European New Zealanders

| Total population | |

|---|---|

|

2,969,391 (2013 census)[1] 74.02% of New Zealand's population | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| All regions of New Zealand | |

| Languages | |

| English | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Christianity (Anglicanism · Catholicism · Presbyterianism) | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| European Australians · British (English · Scottish · Welsh) · Irish · other European peoples |

European New Zealanders are New Zealanders of European descent.[2] Most European New Zealanders are of British and Irish ancestry, with smaller percentages of other European ancestries such as Croatians, Germans, Greeks, Poles (historically noted as German due to Partitions of Poland), French, Dutch, Scandinavians and South Slavs.[3] The term "European New Zealander" also includes white people who are of indirect European descent, such as Americans, Canadians, South Africans and Australians.[4]

Statistics New Zealand maintains the national classification standard for ethnicity. European is one of the six top-level ethnic groups, alongside Māori, Pacific Peoples, Asian, Middle Eastern/Latin American/African (MELAA), and Other. Within the top-level European group are two second-level ethnic groups, New Zealand European and Other European. New Zealand European consists of New Zealanders of European descent, while Other European consists of migrant European ethnic groups.[4] The term European New Zealander is therefore ambiguous, as it can refer to either the top-level European ethnic group or to the second-level New Zealand European group.

At the 2013 Census, 2,969,391 people (74%) identified as European, with 2,727,009 people (68%) identifying as New Zealand European.[1]

The Māori term Pākehā is often used as a synonym for European New Zealander.

History

Cook claimed New Zealand for Britain on his arrival in 1769. The establishment of British colonies in Australia from 1788 and the boom in whaling and sealing in the Southern Ocean brought many Europeans to the vicinity of New Zealand. Whalers and sealers were often itinerant and the first real settlers were missionaries and traders in the Bay of Islands area from 1809. Some of the early visitors stayed and lived with Māori tribes as Pākehā Māori. Often whalers and traders married Māori women of high status which served to cement trade and political alliances as well as bringing wealth and prestige to the tribe.[5] By 1830 there was a population of about 800 non Māori which included a total of about 200 runaway convicts and seamen. The seamen often lived in New Zealand for a short time before joining another ship a few months later. In 1839 there were 1100 Europeans living in the North Island. Violence against European shipping (mainly due to mutual cultural misunderstandings), the ongoing musket wars between Māori tribes (due to the recent relatively sudden introduction of firearms into the Maori world), cultural barriers and the lack of an established European law and order made settling in New Zealand a risky prospect. By the late 1830s the average missionary would tell you that many Māori were nominally Christian, many of the Māori slaves that had been captured during the Musket Wars had been freed and cannibalism had been largely stamped out. By this time, many Māori, especially in the north, could read and write Māori and to a lesser extent English.

1840 onwards

| Europe-born population of New Zealand 1851 - 2013 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | % of total overseas-born | (UK & Ireland) % of total overseas-born |

Ref(s) | ||

| 1851 | - | 100.0% | - | 84.4% | |

| 1858 | 36,443 | [7] | |||

| 1881 | 223,303 | 86.3% | [7] | ||

| 1961 | 265,660 | 227,459 | [8][9] | ||

| 1971 | 298,283 | 255,408 | [7] | ||

| 1981 | 298,251 | 257,589 | [7] | ||

| 1986 | 255,756 | 30.4% | [10] | ||

| 1991 | 285,555 | 239,157 | [10][7] | ||

| 1996 | 38.0% | ||||

| 2001 | 279,015 | 221,010 | [10][7] | ||

| 2006 | 251,688 | [11] | |||

| 2013 | 336,636 | 265,206 | 26.5% | [7] | |

European migration has resulted in a deep legacy being left on the social and political structures of New Zealand. Early visitors to New Zealand included whalers, sealers, missionaries, mariners, and merchants, attracted to natural resources in abundance. They came from the Australian colonies, Great Britain and Ireland, Germany (forming the next biggest immigrant group after the British and Irish),[12] France, Portugal, the Netherlands, Denmark, The United States, and Canada.

