Tottenham Hotspur Stadium

View of stadium under construction from the east | |

| Full name | Tottenham Hotspur Stadium |

|---|---|

| Location |

Tottenham London, N17 England |

| Coordinates | 51°36′17.1″N 0°03′59.1″W / 51.604750°N 0.066417°W |

| Public transit |

|

| Owner | Tottenham Hotspur |

| Operator | Tottenham Hotspur |

| Capacity | 62,062 (stadium)[1] |

| Field size | 105 by 68 metres (114.8 yd × 74.4 yd) |

| Surface |

Desso GrassMaster (football) Turf Nation (NFL)[2] |

| Construction | |

| Built | 2018 |

| Opened | late 2018 (planned) |

| Construction cost |

£350–400 million (stadium)[3] £850 million (entire project)[3] |

| Architect | Populous |

| General contractor | Mace |

Tottenham Hotspur Stadium is a stadium currently under construction that will serve as the home ground for Tottenham Hotspur in North London. It has a planned capacity of 62,062, one of the largest in the Premier League and the largest for a club stadium in London. It is designed to be a multi-purpose stadium and features the world-first dividing retractable football pitch that reveals a synthetic turf underneath for NFL London Games, concerts and other events. The club opted not to use the name of the previous stadium White Hart Lane, choosing to name it Tottenham Hotspur Stadium instead pending a naming rights deal.

The construction of the stadium was initiated as the centrepiece of the Northumberland Development Project, intended to be the catalyst for a 20-year regeneration project in Tottenham. The project covers the site of the now demolished ground of White Hart Lane and areas adjacent to it. The project was first conceived in 2007 and announced in 2008, but the plan was revised several times, and the construction of the stadium, beset by disputes and delays, did not commence until 2015. The stadium is due to be completed during the 2018–19 season. The stadium is scheduled to open with a ceremony before the first competitive game begins.

History

Early grounds

Tottenham Hotspur was formed in 1882, and the early matches of club were played on public land at Tottenham Marshes.[4] As the matches became more popular with the public and the number spectators increased, the club decided to move to an enclosed ground so as that it can charge entrance fee and control the crowd. In 1888, the club rented a pitch at Asplins Farm next to the railway line at Northumberland Park.[5] However, the ground became overcrowded, and in 1899, the club moved to a piece of land to the east of Tottenham High Road behind the White Hart pub owned by the brewery company Charringtons.[6] This would become the White Hart Lane ground.

The club acquired the freehold of the ground as well as additional land at the northern (Paxton Road) end in 1905.[7][8] Starting in 1909, a stadium with stands designed by Archibald Leitch was built over a period of two and a half decades. The stadium would have a capacity of nearly 80,000 by 1934. Over the years, the stadium underwent a number of changes, and seating replaced the standing areas, which reduced the capacity to about 50,000 in 1979. Significant standing areas, however, still existed, including the long stretch of raised standing terrace on the East Stand, known by fans as The Shelf.[9]

Beginning in the 1980s, the Tottenham home ground White Hart Lane was redeveloped, and in order to comply with the recommendation of the Taylor Report, it was turned into an all-seater stadium. The capacity of the stadium was reduced to around 36,000 by the time it was completed in 1998. The capacity was by then lower than other major English clubs with many of these clubs also planning to expand further. As revenues from gate receipts in that period formed a substantial part of the club's income (before it became dominated by TV broadcast rights deals),[10] Tottenham began to explore ways of increasing the stadium capacity so that it could more effectively compete financially with rival clubs.[11]

Over the years, a number of schemes were considered, such as rebuilding the East Stand as a three-tier structure, moving to a different stadium and locations including Picketts Lock and the Olympic Stadium at Stratford, London.[11] These plans however failed to come to fruition,[12][13] except for a proposal to redevelop the existing site that would become the Northumberland Development Project.[14]

Planning

The club first announced In 2007 that it was considering redevelopment of the current site as one of options under consideration.[15] In April 2008, the club revealed that it was considering the acquisition the Wingate industrial estate immediately adjacent to the north of White Hart Lane for the building a stadium.[16] In October 2008, the Northumberland Development Project that included the construction of a stadium, as well club museum, homes, shops and other facilities was announced.[17][18] The early plan was that Tottenham would move into the new stadium, while it was partially built, for the beginning of the 2012–13 season, and the stadium would be completed by the end of the following season. However, the project would be delayed, with the plan undergoing a few revision and the completion date pushed back several times.[19][20] The club also did not fully commit itself to building the stadium in Tottenham until January 2012 after it had lost its bid to use the Olympic Stadium to West Ham United.[14]

