Nilotic peoples

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| Nile Valley, African Great Lakes, Lake Chad, southwestern Ethiopia | |

| Languages | |

| Nilotic languages | |

| Religion | |

| Traditional faiths (Dinka religion), Christianity |

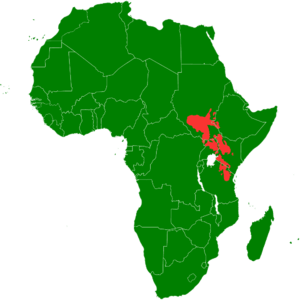

The Nilotic peoples are peoples indigenous to the Nile Valley who speak Nilotic languages, which constitute a large sub-group of the Nilo-Saharan languages spoken in South Sudan, Uganda, Kenya, and northern Tanzania.[1] In a more general sense, the Nilotic peoples include all descendants of the original Nilo-Saharan speakers. Among these are the Luo, Sara, Maasai, Kalenjin, Dinka, Nuer, Shilluk, Ateker, and the Maa-speaking peoples, each of which is a cluster of several ethnic groups.[2] Some ethnic groups in West Africa such as the Serer people of Senegal, the Gambia and Mauritania have been reported as being of Nilotic origin.[3][4]

The Nilotes constitute the majority of the population in South Sudan, an area that is believed to be their original point of dispersal. After the Bantu peoples, they constitute the second-most numerous group of peoples inhabiting the African Great Lakes region around the Eastern Great Rift.[2] They make up a notable part of the population of southwestern Ethiopia as well.

The Nilote peoples primarily adhere to Christianity and traditional faiths, including the Dinka religion.

Name

The terms Nilotic and Nilote were previously used as racial sub-classifications, based on anthropological observations of the distinct body morphology of many Nilotic speakers. Twentieth-century social scientists have largely discarded such efforts to classify peoples according to physical characteristics, in favor of using linguistic studies to distinguish among peoples. They formed ethnicities and cultures based on shared language.[5] Since the late 20th century, however, social and physical scientists are making use of data from population genetics.[6]

Nilotic and Nilote are now mainly used to classify "Nilotic people" based on ethnic identification and linguistic families. Etymologically, the terms Nilotic and Nilote (singular nilot) derive from the Nile Valley; specifically, the Upper Nile and its tributaries, where most Sudanese Nilo-Saharan-speaking people live.[7]

Ethnic/linguistic divisions

Languages

Linguistically, Nilotic people are divided into three sub-groups:

- Eastern Nilotic - Spoken by Nilotic populations in southwestern Ethiopia, eastern South Sudan, northeastern Uganda, western Kenya and northern Tanzania. Includes languages like Turkana and Maasai.

- Bari

- Teso–Lotuko–Maa

- Southern Nilotic - Spoken by Nilotic populations in western Kenya, northern Tanzania and eastern Uganda. Includes Kalenjin and Datog.

- Kalenjin

- Omotik–Datooga

- Western Nilotic - Spoken by Nilotic populations in South Sudan, Sudan, northeastern Congo (DRC), northern Uganda, southwestern Kenya, northern Tanzania and southwestern Ethiopia. Includes Dinka and Luo.

- Dinka–Nuer

- Luo

Ethnic groups

Nilotic people constitute the bulk of the population of South Sudan. The largest of the Sudanese Nilotic peoples are the Dinka, who have as many as twenty-five ethnic subdivisions. The next largest group are the Nuer, followed by the Shilluk.[8]

The Nilotic people in Uganda include the Luo (Acholi, Alur and Adhola), Ateker (Teso and Karamojong), Lango and Kumam.

In East Africa, the Nilotes are often subdivided into three general groups:

- The Plain Nilotes: they speak Maa languages and include the Maasai, Samburu and Turkana[2]

- The River Lake Nilotes: the Joluo (Kenyan Luo), who are part of the larger Luo group[2]

- The Highland Nilotes: subdivided into two groups, the Kalenjin and the Datog

Professor Cheikh Anta Diop posits that the Serer people who are found in Senegal, the Gambia and Mauritania are of Nilotic origin.[3][4] Physically, the Serer people have a strong resemblance to the Dinka (tall, dark and slender).

