Open list

| Part of the Politics series |

| Electoral systems |

|---|

|

Plurality/majoritarian

|

|

|

|

Other systems & related theory |

|

|

Open list describes any variant of party-list proportional representation where voters have at least some influence on the order in which a party's candidates are elected. This as opposed to closed list, which allows only active members, party officials, or consultants to determine the order of its candidates and gives the general voter no influence at all on the position of the candidates placed on the party list. Additionally, an open list system allows voters to select individuals rather than parties. Different systems give voter different amounts of influence. Voter's choice is usually called preference vote.

Systems

Relatively closed

A "relatively closed" open list system is one where a candidate must get a full quota of votes on their own to be assured of winning a seat. (This quota, broadly speaking, is the total number of votes cast divided by the number of places to be filled. Usually the precise number required is the Hare quota, but the Droop quota can also be used.)

The total number of seats won by the party minus the number of its candidates that achieved this quota gives the number of unfilled seats. These are then successively allocated to the party's not-yet-elected candidates who were ranked highest on the original list.

More open

In a 'more open' list system, the quota for election could be lowered from the above amount. It is then (theoretically) possible that more of a party's candidates achieve this quota than the total seats won by the party. It should therefore be made clear in advance whether list ranking or absolute votes take precedence in that case.

Example: A party list got 5000 votes. If the quota is 1000 votes, then the party wins five seats.

| Candidate position on the list |

Preference votes | 25% of the quota | Elected |

|---|---|---|---|

| #1 | 3500 | x (first) | x |

| #2 | 50 | x | |

| #3 | 150 | x | |

| #4 | 250 | x (third) | x |

| #5 | 100 | ||

| #6 | 100 | ||

| #7 | 450 | x (second) | x |

| #8 | 50 | ||

| ... | ... | ||

Candidates #1, #7 and #4 have each achieved 25% of the quota (250 preference votes or more). They get the first three of the five seats the party has won. The other two seats will be taken by #2 and #3, the two highest remaining positions on the party list. This means that #5 is not elected even though being the fifth on the list and having more preference votes than #2.

In practice, at the national level only one or two candidates succeed to precede on their lists as 25% of the national quota means a huge number of votes. This happens more often at the local level where the quota (in absolute numbers of votes) is lower. Parties usually allow candidates to ask for preference votes, but without campaigning negatively against other candidates on the list.

A country could introduce a version of a more open list voting system allowing parties to choose a small number (say, 5 or 10) of candidates to be guaranteed to be selected first (perhaps to form a small 'core' of government, such as head of state, cabinet, etc.) This solves the problem of major party figures being prevented from taking office, yet still allows the vast majority of party candidates' order on the party list to be decided by the voters.

Austria

The members of the National Council are elected by open list proportional representation in nine multi-member constituencies based on the states (with varying in size from 7 to 36 seats) and 39 sub-constituencies. Voters are able to cast a party vote and one preference votes on each the federal, state and electoral district level for their preferred candidates within that party. The thresholds for a candidate to move up the list are 7% of the candidate's party result on the federal level, 10% on the state level and 14% on the electoral district level.[1] Candidates for sub-constituency level are listed on the ballot while voters need to write-in their preferred candidate on state and federal level.

Croatia

In Croatia, the voter can give his vote to a single candidate on the list, but only candidates who have received at least 10% of the party's votes take precedence over the other candidates on the list.[2]

Czech Republic

In the Czech Republic, voters are given 4 preference votes. Only candidates who have received more than 5% of preferential votes at the regional level take precedence over the list. [3]

Indonesia

In Indonesia, any candidate who has obtained at least 30% of the quota is automatically elected.[4]

Netherlands

In the Netherlands, the voter can give his vote to any candidate in a list (for example, in elections for the House of the Representatives); the vote for this candidate is called a "preference vote" (voorkeurstem in Dutch). If a candidate has at least 25% of the quota then he/she takes priority over the party's other candidates who stand higher on the party list but received fewer preference votes. Most people vote for the top candidate, to indicate no special preference for any individual candidate, but support for the party in general. Sometimes, however, people want to express their support for a particular person. Many women, for example, vote for the first woman on the list. If a candidate gathers enough preference votes, then they get a seat in parliament, even if their position on the list would leave them without a seat. In the 2003 elections Hilbrand Nawijn, the former minister of migration and integration was elected into parliament for the Pim Fortuyn List by preference votes even though he was the last candidate on the list.

