Odissi

Odissi (Odia: ଓଡ଼ିଶୀ Oḍiśī), also referred to as Orissi in older literature, is a major ancient Indian classical dance that originated in the Hindu temples of Odisha – an eastern coastal state of India.[1][2][3] Odissi, in its history, was performed predominantly by women,[1][4] and expressed religious stories and spiritual ideas, particularly of Vaishnavism (Vishnu as Jagannath). Odissi performances have also expressed ideas of other traditions such as those related to Hindu gods Shiva and Surya, as well as Hindu goddesses (Shaktism).[5]

| This article is part of a series on |

| Odisha |

|---|

|

| Governance |

|

| Topics |

| GI Products |

|

Districts Divisions |

|

|

.jpg)

The theoretical foundations of Odissi trace to the ancient Sanskrit text Natya Shastra, its existence in antiquity evidenced by the dance poses in the sculptures of Odissi Hindu temples,[1][7] and archeological sites related to Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism.[8][9] The Odissi dance tradition declined during the Islamic rule era,[10] and was suppressed under the British Rule.[11][12] The suppression was protested by the Indians, followed by its revival, reconstruction and expansion since India gained independence from the colonial rule.[9]

Odissi is traditionally a dance-drama genre of performance art, where the artist(s) and musicians play out a mythical story, a spiritual message or devotional poem from the Hindu texts, using symbolic costumes,[13] body movement, abhinaya (expressions) and mudras (gestures and sign language) set out in ancient Sanskrit literature.[14] Odissi is learnt and performed as a composite of basic dance motif called the Bhangas (symmetric body bends, stance). It involves lower (footwork), mid (torso) and upper (hand and head) as three sources of perfecting expression and audience engagement with geometric symmetry and rhythmic musical resonance.[15][16] An Odissi performance repertoire includes invocation, nritta (pure dance), nritya (expressive dance), natya (dance drama) and moksha (dance climax connoting freedom of the soul and spiritual release).[6][17]

Traditional Odissi exists in two major styles, the first perfected by women and focussed on solemn, spiritual temple dance (maharis); the second perfected by boys dressed as girls (gotipuas[18]) which diversified to include athletic and acrobatic moves, and were performed from festive occasions in temples to general folksy entertainment.[7] Modern Odissi productions by Indian artists have presented a diverse range of experimental ideas, culture fusion, themes and plays.[19]

History

The foundations of Odissi are found in Natya Shastra, the ancient Hindu Sanskrit text of performance arts.[20][21] The basic dance units described in Natyashastra, all 108 of them, are identical to those in Odissi.[21]

Natya Shastra is attributed to the ancient scholar Bharata Muni, and its first complete compilation is dated to between 200 BCE and 200 CE,[22][23] but estimates vary between 500 BCE and 500 CE.[24] The most studied version of the Natya Shastra text consists of about 6000 verses structured into 36 chapters.[22][25] The text, states Natalia Lidova, describes the theory of Tāṇḍava dance (Shiva), the theory of rasa, of bhāva, expression, gestures, acting techniques, basic steps, standing postures – all of which are part of Indian classical dances.[22][26] Dance and performance arts, states this ancient text,[27] are a form of expression of spiritual ideas, virtues and the essence of scriptures.[28] The Natya Shastra refers to four vrittis (methods of expressive delivery) in vogue – Avanti, Dakshinatya, Panchali and Odra-Magadhi; of these, the Odra refers to Odisha.[29]

More direct historical evidence of dance and music as an ancient performance art are found in archaeological sites such as caves and in temple carvings of Bhubaneswar, Konarak and Puri.[21][30] The Manchapuri cave in Udayagiri shows carvings of dance and musicians, and this has been dated to the time of Jain king Kharavela in the first or second century BCE. The Hathigumpha inscriptions, also dated to the same ruler, mention music and dance:[29][31]

(he [the king]) versed in the science of the Gandharvas (i.e., music), entertains the capital with the exhibition of dapa, dancing, singing and instrumental music and by causing to be held festivities and assemblies (samajas)...

— Hathigumpha inscription, Line 5, ~ 2nd-1st century BCE[32][33]

The musical tradition of Odisha also has ancient roots. Archeologists have reported the discovery of 20-key, carefully shaped polished basalt lithophone in Sankarjang, the highlands of Odisha, which is dated to about 1000 BCE.[34][35]

Medieval era

The Buddhist, Jain and Hindu archaeological sites in Odisha state, particularly the Assia range of hills show inscriptions and carvings of dances that are dated to the 6th to 9th century CE. Important sites include the Ranigumpha in Udaygiri, and various caves and temples at Lalitgiri, Ratnagiri and Alatgiri sites. The Buddhist icons, for example, are depicted as dancing gods and goddesses, with Haruka, Vajravarahi, and Marichi in Odissi-like postures.[36][37] Historical evidence, states Alexandra Carter, shows that Odissi Maharis (Hindu temple dancers) and dance halls architecture (nata-mandap) were in vogue at least by the 9th century CE.[38]

According to Kapila Vatsyayan, the Kalpasutra of Jainism, in its manuscripts discovered in Gujarat, includes classical Indian dance poses – such as the Samapada, the Tribhangi and the Chuaka of Odissi. This, states Vatsyayan, suggests that Odissi was admired or at least well known in distant parts of India, far from Odisha in the medieval era, to be included in the margins of an important Jain text.[39] However, the Jain manuscripts use the dance poses as decorative art in the margins and cover, but do not describe or discuss the dance. Hindu dance texts such as the Abhinaya Chandrika and Abhinaya Darpana provide a detailed description of the movements of the feet, hands, the standing postures, the movement and the dance repertoire.[40] It includes illustrations of the Karanãs mentioned in NãtyaShãstra.[41] Similarly, the illustrated Hindu text on temple architecture from Odisha, the Shilpaprakãsha, deals with Odia architecture and sculpture, and includes Odissi postures.[42]

