Cudjoe Lewis

| Cudjo Kazoola (Kossola) Lewis | |

|---|---|

.jpg) Portrait of Cudjo Kazoola Lewis by Emma Langdon Roche, c. 1914 | |

| Born |

Oluale Kossola c. 1841[1] Banté region, West Africa[2] |

| Died |

July 17, 1935 (aged 94/95) Africatown, Mobile, Alabama |

| Occupation | farmer, laborer, church sexton |

| Known for | Last known survivor of the Atlantic slave trade between Africa and the United States. |

Cudjoe Kazoola Lewis (c. 1840 – July 17, 1935), or Cudjo Lewis or Oluale Kossola,[3] was the last known survivor of the Atlantic slave trade between Africa and the United States. Together with 115 other African captives, he was brought illegally to the United States on board the ship Clotilda in 1860.[4] They were landed in the backwaters near Mobile, Alabama, and hidden from authorities. The ship was scuttled to evade discovery.

After the Civil War, Lewis and other members of the Clotilda group became free and established a community at Magazine Point, north of Mobile, Alabama. Now designated as the Africatown Historic District, it was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2012.[5] In old age Lewis preserved the experiences of the Clotilda captives by providing accounts of the history of the group to visitors, including Mobile artist and author Emma Langdon Roche and author and folklorist Zora Neale Hurston.

Early life and enslavement

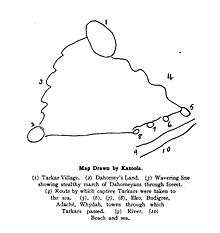

He was born as Kossola or Oluale Kossola (American listeners would later transcribe his given name as "Kazoola"), around 1840 in West Africa. Analyzing names and the other words attributed to the Africatown founders, historian Sylviane Diouf has concluded that he and many other members of the community belonged to what is now known as the Yoruba ethnic group, and lived in the Banté region of what is now Benin. His father was named Oluwale (or Oluale) and his mother Fondlolu; he had five full siblings and twelve half-siblings, the children of his father's other two wives.[6] Interviewers Roche and Hurston, and those who used their work, referred to Lewis and his fellow-captives as "Tarkars." Diouf believes that the term "Tarkar" might have come from a misunderstanding of the name of a local king, or the name of a town.[7]

During April or May 1860, Lewis was taken prisoner by the army of the Kingdom of Dahomey as part of its annual dry-season raids for slaves.[8][9] Along with other captives, he was taken to the slaving port of Ouidah and sold to Captain William Foster of the Clotilda, a ship based in Mobile, Alabama, and owned by businessman Timothy Meaher. Although importation of enslaved persons into the United States had been illegal since 1808, Meaher may have believed that he could flout the law without consequences.[10] Some reports suggest that breaking the law was part of Meaher's motivation for importing the slaves, as he reportedly bet a businessman $100,000 that he could circumvent the prohibition on transporting slaves.[11] In a similar situation, the owners of the Wanderer, which had illegally brought a cargo of enslaved people to Georgia in 1858, were indicted and tried for piracy in the federal court in Savannah in May 1860 but acquitted in a jury trial.[12] By the time the Clotilda reached the Mississippi coast in July 1860, government officials had been alerted to its activities, and Timothy Meaher, his brother Burns, and their associate John Dabney were charged with illegal possession of the captives. However, there was a gap of almost five months between the end of July 1860, when summonses and writs of seizure were issued against the Meahers and Dabney, and mid-December when they received them. During the intervening period the captives were dispersed and hidden, and without their physical presence as evidence the case was dismissed in January 1861.[13][14]

Until the end of the Civil War (1861–65), Lewis and his fellows lived as de facto slaves of Meaher, his brothers, or their associates.[15] Lewis was purchased by James Meaher, for whom he worked as a deckhand on a steamer.[16] During this time he became known as "Cudjo Lewis." He later explained that he suggested "Cudjo," a day-name commonly given to boys born on a Monday, as an alternative to his given name when James Meaher had difficulty pronouncing "Kossola." Historian Diouf posits that the surname "Lewis" was a corruption of his father's name Oluale, sharing the "lu" sound; in his homeland, the closest analogue to what Americans understood as a surname would have been a patronymic.[17]