History

Origins

A Proto-Nilotic unity, separate from an earlier undifferentiated Eastern Sudanic unity, is assumed to have emerged by the 3rd millennium BC. The development of the Proto-Nilotes as a group may have been connected with their domestication of livestock. The Eastern Sudanic unity must have been considerably earlier still, perhaps around the 5th millennium BC (while the proposed Nilo-Saharan unity would date to the Upper Paleolithic about 15kya). The original locus of the early Nilotic speakers was presumably east of the Nile in what is now South Sudan. The Proto-Nilotes of the 3rd millennium BC were pastoralists, while their neighbors, the Proto-Central Sudanic peoples, were mostly agriculturalists.[10]

Early Expansion

Language evidence indicates an initial southward expansion out of the Nilotic nursery into far southern Sudan beginning in the second millennium B.C., the Southern Nilotic communities that participated in this expansion would eventually reach western Kenya between 1000 and 500 B.C.[11] Their arrival occurred shortly before the introduction of iron to East Africa.[12]

Expansion out of the Sudd

Linguistic evidence shows that over time Nilotic speakers, such as the Dinka, Shilluk, and Luo, took over. These groups spread from the Sudd marshlands, where archaeological evidence shows that a culture based on transhumant cattle raising had been present since 3000 BCE, and the Nilotic culture in that area may thus be continuous to that date.[13]

The Nilotic expansion from the Sudd Marshes into the rest of South Sudan seems to have begun in the 14th century. This coincides with the collapse of the Christian Nubian kingdoms of Makuria and Alodia and the penetration of Arab traders into central Sudan. From the Arabs the South Sudanese may have obtained new breeds of hump-less cattle.[13] Archaeologist Roland Oliver notes that the period also shows an Iron Age beginning among the Nilotics. These factors may explain how the Nilotic speakers expanded to dominate the region.

Shilluk

By the sixteenth century the most powerful group among the Nilotic speakers were the Cøllø (called Shilluk by Arabs and Europeans), who spread east to the banks of the white Nile under the legendary leadership of Nyikang, who is said to have ruled Läg Cøllø c.1490 to c.1517.[14] The Cøllø gained control of the west bank of the river as far north as Kosti in Sudan. There they established an economy based on cattle raising, cereal farming, and fishing, with small villages located along the length of the river.[15] The Cøllø developed an intensive system of agriculture, and the Cøllø lands in the 17th century had a population density similar to that of the Egyptian Nile lands.[16]

One theory is that it was pressure from the Cøllø that drove the Funj people north, who would establish the Sultanate of Sennar. The Dinka remained in the Sudd area, maintaining their transhumance economy.[17]

While the Dinka were protected and isolated from their neighbours, the Cøllø were more involved in international affairs. The Cøllø controlled the west bank of the White Nile, but the other side was controlled by the Funj Sultanate, and there were regular conflict between the two. The Cøllø had the ability to quickly raid outside areas by war canoe, and had control of the waters of the Nile. The Funj had a standing army of armoured cavalry, and this force allowed them to dominated the plains of the sahel.

Cøllø traditions tell of Rädh Odak Ocollo who ruled c. 1630 and led them in a three decade war with Sennar over control of the White Nile trade routes. The Cøllø allied with the Sultanate of Darfur and the Kingdom of Takali against the Funj, but the capitulation of Takali ended the war in the Funj's favour. In the later 17th century the Cøllø and Funj allied against the Jieng, a group of Dinka who rose to power in the border area between the Funj and Cøllø. The Cøllø political structure gradually centralized under the a king or reth. The most important is Rädh Tugø (son of Rädh Dhøköödhø) who ruled c. 1690 to 1710 and established the Cøllø capital of Fashoda. The same period saw the gradual collapse of the Funj sultanate, leaving the Cøllø in complete control of the White Nile and its trade routes. The Cøllø military power was based on control of the river.[18]

Azande

The non-Nilotic Azande people, who entered southern Sudan in the 16th century, established the region's largest state. The Azande are the third largest nationality in Southern Sudan. They are found in Maridi, Iba, Yambio, Nzara, Ezon, Tambura and Nagere Counties in the tropical rain forest belt of western Equatoria and Bahr el Ghazal. In the 18th century, the Avungara people entered and quickly imposed their authority over the Azande. Avungara power remained largely unchallenged until the arrival of the British at the end of the 19th century.[19]

Geographical barriers protected the southerners from Islam's advance, enabling them to retain their social and cultural heritage and their political and religious institutions. The Dinka people were especially secure in the Sudd marshlands, which protected them from outside interference, and allowed them to remain secure without a large armed forces. The Shilluk, Azande, and Bari people had more regular conflicts with neighbouring states

Culture and religion

Most Nilotes continue to practice pastoralism, migrating on a seasonal basis with their herds of livestock.[2] Some tribes are also known for a tradition of cattle raiding.[20]