Actual sculptures that have survived into the modern era and panel reliefs in Odia temples, dated to be from the 10th to 14th century, show Odissi dance. This is evidenced in Jagannath temple in Puri, as well as other temples of Vaishnavism, Shaivism, Shaktism and Vedic deities such as Surya (Sun) in Odisha.[5] There are several sculptures of dancers and musicians in Konark Sun Temple and Brahmeswara Temple in Bhubaneswar.[1][7]

The composition of the poetic texts by 8th century Shankaracharya and particularly of divine love inspired Gitagovinda by 12th century Jayadeva influenced the focus and growth of modern Odissi.[43] Odissi was performed in the temples by the dancers called Maharis, who played out these spiritual poems and underlying religious plays, after training and perfecting their art of dance starting from an early age, and who were revered as auspicious to religious services.[5][43]

Mughal and British rule period

After 12th-century, Odia temples, monasteries and nearby institutions such as the Puspagiri in eastern Indian subcontinent came under waves of attacks and ransacking by Muslim armies, a turmoil that impacted all arts and eroded the freedoms previously enjoyed by performance artists.[12] The official records of Sultan Firuz Shah Tughlaq's invasion in Odisha (1360-1361 CE), for example, describe the destruction of the Jagannath temple as well as numerous other temples, defacing of dancing statues, and ruining of dance halls.[44] This led to a broad decline in Odissi and other religious arts, but there were some benevolent rulers in this period who supported arts particularly through performances at courts.[12] During the Sultanate and Mughal era of India, the temple dancers were moved to entertain the Sultan's family and courts.[45] They became associated with concubinage to the nobility.

The Odissi dance likely expanded in the 17th century, states Alexandra Carter, under King Ramachandradeva's patronage.[46] This expansion integrated martial arts (akhanda) and athletics into Odissi dance, by engaging boys and youth called Gotipuas, as a means to physically train the young for the military and to resist foreign invasions.[46] According to Ragini Devi, historical evidence suggests that the Gotipuas tradition was known and nurtured in the 14th century, by Raja of Khurda.[47]

During the British Raj, the officials of the colonial government ridiculed the temple traditions, while Christian missionaries launched a sustained attack on the moral outrage of sensuousness of Odissi and other Hindu temple dance arts.[12][48][49] In 1872, a British civil servant named William Hunter watched a performance at the Jagannath temple in Puri, then wrote, "Indecent ceremonies disgraced the ritual, and dancing girls with rolling eyes put the modest worshipper to the blush...", and then attacked them as idol-worshipping prostitutes who expressed their devotion with "airy gyrations".[50]

Christian missionaries launched the "anti-dance movement" in 1892, to ban all such dance forms.[48] The dancers were dehumanized and stigmatized as prostitutes during the British period.[51][52] In 1910, the British colonial government in India banned temple dancing,[53] and the dance artists were reduced to abject poverty from the lack of any financial support for performance arts, combined with stereotyping stigma.[46]

Post-independence

The temple dance ban and the cultural discrimination during the colonial rule marshaled a movement by Hindus to question the stereotypes and to revive the regional arts of India, including Odissi.[48][49][50] Due to these efforts, the classical Indian dances witnessed a period of renaissance and reconstruction, which gained momentum particularly after Indians gained their freedom from colonialism.[54]

Odissi, along with several other major Indian dances gained recognition after efforts by many scholars and performers in the 1950s, particularly by Kavichandra Kalicharan Pattanayak, an Oriya poet, dramatist and researcher. Pattanayak is also credited with naming the dance form as "Odissi".[12][55]

Repertoire

.jpg)

Odissi, in the classical and medieval period has been, a team dance founded on Hindu texts.[7] This drama-dance involved women (Maharis) enacting a spiritual poem or a religious story either in the inner sanctum of a Hindu temple, or in the Natamandira attached to the temple.[56] The Odissi performing Maharis combined pure dance with expression, to play out and communicate the underlying text through abhinaya (gestures).[56][57] The performance art evolved to include another aspect, wherein teams of boys – dressed as girls – called Gotipuas expanded the Odissi repertoire, such as by adding acrobatics and athletic moves, and they performed both near the temples and open fairs for general folksy entertainment.[7][46] In the Indian tradition, many of the accomplished gotipuas became the gurus (teachers) in their adulthood.[46] Modern Odissi is a diversified performance art, men have joined the women, and its reconstruction since the 1950s have added new plays and aspects of other Indian dances.