Life in Africatown

Establishment of Africatown

During their time in slavery, Lewis and many of the other Clotilda captives were located at an area north of Mobile known as Magazine Point, the Plateau, or "Meaher's hammock," where the Meahers owned a mill and a shipyard. Although only three miles from the town of Mobile, it was isolated, separated from the city by a swamp and a forest, and easily accessible only by water. After the abolition of slavery and the end of the Civil War, the Clotilda captives tried to raise money to return to their homeland. The men worked in lumber mills and the women raised and sold produce, but these occupations did not allow them to acquire sufficient funds.[18] After realizing that they would not be able to return to Africa, the group deputized Lewis to ask Timothy Meaher for a grant of land. When he refused, the members of the community continued to raise money and began to purchase land around Magazine Point.[19] On September 30, 1872, Lewis bought about two acres of land in the Plateau area for $100.00.[20]

Africatown developed as a self-contained community. The group appointed leaders to enforce communal norms derived from their shared African background, and developed institutions including a church, a school, and a cemetery. Diouf explains that Africatown was unique because it was both a "black town," inhabited exclusively by people of African ancestry, and an enclave of people born in another country. She writes, "Black towns were safe havens from racism, but African Town was a refuge from Americans."[21] Writing in 1914, Emma Langdon Roche noted that the surviving founders of Africatown preferred to speak in their own language among themselves. She described the English of adults as "very broken and not always intelligible even to those who have lived among them for many years."[22] However, the residents also adopted some American customs, including Christianity. Lewis converted in 1869, joining a Baptist church.[23]

.jpg)

Marriage and family life

During the mid-1860s Lewis established a common-law relationship with another Clotilda survivor, Abile (Americanized as "Celia"). They formally married on March 15, 1880, along with several other couples from Africatown. They remained together until Abile's death in 1905.[24]

They had six children, five sons and a daughter, to each of whom they gave both an African name and an American name.[11] Their eldest son, Aleck (or Elick) Iyadjemi, became a grocer; he brought his wife to live in a house on his father's land. Diouf describes this arrangement as a Yoruba-style "family compound." Another son, Cudjoe Feïchtan, was fatally shot by a sheriff's deputy in 1902.[11] Lewis outlived all of his children as well as his wife. He allowed his daughter-in-law Mary Wood Lewis, his grandchildren, and eventually her second husband Joe Lewis (no relation) to remain in their house in the compound.[25]

Lewis worked as a farmer and laborer until 1902, when his buggy was damaged and he was injured in a collision with a train in Mobile. As he was then unable to work, the community appointed him as sexton of the church. In 1903 it took the name of the Union Missionary Baptist Church.[26]

Participation in American institutions

Although native-born American former slaves became citizens upon the passage of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution in July 1868, this change in status did not apply to the members of the Clotilda group, who were foreign-born. Cudjo Kazoola Lewis became a naturalized American citizen on October 24, 1868.[27]

Lewis utilized the American legal system in 1902 after his injury in the buggy-train collision. After the Louisville and Nashville Railroad refused to pay damages, he hired an attorney, sued the railroad, and won a significant settlement of $650.00. The award was overturned on appeal.[28]

Role as storyteller and historian

In the first quarter of the 20th century, Lewis began to serve as an informant for scholars and other writers, sharing the history of the Clotilda Africans and traditional stories and tales. Emma Langdon Roche, a Mobile-based writer and artist, interviewed Lewis and the other survivors for her 1914 book Historic Sketches of the South. She described their capture in Africa, enslavement, and lives in Africatown. They requested that she use their African names in her work, in the hope that it might reach their homeland "where some might remember them."[29]