Through lengthy interaction with neighbouring peoples, the Nilotes in East Africa have adopted many customs and practices from Southern Cushitic groups. The latter include the age set system of social organization, circumcision, and vocabulary terms.[2][21]

In terms of religious beliefs, Nilotes primarily adhere to traditional faiths and Christianity. The Dinka religion has a pantheon of deities. The Supreme, Creator God is Nhialic, who is the God of the sky and rain, and the ruler of all the spirits.[22] He is believed to be present in all of creation, and to control the destiny of every human, plant and animal on Earth. Nhialic is also known as Jaak, Juong or Dyokin by other Nilotic groups, such as the Nuer and Shilluk. Dengdit or Deng, is the sky God of rain and fertility, empowered by Nhialic.[23] Deng's mother is Abuk, the patron Goddess of gardening and all women, represented by a snake.[24] Garang, another deity, is believed or assumed by some Dinka to be a god suppressed by Deng; his spirits can cause most Dinka women, and some men, to scream. The term "Jok" refers to a group of ancestral spirits.

In the Lotuko mythology, the chief God is called Ajok. He is generally seen as kind and benevolent, but can be angered. He once reportedly answered a woman's prayer for the resurrection of her son. Her husband, however, was angry and killed the child. According to the Lotuko religion, Ajok was annoyed by the man's actions and swore never to resurrect any Lotuko again. As a result, death was said to have become permanent.

Genetics

Y DNA

A Y-chromosome study by Wood et al. (2005) tested various populations in Africa for paternal lineages, including 26 Maasai and 9 Luo from Kenya, and 9 Alur from the Democratic Republic of Congo. The signature Nilotic paternal marker Haplogroup A3b2 was observed in 27% of the Maasai, 22% of the Alur, and 11% of the Luo.[25]

According to Gomes et al. (2010),[26] Haplogroup B is another characteristically Nilotic paternal marker. It was found in 22% of Wood et al.'s Luo samples and 8% of the studied Maasai.[25] The E1b1b haplogroup has been observed at overall frequencies of around 11% among Nilo-Saharan-speaking groups in the Great Lakes area,[27] with this influence concentrated among the Maasai (50%).[25] This is indicative of substantial historic gene flow from Cushitic-speaking males into these Nilo-Saharan-speaking populations.[28] In addition, 67% of the Alur samples possessed the E2 haplogroup.[25]

A study by Hassan et al. (2008) analysed the Y-DNA of populations in the Sudan region, with various local Nilotic groups included for comparison. The researchers found the signature Nilotic A and B clades to be the most common paternal lineages amongst the Nilo-Saharan speakers, except those inhabiting western Sudan. There, a prominent North African influence was noted. Haplogroup A was observed amongst 62% of Dinka, 53.3% of Shilluk, 46.4% of Nuba, 33.3% of Nuer, 31.3% of Fur and 18.8% of Masalit. Haplogroup B was found in 50% of Nuer, 26.7% of Shilluk, 23% of Dinka, 14.3% of Nuba, 3.1% of Fur and 3.1% of Masalit. The E1b1b clade was also observed in 71.9% of the Masalit, 59.4% of the Fur, 39.3% of the Nuba, 20% of the Shilluk, 16.7% of the Nuer, and 15% of the Dinka.[29] Hassan et al. attributed the atypically high frequencies of the haplogroup in the Masalit to either a recent population bottleneck, which likely altered the community's original haplogroup diversity, or to geographical proximity to E1b1b's place of origin in North Africa. The researchers suggest that the clade "might have been brought to Sudan [...] after the progressive desertification of the Sahara around 6,000–8,000 years ago".[29] Henn et al. (2008) similarly observed Afro-Asiatic influence in the Nilotic Datog of northern Tanzania, 43% of whom carried the M293 sub-clade of E1b1b.[30]

mtDNA

Unlike the paternal DNA of Nilotes, the maternal lineages of Nilotes in general show low-to-negligible amounts of Afro-Asiatic and other extraneous influences. An mtDNA study by Castri et al. (2008) examined the maternal ancestry of various Nilotic populations in Kenya, with Turkana, Samburu, Maasai and Luo individuals sampled. The mtDNA of almost all of the tested Nilotes belonged to various Sub-Saharan macro-haplogroup L sub-clades, including L0, L2, L3, L4 and L5. Low levels of maternal gene flow from North Africa and the Horn of Africa were observed in a few groups, mainly via the presence of mtDNA haplogroup M and haplogroup I lineages in about 12.5% of the Maasai and 7% of the Samburu samples, respectively.[31]

Autosomal DNA

The autosomal DNA of Nilotic peoples has been examined in a comprehensive study by Tishkoff et al. (2009) on the genetic clusters of various populations in Africa. According to the researchers, Nilotes generally form their own African genetic cluster. The authors also found that certain Nilotic populations in the eastern Great Lakes region, such as the Maasai, showed some additional Afro-Asiatic affinities due to repeated assimilation of Cushitic-speaking peoples over the past 5000 or so years.[32]

Physiology

Physically, Nilotes are noted for their typically very dark skin color and slender, tall bodies. They often possess exceptionally long limbs, particularly vis-a-vis the distal segments (forearms, calves). This characteristic is thought to be a climatic adaptation to allow their bodies to shed heat more efficiently.