Love is a universal theme and one of the paradigmatic values in Indian religions. This theme is expressed through sensuous love poems and metaphors of sexual union in Krishna-related literature, and as longing eros (Shringara) in its dance arts such as in Odissi, from the early times.[46][58] Hinduism, states Judith Hanna, encourages the artist to "strive to suggest, reveal or re-create the infinite, divine self", and art is considered as "the supreme means of realizing the Universal Being".[59] Physical intimacy is not something considered as a reason for shame, rather considered a form of celebration and worship, where the saint is the lover and the lover is the saint.[60] This aspect of Odissi dancing has been subdued in the modern post-colonial reconstructions, states Alexandra Carter, and the emphasis has expanded to "expressions of personal artistic excellence as ritualized spiritual articulations".[46]

The traditional Odissi repertoire, like all classical Indian dances, includes Nritta (pure dance, solo), Nritya (dance with emotions, solo) and Natya (dramatic dance, group).[61][62] These three performance aspects of Odissi are described and illustrated in the foundational Hindu texts, particularly the Natya Shastra, Abhinaya Darpana and the 16th-century Abhinaya Chandrika by Maheshwar Mahapatra of Odisha.[61][62]

- The Nritta performance is abstract, fast and rhythmic aspect of the dance.[63][62] The viewer is presented with pure movement in Nritta, wherein the emphasis is the beauty in motion, form, speed, range and pattern. This part of the repertoire has no interpretative aspect, no telling of story. It is a technical performance, and aims to engage the senses (prakriti) of the audience.[64]

- The Nritya is slower and expressive aspect of the dance that attempts to communicate feelings, storyline particularly with spiritual themes in Hindu dance traditions.[63][62] In a nritya, the dance-acting expands to include silent expression of words through the sign language of gestures and body motion set to musical notes. This part of a repertoire is more than sensory enjoyment, it aims to engage the emotions and mind of the viewer.[64]

- The Natyam is a play, typically a team performance, but can be acted out by a solo performer where the dancer uses certain standardized body movements to indicate a new character in the underlying story. A Natya incorporates the elements of a Nritya.[61][62]

- The Mokshya is a climatic pure dance of Odissi, aiming to highlight the liberation of soul and serenity in the spiritual.[17]

Odissi dance can be accompanied by both northern Indian (Hindustani) and southern Indian (Carnatic) music, though mainly, recitals are in Odia and Sanskrit language in the Odissi Music tradition.[61]

Sequence

Traditional Odissi repertoire sequence starts with an invocation called Mangalacharana.[6] A shloka (hymn) in praise of a God or Goddess is sung, such as to Jagannath (an avatar of Vishnu), the meaning of which is expressed through dance.[6] Mangalacharan is followed by Pushpanjali (offering of flowers) and Bhumi Pranam (salutation to mother earth).[6] The invocation also includes Trikhandi Pranam or the three-fold salutation – to the Devas (gods), to the Gurus (teachers) and to the Lokas or Rasikas (fellow dancers and audience).[65]

The next sequential step in an Odissi performance is Batu, also known as Battu Nrutya or Sthayee Nrutya or Batuka Bhairava.[6][66] It is a fast pace, pure dance (nritta) performed in the honor of Shiva. There is no song or recitation accompanying this part of the dance, just rhythmic music. This pure dance sequence in Odissi builds up to a Pallavi which is often slow, graceful & lyrical movements of the eyes, neck, torso & feet & slowly builds in a crescendo to climax in a fast tempo at the end.[6][66]

The nritya follows next, and consists of Abhinaya, or an expressional dance which is an enactment of a song or poetry.[6][66] The dancer(s) communicate the story in a sign language, using mudras (hand gestures), bhavas (enacting mood, emotions), eye and body movement.[67] The dance is fluid, graceful and sensual. Abhinaya in Odissi is performed to verses recited in Sanskrit or Odia language.[68] Most common are Abhinayas on Oriya songs or Sanskrit Ashthapadis or Sanskrit stutis like Dasavatar Stotram (depicting the ten incarnations of Lord Vishnu) or Ardhanari Stotram (half man, half woman form of the divine). Many regionally performed Abhinaya compositions are based on the Radha-Krishna theme.[43] The Astapadis of the Radha-Krishna love poem Gita Govinda written by Jayadeva are usually performed in Odisha, as part of the dance repertoire.[6][69]

The natya part, or dance drama, is next in sequence. Usually Hindu mythologies, epics and legendary dramas are chosen as themes.[70]

A distinctive part of the Odissi tradition is the inclusion of Moksha (or Mokshya[17]) finale in the performance sequence. This the concluding item of a recital.[6] Moksha in Hindu traditions means “spiritual liberation”. This dance movement traditionally attempts to convey a sense of spiritual release and soul liberation, soaring into the realm of pure aesthetics.[17] Movement and pose merge in a fast pace pure dance climax.[6]

Basic moves and mudras

The basic unit of Odissi are called bhangas. These are made up of eight belis, or body positions and movements, combined in many varieties.[41] Motion is uthas (rising or up), baithas (sitting or down) or sthankas (standing).[41] The gaits or movement on the dance floor is called chaalis, with movement tempo linked to emotions according to the classical Sanskrit texts. Thus, for example, burhas or quick pace suggest excitement, while a slow confused pace suggests dejection. For aesthetics, movement is centered on a core, a point in space or floor, and each dancer has her imaginary square of space, with spins and expression held within it.[41] The foot movement or pada bhedas too have basic dance units, and Odissi has six of these, in contrast to four found in most classical Indian dances.[41]

The three primary dance positions in Odissi are:[6]

- Samabhanga – the square position, with weight equally placed on the two legs, spine straight, arms raised up with elbows bent.

- Abhanga – the body weight shifts from side to side, due to deep leg bends, while the feet and knees are turned outwards, and one hip extending sideways.