In 1840 representatives of the British Crown signed the Treaty of Waitangi with 240 Māori chiefs throughout New Zealand, motivated by plans for a French colony at Akaroa and land purchases by the New Zealand Company in 1839. British sovereignty was then proclaimed over New Zealand in May 1840. Some would later argue that the proclamation of sovereignty was in direct conflict with the treaty which in its Maori version had guaranteed sovereignty (Rangatiratanga) to the Maori who signed it.[13] By the end of the 1850s the European and Mäori populations were of a similar size as immigration and natural increase boosted European numbers.

Following the formalising of British sovereignty, the organised and structured flow of migrants from Great Britain and Ireland began. Government-chartered ships like the clipper Gananoque and the Glentanner carried immigrants to New Zealand. Typically clipper ships left British ports such as London and travelled south through the central Atlantic to about 43 degrees south to pick up the strong westerly winds that carried the clippers well south of South Africa and Australia. Ships would then head north once in the vicinity of New Zealand. The Glentanner migrant ship of 610 tonnes made two runs to New Zealand and several to Australia carrying 400 tonne of passengers and cargo. Travel time was about 3 to 3 1/2 months to New Zealand. Cargo carried on the Glentanner for New Zealand included coal, slate, lead sheet, wine, beer, cart components, salt, soap and passengers' personal goods. On the 1857 passage the ship carried 163 official passengers, most of them government assisted. On the return trip the ship carried a wool cargo worth 45,000 pounds.[14] In the 1860s discovery of gold started a gold rush in Otago. By 1860 more than 100,000 British and Irish settlers lived throughout New Zealand. The Otago Association actively recruited settlers from Scotland, creating a definite Scottish influence in that region, while the Canterbury Association recruited settlers from the south of England, creating a definite English influence over that region.[15] In the 1860s most migrants settled in the South Island due to gold discoveries and the availability of flat grass covered land for pastoral farming. The low number of Māori (about 2,000) and the absence of warfare gave the South Island many advantages. It was only when the New Zealand wars ended that The North Island again became an attractive destination.

In the 1870s the MP Julius Vogel borrowed millions of pounds from Britain to help fund capital development such as a nationwide rail system, lighthouses, ports and bridges, and encouraged mass migration from Britain. By 1870 the non-Māori population reached over 250,000.[16] Other smaller groups of settlers came from Germany, Scandinavia, and other parts of Europe as well as from China and India, but British and Irish settlers made up the vast majority, and did so for the next 150 years.

Demographics

| European population in New Zealand 1851 - 2013 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Population | Ref(s) | % of New Zealand | Year | Population | Ref(s) | % of New Zealand | |

| 1851 | 26,707 | [17] | - | 1966 | 2,426,352 | [8] | 90.6% | |

| 1881 | 489,933 | [17] | - | 1971 | 2,561,280 | [8] | 89.5% | |

| 1916 | 1,093,024 | [18] | 95.11% | 2001 | 2,871,432 | [19] | 80.06% | |

| 1921 | 1,209,243 | [18] | 95.1% | 2006 | 2,609,589 | [19] | 67.60% | |

| 1926 | 1,338,167 | [18] | 95.0% | 2013 | 2,969,391 | [19] | 74.02% | |

| 1936 | 1,484,508 | [20] | 94.33% | 2018 | ND> | [21] | ND | |

| 1945 | 1,592,908 | [20] | 93.6% | |||||

| 1951 | 1,809,441 | [20] | 93.3% | |||||

| 1956 | 2,016,287 | [20] | 92.7% | |||||

| 1961 | 2,216,886 | [8] | 91.8% | |||||

| Source: Statistics New Zealand. | ||||||||

The 2013 official census had 2,969,391 or 74.0% identify as European.[1] The general Census of New Zealand population was taken November- December 1851. Subsequent censuses were taken in 1858, 1861, 1864, 1867, 1871, 1874, 1878 and 1881 and thereafter at five-yearly intervals until 1926.[20] The table shows the ethnic composition of New Zealand population at each census since the early twentieth century. Europeans are still the largest ethnic group in New Zealand. Their proportion of the total New Zealand population has been decreasing gradually since the 1916 Census.[8]