Sudanese Nilotes are regarded as one of the tallest peoples in the world. Roberts and Bainbridge (1963) reported average values of 182.6 cm (71.9") for height and 58.8 kg (129.6 lbs) for weight in a sample of Sudanese Shilluk.[33] Another sample of Sudanese Dinka had a stature/weight ratio of 181.9 cm/58.0 kg (71.6"/127.9 lbs), with an extremely ectomorphic somatotype of 1.6-3.5-6.2.

In terms of facial features, Hiernaux (1975) observed that the nasal profile most common amongst Nilotic populations is broad, with characteristically high index values ranging from 86.9 to 92.0. He also reported that lower nasal indices are often found amongst Nilotes who inhabit the more southerly Great Lakes region, such as the Maasai, a fact which he attributed to genetic differences.[34]

Additionally, it has been remarked that the Nilotic groups presently inhabiting the African Great Lakes region are sometimes smaller in stature than those residing in the Sudan region. Campbell et al. (2006) recorded measurements of 172.0 cm/53.6 kg (67.7"/118.2 lbs) in a sample of agricultural Turkana in northern Kenya, and of 174.9 cm/53.0 kg (68.8"/116.8 lbs) in pastoral Turkana.[35] Hiernaux similarly listed a height of 172.7 cm (68") for Maasai in southern Kenya, with an extreme trunk/leg length ratio of 47.7.[34]

Many Nilotic groups excel in long and middle distance running. Some researchers have suggested that this sporting prowess is related to their exceptional running economy, a function of slim body morphology and slender legs.[36] A study by Pitsiladis et al. (2006) surveyed 404 elite Kenyan distance runners; it found that 76% of the international-class respondents identified as part of the Kalenjin ethnic group and that 79% spoke a Nilotic language.[37]

References

- ↑ "Nilotic". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing. 2015. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Okoth, Assa; Ndaloh, Agumba (2006). Peak Revision K.C.P.E. Social Studies. Nairobi, Kenya: East African Educational Publishers. pp. 60–62. ISBN 978-9966-25-450-4. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- 1 2 Diop, Cheikh Anta, Antériorité Des Civilisations Nègres, L. Hill (1974), p. 198, ISBN 9781556520723

- 1 2 Diop, Cheikh Anta, « The African origin of civilization: myth or reality», (Ed. & tra. Mercer Cook), Lawrence Hill Book (1974), p. 198, ISBN 978-1-55652-072-3

- ↑ The Forging of Races Cambridge University Press THE FORGING OF RACES - by Colin Kidd Excerpt

- ↑ Sarah A. Tishkoff et al.: "The Genetic Structure and History of Africans and African Americans", Science (magazine)

- ↑ Article: "Nilot", Encyclopædia Britannica

- ↑ Helen Chapin Metz, ed. Sudan: A Country Study, Washington, DC: GPO for the Library of Congress, 1991.

- ↑ Oboler, Regina Smith (1985). Women, Power, and Economic Change: The Nandi of Kenya. Stanford University Press. p. 17. ISBN 0804712247.

- ↑ John Desmond Clark, From Hunters to Farmers: The Causes and Consequences of Food Production in Africa, University of California Press, 1984, p. 31

- ↑ Ehret, Christopher. An African Classical Age: Eastern & Southern Africa in World History 1000 B.C. to A.D.400. University of Virginia, 1998, p.7

- ↑ Clark, J., & Brandt, St, From Hunters to Farmers: The Causes and Consequences of Food Production in Africa. University of California Press, 1984, p.234

- 1 2 Robertshaw, Peter (1987). "Prehistory in the Upper Nile Basin". Journal of African History. 28 (2): 177–189. Retrieved 20 November 2017.