- Tribhanga – is an S-shaped three-fold bending of body, with torso deflecting in one direction while the head and hips deflecting in the opposite direction of torso. Further, the hands and legs frame the body into a composite of two squares (rectangle), providing an aesthetic frame of reference. This is described in the ancient Sanskrit texts, and forms of it are found in other Hindu dance arts, but tribhanga postures developed most in and are distinctive to Odissi, and they are found in historic Hindu temple reliefs.[6]

Mudras or Hastas are hand gestures which are used to express the meaning of a given act.[71] Like all classical dances of India, the aim of Odissi is in part to convey emotions, mood and inner feelings in the story by appropriate hand and facial gestures. There are 63 Hastas in modern Odissi dance, and these have the same names or structure as those in the pan-Indian Hindu texts, but most closely matching those in the Abhinaya Chandrika.[41][71] These are subdivided into three, according to the traditional texts:[71]

- Asamyukta Hasta – Single hand Mudras – 28 Prakar (gestures, for instance to communicate a salute, prayer, embrace, energy, bond, swing, carriage, shell, arrow, holding a thing, wheel, and so on.)

- Samyukta Hasta – Double hand Mudras – 24 Prakar (gestures, for instance to indicate a flag, flower, type of bird or animal, moon, action like grasping, and so on.)

- Nrutya Hasta – “Pure Dance” Mudras

The Mudra system is derived from the "Abhinaya Darpana" by Nandikeshavara and the ancient Natya Shastra of Bharata Muni.[71]

Costumes

The Odissi dancers are colorfully dressed with makeup and jewellery. The Saree worn by Odissi dancers are brightly coloured, and usually of local silk (Pattasari).[72] It is worn with pleats, or may have a pleat tailor stitched in front, to allow maximum flexibility during the footwork.[73] These sarees have traditional prints of Odisha with regional designs and embellishments, and may be the Sambalpuri Saree and Bomkai Saree.

The jewellery includes silver pieces, a metal favored in regional tradition.[74] The hair is tied up, and typically drawn into an elaborate bun resembling a Hindu temple spire, and decorated with Seenthi.[73][75] Their hairstyle may contain a moon shaped crest of white flowers,[73] or a reed crown called Mukoot with peacock feathers (symbolism for Lord Krishna). The dancers forehead is marked with Tikka, and adorned with various jewelry such as the Allaka (head piece on which the tikka hangs). The eyes are ringed with Kajal (black eyeliner).[76]

Ear covers called Kapa or ear rings decorate the sides of the head, while necklace adorns the neck. The dancer wears a pair of armlets also called Bahichudi or Bajuband, on the upper arm. The wrist is covered with Kankana (bangles).[76] At the waist they wear an elaborate belt which ties down one end of the Sari. The ankles are decorated with a leather piece on top of which are bells (ghungroo).[74] The dancer's palms and soles may be painted with red coloured dye called the Alta.[76]

Modern Odissi male performers wear dhoti – a broadcloth tied around waist, pleated for movement, and tucked between legs; usually extends to knee or lower. Upper body is bare chested, and a long thin folded translucent sheet wrapping over one shoulder and usually tucked below a wide belt.[73]

Music and instruments

Odissi dance is accompanied by Odissi music. The primary Odissi ragas are Kalyana, Nata, Shree Gowda, Baradi, Panchama, Dhanashri, Karnata, Bhairavee and Shokabaradi.[77]

Odissi dance, states Ragini Devi, is a form of "visualized music", wherein the Ragas and Raginis, respectively the primary and secondary musical modes, are integrated by the musicians and interpreted through the dancer.[78] Each note is a means, has a purpose and with a mood in classical Indian music, which Odissi accompanies to express sentiments in a song through Parija.[78] This is true whether the performance is formal, or less formal as in Nartana and Natangi used during festive occasions and the folksy celebration of life.[78]

A distinctive feature of Odissi is that it includes both North and South Indian Ragas, which in 20th-century scholarship has been grouped as the Hindustani and the Carnatic music.[6] According to Alessandra Royo, Odissi music integrates the music styles of the two major Indian music concert traditions, and does not have a separate systematic classification like those found in the North and South Indian traditions.[79] According to Emmie Nijenhuis, Odissi music suggests performance arts and ideas were exchanged between the North and South India during the medieval era, and Odissi accepted both as a creative crucible of styles and ideas.[80]

Guru Ramahari Das, an eminent researcher and performer in Odissi music counters this incorrect assumption. He states, "Odissi music is a lot more lyrical as compared to Hindustani or Carnatic. Just like these two forms, it has its typical feel, its unique identity."[81] Pandit Damodar Hota also explicitly states the uniqueness of Odissi music thus, "Like the Saraswati River that formed the “triveni” along with the Ganga and the Yamuna, Odissi was a distinct stream of music like the Carnatic and Hindustani. It evolved from the ritualistic music of the Jagannath temple of Puri, and the 12th century saint-poet Jayadeva was a prominent practitioner of it." Multiple scholars have systematically countered the notion of Odissi being simply a mixture of two other styles that themselves were named in the twentieth century. Guru Dheeraj Mahapatra in his paper The Unique Features of Odissi Music: An Overview mentions the characteristics due to which a music can be called 'classical' and how Odissi music satisfies those criteria while establishing its distinctive nature.

