Oiran

Oiran (花魁) were courtesans in Japan.[1] The oiran were considered a type of yūjo (遊女) "woman of pleasure" or prostitute. However, they are distinguished from ordinary yūjo in that they were entertainers, and many became celebrities even outside the pleasure districts. Their art and fashions often set trends and, because of this, cultural aspects of oiran traditions continue to be preserved to this day.[2][3]

Etymology

The word oiran comes from the Japanese phrase oira no tokoro no nēsan (おいらの所の姉さん) which translates into "my elder sister." When written in kanji, the word consists of two characters, 花 meaning "flower", and 魁 meaning "leader" or "first." Technically, only the high-class prostitutes of Yoshiwara were called oiran, although the term is widely applied to all.[4]

History

Rise to prominence

Courtesan culture arose in the early Edo period (1600–1868). At this time, laws were passed restricting brothels to pleasure quarters (yūkaku (遊廓、遊郭)), which were walled districts set some distance from the city center. Although there were many such quarters, the three with the most lasting prominence were the Shimabara in Kyoto, the Shinmachi in Osaka, and in Edo (present-day Tokyo), the Yoshiwara. These rapidly grew into large, self-contained neighborhoods offering all manner of entertainment, including fine dining, free performances, and frequent festivals and parades.

Status and rank

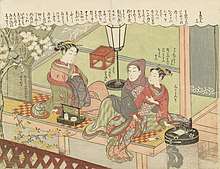

Compared to yūjo (prostitutes), whose primary attraction was their sexual favors, courtesans were first and foremost entertainers. In order to become an oiran, a woman had to be educated in a range of skills, including the traditional arts of sadō (Japanese tea ceremony), ikebana (flower arranging), and calligraphy. Oiran also learned to play the koto, shakuhachi, tsuzumi (hand drum), and shamisen.[5] Clients also expected them to be well-read and able to converse and write with wit and elegance.[6]

Within the pleasure quarters, courtesans' prestige was based on their beauty, character, education, and artistic ability, rather than their birth.[7]

The highest rank of courtesan was the tayū (太夫), followed by the kōshi (格子).[8][9] Unlike a common prostitute, the tayū had sufficient prestige to refuse clients.[10] Her high status also made a tayū extremely pricey—a tayū's fee for one evening was between one ryo and one ryo three bu, well beyond a laborer's monthly wage and comparable to a shop assistant's annual salary.[11]

In 1761, the last tayū of the Yoshiwara retired, marking the end of the tayū and kōshi ranks in that pleasure quarter. The word "oiran" therefore appeared in the Yoshiwara as a polite term of address for any remaining woman of courtesan rank.[12]

Decline

The isolation within the closed districts resulted in the oiran becoming highly ritualised in many ways and increasingly removed from the changing society. Strict etiquette governed appropriate behavior. Their speech preserved the formal court standards rather than the common language. Casual visitors were rejected; clients were accepted only by referral from certain teahouses, and only by appointment, which increased both the cost and the delay. In a time when both dress and hairstyles were becoming simpler, oiran's costumes became more and more ornate, culminating in a style with eight or more pins and combs in the hair, and many layers of highly ornamented garments derived from the early Edo period. Similarly, the entertainments offered were derived from those of the original courtesans generations before.[12] Ultimately, the culture of the oiran grew increasingly rarefied and remote from everyday life, and their clients dwindled.

The rise of the geisha ended the era of the oiran. Geisha were originally entertainers who provided a suitable backdrop for the courtesans, and their restrained dress and hairstyles were intended to prevent them from competing with courtesans. However, their sartorial restraint translated into chic, and their relative lack of formality into approachability. The types of entertainment they offered were more to the average person's taste. Most importantly, they were much less expensive than the courtesans. By the late 19th century, geisha had replaced oiran as the companion of choice for wealthy Japanese men.

Oiran continued to see clients in the old pleasure quarters, but they were no longer at the cutting edge of fashion. During World War II, when any show of luxury was frowned upon, courtesan culture suffered. The anti-prostitution laws of 1958 dealt it the final blow.

