Organizational communication

In communication studies, organizational communication is the study of communication within organizations. The flow of communication could be either formal or informal.

History

The field traces its lineage through business information, business communication, and early mass communication studies published in the 1930s through the 1950s. Until then, organizational communication as a discipline consisted of a few professors within speech departments who had a particular interest in speaking and writing in business settings. The current field is well established with its own theories and empirical concerns distinct from other fields.

Several seminal publications stand out as works broadening the scope and recognizing the importance of communication in the organizing process, and in using the term "organizational communication". Nobel Laureate Herbert A. Simon wrote in 1947 about "organization communications systems", saying communication is "absolutely essential to organizations".[1]:208 W. Charles Redding played a prominent role in the establishment of organizational communication as a discipline.

In the 1950s, organizational communication focused largely on the role of communication in improving organizational life and organizational output. In the 1980s, the field turned away from a business-oriented approach to communication and became concerned more with the constitutive role of communication in organizing. In the 1990s, critical theory influence on the field was felt as organizational communication scholars focused more on communication's possibilities to oppress and liberate organizational members.

Early underlying assumptions

Some of the main assumptions underlying much of the early organizational communication research were:

- Humans act rationally. Some people do not behave in rational ways, they generally have no access to all of the information needed to make rational decisions they could articulate, and therefore will make unrational decisions, unless there is some breakdown in the communication process—which is common. Irrational people rationalize how they will rationalize their communication measures whether or not it is rational.

- Formal logic and empirically verifiable data ought to be the foundation upon which any theory should rest. All we really need to understand communication in organizations is (a) observable and replicable behaviors that can be transformed into variables by some form of measurement, and (b) formally replicable syllogisms that can extend theory from observed data to other groups and settings

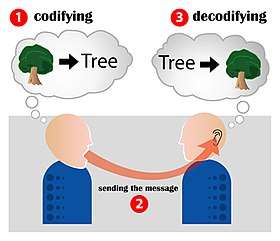

- Communication is primarily a mechanical process, in which a message is constructed and encoded by a sender, transmitted through some channel, then received and decoded by a receiver. Distortion, represented as any differences between the original and the received messages, can and ought to be identified and reduced or eliminated.

- Organizations are mechanical things, in which the parts (including employees functioning in defined roles) are interchangeable. What works in one organization will work in another similar organization. Individual differences can be minimized or even eliminated with careful management techniques.

- Organizations function as a container within which communication takes place. Any differences in form or function of communication between that occurring in an organization and in another setting can be identified and studied as factors affecting the communicative activity.

Herbert A. Simon introduced the concept of bounded rationality which challenged assumptions about the perfect rationality of communication participants. He maintained that people making decisions in organizations seldom had complete information, and that even if more information was available, they tended to pick the first acceptable option, rather than exploring further to pick the optimal solution.

In the early 1990s Peter Senge developed new theories on organizational communication. These theories were learning organization and systems thinking. These have been well received and are now a mainstay in current beliefs toward organizational communications.

Communication networks

Networks are another aspect of direction and flow of communication. Bavelas has shown that communication patterns, or networks, influence groups in several important ways. Communication networks may affect the group's completion of the assigned task on time, the position of the de facto leader in the group, or they may affect the group members' satisfaction from occupying certain positions in the network. Although these findings are based on laboratory experiments, they have important implications for the dynamics of communication in formal organizations.

There are several patterns of communication, such as "chain", "wheel", "star", "all-channel" network, and "circle".[2]

Interorganization communication

Flow nomenclature

Abbreviations are used to indicate the two-way flow of information or other transactions, e.g. B2B is "business to business". Duplex point-to-point communication systems, computer networks, non-electronic telecommunications, and meetings in person are all possible with the use of these terms. Examples:

|

|

|

Interpersonal communication

One-to-one or interpersonal communication between individuals may take several forms- messages may be verbal (that is, expressed in words), or non-verbal such as gestures, facial expressions, and postures ("body language"). Nonverbal messages may even stem from silence.[3]

Managers do not need answers to operate a successful business; they need questions. Answers can come from anyone, anytime, anywhere in the world thanks to the benefits of all the electronic communication tools at our disposal. This has turned the real job of management into determining what it is the business needs to know, along with the who/what/where/when and how of learning it. To effectively solve problems, seize opportunities, and achieve objectives, questions need to be asked by managers—these are the people responsible for the operation of the enterprise as a whole.[4]

