No-till farming

(NRCS_Photo_Gallery).jpg) Young soybean plants thrive in and are protected by the residue of a wheat crop. This form of no till farming provides good protection for the soil from erosion and helps retain moisture for the new crop. |

|

| Agriculture |

|---|

| History |

| On land |

| In water |

| Related |

| Lists |

| Categories |

|

|

|

No-till farming (also called zero tillage or direct drilling) is a way of growing crops or pasture from year to year without disturbing the soil through tillage. No-till is an agricultural technique which increases the amount of water that infiltrates into the soil, the soil's retention of organic matter and its cycling of nutrients. In many agricultural regions, it can reduce or eliminate soil erosion. It increases the amount and variety of life in and on the soil, including disease-causing organisms and disease organisms. The most powerful benefit of no-tillage is improvement in soil biological fertility, making soils more resilient. Farm operations are made much more efficient, particularly improved time of sowing and better trafficability of farm operations.

Tillage remains relevant in agriculture today, but the success of no-till methods in many contexts keeps farmers aware that multiple options exist. In some cases low-till methods combine aspects of till and no-till methods. For example, some approaches may use a limited amount of shallow disc harrowing but no plowing.

Background

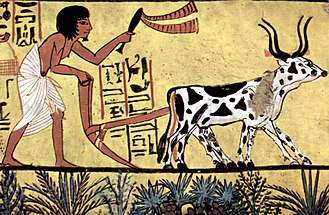

Tillage is the agricultural preparation of soil by mechanical agitation, typically killing the plants earlier in place.[1] Tilling can create a flat seed bed or one that has formed areas, such as rows or raised beds, to enhance the growth of desired plants. It is an ancient technique with clear evidence of its use since at least 3000 B.C.E.[2]

The effects of tillage can include soil compaction; loss of organic matter; degradation of soil aggregates; death or disruption of soil microbes and other organisms including mycorrhizae, arthropods, and earthworms;[3] and soil erosion where topsoil is washed or blown away.

Origin in modern farms

The idea of modern no-till farming started in the 1940s with Edward H. Faulkner, author of Plowman's Folly,[4] but it wasn't until the development of several chemicals after WWII that various researchers and farmers started to try out the idea. The first adopters of no-till include Klingman (North Carolina), Edward Faulkner, L.A. Porter (New Zealand), Harry and Lawrence Young (Herndon, Kentucky), the Instituto de Pesquisas Agropecuarias Meridional (1971 in Brazil) with Herbert Bartz.[5]

Adoption in the United States

No-till farming is widely used in the United States and the number of acres managed in this way continues to grow. This growth is supported by a decrease in costs related to tillage; no-till management results in fewer passes with equipment for approximately equal harvests, and the crop residue prevents evaporation of rainfall and increases water infiltration into the soil.[6]

Issues

Profit, economics, yield

Studies have found that no-till farming can be more profitable[7][8] if performed correctly.

It reduces labour,[9] fuel,[10] irrigation[11] and machinery costs.[8] No-till can increase yield because of higher water infiltration and storage capacity, and less erosion.[12] Another benefit of no-till is that because of the higher water content, instead of leaving a field fallow it can make economic sense to plant another crop instead.[13]

As sustainable agriculture becomes more popular, monetary grants and awards are becoming readily available to farmers who practice conservation tillage. Some large energy corporations which are among the greatest generators of fossil-fuel-related pollution may purchase carbon credits, which can encourage farmers to engage in conservation tillage.[14][15] Under such schemes, the farmers' land is legally redefined as a carbon sink for the power generators' emissions. This helps the farmer in several ways , and it helps the energy companies meet regulatory demands for reduction of pollution, specifically carbon emissions.

No-till farming can increase organic (carbon based)[12] matter in the soil, which is a form of carbon sequestration. However, there is debate over whether this increased sequestration detected in scientific studies of no-till agriculture is actually occurring, or is due to flawed testing methods or other factors.[16] Regardless of this debate, a case can still be made for no-till, in the form of reduction in fossil fuel use, less erosion and better soil quality.

Environmental

Greenhouse gases

No-till farming has carbon sequestration potential through storage of soil organic matter in the soil of crop fields.[17] Tilling inverts soil layers, mixes in air, and greatly increases microbial activity. Organic matter breaks down much faster, releasing its carbon into the atmosphere. Also, farm tractors emit carbon dioxide.

Cropland soils are ideal as a carbon sink, as they have been depleted of carbon in most areas. Tillage and conventional farming have released an estimated 78 billion metric tonnes of carbon,[18] by removing crop residues such as left over corn stalks and adding chemical fertilizers. Without tillage, residues decompose where they lie, and growing of winter cover crops can slow and reverse carbon loss.

