Oracle bone

| Oracle bone | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

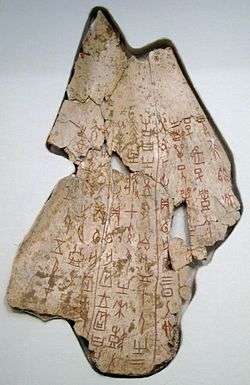

A Shang dynasty oracle bone from the Shanghai Museum | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 甲骨 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Literal meaning | Shells and bones | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Oracle bones (Chinese: 甲骨; pinyin: jiǎgǔ) are pieces of ox scapula or turtle plastron, which were used for pyromancy – a form of divination – in ancient China, mainly during the late Shang dynasty. Scapulimancy is the correct term if ox scapulae were used for the divination; plastromancy if turtle plastrons were used.

Diviners would submit questions to deities regarding future weather, crop planting, the fortunes of members of the royal family, military endeavors, and other similar topics.[1] These questions were carved onto the bone or shell in oracle bone script using a sharp tool. Intense heat was then applied with a metal rod until the bone or shell cracked due to thermal expansion. The diviner would then interpret the pattern of cracks and write the prognostication upon the piece as well.[2]. Pyromancy with bones continued in China into the Zhou dynasty, but the questions and prognostications were increasingly written with brushes and cinnabar ink, which degraded over time.

The oracle bones bear the earliest known significant corpus of ancient Chinese writing[lower-alpha 1] and contain important historical information such as the complete royal genealogy of the Shang dynasty.[lower-alpha 2] When they were discovered and deciphered in the early twentieth century, these records confirmed the existence of the Shang, which some scholars had until then doubted.

Discovery

The Shang-dynasty oracle bones are thought to have been unearthed periodically by local farmers[9] since as early as the Sui and Tang dynasties and perhaps starting as early as the Han dynasty,[10] but local inhabitants did not realize what the bones were and generally reburied them.[11] During the 19th century, villagers in the area digging in the fields discovered a number of bones and used them as "dragon bones" (Chinese: 龍骨; pinyin: lóng gǔ), a reference to the traditional Chinese medicine practice of grinding up Pleistocene fossils into tonics or poultices.[11][12] The turtle shell fragments were prescribed for malaria,[lower-alpha 3] while the other animal bones were used in powdered form to treat knife wounds.[13]

In 1899, an antiques dealer from Shandong Province searching for Chinese bronzes in the area acquired a number of oracle bones from locals, several of which he sold to Wang Yirong, the chancellor of the Imperial Academy in Beijing.[14] Wang was a knowledgeable collector of Chinese bronzes and is believed to be the first person in modern times to recognize the oracle bones' markings as ancient Chinese writing similar to that on Zhou dynasty bronzes.[14] A legendary tale relates that Wang was sick with malaria, and his scholar friend Liu E was visiting him and helped examine his medicine. They discovered, before it was ground into powder, that it bore strange glyphs, which they, having studied the ancient bronze inscriptions, recognized as ancient writing.[13] As Xǔ Yǎhuì states:

- "No one can know how many oracle bones, prior to 1899, were ground up by traditional Chinese pharmacies and disappeared into peoples' stomachs."[13]

It is not known how Wang and Liu actually came across these "dragon bones", but Wang is credited with being the first to recognize their significance.[13] Wang committed suicide in 1900 in connection with his involvement in the Boxer Rebellion, and his son later sold the bones to friend Liu E, who published the first book of rubbings of the oracle bone inscriptions in 1903.[14][15] News of the discovery of the oracle bones spread quickly throughout China and among foreign collectors and scholars, and the market for oracle bones exploded, though many collectors sought to keep the location of the bones' source a secret.[14] Although scholars tried to find their source, antique dealers falsely claimed that the bones came from Tangyin in Henan.[13] In 1908, scholar Luo Zhenyu discovered the source of the bones near Anyang and realized that the area was the site of the last Shang dynasty capital.[14]