An Odissi troupe comes with musicians and musical instruments. The orchestra consists of various regional musical instruments, such as the Mardala (barrel drum), harmonium, flute, sitar, violin, cymbals held in fingers and others.[6]

Styles

The Odissi tradition existed in three schools: Mahari, Nartaki, and Gotipua:

- Maharis were Oriya devadasis or temple girls, their name deriving from Maha (great) and Nari (girl), or Mahri (chosen) particularly those at the temple of Jagganath at Puri. Early Maharis performed Nritta (pure dance) and Abhinaya (interpretation of poetry) dedicated to various Hindu gods and goddesses, as well as Puranic mythologies and Vedic legends.[82] Later, Maharis especially performed dance sequences based on the lyrics of Jayadev's Gita Govinda.[82] This style is more sensuous and closer to the classical Sanskrit texts on dance, music and performance arts.[82]

- Gotipuas were boys dressed up as girls and taught the dance by the Maharis. This style included martial arts, athletics and acrobatics. Gotipuas danced to these compositions outside the temples and fairgrounds as folksy entertainment.[82]

- Nartaki dance took place in the royal courts, where it was prevalent before the British period.[83][84]

Schools, training and recognition

Odissi maestros and performers

Kelucharan Mohapatra, Gangadhar Pradhan, Pankaj Charan Das, Deba Prasad Das and Raghunath Dutta were the four major gurus who revived Odissi in the late forties and early fifties. Sanjukta Panigrahi was a leading disciple of Kelucharan Mohapatra who popularized Odissi by performing in India and abroad. In the mid-sixties, three other disciples of Kelucharan Mohapatra, Kumkum Mohanty and Sonal Mansingh, were known for their performances in India and abroad. Laximipriya Mohapatra performed a piece of Odissi abhinaya in the Annapurna Theatre in Cuttack in 1948, a show upheld as the first classical Odissi dance performance after its contemporary revival.[85] Guru Mayadhar Raut played a pivotal role in giving Odissi dance its classical status. He introduced Mudra Vinyoga in 1955 and Sancharibhava in the Odissi dance items, and portrayed Shringara Rasa in Gita Govinda Ashthapadis. His notable compositions include Pashyati Dishi Dishi and Priya Charu Shile, composed in 1961.[86]

IIT Bhubaneswar

Odissi has been included in Indian Institute of Technology Bhubaneswar's BTech syllabus since 2015 as the first Indian national technical institute to introduce any classical dance in syllabus.[87][88][89]

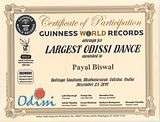

In Guinness World records

Guinness World Records has acknowledged the feat of the largest congregation of Odissi dancers in a single event. 555 Odissi dancers performed at the event hosted on 23 December 2011, in the Kalinga stadium, Bhubaneswar, Odisha. The dancers performed the Mangalacharan, Battu, Pallavi, Abhinay and Mokshya dance items from the Odissi repertoire.[90][91]

More than 1000 Odissi dancers performed at the World Cultural Festival[92][93] March 12, 2016. This is till date the largest congregation of Odissi dancers in a single event.

Odissi Centre at Oxford University

An Odissi dance centre has been opened from January, 2016, at the University of Oxford.[94] Known as Oxford Odissi Centre, it is an initiative of the Odissi dancer and choreographer Baisali Mohanty who is also a post-graduate scholar at the University of Oxford.[95]

Beside holding regular Odissi dance classes at its institution, the Oxford Odissi Centre also conducts Odissi dance workshops at other academic institutions in the United Kingdom.[96][97]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 Odissi Encyclopædia Britannica (2013)

- ↑ Williams 2004, pp. 83-84, the other major classical Indian dances are: Bharatanatyam, Kathak, Kuchipudi, Kathakali, Manipuri, Cchau, Satriya, Yaksagana and Bhagavata Mela.

- ↑ http://ccrtindia.gov.in/classicaldances.php Centre for Cultural Resources and Training (CCRT);

"Archived copy". Archived from the original on 14 October 2013. Retrieved 6 November 2013. Guidelines for Sangeet Natak Akademi Ratna and Akademi Puraskar - ↑ Peter J. Claus; Sarah Diamond; Margaret Ann Mills (2003). South Asian Folklore: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. p. 136. ISBN 978-0-415-93919-5.

- 1 2 3 Sunil Kothari; Avinash Pasricha (1990). Odissi, Indian classical dance art. Marg Publications. pp. 4–6, 41. ISBN 978-81-85026-13-8. , Quote: "There are other temples too in Orissa where the maharis used to dance. Besides the temple of Lord Jagannatha, maharis were employed in temples dedicated to Shiva and Shakti."

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Bruno Nettl; Ruth M. Stone; James Porter; et al. (1998). The Garland Encyclopedia of World Music: South Asia : the Indian subcontinent. Routledge. p. 520. ISBN 978-0-8240-4946-1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 James G. Lochtefeld (2002). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism: N-Z. The Rosen Publishing Group. pp. 484–485. ISBN 978-0-8239-3180-4.

- ↑ Richard Schechner (2010). Between Theater and Anthropology. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 65–66. ISBN 0-8122-0092-6.

- 1 2 Evangelos Kyriakidis (2007). The archaeology of ritual. Cotsen Institute of Archaeology, University of California Press. pp. 155–158. ISBN 978-1-931745-48-2.

- ↑ Sunil Kothari; Avinash Pasricha (1990). Odissi, Indian classical dance art. Marg Publications. pp. 9–10, 12. ISBN 978-81-85026-13-8. , Quote: The art of dance and music suffered on account of political instability, the Muslim invasion, the desecration of the temples and the loss of independence, the lack of patronage to both the maharis and the gotipua dancers..."

- ↑ Ragini Devi 1990, pp. 47-49.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Alexandra Carter (2013). Rethinking Dance History: A Reader. Routledge. pp. 144–145. ISBN 978-1-136-48500-8.

- ↑ Stephanie Arnold (2014). The Creative Spirit: An Introduction to Theatre. McGraw Hill. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-07-777389-2.

- ↑ Sunil Kothari; Avinash Pasricha (1990). Odissi, Indian classical dance art. Marg Publications. pp. 1–4, 76–77. ISBN 978-81-85026-13-8.