However, there is evidence that no-till systems still lose carbon over time. A 2014 study led by Ken Olson of University of Illinois concluded that this differing result occurs in part because tested soil samples need to include the full depth of rooting, 1–2 meters. He said, “That no-till subsurface layer is often losing more soil organic carbon stock over time than is gained in the surface layer.”. Also, there has not been a uniform definition of soil organic carbon sequestration among researchers.[19] The study concludes, "Additional investments in soil organic carbon (SOC) research is needed to better understand the agricultural management practices that are most likely to sequester SOC or at least retain more net SOC stocks."[20]

Besides reducing carbon emissions, no-till farming reduces nitrous oxide (N2O) emissions by 40-70%, depending on rotation.[21][22] Nitrous oxide is a potent greenhouse gas, 300 times stronger than CO2, and stays in the atmosphere for 120 years.[23] Fertilizing farmlands with (excessive) nitrogen increases the release of nitrous oxide.

Soil water

No-till farming improves soil quality (soil function), carbon, organic matter, aggregates,[24] protecting from erosion,[25] evaporation of water,[26] and structural breakdown. Reducing of tillage reduces compaction of soil. This can help reduce soil erosion almost to soil production rates.[27]

Recently, researchers at the Agricultural Research Service of the United States Department of Agriculture found that no-till farming makes soil much more stable than plowed soil. Their conclusions draw from over 19 years of collaborated tillage studies. No-till stores more carbon in the soil and carbon in the form of organic matter is a key factor in holding soil particles together. The first inch of no-till soil is two to seven times less vulnerable than that of plowed soil. The practice of no-till farming is especially beneficial to Great Plains farmers because of its avoidance of erosion.[28]

Crop residues left intact help both natural precipitation and irrigation water to infiltrate the soil. Residue also limits evaporation, conserving water for plant growth. Evaporation from tilling reduces the amount of water by around 1/3 to 3/4 inches (0.85 to 1.9 cm) per pass.[26] By reducing soil compaction and no tillage-pan, the soil absorbs more water, and roots grow deeper, reaching more water.

Biota and wildlife

No-till farming leaves soil intact and crop residue on the field. Soil layers and soil biota, remain in their natural state. No-tilled fields often have more beneficial insects and annelids,[29] more organic material and microbial content, and variety of wildlife.[30] This is the result of improved cover, reduced traffic and the reduced chance of destroying ground nesting birds and animals (plowing destroys all of them).

No ploughing also means less airborne dust.

Albedo

Tillage lowers the albedo of croplands. The potential for global cooling as a result of decreased Albedo in no till croplands is similar in magnitude to the biogeochemical (carbon sequestration) potential.[31]

Historical artifacts

Tilling regularly damages ancient structures under the soil such as long barrows. In the UK, half of the long barrows in Gloucestershire and almost all the burial mounds in Essex have been damaged. According to English Heritage modern tillage techniques have done as much damage in the last six decades as traditional tilling did in the previous six centuries. By using no-till methods these structures can be preserved and can be properly investigated instead.[32]

Cost

Equipment

No-till farming requires specialized seeding equipment such as seed drills, to plant seeds into undisturbed crop residues and soil. The cost can be offset by selling plows and tractors, but farmers often keep their old equipment while trying out no-till farming. This would result in more money being invested into equipment in the short term (until old equipment is sold off).[33]

Drainage

If a soil has poor drainage, it may need drainage tiles or other devices to remove excess water under no-till. Water infiltration improves after 5-8 years of no-till farming, so farmers may want to wait before investing in such an expensive system.

Gullies can be a problem in the long-term. While much less soil is displaced by no-till farming, any drainage gulleys that do form deepen each year since they are not smoothed out by plowing.[34] This may necessitate either sod drainways, waterways, permanent drainways, cover crops, etc. Gully formation can be avoided entirely with proper water management practices, including the creation of swales on contour.

Increased chemical use

One of the purposes of tilling is to remove weeds. No-till farming does change weed composition drastically. Faster growing weeds may no longer be a problem in the face of increased competition, but shrubs and trees may begin to grow eventually.

Some farmers attack this problem with a “burn-down” herbicide such as glyphosate in lieu of tillage for seedbed preparation and because of this, no-till is often associated with increased chemical use in comparison to traditional tillage based methods of crop production. However, there are many agroecological alternatives to increased chemical use, such as winter cover crops and the mulch cover they provide, soil solarization or burning.