The 2006 Census counted 2,609,592 European New Zealanders. Most census reports do not separate European New Zealanders from the broader European ethnic category, which was the largest broad ethnic category in the 2006 Census. Europeans comprised 67.6 percent of respondents in 2006 compared with 80.1 percent in the 2001 census.[22]

The apparent drop in this figure was due to Statistics New Zealand's acceptance of 'New Zealander' as a distinct response to the ethnicity question and their placement of it within the "Other" ethnic category, along with an email campaign asking people to give it as their ethnicity in the 2006 Census.[23]

In previous censuses, these responses were counted belonging to the European New Zealanders group,[24] and Statistics New Zealand plans to return to this approach for the 2011 Census.[25] Eleven percent of respondents identified as New Zealanders in the 2006 Census (or as something similar, e.g. "Kiwi"),[26] well above the trend observed in previous censuses, and higher than the percentage seen in other surveys that year.[27]

In April 2009, Statistics New Zealand announced a review of their official ethnicity standard, citing this debate as a reason,[28] and a draft report was released for public comment. In response, the New Zealand Herald opined that the decision to leave the question unchanged in 2011 and rely on public information efforts was "rather too hopeful", and advocated a return to something like the 1986 approach. This asked people which of several identities "apply to you", instead of the more recent question "What ethnic group do you belong to?"[29]

| Ethnicity | 2001 census | 2006 census | 2013 census |

|---|---|---|---|

| New Zealand European | 2,696,724 | 2,381,076 | 2,727,009 |

| English | 35,082 | 44,202 | 38,916 |

| British nfd | 16,572 | 27,192 | 36,024 |

| South African nec | 14,913 | 21,609 | 28,656 |

| Dutch | 27,507 | 28,644 | 28,503 |

| European nfd | 23,598 | 21,855 | 26,472 |

| Australian | 20,784 | 26,355 | 22,467 |

| Scottish | 13,782 | 15,039 | 14,412 |

| Irish | 11,706 | 12,651 | 14,193 |

| German | 9,057 | 10,917 | 12,810 |

| American | 8,472 | 10,806 | 12,339 |

| Russian | 3,141 | 4,836 | 5,979 |

| Canadian | 4,392 | 5,604 | 5,871 |

| French | 3,513 | 3,816 | 4,593 |

| Italian | 2,955 | 3,117 | 3,798 |

| Welsh | 3,414 | 3,774 | 3,708 |

| Croatian | 2,505 | 2,550 | 2,673 |

| European nec | 477 | 942 | 2,637 |

| Greek | 2,280 | 2,355 | 2,478 |

| Swiss | 2,346 | 2,313 | 2,388 |

| Polish | 1,956 | 1,965 | 2,163 |

| Spanish | 1,731 | 1,857 | 2,043 |

| Danish | 1,995 | 1,932 | 1,986 |

| Zimbabwean | N/A | 2,556 | 1,617 |

| Romanian | 522 | 1,554 | 1,452 |

| Swedish | 1,119 | 1,254 | 1,401 |

| Hungarian | 894 | 1,212 | 1,365 |

| Afrikaner | N/A | 1,341 | 1,197 |

| Czech | 600 | 756 | 1,083 |

| Serbian | 753 | 1,029 | 1,056 |

| Austrian | 891 | 993 | 1,029 |

| Other European | 9,906 | 9,669 | 9,207 |

| Total people, European | 2,871,432 | 2,609,589 | 2,969,391 |

- nfd - not further defined (insufficient data to classify the response further)

- nec - not elsewhere classified (no classification exists for the response)

Alternative terms

Pākehā

The term Pākehā, the etymology of which is unclear,[30] is used interchangeably with European New Zealanders. The 1996 census used the wording "New Zealand European (Pākehā)" in the ethnicity question, however the word Pākehā was subsequently removed after what Statistics New Zealand called a "significant adverse reaction" to its use to identify ethnicity.[31] In 2013, the New Zealand Attitudes and Values Study carried out by The University of Auckland found no evidence that the word was derogatory, 14% of the overall respondents to the survey chose the option Pākehā to describle themselves with the remainder preferring New Zealander, New Zealand European or simply Kiwi.[32][33]

Palagi

The term "Palagi", pronounced Palangi, is Samoan in origin and is used in similar ways to Pākehā, usually by people of Samoan or other Pacific Island descent.