- ↑ Sunil Kothari; Avinash Pasricha (1990). Odissi, Indian classical dance art. Marg Publications. p. 50. ISBN 978-81-85026-13-8.

- ↑ Kapila Vatsyayan (1983). The square and the circle of the Indian arts. Roli Books International. pp. 57–58.

- 1 2 3 4 Alessandra Royo (2012). Pallabi Chakravorty, Nilanjana Gupta, ed. Dance Matters: Performing India on Local and Global Stages. Routledge. p. 267. ISBN 978-1-136-51613-9.

- ↑ Axel Michaels; Christoph Wulf (2012). Images of the Body in India: South Asian and European Perspectives on Rituals and Performativity. Routledge. p. 192. ISBN 978-1-136-70392-8.

- ↑ Ian Watson (2003). Towards a Third Theatre: Eugenio Barba and the Odin Teatret. Routledge. pp. xii–xiii. ISBN 978-1-134-79755-4.

- ↑ Sunil Kothari; Avinash Pasricha (1990). Odissi, Indian classical dance art. Marg Publications. pp. 32–33, 48–49, 68. ISBN 978-81-85026-13-8.

- 1 2 3 Kathleen Kuiper (2010). The Culture of India. The Rosen Publishing Group. p. 278. ISBN 978-1-61530-149-2.

- 1 2 3 Natalia Lidova 2014.

- ↑ Tarla Mehta 1995, pp. xxiv, 19–20.

- ↑ Wallace Dace 1963, p. 249.

- ↑ Emmie Te Nijenhuis 1974, pp. 1–25.

- ↑ Kapila Vatsyayan 2001.

- ↑ Guy L. Beck (2012). Sonic Liturgy: Ritual and Music in Hindu Tradition. University of South Carolina Press. pp. 138–139. ISBN 978-1-61117-108-2.

Quote: "A summation of the signal importance of the Natyasastra for Hindu religion and culture has been provided by Susan Schwartz, "In short, the Natyasastra is an exhaustive encyclopedic dissertation of the arts, with an emphasis on performing arts as its central feature. It is also full of invocations to deities, acknowledging the divine origins of the arts and the central role of performance arts in achieving divine goals (...)".

- ↑ Coormaraswamy and Duggirala (1917). "The Mirror of Gesture". Harvard University Press. p. 4. ; Also see chapter 36

- 1 2 Sunil Kothari; Avinash Pasricha (1990). Odissi, Indian classical dance art. Marg Publications. pp. 5–6. ISBN 978-81-85026-13-8.

- ↑ Sunil Kothari; Avinash Pasricha (1990). Odissi, Indian classical dance art. Marg Publications. pp. 13–16, 31–32. ISBN 978-81-85026-13-8.

- ↑ Benudhar Patra (2008), Merchants, Guilds and Trade in Ancient India: An Orissan Perspective, Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute, Volume 89, pages 133-168

- ↑ Hathigumpha inscription Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine. South Dakota State University, Epigraphia Indica, Vol. XX (1929-30)

- ↑ J. F. Fleet (1910), The Hathigumpha Inscription, The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, (Jul., 1910), Cambridge University Press, pages 824-828

- ↑ P. Yule; M. Bemmann (1988). "Klangsteine aus Orissa-Die frühesten Musikinstrumente Indiens?". Archaeologia Musicalis. 2.1: 41–50.

- ↑ Bruno Nettl; Ruth M. Stone; James Porter; et al. (1998). The Garland Encyclopedia of World Music: South Asia : the Indian subcontinent. Taylor & Francis. p. 319. ISBN 978-0-8240-4946-1.

- ↑ Sunil Kothari; Avinash Pasricha (1990). Odissi, Indian classical dance art. Marg Publications. pp. 13–15. ISBN 978-81-85026-13-8.

- ↑ DB Mishra (2006), Orissan Inscriptions Orissa Review

- ↑ Alexandra Carter (2013). Rethinking Dance History: A Reader. Routledge. pp. 147–148. ISBN 978-1-136-48500-8.

- ↑ Kapila Vatsyayan (1982). Dance In Indian Painting. Abhinav Publications. pp. 73–78. ISBN 978-0391022362.

- ↑ Sunil Kothari; Avinash Pasricha (1990). Odissi, Indian classical dance art. Marg Publications. pp. 66–67. ISBN 978-81-85026-13-8.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Reginald Massey 2004, pp. 210-212.

- ↑ Alice Boner; Sadāśiva Rath Śarmā (1966). Silpa Prakasa Medieval Orissan Sanskrit Text on Temple Architecture. Brill Academic. pp. 74–80, 52, 154.

- 1 2 3 Archana Verma (2011). Performance and Culture: Narrative, Image and Enactment in India. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 43–57. ISBN 978-1-4438-2832-1.

- ↑ Dhirendranath Patnaik (1990). Odissi dance. Orissa Sangeet Natak Adademi. pp. 68–69.

- ↑ Stephanie Burridge (2006). Shifting sands: dance in Asia and the Pacific. Australian Dance Council. p. 32. ISBN 978-1-875255-15-3.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Alexandra Carter (2013). Rethinking Dance History: A Reader. Routledge. pp. 148–149. ISBN 978-1-136-48500-8.

- ↑ Ragini Devi 1990, p. 142.

- 1 2 3 Mary Ellen Snodgrass (2016). The Encyclopedia of World Folk Dance. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 165–168. ISBN 978-1-4422-5749-8.

- 1 2 Margaret E. Walker (2016). India's Kathak Dance in Historical Perspective. Routledge. pp. 94–98. ISBN 978-1-317-11737-7.