Ideally, the meanings sent are the meanings received. This is most often the case when the messages concern something that can be verified objectively. For example, "This piece of pipe fits the threads on the coupling." In this case, the receiver of the message can check the sender's words by actual trial, if necessary. However, when the sender's words describe a feeling or an opinion about something that cannot be checked objectively, meanings can be very unclear. "This work is too hard" or "Watergate was politically justified" are examples of opinions or feelings that cannot be verified. Thus they are subject to interpretation and hence to distorted meanings. The receiver's background of experience and learning may differ enough from that of the sender to cause significantly different perceptions and evaluations of the topic under discussion. As we shall see later, such differences form a basic barrier to communication.[3]

Nonverbal content always accompanies the verbal content of messages. When speaking about nonverbal communication, Birdwhistell says "it is complementary to (meaning "adds to") rather than redundant with (or repeating of) the verbal behavior". For example, if someone is talking about the length of an object, they may hold out their hands to give a visual estimate of it.[5] This is reasonably clear in the case of face-to-face communication. As Virginia Satir has pointed out, people cannot help but communicate symbolically (for example, through their clothing or possessions) or through some form of body language. In messages that are conveyed by the telephone, a messenger, or a letter, the situation or context in which the message is sent becomes part of its non-verbal content. For example, if the company has been losing money, and in a letter to the production division, the front office orders a reorganization of the shipping and receiving departments, this could be construed to mean that some people were going to lose their jobs — unless it were made explicitly clear that this would not occur.[6]

A number of variables influence the effectiveness of communication. Some are found in the environment in which communication takes place, some in the personalities of the sender and the receiver, and some in the relationship that exists between sender and receiver. These different variables suggest some of the difficulties of communicating with understanding between two people. The sender wants to formulate an idea and communicate it to the receiver. This desire to communicate may arise from his thoughts or feelings or it may have been triggered by something in the environment. The communication may also be influenced by the relationship between the sender and the receiver, such as status differences, a staff-line relationship, or a learner-teacher relationship.[6]

Whatever its origin, information travels through a series of filters, both in the sender and in the receiver, and is affected by different channels, before the idea can be transmitted and re-created in the receiver's mind. Physical capacities to see, hear, smell, taste, and touch vary between people, so that the image of reality may be distorted even before the mind goes to work. In addition to physical or sense filters, cognitive filters, or the way in which an individual's mind interprets the world around him, will influence his assumptions and feelings. These filters will determine what the sender of a message says, how he says it, and with what purpose. Filters are present also in the receiver, creating a double complexity that once led Robert Louis Stevenson to say that human communication is "doubly relative". It takes one person to say something and another to decide what he said.[7]

Physical and cognitive, including semantic filters (which decide the meaning of words) combine to form a part of our memory system that helps us respond to reality. In this sense, March and Simon compare a person to a data processing system. Behavior results from an interaction between a person's internal state and environmental stimuli. What we have learned through past experience becomes an inventory, or data bank, consisting of values or goals, sets of expectations and preconceptions about the consequences of acting one way or another, and a variety of possible ways of responding to the situation. This memory system determines what things we will notice and respond to in the environment. At the same time, stimuli in the environment help to determine what parts of the memory system will be activated. Hence, the memory and the environment form an interactive system that causes our behavior. As this interactive system responds to new experiences, new learnings occur which feed back into memory and gradually change its content. This process is how people adapt to a changing world.[7]

Formal and informal

Informal and formal communication are used in an organization. Communication flowing through formal channels are downward, horizontal and upward whereas communication through informal channels are generally termed as grapevine.

Informal communication, generally associated with interpersonal, horizontal communication, was primarily seen as a potential hindrance to effective organizational performance. This is no longer the case. Informal communication has become more important to ensuring the effective conduct of work in modern organizations.

Grapevine is a random, unofficial means of informal communication. It spreads through an organization with access to individual interpretation as gossip, rumors, and single-strand messages. Grapevine communication is quick and usually more direct than formal communication. An employee who receives most of the grapevine information but does not pass it onto others is known as a dead-ender. An employee that receives less than half of the grapevine information is an isolate. Grapevine can include destructive miscommunication, but it can also be beneficial from allowing feelings to be expressed, and increased productivity of employees.