British and Irish New Zealanders

For residents of citizens that originate from New Zealand see New Zealanders in the United Kingdom

- See also: British people, Irish people

The New Zealand 2006 census statistics reported citizens with British (27,192), English (44,202), Scottish (15,039), Irish (12,651), Welsh (3,771) and Celtic (1,506) origins. Historically, a sense of 'Britishness' has figured prominently in the identity of many New Zealanders.[34] As late as the 1950s it was common for New Zealanders to refer to themselves as British, such as when Prime Minister Keith Holyoake described Sir Edmund Hillary's successful ascent of Mt. Everest as "[putting] the British race and New Zealand on top of the world".[35] New Zealand passports described nationals as "British Subject and New Zealand Citizen" until 1974, when this was changed to "New Zealand Citizen".[36]

While "European" identity predominates political discourse in New Zealand today, the term "British" is still used by some New Zealanders to explain their ethnic origins. Others see the term as better describing previous generations; for instance, journalist Colin James referred to "we ex-British New Zealanders" in a 2005 speech.[37] It remains a relatively uncontroversial descriptor of ancestry.

Politics

Colonial period

As the earliest colonists of New Zealand, settlers from England and their descendants often held positions of power and made or helped make laws often because many had been involved in government back in England.

The Founding Fathers

The lineage of most of the Founding Fathers of New Zealand was British (especially English) such as:

- James Busby (from Scotland with English and Scottish parents) drafted the Declaration of the Independence of New Zealand and, with William Hobson, co-authored the Treaty of Waitangi.

- Captain William Hobson (from Waterford, Ireland) is the principal author of the Treaty of Waitangi and the first governor of New Zealand.

Various other founders of New Zealand have also been unofficially recognised:

- Captain James Cook, the Englishman who voyaged to, and claimed New Zealand for the crown

- Captain Arthur Phillip (Englishman), first governor of New South Wales, founder of the first colony with nominal authority over all of Australia east of the 135th meridian, including all of New Zealand bar the southern-most part of South Island.

- Sir George Grey (English and Irish parents), the third governor of New Zealand and the eleventh New Zealand Prime Minister.

- Henry Sewell (English parents), the first New Zealand Prime Minister.

Culture

European-New Zealand culture is the culture of New Zealand. The culture of New Zealand is essentially a Western culture influenced by the unique geography of New Zealand, the diverse input of Māori and other Oceanian people, the British colonisation of New Zealand that began in 1840, and the various waves of multi-ethnic migration that followed.[38] As the English were always the largest element among the settlers, their cultural influence was naturally greater than that of the Irish, Welsh or Scots. Evidence of a significant Anglo-Celtic heritage includes the predominance of the English language, the common law, the Westminster system of government, Christianity (Anglicanism) as the once dominant religion, and the popularity of sports such as rugby and cricket; all of which are part of the heritage that has shaped modern New Zealand.

European settlement increased through the early decades of the 19th century, with numerous trading stations established, especially in the North. The experiences of European New Zealanders have endured in New Zealand music, cinema and literature. Kerikeri, founded in 1822, and Bluff founded in 1823, both claim to be the oldest European settlements in New Zealand after the CMS mission station at Hohi, which was established in December 1814.

Language

New Zealand English is a major variety of the English language and is used throughout New Zealand. Having an official status in the Constitution, New Zealand English is the one of the country's official languages and is the first language of the majority of the population.