By 1925, Lewis was the last African survivor of the Clotilda; he was interviewed by educator and folklorist Arthur Huff Fauset of Philadelphia. In 1927 Fauset published two of Lewis' animal tales, "T'appin's magic dipper and whip" and "T'appin fooled by Billy Goat's eyes," and "Lion Hunt," his autobiographical account about hunting in Africa, in the Journal of American Folklore.[30]

In 1927 Lewis was interviewed by the folklorist Zora Neale Hurston. The next year she published an article, "Cudjoe's Own Story of the Last African Slaver" (1928). According to her biographer Robert E. Hemenway, this piece largely plagiarized Emma Roche's work,[31] although Hurston added information about daily life in Lewis' home village of Banté.[32] In 1928 Hurston returned with additional resources; she conducted more interviews, took photographs, and recorded what is the only known film footage of an African who had been trafficked to the United States through the slave trade. Based on this material, she wrote a manuscript, Barracoon, which Hemenway described as "a highly dramatic, semifictionalized narrative intended for the popular reader."[33][34] After this round of interviews, Hurston's literary patron, philanthropist Charlotte Osgood Mason, learned of Lewis and began to send him money for his support.[35] Lewis was also interviewed by journalists for local and national publications.[36] Hurston's book Barracoon: The Story of the Last Black Cargo was finally published on May 8, 2018.[37]

Legacy

Cudjo Lewis died July 17, 1935, and was buried at the Plateau Cemetery in Africatown. Since his death, his status as the last survivor of the Clotilda and the written record created by his interviewers have made him a public figure of the history of the community.

- In 1959 a memorial bust of Lewis was erected in front of Africatown's Union Missionary Baptist Church atop a pyramid of bricks made by the Clotilda captives. It was made on behalf of the Progressive League of Africatown.[38][39]

- In 1977 the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History (now the Association for the Study of African American Life and History) commemorated Lewis and the Clotilda group.[40]

- Around 1990 the City of Mobile and Mobile alumnae chapter of Delta Sigma Theta sorority erected a commemorative marker for Lewis in the Plateau Cemetery.[41]

- In 2007 two African filmmakers donated a bust of Lewis to the Africatown Welcome Center. It was severely damaged by vandalism in 2011.[42][43]

- In 2010, archaeologists from the College of William and Mary excavated Lewis' homesite in Africatown, along with those of two other residents, to search for artifacts and evidence of African practices in the founders' daily lives in the United States.[44]

- Barracoon: The Story of the Last Black Cargo, Zora Neale Hurston's account of Lewis' life, was published for the first time in 2018.[45]

See also

References

- ↑ Diouf, Sylviane A. "Cudjo Lewis". Encyclopedia of Alabama. Retrieved 5/12/18. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help) - ↑ Diouf, Sylviane A. 2007. Dreams of Africa in Alabama: The Slave Ship Clotilda and the Story of the Last Africans Brought to America. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 40.

- ↑ Diouf, Sylviane A. (20 October 2009). "Cudjo Lewis". Encyclopedia of Alabama. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- ↑ Roche, Emma Langdon (1914). Historic Sketches of the South. New York: Knickerbocker Press. p. 120.

- ↑ Teague, Matthew (June 6, 2015). "American slaves' origins live on in Alabama's Africatown". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved May 27, 2016.

- ↑ Diouf, Dreams of Africa, pp. 40-43.

- ↑ Diouf, Dreams of Africa, p. 41.

- ↑ Diuof, Dreams of Africa, p. 46

- ↑ Barnes, Sandra T., ed. (1997). Africa's Ogun: Old World and New (2nd ed.). Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. pp. 47–48. ISBN 978-0253210838.

- ↑ Pilgrim, David (June 2005). "Question of the Month: Cudjo Lewis: Last Slave in the US?". Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia. Ferris State University. Retrieved May 27, 2016.

- 1 2 3 "Story of the last survivor of the last slave ship to travel from Africa to US is published after 87 years". The Independent. 2018-05-04. Retrieved 2018-05-21.