Slovakia

In Slovakia, each voter may, in addition to the party, select one to four candidates from the ordered party list. Candidates who are selected by more than 3% of the party's voters are elected (in order of total number of votes) first and only then is the party ordering used. For European elections, voters select two candidates and the candidates must have more than 10% of the total votes to override the party list. In the European election in 2009 (the most recent election run under this system) three of Slovakia's thirteen MEPs were elected solely by virtue of preference votes (having party list positions too low to have won otherwise) and only one (Katarína Neveďalová of SMER) was elected solely by virtue of her position on the party list (having fewer preference votes than a number of other candidates who themselves, nevertheless had preferences from fewer than 10 percent of their party's voters).

Sweden

In Sweden, the 'most open' list is used, but a person needs to receive 5% of the party's votes for the personal vote to overrule the ordering on the party list.[5] Voting without expressing a preference between individuals is possible, although the parties urge their voters to support the party's prime candidate, to protect them from being beaten by someone ranked lower by the party.

Most open

The 'most open' list system is the one where the absolute number of votes every candidate receives fully determines the "order of election" (the list ranking only possibly serving as a 'tiebreaker').

When such a system is used, one could make the case that within every party an additional virtual single non-transferable vote (SNTV) election is taking place.

This system is used in all Finnish, Latvian, and Brazilian multiple-seat elections. While ties may be resolved by a coin toss in Finland, the oldest candidate wins the tie in Brazil. Since 2001, most open lists are also used for the 96 proportional seats in the 242-member upper house of Japan (the other 146 are elected through a majoritarian, SNTV/FPTP system).

Free or panachage

A 'free list', more usually called panachage, is similar in principle to the most open list, but instead of having just one vote for one candidate in one list, an elector has (usually) as many votes as there are seats to be filled, and may distribute these among different candidates in different lists. Electors may also give more votes to one candidate, in a manner similar to cumulative voting, and delete (German: Streichen or Reihen, French: latoisage) the names of some candidates. This gives the elector more control over which candidates are elected.[7]

It is used in elections at all levels in Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, and Switzerland, in congressional elections in Ecuador, El Salvador, and Honduras, as well as in local elections in a majority of German states and in French communes with under 1,000 inhabitants.

Practical operation

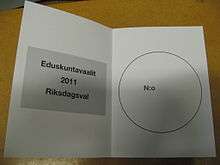

Some ways to operate an open list system when using traditional paper-based voting are as follows:

- One method (used in Belgium and Australia) is to have a large ballot paper with a box for each party and sub-boxes for the various candidates. In Belgium, where electronic voting is used in most voting precincts, the voter has to choose with an electronic pencil on a touchscreen between lists and blank vote, then on the list's page between the top box (vote for the list without preference for specific candidates) or the box(es) for one or several candidates on the same list.[8] The computer program forbids spoilt vote.

- Another method (used in Slovakia and Spain) is to have a separate ballot paper for each party. To maintain voter secrecy, the voter is handed ballot papers for every party. The voter chooses the candidates (or may vote for the party as a whole) on one of the ballot papers and puts that paper into an envelope, putting the envelope into the ballot box, and discarding the other ballot papers into a bin provided for that purpose.

- In Brazil, each candidate is assigned a number (in which the first 2 digits are the party number and the others the candidate's number within the party). The voting machine has a telephone-like panel where the voter presses the buttons for the number of their chosen candidate. In Finland, each candidate is assigned a 3-digit number.

- In Italy, the voter must write the name of each chosen candidate in blank boxes under the party box.

Countries with open list proportional representation

Some of these states may use other systems in addition to open list. For example, open list may decide only upper house legislative elections while another electoral system is used for lower house elections.

Africa

Europe

.svg.png)

Americas

Asia-Pacific

References

- ↑ Vorzugsstimmenvergabe bei einer Nationalratswahl ("Preferential voting in a federal election") HELP.gv.at

- ↑ "Zakon o izborima zastupnika u Hrvatski sabor (Act on Election of Representatives to the Croatian Parliament)" (in Croatian). Retrieved August 27, 2018.