Modern Oiran

Tayū continue to entertain as geisha do, but no longer provide sex. However, there are fewer than five tayū, in comparison to the three hundred geisha in Kyoto today. The last remaining tayū house is located in Shimabara, which lost its official status as a hanamachi in the late 20th century because of the tayūs' decline.[13] However, some still recognize Shimabara as a "flower town," since geisha and tayū still work there and the activity of the tayū is slowly growing. The few remaining women still currently practicing the arts of the tayū (without the sexual aspect) do so as a preservation of cultural heritage rather than as a profession or lifestyle.[14]

Courtesan parade

The Bunsui Sakura Matsuri Oiran Dōchū is an annual event held every April in Bunsui, Niigata (now part of the city of Tsubame). The parade, which takes place under the Spring cherry blossoms, historically re-enacts the walk made by top courtesans around their district in honour of their guests. The modern parade features three oiran in full traditional attire with approximately 70 accompanying servants. The oiran, who are named Shinano, Sakura, and Bunsui, have a slow distinctive gait because they wear 15 cm (5.9 in) high wooden sandals. Due to the event's popularity in Japan, organisers are inundated with applications to be one of the three oiran or a servant. Dōchū is a shortened form of oiran-dochu, it is also known as the Dream Parade of Echigo (Echigo no yume-dochu).

The Ōsu Street Performers' Festival is an event held around Ōsu Kannon Temple in Nagoya yearly around the beginning of October. The highlight of this two-day festival is the slow procession of oiran through the Ōsu Kannon shopping arcade. Thousands of spectators crowd the shopping streets on these days to get close enough to photograph the oiran and their retinue of male bodyguards and entourage of apprentices (young women in distinctive red kimono, white face paint and loose, long black hair reminiscent of Shinto priestesses).

An Oiran Dōchū parade is held in the Minamishinagawa district near Aomono-Yokochō, Shinagawa every September.[15]

See also

References

- ↑ "Oiran". The Kyoto Project. Retrieved 30 March 2018.

- ↑ ShinoStore (2015-02-22), OIRAN 花魁 - Japanese Lamp (020L), retrieved 2018-08-13

- ↑ ktodoma (2016-11-20), Oiran 花魁 in New York, retrieved 2018-08-13

- ↑ 2006-1-27, 藤田 真一, 京都・角屋の文化 ―学問の手伝えること― Archived 2011-03-21 at the Wayback Machine., Kansai University. Quote: 「花魁は、江戸の吉原にしかいません。吉原にも当初は太夫がいたのですが、揚屋が消滅したのにともなって、太夫もいなくなりました。その替わりに出てきたのが、花魁なのです。ですから、花魁は江戸吉原専用の語なのです。」

- ↑ Seigle 1993, pp. 123, 202.

- ↑ Hickey 1998, p. 28.

- ↑ Hickey 1998, pp. 26-27.

- ↑ Early Modern Japanese Literature: An Anthology, 1600-1900. Columbia University Press, 2008.

- ↑ The life of an amorous woman. Taylor & Francis. Commentary "APPENDIX III. THE HIERARCHY OF COURTESANS" p. 286.

- ↑ Seigle 1993, p. 87.

- ↑ Ryū 2008, p. 69.

- 1 2 Swinton 1995, p. 37.

- ↑ Dalby, Liza. "Courtesans and Geisha – the Tayû". www.lizadalby.com Retrieved 3-11-2014.

- ↑ Dalby 1995, p. 64.

- ↑ Miura, Yoshiaki (30 November 2014). "Shinagawa, a gateway to old and new Tokyo". The Japan Times Online. Retrieved 23 September 2018.

Further reading

- Swinton, Elizabeth de Sabato; Campbell, Kazue Edamatsu; Dalby, Liza Crihfield; Oshima, Mark (1995). The women of the pleasure quarter: Japanese paintings and prints of the floating world. Hudson Hills Press. ISBN 9781555951153.

- Dalby, Liza Crihfield. Chapter: Courtesan and Geisha: The Real Women of the Pleasure Quarter.

- Swinton, Elizabeth de Sabato. Chapter: Reflections on the Floating World.

- Becker, J. E. de (2000). The Nightless City: Or, The History of the Yoshiwara Yūkwaku. ICG Muse. ISBN 9784925080316.

- Hickey, Gary (1998). Beauty & Desire in Edo Period Japan. National Gallery of Australia. ISBN 9780642130846.

- Longstreet, Stephen; Longstreet, Ethel (1988). Yoshiwara: The Pleasure Quarters of Old Tokyo. C.E. Tuttle Company. ISBN 9780804815994.

- Ryū, Keiichirō (2008). The Blade of the Courtesans. Vertical. ISBN 9781934287019.

- Seigle, Cecilia Segawa (1993). Yoshiwara: The Glittering World of the Japanese Courtesan. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 9780824814885.

External links

| Look up 花魁 or oiran in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Oiran. |