Decades of uncontrolled digs followed to fuel the antiques trade,[lower-alpha 4] and many of these pieces eventually entered collections in Europe, the US, Canada and Japan.[16] The first Western collector was the American missionary Frank H. Chalfant (1862–1914).[lower-alpha 5] Chalfant also first coined the term "oracle bone" in his 1906 book Early Chinese Writing, which was then borrowed into Chinese as "jiǎgǔ 甲骨" in the 1930s.[18]

Only a small number of dealers and collectors knew the location of the source of the oracle bones or visited it until they were found by Canadian missionary James Menzies, the first person to scientifically excavate, study, and decipher them. He was the first to conclude that the bones were records of divination from the Shang dynasty, and was the first to come up with a method of dating them (in order to avoid being fooled by fakes). In 1917 he published the first scientific study of the bones, including 2,369 drawings and inscriptions and thousands of ink rubbings. Through the donation of local people and his own archaeological excavations, he acquired the largest private collection in the world, over 35,000 pieces. He insisted that his collection remain in China, though some were sent to Canada by colleagues who were worried that they would be either destroyed or stolen during the Japanese invasion of China in 1937.[19] The Chinese still acknowledge the pioneering contribution of Menzies as "the foremost western scholar of Yin-Shang culture and oracle bone inscriptions." His former residence in Anyang was declared a "Protected Treasure" in 2004, and the James Mellon Menzies Memorial Museum for Oracle Bone Studies was established.[20][21][22]

Official excavations

By the time of the establishment of the Institute of History and Philology headed by Fu Sinian at the Academia Sinica in 1928, the source of the oracle bones had been traced back to modern Xiǎotún (小屯) village at Anyang in Henan Province. Official archaeological excavations in 1928–1937 led by Li Ji, the father of Chinese archaeology,[23] discovered 20,000 oracle bone pieces, which now form the bulk of the Academia Sinica's collection in Taiwan and constitute about 1/5 of the total discovered.[lower-alpha 6] When deciphered, the inscriptions on the oracle bones turned out to be the records of the divinations performed for or by the royal household. These, together with royal-sized tombs,[lower-alpha 7] proved beyond a doubt for the first time the existence of the Shang dynasty, which had recently been doubted, and the location of its last capital, Yin. Today, Xiǎotún at Anyang is thus also known as the Ruins of Yin, or Yinxu.

The Jiǎgǔwén héjí (甲骨文合集) edited by Hu Houxuan, with its supplement edited by Peng Bangjiong, is the most comprehensive catalogue of oracle bone fragments. The 20 volumes contain reproductions of over 55,000 fragments. A separate work contains transcriptions of the inscriptions into standard characters.[25]

Dating

The vast majority of the inscribed oracle bones were found at the Yinxu site in modern Anyang, and date to the reigns of the last nine kings of the Shang dynasty.[26] The diviners named on the bones have been assigned to five periods by Dong Zuobin:[27]

| Period | Kings | Common diviners |

|---|---|---|

| I | Wu Ding[lower-alpha 8] | Què 㱿, Bīn 賓, Zhēng 爭, Xuān 宣 |

| II | Zu Geng, Zu Jia | Dà 大, Lǚ 旅, Xíng 行, Jí 即, Yǐn 尹, Chū 出 |

| III | Lin Xin, Kang Ding | Hé 何 |

| IV | Wu Yi, Wen Wu Ding | |

| V | Di Yi, Di Xin |

The kings were involved in divination in all periods, but in later periods most divinations were done personally by the king.[29] The extant inscriptions are not evenly distributed across these periods, with 55% coming from period I and 31% from periods III and IV.[30] A few oracle bones date to the beginning of the subsequent Zhou dynasty.