- 1 2 Alexandra Carter (2013). Rethinking Dance History: A Reader. Routledge. pp. 145–146. ISBN 978-1-136-48500-8.

- ↑ Amrit Srinivasan (1983). "The Hindu Temple-dancer: Prostitute or Nun?". The Cambridge Journal of Anthropology. 8 (1): 73–99. JSTOR 23816342.

- ↑ Leslie C. Orr (2000). Donors, Devotees, and Daughters of God: Temple Women in Medieval Tamilnadu. Oxford University Press. pp. 5, 8–17. ISBN 978-0-19-535672-4.

- ↑ Pallabi Chakravorty; Nilanjana Gupta (2012). Dance Matters: Performing India on Local and Global Stages. Routledge. p. 30. ISBN 978-1-136-51612-2.

- ↑ Debra Craine; Judith Mackrell (2010). The Oxford Dictionary of Dance. Oxford University Press. p. 420. ISBN 978-0199563449.

- ↑ David Dennen. "The Naming of Odissi: Changing Conceptions of Music in Odisha".

- 1 2 Reginald Massey 2004, p. 209.

- ↑ Alexandra Carter (2013). Rethinking Dance History: A Reader. Routledge. p. 149. ISBN 978-1-136-48500-8.

- ↑ Archana Verma (2011). Performance and Culture: Narrative, Image and Enactment in India. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 43–47. ISBN 978-1-4438-2832-1.

- ↑ Judith Lynne Hanna (1988). Dance, Sex, and Gender: Signs of Identity, Dominance, Defiance, and Desire. University of Chicago Press. pp. 102–103. ISBN 978-0-226-31551-5.

- ↑ Judith Lynne Hanna (1988). Dance, Sex, and Gender: Signs of Identity, Dominance, Defiance, and Desire. University of Chicago Press. pp. 98–106. ISBN 978-0-226-31551-5.

- 1 2 3 4 Bruno Nettl; Ruth M. Stone; James Porter; et al. (1998). The Garland Encyclopedia of World Music: South Asia : the Indian subcontinent. Routledge. pp. 519–521. ISBN 978-0-8240-4946-1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Reginald Massey 2004, pp. 207-214.

- 1 2 Ellen Koskoff (2008). The Concise Garland Encyclopedia of World Music: The Middle East, South Asia, East Asia, Southeast Asia. Routledge. p. 955. ISBN 978-0-415-99404-0.

- 1 2 Janet Descutner (2010). Asian Dance. Infobase. pp. 45–46. ISBN 978-1-4381-3078-1.

- ↑ Catherine B. Asher (1995). India 2001: Reference Encyclopedia. South Asia Book. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-945921-42-4.

- 1 2 3 Kapila Vatsyayan 1974, pp. 38-39.

- ↑ Ragini Devi 1990, pp. 144-145.

- ↑ Kapila Vatsyayan 1974, pp. 38, 65.

- ↑ Kapila Vatsyayan 1974, p. 36.

- ↑ Kapila Vatsyayan 1974, pp. 35-37.

- 1 2 3 4 Sunil Kothari; Avinash Pasricha (1990). Odissi, Indian classical dance art. Marg Publications. pp. 64–67. ISBN 978-81-85026-13-8.

- ↑ Dhirendranath Patnaik (1990). Odissi dance. Orissa Sangeet Natak Adademi. pp. 112–113.

- 1 2 3 4 Bruno Nettl; Ruth M. Stone; James Porter; et al. (1998). The Garland Encyclopedia of World Music: South Asia : the Indian subcontinent. Taylor & Francis. p. 521. ISBN 978-0-8240-4946-1.

- 1 2 Anne-Marie Gaston (2012). Hillary P. Rodrigues, ed. Studying Hinduism in Practice. Routledge. p. 81. ISBN 978-1-136-68097-7.

- ↑ Dhirendranath Patnaik (1990). Odissi dance. Orissa Sangeet Natak Adademi. pp. 9–11.

- 1 2 3 Dhirendranath Patnaik (1990). Odissi dance. Orissa Sangeet Natak Adademi. pp. 113–115.

- ↑ "Culture Department". Orissaculture.gov.in. Retrieved 2012-05-19.

- 1 2 3 Ragini Devi 1990, pp. 147-149.

- ↑ Alessandra Royo (2012). Pallabi Chakravorty, Nilanjana Gupta, ed. Dance Matters: Performing India on Local and Global Stages. Routledge. p. 277 with footnote 14. ISBN 978-1-136-51613-9.

- ↑ Emmie te Nijenhuis (1977). Musicological literature. Harrassowitz. pp. 32–33. ISBN 978-3-447-01831-9.

- ↑ David Dennen (2010; revised 2012), The Third Stream: Odissi Music, Regional Nationalism, and the Concept of “Classical”

- 1 2 3 4 Sunil Kothari; Avinash Pasricha (1990). Odissi, Indian classical dance art. Marg Publications. pp. 41–49. ISBN 978-81-85026-13-8.

- ↑ Alessandra Lopez y Royo, "The reinvention of odissi classical dance as a temple ritual," published in The Archaeology of Ritual ed. Evangelos Kyriakidis, Cotsen Institute of Archaeology, UCLA 2007

- ↑ Dhirendranath Patnaik (1990). Odissi dance. Orissa Sangeet Natak Adademi. pp. 84–85.

- ↑ "Steps to success". The Telegraph. Calcutta, India. 9 August 2010.