- ↑ http://archive.ipu.org/parline-e/reports/2083_B.htm

- ↑ http://archive.ipu.org/parline-e/reports/2147_B.htm

- ↑ Swedish Election Authority: Elections in Sweden: The way its done Archived 2009-02-25 at the Wayback Machine. (page 16)

- ↑ Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications: Results of the 24th regular election of members of the House of Councillors: Proportional election, Japanese Communist Party results (lists preference votes by candidate and prefecture) (in Japanese)

- ↑ "Open, closed, and free lists", ACE Electoral Knowledge Network

- ↑ (in French) « Voilà comment voter électroniquement avec Smartmatic », video posted on Youtube by the Belgian Federal Interior Ministry

- ↑ http://archive.ipu.org/parline-e/reports/2375_B.htm

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Electoral Systems in Europe: An Overview". European Parliament in Brussels: European Centre for Parliamentary Research and Documentation. October 2000. Archived from the original on May 9, 2013. Retrieved July 6, 2012.

- ↑ "Izborni zakon BiH, članovi 9.5 i 9.8" (PDF). Retrieved September 2, 2012.

- ↑ "Zakon o izborima zastupnika u Hrvatski sabor (Act on Election of Representatives to the Croatian Parliament)" (in Croatian). Retrieved April 8, 2018.

- ↑ Miriam A. Golden, Lucio Picci (April 2008). "Pork-Barrel Politics in Postwar Italy, 1953-94" (PDF). American Journal of Political Science. 52 (2). doi:10.1111/j.1540-5907.2007.00312.x.

- ↑ http://www.electionguide.org/countries/id/125/

- 1 2 3 Mainwaring, Scott (October 1991). "Politicians, Parties, and Electoral Systems: Brazil in Comparative Perspective" (PDF). Comparative Politics. 24 (1): 21–43. doi:10.2307/422200.

- ↑ Craig Arceneaux, Democratic Latin America, Routledge, 2015 ISBN 9781317348825 p.339

- ↑ George Rodriguez, "Voters head to the polls in El Salvador to elect legislators, mayors", Tico Times, 28 February 2015

- ↑ (in Spanish) "Papeletas para las elecciones 2015 (reproduction of ballot papers and explanation of the new voting system)", Tribunal Supremo Electoral

- ↑ Matthew S. Shugart, "El Salvador joins the panachage ranks, president’s party holds steady", Fruits and Votes, 8 March 2015

- ↑ "Honduras", Election Passport

- ↑ http://archive.ipu.org/parline-e/reports/2245_B.htm

- ↑ http://www.electionguide.org/countries/id/170/

- ↑ "http://archive.ipu.org/parline-e/reports/2299_B.htm"

- ↑ Fijan elections office. "Electoral decree 2014" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 3 July 2014.

- ↑ Bruno, Greg (February 5, 2009). "Reshuffling the Political Deck". Backgrounder: Iraq's Political Landscape. Council on Foreign Relations. Retrieved July 8, 2012.

- ↑ ja:非拘束名簿式

- ↑ http://archive.ipu.org/parline-e/reports/2163_B.htm

- ↑ http://gulfnews.com/news/mena/lebanon/lebanon-to-hold-parliamentary-elections-in-may-2018-1.2043638. Retrieved 23 June 2017. Missing or empty

|title=(help)

- ↑ "Country Profile: Czech Republic".

- ↑ "Country Profile: Estonia". 2011-04-15. Retrieved June 30, 2012.

- ↑ "Country Profile: Latvia". 08/05/2011. Retrieved June 30, 2012. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ "Country Profile: Luxembourg". 02/04/2010. Retrieved 07/08/2012. Check date values in:

|accessdate=, |date=(help) - ↑ "Country Profile: Netherlands". 2010-10-14. Retrieved June 30, 2012.

- ↑ "Country Profile: Norway". 2011-03-18. Retrieved 07/08/2012. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help) - ↑ "Country Profile: Slovakia". 02/01/2012. Retrieved June 30, 2012. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ "Country Profile: Slovenia". 2012-02-28. Retrieved June 30, 2012.

- ↑ "Country Profile: Sweden". ElectionGuide. Consortium for Elections and Political Process Strengthening. 2010-08-08. Retrieved 07/08/2012. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help) - ↑ "Country Profile: Colombia". 2012-06-19. Retrieved 07/08/2012. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help) - ↑ "Country Profile: Indonesia". 2010-11-26. Retrieved June 30, 2012.

- ↑ "Country Profile: Sri Lanka". 2010-02-18. Retrieved June 30, 2012.

External links

- British Columbia Citizens' Assembly on Electoral Reform - A debate on the merits of open and closed lists by the Citizens' Assembly on Electoral Reform in the Canadian province of British Columbia, 2004.

- "Preferential Voting: Definition and Classification" - Paper presented by Jurij Toplak at the annual meeting of the Midwest Political Science Association's 67th Annual National Conference, Chicago, IL, April 2009.