- ↑ Rohrer, Katherine E. (June 18, 2010). "Wanderer". New Georgia Encyclopedia. Georgia Humanities Council & University of Georgia Press. Retrieved August 9, 2016.

- ↑ "The Clotilda: A Finding Aid" (PDF). National Archives at Atlanta. Retrieved May 29, 2016.

- ↑ "AfricaTown USA". Local Legacies: Celebrating Community Roots. Library of Congress American Folklife Center. 2000. Retrieved May 27, 2016.

- ↑ Diouf. Dreams of Africa, chapter 4.

- ↑ Diouf, Dreams of Africa, pp. 86, 93.

- ↑ Diouf, Dreams of Africa, pp. 92, 134.

- ↑ Roche, Historic Sketches, pp. 114-115.

- ↑ Roche, Historic Sketches, pp. 116-117.

- ↑ Diouf, Dreams of Africa, p. 155.

- ↑ Diouf, Dreams of Africa, pp. 157, 184.

- ↑ Roche, Historic Sketches, pp. 125-126.

- ↑ Diouf, Dreams of Africa, p. 169.

- ↑ Diouf, Dreams of Africa, pp. 136, 180, 217.

- ↑ Diouf, Dreams of Africa, pp. 217-219.

- ↑ Diouf, Dreams of Africa, p. 214.

- ↑ Diouf, Dreams of Africa, p. 165.

- ↑ Diouf, Dreams of Africa, pp. 211-214.

- ↑ Roche, Historic Sketches, pp. 120-121.

- ↑ Fauset, Arthur Huff (July–September 1927). "Negro Folk Tales from the South (Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana)". Journal of American Folklore. 40: 213–303.

- ↑ Hemenway, Robert E. (1980). Zora Neale Hurston: A Literary Biography. Urbana and Chicago, IL: University of Illinois Press. pp. 96–99. ISBN 978-0252008078.

- ↑ Hurston, Zora Neale (October 1927). "Cudjoe's Own Story of the Last African Slaver". Journal of Negro History. 12: 648–663.

- ↑ Hemenway, Zora Neale Hurston, pp. 100-101.

- ↑ Diouf, Dreams of Africa, p. 225.

- ↑ Diouf, Dreams of Africa, p. 225.

- ↑ Diouf, Dreams of Africa, p. 226.

- ↑ Little, Becky. "The Last Slave Ship Survivor Gave an Interview in the 1930s. It Just Surfaced". History. History. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- ↑ "Bust of Last Survivor of Slave Ship "Clotilde" stolen in Mobile". Gadsden Times. January 8, 2002. Retrieved May 27, 2016.

- ↑ Lautier, Lewis (September 12, 1959). "Capital Spotlight". The Afro-American. Retrieved May 27, 2016.

- ↑ "Escaped slaves formed "African town" near Mobile". Tuscaloosa News. October 2, 1977. Retrieved May 27, 2016.

- ↑ "Plateau Historic Graveyard". Dora Franklin Finley African American Heritage Trail. Retrieved May 27, 2016.

- ↑ Pickett, Rhoda A. (March 23, 2011). "Busts of Cudjoe Lewis, John Smith vandalized at Africatown Welcome Center". The Press-Register. Retrieved May 27, 2016.

- ↑ Diouf, Dreams of Africa, p. 232.

- ↑ Hoffman, Roy (August 9, 2010). "Dig reveals story of America's last slave ship -- and its survivors". The Press-Register. Retrieved May 27, 2016.

- ↑ "The Last Slave (with excerpt from Barracoon)". New York Magazine. 2018. pp. 32–39.

External links

- Emma Langdon Roche, Historic Sketches of the South, Internet Archive.

- Cudjoe Lewis at Find a Grave

- Zora Neale Hurston, 1928 film footage (first 40 seconds may depict Cudjo Kossola Lewis), YouTube.

- Sylviane A. Diouf, "Cudjo Lewis", Encyclopedia of Alabama.