The earliest oracle bones (corresponding to the reigns of Wu Ding and Zu Geng) record dates using only the 60-day cycle of stems and branches, though sometimes the month was also given.[31] Attempts to determine an absolute chronology focus on a number of lunar eclipses recorded in inscriptions by the Bīn group, who worked during the reign of Wu Ding, possibly extending into the reign of Zu Geng. Assuming that the 60-day cycle continued uninterrupted into the securely dated period, scholars have sought to match the recorded dates with calculated dates of eclipses.[32] There is general agreement on four of these, spanning dates from 1198 to 1180 BCE.[32] A fifth is assigned by some scholars to 1201 BCE.[33] From these data, the Xia–Shang–Zhou Chronology Project, relying on the statement in the "Against Luxurious Ease" chapter of the Book of Documents that the reign of Wu Ding lasted 59 years, dated it from 1250 to 1192 BCE.[34][35] David Keightley argued that the "Against Luxurious Ease" chapter should not be treated as a historical text, because was composed much later, presents reign lengths as moral judgements, and gives other reign lengths that are contradicted by oracle bone evidence.[36] He dated the reign of Wu Ding as approximately from 1200 to 1181 BCE.[37] Ken-ichi Takashima dates the earliest oracle bone inscriptions to 1230 BCE.[38]

Period V inscriptions often identify numbered ritual cycles, making it easier to estimate the reign lengths of the last two kings.[39] The start of this period is dated 1100–1090 BCE by Keightley and 1101 BCE by the XSZ project.[37][35] Most scholars now agree that the Zhou conquest of the Shang took place close to 1046 or 1045 BCE, over a century later than the traditional date.[40][41][42]

Shang divination

Since divination (-mancy) was by heat or fire (pyro-) and most often on plastrons or scapulae, the terms pyromancy, plastromancy[lower-alpha 9] and scapulimancy are often used for this process.

Materials

The oracle bones are mostly tortoise plastrons (ventral or belly shells, probably female[lower-alpha 10]) and ox scapulae (shoulder blades), although some are the carapace (dorsal or back shells) of tortoises, and a few are ox rib bones,[lower-alpha 11] scapulae of sheep, boars, horses and deer, and some other animal bones.[lower-alpha 12] The skulls of deer, oxen and humans have also been found with inscriptions on them,[lower-alpha 13] although these are very rare and appear to have been inscribed for record keeping or practice rather than for actual divination;[43][lower-alpha 14] in one case, inscribed deer antlers were reported, but Keightley (1978) reports that they are fake.[44][lower-alpha 15] Neolithic diviners in China had long been heating the bones of deer, sheep, pigs and cattle for similar purposes; evidence for this in Liaoning has been found dating to the late fourth millennium BCE.[45] However, over time, the use of ox bones increased, and use of tortoise shells does not appear until early Shang culture. The earliest tortoise shells found that had been prepared for divinatory use (i.e., with chiseled pits) date to the earliest Shang stratum at Erligang (Zhengzhou, Henan).[46] By the end of the Erligang, the plastrons were numerous,[46] and at Anyang, scapulae and plastrons were used in roughly equal numbers.[47] Due to the use of these shells in addition to bones, early references to the oracle bone script often used the term "shell and bone script", but since tortoise shells are actually a bony material, the more concise term "oracle bones" is applied to them as well.

The bones or shells were first sourced and then prepared for use. Their sourcing is significant because some of them (especially many of the shells) are believed to have been presented as tribute to the Shang, which is valuable information about diplomatic relations of the time. We know this because notations were often made on them recording their provenance (e.g., tribute of how many shells from where and on what date). For example, one notation records that "Què (雀) sent 250 (tortoise shells)", identifying this as, perhaps, a statelet within the Shang sphere of influence.[48][49][lower-alpha 16] These notations were generally made on the back of the shell's bridge (called bridge notations), the lower carapace, or the xiphiplastron (tail edge). Some shells may have been from locally raised tortoises, however.[lower-alpha 17] Scapula notations were near the socket or a lower edge. Some of these notations were not carved after being written with a brush, proving (along with other evidence) the use of the writing brush in Shang times. Scapulae are assumed to have generally come from the Shang's own livestock, perhaps those used in ritual sacrifice, although there are records of cattle sent as tribute as well, including some recorded via marginal notations.[51]

