: penny (c. 785–1707)

- Estonia: penn (1918-1927)

- Falkland Islands: Falkland Islands penny (1974–present)

- Finland: penni (1861–2002)

- France: denier (c. 755–1794)

- Various German states: pfennig (c. 755–2002) and euro cent (2002–present)

- Gibraltar: Gibraltar penny (1988–present)

- Guernsey, as an 8-double coin ("Guernsey penny", 1830–1921) and 1/240 of a Guernsey pound (1921–71) and 1/100 of a Guernsey pound (1971–present)

- Ireland: penny, as 1/240 Irish pound (1928-1968) and as 1/100 Irish pound (1971–2002), and euro cent (2002–present)

- Isle of Man: Manx penny (1668–present)

- Jersey: Jersey penny (1841–present)

- Netherlands: penning (8th–16th centuries)

- New Zealand: penny (1940–1967) and cent (1967–1987)

- Kingdom of Poland: fenig (1917–1918) and (1918-1924) during Second Polish Republic

- Norway: penning (c. 1000–1873)

- Saint Helena and Ascension Island: Saint Helena penny (1984–present)

- Scotland: Penny Scots/peighinn (c. 1130–1707)

- Sweden: penning (c. 1150–1548)

- South Africa: penny (1923–c. 1961) and cent (1961–2002)

- Transvaal: penny (1892–1900)

- United Kingdom: penny, as 1/240 British pound (1707–1970) and as 1/100 British pound (1971–present)

- United States: cent (1793–present)

- Medieval Wales: ceiniog (10th–13th centuries)

See also

Notes

- ↑ "He sal haf a penny til his noynsankys..."[2]

- ↑ The Oxford English Dictionary notes two families of variants, one comprising pæning, pending, peninc, penincg, pening, peningc, and Northumbrian penning and the other peneg, pennig, pænig, penig, penug, pæni, and peni, the later of which gave rise to the modern form.[3]

- ↑ Germanic cognates of penny include Dutch, Danish, Swedish, and Old Saxon penning and German: Pfennig in reference to the coin and Icelandic: peningur, Swedish pengar, and Danish: penge in reference to "money". Gothic, however, has skatts for the occurrence of "denarius" (Greek: δηνάριος, dēnários) in the New Testament.[3]

- ↑ This may be the source or a development of the "See a pin and pick it up, all the day you'll have good luck" recorded in a mid-19th century edition of Mother Goose.[32]

References

Citations

- ↑ "Canada's Last Penny Minted", CBC News .

- ↑ Slater, J. (1952), Early Scots Texts, Edinburgh: University of Edinburgh Press .

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "penny, n.", Oxford English Dictionary, 3rd ed., 2005 .

- ↑ Vennemann, Theo (2013). "Ne'er-a-Face: A Note on the Etymology of Penny, with an Appendix on the Etymology of Pane". In Patrizia Noel Aziz Hanna. Germania Semitica. Trends in Linguistics: Studies and Monographs, No. 259. Walter de Gruyter. p. 467. ISBN 978-3-11-030109-0. .

- ↑ The New Statesman, London: Statesman Publishing, 16 December 1966, p. 896 .

- 1 2 Constellation, 12 March 1831, p. 133 .

- ↑ Allen (2009).

- 1 2 Chown (1994), p. 23.

- ↑ Ferguson (1974), "Pound".

- ↑ Munro (2012), p. 31.

- ↑ Cipolla (1993), p. 129.

- ↑ Frassetto (2003), p. 131.

- ↑ NBB (2006).

- ↑ Suchodolski (1983).

- ↑ Bosworth & al.

- 1 2 Blackburn & al. (1986), p. 277.

- ↑ Keary (2005), p. xxii.

- ↑ Scott (1964), p. 40.

- ↑ "The Gold Penny", Coin and Bullion Pages .

- ↑ Selgin (2008), p. 16.

- ↑ "The Cartwheel Penny and Twopence of 1797", British Coinage, Royal Mint Museum, retrieved 15 May 2014 .

- ↑ EB (1911).

- ↑ "Timeline", Historian's Corner, Washington: US Mint .

- ↑ Severn Internet Services - www.severninternet.co.uk. "Birmingham Museums & Art Gallery Information Centre". BMAGiC. Retrieved 2011-12-22.