Top-down approach: This is also known as downward communication. This approach is used by the top level management to communicate to the lower levels. This is used to implement policies, guidelines, etc. In this type of organizational communication, distortion of the actual information occurs. This could be made effective by feedbacks.

Additionally, McPhee and Zaug (1995)[8] take a more nuanced view of communication as constitutive of organizations (also referred to as CCO). They identify four constitutive flows of communication, formal and informal, which become interrelated in order to constitute organizing and an organization:

- organizational self-structuring

- membership negotiation

- activity coordination

- institutional positioning.

Perspectives

Shockley-Zalabak identified the following two perspectives, essentially as ways of understanding the organizational communication process as a whole.[9]:26

The functional tradition

According to Shockley-Zalabak, the functional tradition is "a way of understanding organizational communication by describing what messages do and how they move through organizations." There are different functions within this process that all work together to contribute to the overall success of the organization, and these functions occur during the repetition of communication patterns in which the members of the organization engage in.[9]:28 The first types of functions are message functions which are "What communication does or how it contributes to the overall functioning of the organization", and we describe message functions in three different categories which are organizational functions, relationship functions, and change functions.[9]:30–31 Organizing functions as Shockley-Zalabak states, are "Messages that establish the rules and regulations of a particular environment". These messages can include items such as newsletters or handbooks for a specific organization, that individuals can read to learn the policies and expectations for a certain company.[9]:31 Relationship functions are "Communication that helps individuals define their roles and assess the compatibility of individual and organizational goals". These relationship functions are a key aspect to how individuals identify with a company and it helps them develop their sense of belonging which can greatly influence their quality of work.[9]:31–32 The third and final subcategory within message functions are change functions, which are defined as "messages that help organizations adapt what they do and how they do it". Change messages occur in various choice making decisions, and they are essential to meet the employee's needs as well as have success with continual adaptations within the organization.[9]:32

The meaning centered approach

According to Shockley-Zalabak, the meaning centered approach is "a way of understanding organizational communication by discovering how organizational reality is generated through human interaction". This approach is more concerned with what communication is instead of why and how it works, and message functions as well as message movement are not focused on as thoroughly in this perspective.[9]:38

Research

Research methodologies

Historically, organizational communication was driven primarily by quantitative research methodologies. Included in functional organizational communication research are statistical analyses (such as surveys, text indexing, network mapping and behavior modeling). In the early 1980s, the interpretive revolution took place in organizational communication. In Putnam and Pacanowsky's 1983 text Communication and Organizations: An Interpretive Approach. they argued for opening up methodological space for qualitative approaches such as narrative analyses, participant-observation, interviewing, rhetoric and textual approaches readings) and philosophic inquiries.

In addition to qualitative and quantitative research methodologies, there is also a third research approach called mixed methods. "Mixed methods is a type of procedural approach for conducting research that involves collecting, analyzing, and mixing quantitative and qualitative data within a single program of study. Its rationale postulates that the use of both qualitative and quantitative research provides a better and richer understanding of a research problem than either traditional research approach alone provides."[10]:42 Complex contextual situations are easier to understand when using a mixed methods research approach, compared to using a qualitative or quantitative research approach. There are more than fifteen mixed method design typologies that have been identified.[10]:42 Because these typologies share many characteristics and criteria, they have been classified into six different types. Three of these types are sequential, meaning that one type of data collection and analysis happens before the other. The other three designs are concurrent, meaning both qualitative and quantitative data are collected at the same time.[10]:43

Sequential explanatory design

To achieve results from a sequential explanatory design, researchers would take the results from analyzing quantitative data and get a better explanation through a qualitative follow up. They then interpret how the qualitative data explains the quantitative data.[10]:43

Sequential exploratory design

Although sequential exploratory design may resemble sequential explanatory design, the order in which data is collect is revered. Researchers being with collecting qualitative data and analyzing it, then follow up by building on it through a quantitative research method. They use the results from qualitative data to form variables, instruments and interventions for quantitative surveys and questionnaires.[10]:44

Sequential transformative design

Researchers in line with sequential transformative design are led by a "theoretical perspective such as a conceptual framework, a specific ideology, or an advocacy position and employs what will best serve the researcher's theoretical or ideological perspective".[10]:44 Therefore, with this research design, it could be either the qualitative or quantitative method that is used first and priority depends on circumstance and resource availability, but can be given to either.[10]:44