Preparation

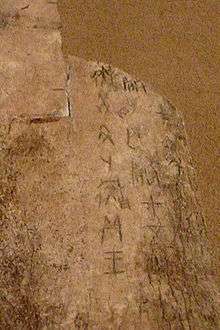

_-_BL_Or._7694.jpg)

The bones or shells were cleaned of meat and then prepared by sawing, scraping, smoothing and even polishing to create convenient, flat surfaces.[50][52][lower-alpha 18] The predominance of scapulae and later of plastrons is also thought to be related to their convenience as large, flat surfaces needing minimal preparation. There is also speculation that only female tortoise shells were used, as these are significantly less concave.[48] Pits or hollows were then drilled or chiseled partway through the bone or shell in orderly series. At least one such drill has been unearthed at Erligang, exactly matching the pits in size and shape.[53] The shape of these pits evolved over time and is an important indicator for dating the oracle bones within various sub-periods in the Shang dynasty. The shape and depth also helped determine the nature of the crack that would appear. The number of pits per bone or shell varied widely.

Cracking and interpretation

Divinations were typically carried out for the Shang kings in the presence of a diviner. A very few oracle bones were used in divination by other members of the royal family or nobles close to the king. By the latest periods, the Shang kings took over the role of diviner personally.[3]

During a divination session, the shell or bone was anointed with blood,[54] and in an inscription section called the "preface", the date was recorded using the Heavenly Stems and Earthly Branches, and the diviner name was noted. Next, the topic of divination (called the "charge") was posed,[lower-alpha 19] such as whether a particular ancestor was causing a king's toothache. The divination charges were often directed at ancestors, whom the ancient Chinese revered and worshiped, as well as natural powers and Dì (帝), the highest god in the Shang society. A wide variety of topics were asked, essentially anything of concern to the royal house of Shang, from illness, birth and death, to weather, warfare, agriculture, tribute and so on.[1] One of the most common topics was whether performing rituals in a certain manner would be satisfactory.[lower-alpha 20]

An intense heat source[lower-alpha 21] was then inserted in a pit until it cracked. Due to the shape of the pit, the front side of the bone cracked in a rough 卜 shape. The character 卜 (pinyin: bǔ or pǔ; Old Chinese: *puk; "to divine") may be a pictogram of such a crack; the reading of the character may also be an onomatopoeia for the cracking. A number of cracks were typically made in one session, sometimes on more than one bone, and these were typically numbered. The diviner in charge of the ceremony read the cracks to learn the answer to the divination. How exactly the cracks were interpreted is not known. The topic of divination was raised multiple times, and often in different ways, such as in the negative, or by changing the date being divined about. One oracle bone might be used for one session or for many,[lower-alpha 22] and one session could be recorded on a number of bones. The divined answer was sometimes then marked either "auspicious" or "inauspicious", and the king occasionally added a "prognostication", his reading on the nature of the omen.[56] On very rare occasions, the actual outcome was later added to the bone in what is known as a "verification".[56] A complete record of all the above elements is rare; most bones contain just the date, diviner and topic of divination,[56] and many remained uninscribed after the divination.[55]

The uninscribed divination is thought to have been brush-written with ink or cinnabar on the oracle bones or accompanying documents, as a few of the oracle bones found still bear their brush-written divinations without carving,[lower-alpha 23] while some have been found partially carved. After use, shells and bones used ritually were buried in separate pits (some for shells only; others for scapulae only),[lower-alpha 24] in groups of up to hundreds or even thousands (one pit unearthed in 1936 contained over 17,000 pieces along with a human skeleton).[57]