- 1 2 "South African History of Coins".

- ↑ "Currencyhelp.net". Currencyhelp.net. Retrieved 2011-12-22.

- ↑ Around the Nation; Treasurer Says Zinc Penny May Save $50 Million a Year, New York Times, 1 April 1981, retrieved 2009-05-07

- ↑ Hagenbaugh, Barbara (10 May 2006), Coins cost more to make than face value, USA Today, retrieved 2009-05-07

- ↑ "Article 2897480", Mytelus, archived from the original on 12 June 2008, retrieved 7 May 2009 .

- ↑ Smith, Joanna (30 March 2012), "Federal Budget 2012: Pennies to Be Withdrawn from Circulation", The Star, Toronto

- ↑ Lewis, Mark (5 July 2002). "Ban The Penny". Forbes. Retrieved 2009-05-07.

- ↑ Mother Goose's Chimes, Rhymes, & Melodies, H.B. Ashmead, c. 1861, retrieved 14 November 2009 .

- ↑ Corrado, John (11 October 2001), "What's the Origin of "A Penny for Your Thoughts"?", The Straight Dope, retrieved 13 February 2013 .

- ↑ "Spend a 6d in the superloo", Nation on Film, BBC, archived from the original on April 18, 2006 .

- ↑ Gullbekk, Svein H. (2014), "Vestfold: A Monetary Perspective on the Viking Age", Early Medieval Monetary History: Studies in Memory of Mark Blackburn, Studies in Early Medieval Britain and Ireland, Farnham: Ashgate, p. 343 .

Bibliography

- "Penny", Encyclopædia Britannica, 11th ed., Vol. XXI, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1911, pp. 115–116 .

- Allen, Larry (2009), "Carolingian Reform", The Encyclopedia of Money, Sta. Barbara: ABC Clio, pp. 59–60, ISBN 978-1-59884-251-7 .

- Blackburn, M.A.S.; et al. (1986), Medieval European Coinage, Vol. 1: The Early Middle Ages (5th–10th centuries), Cambridge .

- Bosworth; et al., An Old English Dictionary .

- Chown, John F (1994), A History of Money from AD 800, London: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-10279-0 .

- Cipolla, Carlo M. (1993), Before the Industrial Revolution: European Society and Economy, 1000-1700 .

- Ferguson, Wallace K. (1974), "Money and Coinage of the Age of Erasmus: An Historical and Analytical Glossary with Particular Reference to France, the Low Countries, England, the Rhineland, and Italy", The Correspondence of Erasmus: Letters 1 to 141: 1484 to 1500, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, pp. 311–349, ISBN 0-8020-1981-1 .

- Frassetto, Michael (2003), Encyclopedia of Barbarian Europe: Society in Transformation .

- Keary, Charles Francis (2005), A Catalogue of English Coins in the British Museum: Anglo-Saxon Series, Vol. I .

- Munro, John H. (2012), "The Technology and Economics of Coinage Debasements in Medieval and Early Modern Europe: With Special Reference to the Low Countries and England", Money in the Pre-Industrial World: Bullion, Debasements, and Coin Substitutes, Pickering & Chatto, republished 2016 by Routledge, pp. 30 ff, ISBN 978-1-84893-230-2 .

- Scott, Martin (1964), Medieval Europe, New York: Dorset Press, ISBN 0-88029-115-X .

- Islam and the Carolingian Penny, National Bank of Belgium Museum, November 2006 .

- Selgin, George A. (2008), Good Money: Birmingham Button Makers, the Royal Mint, and the Beginnings of Modern Coinage, 1775-1821, University of Michigan Press, ISBN 0-472-11631-2 .

- Suchodolski, Stanislaw (1983), "On the Rejection of Good Coin in Carolingian Europe", Studies in Numismatic Method: Presented to Philip Grierson, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 147–152, ISBN 0-521-22503-5 .

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Penny. |

- Copper Penny Importance – Blog post & video covering the importance of retaining copper pennies.

- The MegaPenny Project – A visualisation of what exponential numbers of pennies would look like.

- Silver Pennies – Pictures of English silver pennies from Anglo-Saxon times to the present.

- Copper Pennies – Pictures of English copper pennies from 1797 to 1860.

- US Lincoln Penny on the Planet Mars – Curiosity Rover (September 10, 2012).