- ↑ Kaktikar, A. Odissi Yaatra: The Journey of Guru Mayadhar Raut. Delhi: B. R. Rhythms. 2010. ISBN 978-81-88827-21-3.

- ↑ Pradhan, Ashok (11 September 2015). "IIT Bhubaneswar becomes first IIT in country to introduce dance as BTech subject". Times of India. Retrieved 13 September 2015.

- ↑ Barik, Satyasundar (12 September 2015). "IIT-Bhubaneswar to train students in Odissi too". The Hindu. Retrieved 13 September 2015.

- ↑ "IIT-Bhubaneswar Becomes First IIT to Introduce Odissi as a Course". New Indian Express. 12 September 2015. Retrieved 13 September 2015.

- ↑ "Odissi dancers enter Guinness". newindianexpress.com. Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- ↑ thesundayindian.com: Guinness World Records enlists Odissi dance show

- ↑ "LIVE: Watch - Art of Living's World Culture Festival 2016 – Day 2". india.com. 12 March 2016. Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- ↑ Ayaskant. "Sri Sri to visit Odisha to prepare for World Culture Festival - OdishaSunTimes.com". odishasuntimes.com. Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- ↑ "Odissi beats to resonate at Oxford University". telegraphindia.com. Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- ↑ Ayaskant. "Odissi Centre to open at Oxford University from Jan - OdishaSunTimes.com". odishasuntimes.com. Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- ↑ "The Pioneer". www.dailypioneer.com. Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- ↑ "Kalinga TV on Facebook". KalingaTV. Retrieved 27 March 2018.

Bibliography

- Odissi : What, Why and How… Evolution, Revival and Technique, by Madhumita Raut. Published by B. R. Rhythms, Delhi, 2007. ISBN 81-88827-10-X.

- Odissi Yaatra: The Journey of Guru Mayadhar Raut, by Aadya Kaktikar (ed. Madhumita Raut). Published by B. R. Rhythms, Delhi, 2010. ISBN 978-81-88827-21-3.

- Odissi Dance, by Dhirendranath Patnaik. Published by Orissa Sangeet Natak Akademi, 1971.

- Odissi – The Dance Divine, by Ranjana Gauhar and Dushyant Parasher. Published by Niyogi Books, 2007. ISBN 81-89738-17-8.

- Odissi, Indian Classical Dance Art: Odisi Nritya, by Sunil Kothari, Avinash Pasricha. Marg Publications, 1990. ISBN 81-85026-13-0.

- Perspectives on Odissi Theatre, by Ramesh Prasad Panigrahi, Orissa Sangeet Natak Akademi. Published by Orissa Sangeet Natak Akademi, 1998.

- Abhinaya-chandrika and Odissi dance, by Maheshwar Mahapatra, Alekha Chandra Sarangi, Sushama Kulshreshthaa, Maya Das. Published by Eastern Book Linkers, 2001. ISBN 81-7854-010-X.

- Rethinking Odissi, by Dinanath Pathy. Published by Harman Pub. House, 2007. ISBN 81-86622-88-8.

- Natalia Lidova (2014). "Natyashastra". Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/obo/9780195399318-0071.

- Natalia Lidova (1994). Drama and Ritual of Early Hinduism. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-1234-5.

- Ragini Devi (1990). Dance Dialects of India. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-0674-0.

- Williams, Drid (2004). "In the Shadow of Hollywood Orientalism: Authentic East Indian Dancing" (PDF). Visual Anthropology. Routledge. 17 (1): 69–98. doi:10.1080/08949460490274013.

- Tarla Mehta (1995). Sanskrit Play Production in Ancient India. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-1057-0.

- Fergusson, James (1880). The Caves Temples of India. W. H. Allen. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- Michell, George l (15 October 2014). Temple Architecture and Art of the Early Chalukyas: Badami, Mahakuta, Aihole, Pattadakal. Niyogi Books. ISBN 978-93-83098-33-0.

- Reginald Massey (2004). India's Dances: Their History, Technique, and Repertoire. Abhinav Publications. ISBN 978-81-7017-434-9.

- Emmie Te Nijenhuis (1974). Indian Music: History and Structure. BRILL Academic. ISBN 90-04-03978-3.

- Kapila Vatsyayan (2001). Bharata, the Nāṭyaśāstra. Sahitya Akademi. ISBN 978-81-260-1220-6.

- Kapila Vatsyayan (1977). Classical Indian dance in literature and the arts. Sangeet Natak Akademi. OCLC 233639306. , Table of Contents

- Kapila Vatsyayan (1974), Indian classical dance, Sangeet Natak Akademi, OCLC 2238067

- Kapila Vatsyayan (2008). Aesthetic theories and forms in Indian tradition. Munshiram Manoharlal. ISBN 978-8187586357. OCLC 286469807.

- Kapila Vatsyayan. Dance In Indian Painting. Abhinav Publications. ISBN 978-81-7017-153-9.

- Wallace Dace (1963). "The Concept of "Rasa" in Sanskrit Dramatic Theory". Educational Theatre Journal. 15 (3): 249. doi:10.2307/3204783. JSTOR 3204783.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Odissi. |

- Odissi solo performance: Nitisha Nanda, Arabhi Pallav, New Delhi 2013

- Odissi group dance: Megh Pallavi, Vancouver 2014

- Maryam Shakiba - Odissi Dance - Manglacharan Ganesh Vandana Pushkar 2014

- Odissi links at the Open Directory

- Odissi schools, Classical Indian Dance Portal

- The annotated Odissi Dance Archive on Pad.ma

- History of Odissi and Geeta Govinda JN Dhar, Orissa Review