Archaeological evidence of pre-Anyang pyromancy

While the use of bones in divination has been practiced almost globally, such divination involving fire or heat has generally been found in Asia and the Asian-derived North American cultures.[58] The use of heat to crack scapulae (pyro-scapulimancy) originated in ancient China, the earliest evidence of which extends back to the 4th millennium BCE, with archaeological finds from Liaoning, but these were not inscribed.[45] In Neolithic China at a variety of sites, the scapulae of cattle, sheep, pigs and deer used in pyromancy have been found,[59] and the practice appears to have become quite common by the end of the third millennium BCE. Scapulae were unearthed along with smaller numbers of pitless plastrons in the Nánguānwài (南關外) stage at Zhengzhou, Henan; scapulae as well as smaller numbers of plastrons with chiseled pits were also discovered in the Lower and Upper Erligang stages.[60]

Significant use of tortoise plastrons does not appear until the Shang culture sites.[46] Ox scapulae and plastrons, both prepared for divination, were found at the Shang culture sites of Táixīcūn (台西村) in Hebei and Qiūwān (丘灣) in Jiangsu.[61] One or more pitted scapulae were found at Lùsìcūn (鹿寺村) in Henan, while unpitted scapulae have been found at Erlitou in Henan, Cíxiàn (磁縣) in Hebei, Níngchéng (寧城) in Liaoning, and Qíjiā (齊家) in Gansu.[62] Plastrons do not become more numerous than scapulae until the Rénmín (人民) Park phase.[63]

Oracle bones at other sites

Four inscribed bones have been found at Zhengzhou in Henan: three with numbers 310, 311 and 312 in the Hebu corpus, and one containing a single character (ㄓ) which also appears in late Shang inscriptions. HB 310, which contained two brief divinations, has been lost, but is recorded in a rubbing and two photographs. HB 311 and 312 each contain a short sentence similar to the late Shang script. HB 312 was found in an upper layer of the Erligang culture. The others were found accidentally in river management earthworks, and so lack archaeological context. Pei Mingxiang argued that they predated the Anyang site. Takashima, referring to character forms and syntax, argues that they were contemporaneous with the reign of Wu Ding.[64][65]

A few inscribed oracle bones have also been unearthed in the Zhōuyuán, the original political center of the Zhou in Shaanxi and in Daxinzhuang, Jinan, Shandong. Some bones from the Zhouyuan are believed to be contemporaneous with the reign of Di Xin, the last Shang king.[66]

Post-Shang oracle bones

After the founding of Zhou, the Shang practices of bronze casting, pyromancy and writing continued. Oracle bones found in the 1970s have been dated to the Zhou dynasty, with some dating to the Spring and Autumn period. However, very few of those were inscribed. It is thought that other methods of divination supplanted pyromancy, such as numerological divination using milfoil (yarrow) in connection with the hexagrams of the I Ching, leading to the decline in inscribed oracle bones. However, evidence for the continued use of plastromancy exists for the Eastern Zhou, Han, Tang[67] and Qing[68] dynasty periods, and Keightley mentions use in Taiwan as late as 1972.[69]

Notes

- ↑ A tiny number of isolated mid to late Shang pottery, bone and bronze inscriptions may predate the oracle bones. However, the oracle bones are considered the earliest significant body of writing, due to the length of the inscriptions, the vast amount of vocabulary (very roughly 4000 graphs), and the sheer quantity of pieces found – at least 100,000 pieces[3][4] bearing millions of characters,[5] and around 5,000 different characters,[5] forming a full working vocabulary (Qiu 2000, p. 50 cites various statistical studies before concluding that "the number of Chinese characters in general use is around five to six thousand"). It should be noted that there are also inscribed or brush-written Neolithic signs in China, but they do not generally occur in strings of signs resembling writing; rather, they generally occur singly and whether or not these constitute writing or are ancestral to the Shang writing system is currently a matter of great academic controversy. They are also insignificant in number compared to the massive amounts of oracle bones found so far.[6][7][8]

- ↑ Chou 1976, p. 12 cites two such scapulae, citing his own "商殷帝王本紀" Shāng–Yīn dìwáng bĕnjì, pp. 18–21.