New Zealand English began to diverge from British English after the English language was established in New Zealand by colonists during the 19th century. It arose from the intermingling of early settlers from a great variety of mutually intelligible dialectal regions of the British Isles and quickly developed into a distinct variety of English. New Zealand English differs from other varieties of English in vocabulary, accent, pronunciation, register, grammar and spelling.

The earliest form of New Zealand English was first spoken by the children of the colonists born into the colony of New Zealand. This first generation of children created a new dialect that was to become the language of the nation. The New Zealand-born children in the new colony were exposed to a wide range of dialects from all over the British Isles, in particular from Ireland and South East England. The native-born children of the colony created the new dialect from the speech they heard around them, and with it expressed peer solidarity. Even when new settlers arrived, this new dialect was strong enough to blunt other patterns of speech. The most commonly spoken European languages other than English in New Zealand are French and German.

Music

Another area of cultural influence are New Zealand Patriotic songs:

- "God Defend New Zealand" is a national anthem of New Zealand - Created by the Irish-born composer Thomas Bracken, the song was first performed in 1876, and was sung in New Zealand as a patriotic song. It has equal status with "God Save the Queen" but "God Defend New Zealand" is more commonly used. It did not gain its status as an official anthem until 1977, following a petition to Parliament asking "God Defend New Zealand" to be made the national anthem in 1976.

- "God Save the Queen" - New Zealand's other official national anthem, and was the sole national anthem until 1977. "God Save the Queen" is also the national anthem of the United Kingdom and was adopted in 1745. It is now most often played only when the sovereign, Governor-General or other member of the Royal Family is present, or in other situations where a royal anthem would be used, or on some occasions such as Anzac Day.[39]

Architecture

Scottish architect Sir Basil Spence provided the original conceptual design of the Beehive in 1964. The detailed architectural design was undertaken by the New Zealand government architect Fergus Sheppard, and structural design of the building was undertaken by the Ministry of Works.[40] The Beehive was built in stages between 1969 and 1979.[41] W. M. Angus constructed the first stage - the podium, underground car park and basement for a national civil defence centre, and Gibson O'Connor constructed the ten floors of the remainder of the building.[42] Bellamy's restaurant moved into the building in the summer of 1975–76 and Queen Elizabeth II, Queen of New Zealand, unveiled a plaque in the reception hall in February 1977. The Prime Minister, Robert Muldoon, formally opened the building in May 1977. The government moved into the upper floors in 1979. The annex facing Museum Street was completed in 1981.[42] In July 2015, Heritage New Zealand declared the Beehive "of outstanding heritage significance for its central role in the governance of New Zealand".

Many of the more imposing structures in and around Dunedin and Christchurch were built in the latter part of the 19th century as a result of the economic boom following the Central Otago Gold Rush. A common style for these landmarks is the use of dark basalt blocks and facings of cream-coloured Oamaru stone, a form of limestone mined at Weston in North Otago. Notable buildings in this style include Dunedin Railway Station, the University of Otago Registry Building, Christchurch Arts Centre, Knox Church, Dunedin, ChristChurch Cathedral, Christchurch, Christ's College, Christchurch, Garrison Hall, Dunedin, parts of the Canterbury Provincial Council Buildings and Otago Boys' High School.

Place names in New Zealand of European origin

There are many places in New Zealand named after people and places in Europe, especially the United Kingdom, the Republic of Ireland, and the Netherlands as a result of the many English, Scottish, Welsh, Irish, Dutch and other European settlers and explorers. These include the name "New Zealand" itself, as described below, along with several notable cities and regions:

- New Zealand - In 1645 Dutch cartographers renamed the land Nova Zeelandia after the Dutch province of Zeeland.[43][44] British explorer James Cook subsequently anglicised the name to New Zealand.[lower-alpha 1]

- Auckland - Both the city and region, as well as the former province, are named after George Eden, Earl of Auckland, whose title comes from the town of West Auckland, Durham, in England

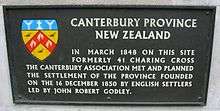

- Canterbury - the region, and former province, are named after Canterbury, England.