The first plan of the project with a 58,000-capacity stadium was released in April 2009 for public consultation.[21] In October 2009, the planning application for a 56,000-seat stadium designed by KSS Design Group and other buildings was then submitted.[22][23] However, the proposal included the demolition of eight locally listed buildings and two nationally listed buildings, which was criticised by conservation groups including English Heritage as well as the Government's advisory body on architecture, the Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment.[24][25][26] In response to the objections, a revised plan that retained some of the listed buildings was resubumited in May 2010.[27][28] This plan was accepted by Haringey Council on 30 September 2010, later the Mayor of London Boris Johnson as well as the government.[29][30][31] However, only part of this plan, the construction of Lilywhite House, would be implemented.[32]

In August 2011, a major riot erupted in a deprived area of Tottenham. Haringey Council, keen to keep the economically-important club within the community, granted planning permission for the project on 20 September 2011,[3][33][34] and a week later relieved the club of all community infrastructure payments normally required for such project.[35] In a joint statement with Haringey Council in January 2012, Tottenham announced that it would stay in North Tottenham and work with the council to rejuvenate the area.[36] In this scheme, the Northumberland Development Project would serve as the catalyst for a 20-year regeneration program planned by the Haringey Council.[37][38][39] In March 2012, Haringey Council approved of plans to hand over council-owned land in the redevelopment area, including part of Wingate Trading Estate as well as Paxton Road and Bill Nicholson Way, to Spurs. It also agreed on a Compulsory Purchase Order (CPO) to buy the remaining properties on Paxton Road that had yet to sell.[40][41] After a long delay, the Secretary of State for the Department for Communities and Local Government Eric Pickles, confirmed the CPO on 11 July 2014.[42][43] The owner of the remaining business with two plots on the development site, Archway Sheet Metal Works, then attempted but failed to have the CPO decision quashed in the High Court.[44] On 31 March 2015, the remaining plots on the Paxton Road were acquired, allowing the development to proceed.[45][46]

In October 2013, it was revealed that the club was considering a new plan for a multi-use stadium that may host American NFL games.[47] On 8 July 2015, it was announced that the club had reached an agreement with NFL to hold a minimum of two NFL games a year in a 10-year partnership.[48] The same day a new design team was also announced alongside a revised project plan with Populous responsible for the stadium design.[38] In December 2015, the revised plans were approved by Haringey Council, including the demolition of locally listed buildings.[49][50] The Mayor of London Boris Johnson also gave formal approval of the plan in February 2016.[51]

Construction

The construction for the Northumberland Development Project started in September 2012, however, the construction of the stadium itself did not commence until 2015 due to the CPO dispute. The stadium was constructed in two main phases so that White Hart Lane can still be used in the 2016–17 season while the construction was in progress. The first phase involved the construction of the northern section of the stadium (including the North, West and East Stands), while the South Stand construction would start in the second phase after White Hart Lane had been demolished. Large part the land north of the existing stadium had been cleared by 2014 while the CPO dispute was ongoing.[52] After the dispute was resolved, preliminary work on the basement began in the summer of 2015,[53] with concrete and ground works for the foundation by the subcontractor Morrisroe starting in autumn 2015 based on earlier approved and amended plans.[54][55][56]

The new plan for the project was given final approval in February 2016, which allowed the construction of the main structure of the new stadium itself to start soon after. In order to facilitate the construction of northern section of the stadium while matches of the final season were still being played at the Lane, the northeast corner of White Hart Lane was demolished in the summer of 2016 after the 2015–16 season.[57][58] From the basement to level 6, the construction of this section is in reinforced concrete.[59] Three further levels above are constructed in steel frame. There are only six cores in reinforced concrete for vertical circulation of spectators instead of the eight expected of a stadium of this size as they needed to be constructed within the first phase of the stadium construction.[60] The South Stand constructed in the second phase would have open staircases to the concourses.[61]

The demolition of the entire White Hart Lane began immediately after the last home match of the 2016–17 season was played, with the demolition completed in August 2017.[62] Piling work for Phase 2 of the stadium construction started in June 2017.[63] While the northern section constructed in the first phase is a largely concrete structure, the entire single-tier south stand has a steel frame to allow for a speedier construction.[60] The two steel "trees" that support the south stand were erected in December 2017.[64]

Parts of the old White Hart Lane were incorporated into the new stadium – crushed aggregate of the concrete foundation of White Hart Lane was mixed in with new concrete to create the floor of the concourse of the new stadium,[65] and bricks from the East Stand were used for the Shelf Bar.[66] The pitch was laid in early October 2018.[67]