- ↑ Xu 2002, pp. 4–5 cites The Compendium of Materia Medica and includes a photo of the relevant page and entry.

- ↑ Xu 2002, p. 6 cites eight waves of illegal digs over three decades, with tens of thousands of pieces taken.

- ↑ Rev. Chalfant acquired 803 oracle bone pieces between 1903 and 1908, and hand-traced over 2500 pieces including these.[17]

- ↑ over 100,000 pieces have been found in all.[3][4]

- ↑ Eleven royal-sized tombs were found.[24] This exactly matches the number of kings who should have been buried at Yin (the 12th king died in the Zhou conquest and would not have received a royal burial).

- ↑ Dong also included kings Pan Geng, Xiao Xin and Xiao Yi. However, few or perhaps no inscriptions can be reliably assigned to pre-Wu Ding reigns. Many scholars assume that earlier oracle bones from Anyang exist but have not yet been found.[28]

- ↑ According to Keightley 1978a, p. 5, citing Yang Junshi 1963, the term plastromancy (from plastron + Greek μαντεία, "divination") was coined by Li Ji.

- ↑ Keightley 1978a, p. 9 – the female shells are smoother, flatter and of more uniform thickness, facilitating pyromantic use.

- ↑ According to Chou 1976, p. 7, only four rib bones have been found.

- ↑ such as ox humerus or astragalus (ankle bone).[16]

- ↑ Xu 2002, p. 34 shows a large, clear photograph of a piece of inscribed human skull in the collection of the Institute of History and Philology at the Academia Sinica, Taiwan, presumably belonging to an enemy of the Shang.

- ↑ There appears to be some confusion in published reports between inscribed bones in general, and bones that have actually been heated and cracked for use in divination.

- ↑ Xu 2002, p. 35 does show an inscribed deer skull, thought to have been killed by a Shang king during a hunt.

- ↑ Some cattle scapulae were also tribute.[50]

- ↑ Keightley 1978a, p. 12 mentions reports of Xiǎotún villagers finding hundreds of shells of all sizes, implying live tending or breeding of the turtles onsite.

- ↑ Chou 1976, p. 12 notes that evidence of sawing is present on some oracle bones, and that the saws were likely of bronze, although none have ever been found.

- ↑ There is scholarly debate about whether the topic was posed as a question or not; Keightley prefers the term "charge", since grammatical questions were often not involved.

- ↑ For a fuller overview of the topics of divination and what can be gleaned from them about the Shang and their environment, see Keightley 2000.

- ↑ The nature of this heat source is still a matter of debate.

- ↑ Most full (non-fragmentary) oracle bones bear multiple inscriptions, the longest of which are around 90 characters long.[55]

- ↑ Qiu 2000, p. 60 mentions that some were written with a brush and either ink or cinnabar, but not carved.

- ↑ Those that were for practice or records, where buried in common rubbish pits.[57]

References

- 1 2 Keightley 1978a, pp. 33–35.

- ↑ Keightley 1978a, pp. 40–42.

- 1 2 3 Qiu 2000, p. 61.

- 1 2 Keightley 1978a, p. xiii.

- 1 2 Qiu 2000, p. 49.

- ↑ Qiu 2000.

- ↑ Boltz 2003.

- ↑ Woon 1987.

- ↑ Qiu 2000, p. 60.

- ↑ Chou 1976, p. 1, citing Wei Juxian 1939, "Qín-Hàn shi fāxiàn jiǎgǔwén shuō", in Shuōwén Yuè Kān, vol. 1, no.4; and He Tianxing 1940, "Jiǎgǔwén yi xianyu gǔdài shuō", in Xueshu (Shànghǎi), no. 1

- 1 2 Wilkinson 2000, p. 390.

