Patients and public involvement (PPI)

Public involvement, or PI, is a UK National Health Service initiative to give lay people an effective, active role in health and care research. The term "health and care" covers healthcare (medical care), public health, and social care. The purpose is to align research more closely with patients' and the public’s needs, and thereby increase success and cost-effectiveness.

PI is the proper term for the involvement in research of anyone not professionally interested or experienced in health and care. Still sometimes used is PPI, patients' and public involvement. The bodies concerned, NIHR and INVOLVE (see below) have used PI rather than PPI since 2017, most notably in the draft Standards for Public Involvement in Research [1].

Origins and funding

Public involvement in UK health and care research is the last active remnant of the National Health Service Reform and Health Care Professions Act 2002 (Part 1, Section 5)[2]. The Act set up a Commission for Patient and Public Involvement in Health with a remit to move towards lay people's involvement in all aspects of health and care. The Commission had no funding, however, and closed in 2008. The Commission was replaced with a structure of 151 'Local involvement networks'; these had good funding and much the same aims - but were themselves abolished in 2013.

The UK's major funder of health and care research is the state-funded National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) - the research arm of the National Health Service and Europe's biggest health and care research funder. There are corresponding but subordinate organisations in Northern Ireland, Wales and Scotland. NIHR claims to “[involve] patients and the public in all our work”.[3] In the context of lay involvement, however, the most important organisation in the UK is an offshoot of NIHR called 'INVOLVE'. One of the aims of this advisory body is “to support active public involvement in NHS, public health and social care research”.[4]

A number of key British medical bodies, such as the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) [5] and Medical Research Council [6], have adopted formal policies for public involvement.

The mention of the UK's National Health Service has led many to believe there need be public involvement only in state-funded health and care research. As at 2017 most - if not all - charities involved in UK health and care research have active public involvement staff and committees, with hundreds or even thousands of PI volunteers. For instance, Parkinson's UK says "Everything we do [in research] is driven by people affected by Parkinson's." [7] These charities in particular have increasing interest in lay involvement with commercial research.

Even so, as yet there is meaningful public involvement in only a small proportion of health and care research.

That's mainly because, however much good will there may be, PI is still very new and uncoordinated, and any organisation wanting to take it on effectively needs a large number of volunteers.

Other relevant public sector organisations in the UK are:

- The regulatory Health Research Authority (HRA), whose home page[8] says "we involve patients and the public in [our] work to improve health research design, delivery and regulation."

- The Medical Research Council (MRC), which has an Ethics regulation and public involvement committee.[9]

Despite NIHR’s example and INVOLVE’s support, there are many different models of lay involvement in health and care research. Increasingly, public involvement in research is expected and even demanded by those funding it. PI is anticipated at all stages, including working on initial grant proposals, ethics committee review and final dissemination of outcomes.[10]

The 'patient' in PI

The word “patient” appears explicitly in PPI, and remains implicit in PI. This is because it is known that involving people in research about a specific health condition or care situation who have (or have had) direct first-hand experience will demonstrably improves that research.[11] Therefore, “patient” has come to mean: patients and ex-patients, as well as carers, ex-carers and relatives of patients.

The 'public' in PI

Public here refers to those lay people who do not necessarily have any direct stake in the research itself, but may have a particular interest in the outcomes of that research or who volunteer in the health and/or care sectors. Professionals such as doctors, nurses, care-home staff and medical researchers have plenty of opportunity to be involved in research so are explicitly excluded from public involvement in this context.[12]

The charity Parkinson’s UK has a national Involvement Steering Group and a number of regional ones. One of the members’ roles is to “look for opportunities to raise the profile of Parkinson’s UK as leaders in involvement”.[13]

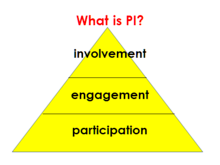

Levels of involvement

Lay people can have a role in health / care research in three broad levels. (This classification[14] follows the eight-rung ladder of citizen participation.[15])

- Participation - the most common levels, where research happens on or to people (whether as patients or controls). Participation in research appears as the broad base of the triangle shown. This is because most people with a role in health or care research are participants.

- Engagement - where researchers communicate and describe their work to lay people. This can happen in many ways. For example, if research is not yet complete, a research team may describe their thinking, progress and interim finding. If research is complete, the team may report to a public audience or disseminate findings by press release. Even plays have been put on to explain serious medical issues to lay audiences.[16]

- Involvement - where lay people have an active role and close contact with the research team. INVOLVE says “public involvement in research [is] research being carried out ‘with’ or ‘by’ members of the public rather than ‘to’, ‘about’ or ‘for’ them.”[17]

There may be hundreds of volunteers in an involvement group or network, with several central full-time staff and / or volunteers working to make them an effective team. For instance, the Alzheimer's Society Research Network (founded nearly twenty years ago) has some 300 volunteer members and xxx staff facilitators; the website [18] lists some fifteen roles for the PI people. The Society spends over £10 million a year on funding research studies; the Network costs about £xxx a year (including some commercial sponsorship).