- ↑ Patricia Mercer. "Shilluk Trade and Politics from the Mid-Seventeenth Century to 1861." The Journal of African History 1971. Page 410 of 407-426

- ↑ "Shilluk." Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Africa and the Middle East, Volume 1 Infobase Publishing, 2009

- ↑ Nagendra Kr Singh. "International encyclopaedia of Islamic dynasties." Anmol Publications PVT. LTD., 2002 pg. 659

- ↑ "Dinka." Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Africa and the Middle East, Volume 1 Infobase Publishing, 2009

- ↑ Ogot, B. A., ed. (1999). "Chapter 7: The Sudan, 1500–1800". General History of Africa. Volume V: Africa from the Sixteenth to the Eighteenth Century. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. pp. 89–103. ISBN 978-0-520-06700-4.

- ↑ Metz, Helen Chapin, ed. Sudan: A Country Study. The Turkiyah, 1821-85 Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress, 1991.

- ↑ "South Sudan horror at deadly cattle vendetta". BBC News. 12 January 2012.

- ↑ Robert O. Collins, The Southern Sudan in Historical Perspective, (Transaction Publishers: 2006), p.9-10.

- ↑ Lienhardt, p 29

- ↑ Lienhardt, p 104

- ↑ Lienhardt, p 90

- 1 2 3 4 Elizabeth T Wood, Daryn A Stover, Christopher Ehret et al., "Contrasting patterns of Y chromosome and mtDNA variation in Africa: evidence for sex-biased demographic processes", European Journal of Human Genetics (2005) 13, 867–876. (cf. Appendix A: Y Chromosome Haplotype Frequencies)

- ↑ Gomes, V; Sánchez-Diz, P; Amorim, A; Carracedo, A; Gusmão, L (Mar 2010). "Digging deeper into East African human Y chromosome lineages". Hum Genet. 127 (5): 603–13. doi:10.1007/s00439-010-0808-5. PMID 20213473.

- ↑ Cruciani et al. (May 2004). "Phylogeographic Analysis of Haplogroup E3b (E-M215) Y Chromosomes Reveals Multiple Migratory Events Within and Out Of Africa" (PDF). American Journal of Human Genetics. 74 (5): 1014–1022. doi:10.1086/386294. PMC 1181964. PMID 15042509.

- ↑ Cruciani; et al. (May 2004). "Phylogeographic Analysis of Haplogroup E3b (E-M215) Y Chromosomes Reveals Multiple Migratory Events Within and Out Of Africa". Am J Hum Genet. 74 (5): 1014–1022. doi:10.1086/386294. PMC 1181964. PMID 15042509. Archived from the original on 2013-01-12.

- 1 2 Hassan, Hisham Y. et al. (2008), "Y-Chromosome Variation Among Sudanese: Restricted Gene Flow, Concordance With Language, Geography, and History," American Journal of Physical Anthropology (2008), Volume: 137, Issue: 3, Pages: 316-323

- ↑ Henn; Gignoux; Lin, Alice A; Oefner, Peter J. (2008), "Y-chromosomal evidence of a pastoralist migration through Tanzania to southern Africa", PNAS, 105 (31): 10693–10698, Bibcode:2008PNAS..10510693H, doi:10.1073/pnas.0801184105, PMC 2504844, PMID 18678889

- ↑ Castrí (2008). "Kenyan crossroads: migration and gene flow in six ethnic groups from Eastern Africa" (PDF). J Anthropol Sci. 86: 189–92. PMID 19934476.

- ↑ Tishkoff; et al. (2009), "The Genetic Structure and History of Africans and African Americans", Science, 324 (5930): 1035–44, Bibcode:2009Sci...324.1035T, doi:10.1126/science.1172257, PMC 2947357, PMID 19407144 ; Also see Supplementary Data

- ↑ D. F. Roberts, D. R. Bainbridge: "Nilotic physique," American Journal of Physical Anthropology (1963), p. 341-370

- 1 2 Jean Hiernaux, The People of Africa, (Scribners: 1975), pp.142-143 & 147.

- ↑ B. Campbell, P. Leslie, K. Campbell: "Age-related Changes in Testosterone and SHBG among Turkana Males." American Journal of Human Biology (2006), p. 71-82

- ↑ Bengt Saltin: "The Kenya project - Final report." New Studies In Athletics, vol. 2, pp. 15-24

- ↑ Yannis Pitsiladis, Vincent O. Onywera, Robert A. Scott, Michael K. Boit. "Demographic characteristics of elite Kenyan endurance runners" (PDF). Retrieved 20 June 2012.

Bibliography

- (in English) Lienhardt, Godfrey, Divinity and Experience: The Religion of the Dinka, Oxford University Press (1988), ISBN 0198234058 (Retrieved : 9 June 2012)