- ↑ Fairbank & Goldman 2006, p. 33.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Xu 2002, p. 4.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Wilkinson (2000), p. 391.

- ↑ Xu 2002, p. 16.

- 1 2 Chou 1976, p. 1.

- ↑ Chou 1976, pp. 1–2.

- ↑ Wilkinson (2015), p. 681.

- ↑ York

- ↑ Wang Haiping (2006). "Menzies and Yin-Shang Culture Scholarship – An Unbreakable Bond." Anyang Ribao (Anyang Daily), August 12, 2006, p.1

- ↑ See Linfu Dong (2005). Cross Culture and Faith: the Life and Work of James Mellon Menzies. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, ISBN 978-0-8020-3869-2.

- ↑ Geoff York (2008). "The unsung Canadian some knew as 'Old Bones' James Mellon Menzies, a man of God whose faith inspired him to unearth clues about the Middle Kingdom." Globe and Mail, January 18, 2008, p. F4–5

- ↑ Xu 2002, p. 9.

- ↑ Xu 2002, p. 10.

- ↑ Wilkinson 2000, pp. 400–401.

- ↑ Keightley 1978a, pp. xiii, 139.

- ↑ Keightley 1978a, pp. 31, 92–93, 203.

- ↑ Keightley 1978a, pp. 97–98, 139–140, 203.

- ↑ Keightley 1978a, p. 31.

- ↑ Keightley 1978a, pp. 139–140.

- ↑ Keightley 1978a, pp. 113–116.

- 1 2 Keightley 1978a, p. 174.

- ↑ Zhang 2002, p. 353.

- ↑ Zhang 2002, pp. 352–354.

- 1 2 Li 2002, p. 331.

- ↑ Keightley 1978b, pp. 428–429.

- 1 2 Keightley 1978a, p. 228.

- ↑ Takashima 2012, p. 142.

- ↑ Keightley 1978a, pp. 116, 174–175.

- ↑ Keightley 1978a, pp. 226–228.

- ↑ Li 2002, pp. 328–330.

- ↑ Takashima 2012, pp. 142–143.

- ↑ Keightley 1978a, p. 7.

- ↑ Keightley 1978a, p. 7, note 21.

- 1 2 Keightley 1978a, p. 3.

- 1 2 3 Keightley 1978a, p. 8.

- ↑ Keightley 1978a, p. 10.

- 1 2 Keightley 1978a, p. 9.

- ↑ Xu 2002, p. 22.

- 1 2 Xu 2002, p. 24.

- ↑ Keightley 1978a, p. 11.

- ↑ Keightley 1978a, pp. 13–14.

- ↑ Keightley 1978a, p. 18.

- ↑ Xu 2002, p. 28, citing the Rites of Zhou.

- 1 2 Qiu 2000, p. 62.

- 1 2 3 Xu 2002, p. 30.

- 1 2 Xu 2002, p. 32.

- ↑ Keightley 1978a, pp. 3, 4, n. 11 and 12.

- ↑ Keightley 1978a, pp. 3, 6, n.16.

- ↑ Keightley 1978a, p. 8, note 25, citing KKHP 1973.1, pp. 70, 79, 88, 91, plates 3.1, 4.2, 13.8.

- ↑ Keightley 1978a, p. 8, note 25 cites KK 1973.2 p.74.

- ↑ Keightley 1978a, p. 6, n.16.

- ↑ Keightley 1978a, p. 8, note 25 cites Zhèngzhoū Èrlĭgāng, p.38.

- ↑ Takashima 2012, pp. 143–160.

- ↑ Qiu 2000, pp. 41–42.

- ↑ Takashima 2012, p. 141.

- ↑ Keightley 1978a, p. 4 n.4.