Concurrent triangulation design

With a concurrent triangulation design, although data is collected through both quantitative and qualitative methods at the same time, they are collected separately with equal priority during one phase. Later, during the analysis phase, the mixing of the two methods takes place.[10]:45

Concurrent embedded design

In a concurrent embedded design, again, both qualitative and quantitative data is collected, although here one method supports the other. Then, one of the two methods (either qualitative or quantitative) transforms into a support for the dominant method.[10]:45

Concurrent transformative design

The concurrent transformative design allows the researcher to be guided by their theoretical perspective, so their qualitative and quantitative data may have equal or unequal priority. Again, they are both collected during one phase.[10]:45

Mixed methods capitalizes on maximizing the strengths of qualitative and quantitative research and minimizing their individual weaknesses by combining both data.[10] Quantitative research is criticized for not considering contexts, having a lack of depth and not giving participants a voice. On the other hand, qualitative research is criticized for smaller sample sizes, possible researcher bias and a lack of generalizability.[10]

During the 1980s and 1990s critical organizational scholarship began to gain prominence with a focus on issues of gender, race, class, and power/knowledge. In its current state, the study of organizational communication is open methodologically, with research from post-positive, interpretive, critical, postmodern, and discursive paradigms being published regularly.

Organizational communication scholarship appears in a number of communication journals including but not limited to Management Communication Quarterly, Journal of Applied Communication Research, Communication Monographs, Academy of Management Journal, Communication Studies, and Southern Communication Journal.

Current research topics

In some circles, the field of organizational communication has moved from acceptance of mechanistic models (e.g., information moving from a sender to a receiver) to a study of the persistent, hegemonic and taken-for-granted ways in which we not only use communication to accomplish certain tasks within organizational settings (e.g., public speaking) but also how the organizations in which we participate affect us.

These approaches include "postmodern", "critical", "participatory", "feminist", "power/political", "organic", etc. and adds to disciplines as wide-ranging as sociology, philosophy, theology, psychology, business, business administration, institutional management, medicine (health communication), neurology (neural nets), semiotics, anthropology, international relations, and music.

Currently, some topics of research and theory in the field are:

Constitution, e.g.,

- how communicative behaviors construct or modify organizing processes or products

- how communication itself plays a constitutive role in organizations

- how the organizations within which we interact affect our communicative behaviors, and through these, our own identities

- structures other than organizations which might be constituted through our communicative activity (e.g., markets, cooperatives, tribes, political parties, social movements)

- when does something "become" an organization? When does an organization become (an)other thing(s)? Can one organization "house" another? Is the organization still a useful entity/thing/concept, or has the social/political environment changed so much that what we now call "organization" is so different from the organization of even a few decades ago that it cannot be usefully tagged with the same word – "organization"?

Narrative, e.g.,

- how do group members employ narrative to acculturate/initiate/indoctrinate new members?

- do organizational stories act on different levels? Are different narratives purposively invoked to achieve specific outcomes, or are there specific roles of "organizational storyteller"? If so, are stories told by the storyteller received differently from those told by others in the organization?

- in what ways does the organization attempt to influence storytelling about the organization? under what conditions does the organization appear to be more or less effective in obtaining a desired outcome?

- when these stories conflict with one another or with official rules/policies, how are the conflicts worked out? in situations in which alternative accounts are available, who or how or why are some accepted and others rejected?

Identity, e.g.,

- who do we see ourselves to be, in terms of our organizational affiliations?

- do communicative behaviors or occurrences in one or more of the organizations in which we participate effect changes in us? To what extent do we consist of the organizations to which we belong?

- is it possible for individuals to successfully resist organizational identity? what would that look like?

- do people who define themselves by their work-organizational membership communicate differently within the organizational setting than people who define themselves more by an avocational (non-vocational) set of relationships?

- for example, researchers have studied how human service workers and firefighters use humor at their jobs as a way to affirm their identity in the face of various challenges.[11] Others have examined the identities of police organizations, prison guards, and professional women workers.

Interrelatedness of organizational experiences, e.g.,

- how do our communicative interactions in one organizational setting affect our communicative actions in other organizational settings?

- how do the phenomenological experiences of participants in a particular organizational setting effect changes in other areas of their lives?

- when the organizational status of a member is significantly changed (e.g., by promotion or expulsion) how are their other organizational memberships affected?

- what kind of future relationship between business and society does organizational communication seem to predict?