Management

No-till farming requires some different skills than conventional farming. As with any production system, if done incorrectly, yields can drop. A combination of technique, equipment, pesticides, crop rotation, fertilization, and irrigation have to be used for local conditions.

Cover crops

In no-till occasionally uses cover crops to help control weeds and increase nutrients in the soil (by using legumes)[35] or by using plants with long roots to pull mobile nutrients to the surface from lower layers of the soil. Cover crops then need to be killed so that the newly planted crops can get enough light, water, nutrients, etc.[36][37] This can be done by rollers, crimper, choppers and other ways.[38]

Crop rotation

With no-till farming, residue from the previous years crops lie on the surface of the field, cooling it and increasing the moisture. This can increase or decrease disease or cause it to vary[39] compared to tillage farming.[40] To reduce weeds, pests and disease, crop rotation is used. Planting different crops year after year denies a pest or pathogen population a supply of whatever food it is adapted to consume.

Organic no-till

Some farmers who practice organic management often place ordinary, non-dyed corrugated cardboard on seed-beds and vegetable areas. Used correctly, cardboard placed on a specific area can

- keep important fungal hyphae and microorganisms in the soil intact

- prevent recurring weeds from popping up

- increase residual nitrogen and plant nutrients by top-composting plant residues and

- create valuable topsoil for next year's seeds or transplants.

Plant residues (left over plant matter originating from cover crops, grass clippings, original plant life etc.) rots while underneath the cardboard so long as it remains moist enough. This rotting attracts worms and other beneficial microorganisms to the site of decomposition, and over a few seasons (usually Spring to Fall or Fall to Spring) and up to a few years, creates a layer of rich topsoil. Plants can then be seeded into the soil in spring, or holes can be cut into the cardboard to allow transplanting. Using this method in conjunction with other sustainable practices such as composting/vermicompost, cover crops and rotations are often considered beneficial to both land and those who take from it.

On fields too large to manually apply a residue with a high carbon-to-nitrogen ratio, a cover crop may be used to produce a similar effect. The cover crop may be killed by mowing or by crimping the stalk, as with a roller/crimper.[41] The residue is then planted through, and left as a mulch to retard weed growth and slowly release the nutrients contained therein. Cover crops typically must be crimped when they enter the flowering/pollination stage.[42]

Water issues

No-till farming dramatically reduces erosion in a field. While much less soil is displaced, any gullies that form get deeper each year instead of being smoothed out by regular plowing. This may be handled by creating sod drainways, waterways, permanent drainways, cover crops, etc.[43]

A problem in some fields is water saturation in soils. Switching to no-till farming corrects drainage because of the qualities of soil under continuous no-till include a higher water infiltration rate.[44]

Equipment

It is very important to have planting equipment that can properly penetrate through the residue, into the soil and prepare a good seedbed.[45] No-till farming requires much less maximum power from farm tractors, so equipment (a tractor) can be smaller than under tilling.[46] Using a smaller, lighter tractor has the added benefit of reducing compaction.

Soil temperature

Another problem of no-till farming is that in spring, the soil both warms and dries more slowly, which may delay planting. The slower warming is due to crop residue being a lighter color than the soil which would be exposed in conventional tillage, which then absorbs less solar energy. This can be managed by using row cleaners on a planter.[47] Since the soil can be cooler, harvest can occur a few days later than a conventionally tilled field. Note: A cooler soil is also a benefit because water doesn't evaporate as fast.

Residue

On some crops, like continuous no-till corn, the thickness of the residue on the surface of the field can become a problem without proper preparation and/or equipment.

Fertilizer

One of the most common yield reducers is nitrogen being immobilized in the crop residue, which can take a few months to several years to decompose, depending on the crop's C to N ratio and the local environment.[48] Fertilizer needs to be applied at a higher rate during the transition period while the soil rebuilds its organic matter. The nutrients in the organic matter are eventually released into the soil, so this is only a concern during the transition time frame (4–5 years for Kansas, USA). An innovative solution to this problem is to integrate animal husbandry in various ways to aid in decomposition.[49]

Misconceptions

Need to fluff the soil

Although no-till farming often causes a slight increase in soil bulk density, periodic tilling is not needed to “fluff” the soil back up. No-till farming mimics the natural conditions under which most soils formed more closely than any other method of farming, in that the soil is left undisturbed except to place seeds in a position to germinate.

Similar terms

No-till farming is not equivalent to conservation tillage or strip tillage. Conservation tillage is a group of practices that reduce the amount of tillage needed. No-till and strip tillage are both forms of conservation tillage. No-till is the practice of never tilling a field. Tilling every other year is called rotational tillage.