- ↑ Keightley 1978a, p. 9, n.30, citing Hu Xu 1782–1787, ch. 4, p.3b on use in Jiangsu

- ↑ cites Zhāng Guangyuan 1972

Works cited

- Boltz, William G. (2003). The origin and early development of the Chinese writing system. New Haven, CT: American Oriental Society. ISBN 0-940490-18-8. Pbk. ed. with minor corr. and a new preface.

- Chou, Hung-hsiang 周鴻翔 (1976). Oracle Bone Collections in the United States. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-09534-0.

- Fairbank, John King; Goldman, Merle (2006). China : a new history (2nd enl. ed.). Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-01828-1.

- Keightley, David N. (1978a). Sources of Shang history : the oracle-bone inscriptions of Bronze Age China. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-02969-0. Paperback 2nd edition (1985) ISBN 0-520-05455-5.

- ——— (1978b). "The Bamboo Annals and Shang-Chou Chronology". Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. 38 (2): 423–438. JSTOR 2718906.

- ——— (2000). The ancestral landscape: time, space, and community in late Shang China, ca. 1200–1045 B.C. Berkeley: University of California, Berkeley. ISBN 1-55729-070-9.

- Li, Xueqin (2002). "The Xia-Shang-Zhou Chronology Project: Methodology and Results". Journal of East Asian Archaeology. 4: 321–333. doi:10.1163/156852302322454585.

- Qiu, Xigui (2000). Chinese writing (Wenzixue gaiyao). Transl. by Gilbert L. Mattos and Jerry Norman. Berkeley: Society for the Study of Early China. ISBN 1-55729-071-7.

- Takashima, Ken-ichi (2012). "Literacy to the South and the East of Anyang in Shang China: Zhengzhou and Daxinzhuang". In Li, Feng; Branner, David Prager. Writing and Literacy in Early China: Studies from the Columbia Early China Seminar. University of Washington Press. pp. 141–172. ISBN 978-0-295-80450-7.

- Wilkinson, Endymion (2000). Chinese History: A Manual (2nd ed.). Harvard University Asia Center. ISBN 978-0-674-00249-4.

- ——— (2015). Chinese History: A New Manual (4th ed.). Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Asia Center. ISBN 978-0-674-08846-7.

- Woon, Wee Lee 雲惟利 (1987). Chinese Writing: Its Origin and Evolution. Macau: University of East Asia. Now issued by Joint Publishing, Hong Kong.

- Xu, Yahui (許雅惠 Hsu Ya-huei) (2002). Ancient Chinese Writing, Oracle Bone Inscriptions from the Ruins of Yin. English translation by Mark Caltonhill and Jeff Moser. Taibei: National Palace Museum. ISBN 978-957-562-420-0. Illustrated guide to the Special Exhibition of Oracle Bone Inscriptions from the Institute of History and Philology, Academia Sinica. Govt. Publ. No. 1009100250.

- York, Geoffrey. "The Unsung Canadian Some Knew as 'Old Bones'". The Globe and Mail. March 27, 2017. Retrieved February 18, 2017.

- Zhang, Peiyu (2002). "Determining Xia–Shang–Zhou Chronology through Astronomical Records in Historical Texts". Journal of East Asian Archaeology. 4: 335–357. doi:10.1163/156852302322454602.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Oracle bones. |

- Oracle bones, United College Library, Chinese University of Hong Kong. Includes 45 inscribed fragments.

- Oracle Bone Collection, Institute of History and Philology, Taipei City.

- High-resolution digital images of oracle bones, Cambridge Digital Library.

- Yīnxū shūqì 殷虛書契 by Luo Zhenyu – a collection of rubbings or oracle bone fragments.

- Guījiǎ shòugǔ wénzì 龜甲獸骨文字 by Hayashi Taisuke – another collection of rubbings.

- 四方风 or Winds of the Four Directions World Digital Library. National Library of China.