- Christchurch - the original name of the city, "Christ Church", was decided prior to the ships' arrival, at the Association's first meeting, on 27 March 1848. The exact basis for the name is not known. It has been suggested that it is named for Christchurch, in Dorset, England; for Canterbury Cathedral; or in honour of Christ Church, Oxford. The last explanation is the one generally accepted.[45]

- Dunedin - comes from Dùn Èideann, the Scottish Gaelic name for Edinburgh, the Scottish capital.

- New Plymouth - named for Plymouth, England

- Wellington - Both the city and region, as well as the former province, are named after Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington, whose title comes from the town of Wellington, Somerset, in England.

Small pockets of settlers from other European countries add to the identity and place names of specific New Zealand regions, most notably the Scandinavian-inspired place names of Dannevirke and Norsewood in southern Hawke's Bay.

Prime Ministers

All of the ancestors of the forty Prime Ministers of New Zealand were European and Anglo-Celtic (English, Scottish, Northern Irish, Welsh, or Irish). Some ancestors of three Prime Ministers did not emigrate from Britain or Ireland: some of the ancestors of David Lange were Germans, some of the ancestors of Julius Vogel were European Jews, and some of John Key's ancestors were Austrian migrants (his mother's side).

See also

Notes

References

- 1 2 3 4 "2013 Census – Major ethnic groups in New Zealand". stats.govt.nz. 29 January 2015. Retrieved 11 January 2016.

- ↑ Bruce Hill (8 February 2013). ""Pakeha" not a negative word for European New Zealanders". ABC Radio Australia. Retrieved 11 January 2016.

- ↑ Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand: New Zealand Peoples

- 1 2 "Classifications and related statistical standards – Ethnicity". Statistics New Zealand. June 2005. Retrieved 13 November 2016.

- ↑ "Kōrero: Intermarriage; Whārangi – Early intermarriage". Te Ara (The Encyclopedia of New Zealand). 13 July 2012. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- ↑ Patterson, Brad (2014). "'We love one country, one queen, one flag': Loyalism in Early Colonial New Zealand 1840-80". In Allan Blackstock; Frank O'Gorman. Loyalism and the Formation of the British World, 1775-1914. Boydell & Brewer Ltd. p. 244. ISBN 978-1-84383-912-5.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "New Zealanders of overseas birth, 1961–2013". Teara.gov.nz. 20 May 2015. Retrieved 25 December 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 1974 World Population Year: The Population of New Zealand (PDF). Committee for International Co-ordination of National Research in Demography (CICRED). 1974. p. 53. Retrieved 2 November 2017: TABLE 3.11: Total Population by Ethnic Origin, 1916-1971

- ↑ Ten most common birthplaces by country of birth 1961 Birthplaces of New Zealand's population 1858–2006

- 1 2 3 Bedford, Richard D.; Jacques Poot (2010). "New Zealand: Changing Tides in the South Pacific: Immigration to Aotearoa New Zealand". In Uma A. Segal; Doreen Elliott; Nazneen S. Mayadas. Immigration Worldwide: Policies, Practices, and Trends. Oxford University Press. p. 266. ISBN 978-0-19-974167-0. Retrieved 3 November 2017.

- ↑ "2013 Census QuickStats about culture and identity" (PDF). National Business Review Radio. Statistics New Zealand. 2013. Retrieved 11 January 2016.

- ↑ Germans: First Arrivals (from the Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand)

- ↑ "'Differences between the texts'". NZ History. Ministry for Culture and Heritage.

- ↑ Glentanner. B. Lansley. Dornie Publishing. Invercargill 2013.

- ↑ "History of Immigration – 1840 – 1852".

- ↑ "History of Immigration – 1853 – 1870".