Power e.g.,

- How does the use of particular communicative practices within an organizational setting reinforce or alter the various interrelated power relationships within the setting? Are the potential responses of those within or around these organizational settings constrained by factors or processes either within or outside of the organization – (assuming there is an "outside")?

- Do taken-for-granted organizational practices work to fortify the dominant hegemonic narrative? Do individuals resist/confront these practices, through what actions/agencies, and to what effects?

- Do status changes in an organization (e.g., promotions, demotions, restructuring, financial/social strata changes) change communicative behavior? Are there criteria employed by organizational members to differentiate between "legitimate" (i.e., endorsed by the formal organizational structure) and "illegitimate" (i.e., opposed by or unknown to the formal power structure) behaviors? When are they successful, and what do we mean by "successful" when there are "pretenders" or "usurpers" who employ these communicative means?

See also

Associations

References

- ↑ Simon, Herbert A. (1997) [1947]. Administrative Behavior: A Study of Decision-Making Processes in Administrative Organizations (4th ed.). New York: Free Press. ISBN 0684835827. OCLC 35159347.

- ↑ Summarized from concepts developed by Alex Bavelas, "Communication Patterns in Task-Oriented Groups," pp. 503–11; Harold Guetzkow, "Differentiation of Roles in Task-Oriented Groups," pp. 512–26, in Cartwright and Zander, Group Dynamics; H.J. Leavitt, "Some Effects of Certain Communication Patterns on Group Performance," Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology vol.

- 1 2 Richard Arvid Johnson (1976). Management, systems, and society : an introduction. Pacific Palisades, Calif.: Goodyear Pub. Co. pp. 148–142. ISBN 9780876205402. OCLC 2299496.

- ↑ Terry, J. F. (2008). The Art of Asking: Ask Better Questions, Get Better Answers. FT Press.

- ↑ Birdwhistell, Ray L. (1970). Kinesics and Context: Essays on Body Motion Communication. Philadelphia: University of Pensilvania Press. p. 181.

- 1 2 Virginia Satir (1967). Conjoint family therapy; a guide to theory and technique. Palo Alto, Calif.: Science and Behavior Books. pp. 76–81. OCLC 187068.

- 1 2 James G March; Herbert A Simon (1958). Organizations. New York: Wiley. pp. 9–11. ISBN 9780471567936. OCLC 1329335.

- ↑ McPhee, R.; Zaug, P. (2000). "The Communicative Constitution of Organizations: A framework for explanation". Electronic Journal of Communication/La Revue Electronique de Communication. 10 (1–2): 1–16.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Shockley-Zalabak, Pamela S. (2015). Fundamentals of Organizational Communication (9th ed.). United States of America: Pearson.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Abeza, Gashaw; O'Reilly, Norm; Dottori, Mark; Séguin, Benoit; Nzindukiyimana, Ornella (January 2015). "Mixed methods research in sport marketing". International Journal of Multiple Research Approaches. 9 (1): 40–56. doi:10.1080/18340806.2015.1076758.

- ↑ Tracy, S.J.; K. K. Myers; C. W. Scott (2006). "Cracking Jokes and Crafting Selves: Sensemaking and Identity Management Among Human Service Workers". Communication Monographs. 73 (3): 283–308. doi:10.1080/03637750600889500.

- Aamodt, Michael. Industrial/Organizational Psychology: An Applied Approach (8th ed.). Cengage learning. pp. 405–407.

- Lorette, Kristie. "The Importance of the Grapevine in Internal Business Communications". chron.com. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

Further reading

- Cheney, G., Christensen, L.T., Zorn, T.E., and Ganesh, S. 2004. Organizational Communication in an Age of Globalization: Issues, Reflections, Practices." Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press.

- Ferguson, S. D., & Terrion, J. L. (2014). Communication in Everyday Life: Personal and Professional Contexts. Oxford University Press.

- Gergen, Kenneth and Tojo Joseph. 1996. "Psychological Science in a Postmodern Context." American Psychologist. October 2001. Vol. 56. Issue 10. p803-813

- May, Steve and Mumby, Dennis K. 2005. "Engaging Organizational Communication Theory and Research." Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Redding, W. Charles. 1985. "Stumbling Toward Identity: The Emergence of Organizational Communication as a Field of Study" in McPhee and Tompkins, Organizational Communication: Traditional Themes and New Directions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.