See also

- Conventional tillage

- Carbon farming

- Broadfork, a tool to aerate the soil without overturning

- Masanobu Fukuoka, one of the pioneers of no-till grain cultivation

- Cereal (Macrobiotic) agriculture, uses minimal tillage[50][51]

- Natural farming

- Conservation agriculture

- No-dig gardening

- Permaculture

- Strip-till

References

- ↑ "Tillage". Wikipedia. 2016-11-15.

- ↑ name=history of tillage Archived 2016-01-07 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Preston Sullivan (2004). "Sustainable Soil Management". Attra.ncat.org. Archived from the original on 2007-08-15. Retrieved 2010-05-09.

- ↑ "Is Organic Farming Better for the Environment? | Genetic Literacy Project". geneticliteracyproject.org. Retrieved 2018-01-09.

- ↑ Derpsch, Rolf. "A short History of No-till". NO- TILLAGE. Archived from the original on 1 May 2011. Retrieved 26 March 2011.

- ↑ Plumer, Brad (9 November 2013). "No-till farming is on the rise. That's actually a big deal" – via www.washingtonpost.com.

- ↑ D.L. Beck, J.L. Miller, and M.P. Hagny "Successful No-Till on the Central and Northern Plains"

- 1 2 Derpsch, Rolf. "Economics of No-till farming. Experiences from Latin America" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-27. Retrieved 2010-05-09.

- ↑ Time savings from no-till are the result of fewer passes over a field being needed and less time for each pass (its faster to pull a sprayer over a field than a plow through it).

- ↑ NRCS. "USDA-NRCS Energy Consumption Awareness Tool: Tillage". ecat.sc.egov.usda.gov.

- ↑ Network, University of Nebraska-Lincoln | Web Developer (2015-09-17). "How Tillage and Crop Residue Affect Irrigation Requirements - UNL CropWatch, April 5, 2013". CropWatch. Retrieved 2018-01-31.

- 1 2 "Better Management Practices: No-Till/Conservation Tillage". WWF. Retrieved 4 April 2011.

- ↑ "Yield & Economic Comparisons: University Research Trials" (PDF). p. 1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 May 2005.

- ↑ "How to Utilize Carbon Credits" (PDF). extension.umn.edu. 7 August 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 1 March 2015.

- ↑ "Carbon Credit Program". National Farmers Union. Archived from the original on 2010-05-07. Retrieved 2010-05-09.

- ↑ Baker et al. (2007) Tillage and soil carbon sequestration—What do we really know?. Journal of Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment. Volume 118, Issues 1–4

- ↑ Carbon sequestration in two Brazilian Cerrado soils under no-till Bayer, C | Martin-Neto, L | Mielniczuk, J | Pavinato, A | Dieckow, J Soil and Tillage Research [Soil Tillageyhjs.]. Vol. 86, no. 2, p.237-245. Apr 2006.

- ↑ Lal, Rattan. "No-Till Farming Offers A Quick Fix To Help Ward Off Host Of Global Problems". Researchnews.osu.edu. Archived from the original on 2010-04-27. Retrieved 2010-05-09.

- ↑ "No-till soil organic carbon sequestration rates published". Science Daily. Retrieved 2012-04-21. April 18, 2014.

- ↑ Olson K.R., Al-Kaisi M.M., Lal R., Lowery B. (2014). Experimental Consideration, Treatments, and Methods in Determining Soil Organic Carbon Sequestration Rates. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 78:2:pp.348-360. (Open access).

- ↑ Omonode, R. A.; Smith, D. R.; Gál, A.; Vyn, T. J. (2011). "Soil Nitrous Oxide Emissions in Corn following Three Decades of Tillage and Rotation Treatments". Soil Science Society of America Journal. 75: 152. doi:10.2136/sssaj2009.0147.

- ↑ Study: No-till farming reduces greenhouse gas San-Francisco Chronicle

- ↑ Wallheimer, Brian. "No-till, rotation can limit greenhouse gas emissions from farm fields". physorg.com. Retrieved 26 March 2011.

- ↑ "Soil Management - The Soil Scientist". Extension.umn.edu. Archived from the original on 2010-03-22. Retrieved 2010-05-09.

- ↑ "Conservation Tillage". Monsanto.com. Archived from the original on June 20, 2008. Retrieved 2010-05-09.

- 1 2 http://cropwatch.unl.edu/input$/notill_irrigation.htm. Retrieved April 17, 2009. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Montgomery, David R. "Is agriculture eroding civilization's foundation?" (PDF). GSA Today. 17 (10). doi:10.1130/gsat01710a.1.