Reporting

Despite the increased demand for public involvement in health research and care research, concerns have been expressed at the variable quality of feedback coming from that involvement. In 2017 new guidance was provided in an attempt to address this issue.[19][20] At around the same time, NIHR published the draft PI standards mentioned at the start of this article.

Involvement in the research cycle

Apart from cost, there are few reasons why all stages of health and care research should not involve lay people. NIHR’s PPI Framework 2015-2018 states: “We ensure that processes are in place to involve the public in all stages of the research we fund and manage … guaranteeing the involvement of patients, carers and members of the public at all points in the research process.”[21] In any event, effective PI can lead to more effective research and that should save money.

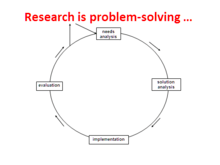

Broadly speaking, research – of any kind, not just for health or care – is problem-solving. Once a problem is precisely defined, solving it uses the problem-solving cycle. The research cycle shown is the same as that. (Scientific method has much more detail.)

Needs analysis (or problem analysis) is that first stage of defining precisely the problem to be researched: the research question. The next stage – which can take months – is to define precisely the apparently best and most appropriate solution: the research method.

Implementation is the main part of the cycle – carrying out the research. This may take a couple of years.

When that is over, the research team should evaluate the outcomes. This means checking with care that they have solved the problem, ie answered the research question asked. There can be many reasons for failing at this stage. In scientific research (science) and inventing (technology), the people concerned go round and round the cycle until they succeed. In other words, they return to needs analysis to tweak the research question, then to solution analysis to tweak the research method, and so on. One of the problems with much of health and care research is that the study runs out of funded time so evaluation can be hasty, and re-cycling is left out. The team leaves the cycle top left and goes on to the stages of reporting and disseminating. Or not, if the study failed to meet its objectives (or even came up with the "wrong" answers). There are many causes of research failure....

One of the benefits of lay involvement is to help the team obtain and maintain focus and to help ensure they carry out the different stages well. This can reduce the chance of failure and make the research more effective and more cost-effective.

A recent study of Parkinson's UK lay involvement[22] made those points clearly.

In practice, the research cycle has many more stages than the four in the sketch above. Quite possibly, in some studies, there are some stages for which there is no sign of public involvement in any context. (This is the case despite some organisations claiming PI in words like "at all stages of the research process".)

Here follow three lists of PI in the stages of research; some appear in the list of those most common here.

References

- ↑ "Standards for Public Involvement in Research" (PDF). NIHR. 15 June 2017. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- ↑ "National Health Service Reform and Health Care Professions Act 2002". www.legislation.gov.uk.

- ↑ "NIHR - National Institute for Health Research". www.nihr.ac.uk.

- ↑ http://www.invo.org.uk/. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ "Patient and public involvement policy". NICE. Retrieved 2017-12-20.

- ↑ "Patient and public involvement". Medical Research Council. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- ↑ "Research". Parkinson's UK. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- ↑ "Homepage". Health Research Authority.

- ↑ MRC, Medical Research Council, (18 July 2016). "Ethics, Regulation & Public Involvement Committee (ERPIC)". www.mrc.ac.uk.

- ↑ "Patient and Public Involvement". www.ucl.ac.uk. Retrieved 2017-12-20.

- ↑ Brett, Jo; Staniszewska, Sophie; Mockford, Carole; Herron-Marx, Sandra; Hughes, John; Tysall, Colin; Suleman, Rashida (2014-10-01). "Mapping the impact of patient and public involvement on health and social care research: a systematic review". Health Expectations. 17 (5): 637–650. doi:10.1111/j.1369-7625.2012.00795.x. ISSN 1369-7625. PMC 5060910.

- ↑ "Lay (lay person) – INVOLVE". www.invo.org.uk.

- ↑ "Parkinson's UK - Your Network". www.parkinsons.org.uk.

- ↑ "Briefing note two: What is public involvement in research? – INVOLVE". www.invo.org.uk.

- ↑ (PDF) http://www.participatorymethods.org/sites/participatorymethods.org/files/Arnstein%20ladder%201969.pdf. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Rawling, Jennie (8 December 2017). "Surgical mistakes explored on stage". Imperial College London. Retrieved 20 December 2017.

- ↑ "Briefing note two: What is public involvement in research? – INVOLVE". www.invo.org.uk. Retrieved 2017-12-20.

- ↑ "The Research Network". Alzheimer's Society. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- ↑ Staniszewska, S.; Brett, J.; Simera, I.; Seers, K.; Mockford, C.; Goodlad, S.; Altman, D. G.; Moher, D.; Barber, R. "GRIPP2 reporting checklists: tools to improve reporting of patient and public involvement in research". Research Involvement and Engagement. 3 (1). doi:10.1186/s40900-017-0062-2.

- ↑ "New guidance for reporting patient and public involvement in research - On Medicine". On Medicine. 2017-08-02. Retrieved 2017-12-20.

- ↑ (PDF) https://www.nihr.ac.uk/about-us/documents/NETSCC/PPI/PPI%20Framework.pdf. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ "The impact of involvement on researchers: a learning experience". 2017.

Further reading

- University College London Hospitals: How patients have helped us with our research

- National Standards for Public Involvement in Research website