- 1 2 Locating the English Diaspora, 1500-2010 edited by Tanja Bueltmann, David T. Gleeson, Don MacRaild

- 1 2 3 Historical and statistical survey (Page:18)

- 1 2 3 "Culture and identity: Ethnic identities in Canterbury Census 2001, 2006, 2013 Census". Environment Canterbury Regional Council. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015: see worksheets 1 and 2 for detailed report [XLS format]

- 1 2 3 4 5 Dominion Population Committee (Reports of the) (Mr. James Thorn, Chairman) Appendix to the Journals of the House of Representatives, 1946. 1946. p. 2. Retrieved 2 November 2017 – via National Library of New Zealand.

- ↑ The 2018 New Zealand Census Population and Dwellings

- ↑ Statistics New Zealand Highlights: Ethnic groups in New Zealand

- ↑ Middleton, Julie (1 March 2006). "Email urges 'New Zealander' for Census". New Zealand Herald. APN Holdings NZ Limited. Retrieved 3 October 2007.

- ↑ QuickStats About Culture and Identity: European, Statistics New Zealand.

- ↑ Statistics New Zealand. (2009). Draft report of a review of the official ethnicity statistical standard: proposals to address issues relating to the ‘New Zealander’ response. Wellington: Statistics New Zealand. ISBN 978-0-478-31583-7. Accessed 27 April 2009.

- ↑ "A New Zealander response and like responses such as 'Kiwi' or 'NZer' are coded to a separate category, 'New Zealander', at level four in the Other Ethnicity group." Classification and coding process, New Zealand Classification of Ethnicity 2005, Statistics New Zealand. Accessed 4 January 2008.

- ↑ "Who responded as 'New Zealander'?" (Press release). Statistics New Zealand. 3 August 2007. Archived from the original on 4 April 2008. Retrieved 3 October 2007.

- ↑ "Feedback sought on ethnicity statistics" (Press release). Statistics New Zealand. 27 April 2009. Retrieved 27 April 2009.

- ↑ "Editorial: A question to define who you are". The New Zealand Herald. 2 May 2009. Retrieved 30 October 2011.

- ↑ Jodie Ranford (24 September 1999). "Pakeha, its origin and meaning". Maorinews.com. Retrieved 25 December 2015.

- ↑ "Final Report Review Official Ethnicity Statistical Standard 2009" (PDF). stats.govt.nz. Statistics New Zealand. Retrieved 25 August 2015.

- ↑ "Pakeha not a dirty word - survey". 5 February 2013.

- ↑ "Research busts myth that "Pākehā" is a derogatory term". 5 February 2013.

- ↑ Te Ara: New Zealanders: New Zealand Peoples: Britons

- ↑ Population Conference 1997, New Zealand: Panel Discussion 3c - Population Change And International Linkages, Phillip Gibson, Chief Executive, Asia 2000 Foundation

- ↑ Carl Walrond. 'Kiwis overseas - Staying in Britain', Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand, updated 13 April 2007.

- ↑ The Pacific-ation of New Zealand. Colin James's speech to the Sydney Institute, 3 February 2005. Accessed 5 June 2007.

- ↑ Science Education in International Contexts,

New Zealand is a Western culture

- ↑ "National anthems: Protocols". Ministry for Culture and Heritage. 21 November 2014. Retrieved 15 August 2015.

- ↑ "Executive Wing (the Beehive)". Register of Historic Places. Heritage New Zealand. Retrieved 19 July 2015.

- ↑ "The Beehive – Executive Wing". New Zealand Parliament. 31 October 2006. Retrieved 25 January 2010.

- 1 2 Martin, John E. (28 March 2012). "History of Parliament's buildings and grounds". New Zealand Parliament. Retrieved 19 July 2015.

- ↑ Wilson, John (September 2007). "Tasman's achievement". Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 16 February 2008.

- ↑ Mackay, Duncan (1986). "The Search For The Southern Land". In Fraser, B. The New Zealand Book Of Events. Auckland: Reed Methuen. pp. 52–54.

- ↑ Cowie, D.J. (2 July 1934). "How Christchurch Got Its Name: A Controverted Subject". The New Zealand Railways Magazine. New Zealand Railways. 9 (4): 31. OCLC 52132159. Retrieved 4 March 2011.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to New Zealanders of European descent. |