- ↑ Blanco-Canqui, H.; Mikha, M. M.; Benjamin, J. G.; Stone, L. R.; Schlegel, A. J.; Lyon, D. J.; Vigil, M. F.; Stahlman, P. W. (2009). "Regional Study of No-Till Impacts on Near-Surface Aggregate Properties that Influence Soil Erodibility". Soil Science Society of America Journal. 73 (4): 1361. doi:10.2136/sssaj2008.0401.

- ↑ Chan, K.Y. "An overview of some tillage impacts on earthworm population abundance and diversity — implications for functioning in soils". Soil and Tillage Research. 57 (4): 179–191. doi:10.1016/S0167-1987(00)00173-2.

- ↑ D. B. Warburton and W. D. Klimstra; D. B. Warburton; W. D. Klimstra (1984-09-01). "Wildlife use of no-till and conventionally tilled corn fields". 39 (5). Journal of Soil and Water Conservation. Retrieved 2010-05-09.

- ↑ D. B. Lobell, G. Bala and P. B. Duffy; D. B. Lobell; G. Bala; P. B. Duffy (2006-03-23). "Biogeophysical impacts of cropland management changes on climate" (PDF). 33. GEOPHYSICAL RESEARCH LETTERS. Retrieved 2012-07-02.

- ↑ "Ripping Up History" July 2003 English Heritage

- ↑ "Search - AgManager.info" (PDF). www.agmanager.info.

- ↑ Elton Robinson (Aug 1, 2008). "Tilling ephemeral gullies can cost you soil". Deltafarmpress.com. Archived from the original on 2008-08-05. Retrieved 2010-05-09.

- ↑ "TIPS FOR NO-TILL PLANTING INTO COVER CROPS" Penn. State University

- ↑ "No-Till Revolution". Rodale Institute. Retrieved 2010-05-09.

- ↑ George Kuepper (June 2001). "Pursuing Conservation Tillage Systems for Organic Crop Production". Attra.ncat.org. Archived from the original on June 12, 2008. Retrieved 2010-05-09.

- ↑ "Crimping Cover Crops". Conservation Currents. Northern Virginia Soil and Water Conservation District. Retrieved 26 March 2011.

- ↑ Daryl D. Buchholz (October 1993). "No-Till Planting Systems". University of Missouri Extension. Retrieved 2010-05-09.

- ↑ "Tillage has less effect on crop diseases than other factors". Top Crop Manager. Archived from the original on 2011-10-07. Retrieved 2011-12-04.

- ↑ "Organic No-Till | Rodale Institute". rodaleinstitute.org. Retrieved 2017-01-16.

- ↑ "INTRODUCTION TO COVER CROP ROLLING & THE VAUSDA CRIMPER ROLLER DEMONSTRATION PROJECT" (PDF).

- ↑ Elton Robinson "Tilling ephemeral gullies can cost you soil" Archived 2008-08-05 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Kindig, Wendy. "No till/Cover Crops Articles". York County Conservation District. Retrieved 2 April 2011.

- ↑ "Mississippi State University Extension Service -". msucares.com.

- ↑ Casady, William W. "G1236 Farming With One Tractor"

- ↑ Network, University of Nebraska-Lincoln | Web Developer (2015-09-17). "Setting Planting Equipment for Successful No-till". CropWatch. Retrieved 2018-01-23.

- ↑ Hartman, Murray. "Direct Seeding: Estimating the Value of Crop Residues". Government of Alberta: Agriculture and Rural Development. Retrieved 22 March 2011.

- ↑ Tallman, Susan. "No-Till Case Study, Richter Farm: Cover Crop Cocktails in a Forage-Based System". National Sustainable Agriculture Information Service. NCAT-ATTRA. Retrieved 8 April 2013.

- ↑ "Macrobiotic agriculture".

- ↑ Handboek ecologisch tuinieren by Herman Van Boxem

Further reading

- Wright, Sylvia (Winter 2006). "Pay Dirt". UC Davis Magazine. pp. 24–27.

- Philpott, Tom (2013-09-09). "One Weird Trick to Fix Farms Forever". Mother Jones. Retrieved 2014-03-14.

- Montgomery, David R. (2007). Dirt: the erosion of civilizations. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 9780520248700.

External links

- Texas A&M AgriLife Research and Extension Center at Lubbock; along with New Mexico University Extension Service. No-till and Cover Crops for Texas and New Mexico.

- No-Till Farmer Website