Opening

The club initially announced that it would hold four test events at the stadium in August and early September 2018.[68] The first two events would be attended only by club staff, the following two would be the first open to the public with increasing levels of attendances and are necessary for the issuing of safety certificate.[69] The two games would be an Academy game and a legends match between Tottenham Hotspur and Bayern Munich, but these were postponed.[70][71]

For the early stages of the 2018–19 season, Tottenham will play at least their first four Premier League and all their Champions League group stage home games at Wembley Stadium.[72] They also played their home game in the round 3 of the EFL Cup at Stadium MK .[73] The opening was originally planned for the second home match against Liverpool in September,[74][75] but issues with the critical safety systems due to faulty electrical wiring delayed the opening of the stadium.[76][77] An opening ceremony will take place before the first game.[3] The first NFL game was due to be Oakland Raiders against Seattle Seahawks on 14 October 2018 but this too was relocated to Wembley following the stadium delay.[76][78]

Architecture and facilities

The stadium is an enclosed asymmetric bowl with a capacity of 62,062. The bowl shape of the stadium comes from the need to maximise hospitality facilities while the asymmetry is the result of the creation of a single-tier stand in the south.[79] The stadium is around 48m high, 250m long on its north-south axis and about 200m wide east to west.[80] There are 9 floors in the northern section above the basement and 5 floors in the south, with a gross internal area of 119,945 m2.[80] The front of the West Stand faces the High Road and features a projecting angled glazed box that encases an escalator and serves as the main entrance for guests. The projecting entrance along with the facades of other buildings of the Tottenham Experience present a traditional linear frontage along the High Road. A 9.5m pavement is created in front of these buildings to improve the flow of the crowd on match day on the High Road. To the east on Worcester Avenue is a dedicated entrance for NFL.[61] There are two raised podiums, one to the north and one to the south, for fans access. A large open public square the size of Trafalgar Square has been created on the south podium as the main access point for home fans, and it may be used for sporting and community activities.[81] Away fans may enter from the northeast corner of the stadium via the north podium. The South Stand features a 5-storey atrium with a single 7,000 m2 curved glazed facade.[82]

The bulk of the structure dominates the surrounding area, but the appearance of the mass of the building is modulated by different cladding of glass, metal panels and pre-cast concrete. The perforated metal panels work as a screen for the plant areas in the stadium that also allow for natural ventilation and light, and act a unifying element in the appearance of the stadium. Regions of glazing are not covered by the metal screen, including the main entrances and concourses, offices, Sky Lounge as well the extensive glazed area to the south, allow for views into and out of the stadium.[82] The metal panels may open and close and change character in different lighting conditions, and they are lined with LED luminaires that glow on match nights similar to Bayern Munich's Allianz Arena.[83]

The roof is a cable net structure held in place by an elliptically-shaped compression ring.[84] The roof is clad in standing seam aluminium panels that end with extruded polycarbonate on the inside edge to allow light through onto the pitch but reduce the contrast of the shadow of the roof on the pitch.[82] Curved alumininum eave cassettes connect the roof to the wall. The pitch will be lit by 324 LED floodlights arranged in 54 groups of six placed on columns of the roofing system.[85] Four LED screens are placed in the stadium, the two on the south side are the largest of any stadium in Western Europe.[86] There are also two facade video displays on the outside of the stadium and three tiers of LED ribbon displays inside.[87][88]

The stadium is designed with good acoustics in mind so as to optimise the atmosphere on match day. The corners of the stadium are closed, the stands are placed close to the pitch with fans generating a "wall of sound" that can reverberate around the ground.[89][90]

Stands

Although the stadium is a bowl, it will have four distinct stands. The South Stand is designated the 'Home End', and it has a single tier which is the largest single-tier stand in the country with seating for 17,500 fans. The design of the South Stand was influenced by Borussia Dortmund's Signal Iduna Park and is intended to be the "heart-beat" of the stadium that can generate an intense atmosphere on match day.[91][92][82] The North Stand has three tiers, the East and West Stands have four tiers each, two of which are smaller and are intended for premium seating. There are around 7,000 of these premium seats as well as private loges and super loges for premium members and corporate hospitality.[93] The total of 62,062 seats are mostly in navy blue,[94] with 42,000 of these intended for season ticket holders.[95] The seats have a minimum width of 470mm compared with the 455–460mm of the previous stadium, and raised to 520–700mm for premium seats. Away fans are allocated seats in the north east corner; 3,000 seats in the lower tier for Premier League games, while for domestic cups they may be allocated up to 15% of the capacity spread over three tiers.[96] The stands also include areas with 7,500 seats that could be quickly turned into safe standing areas should there be a change in the legislation that banned standing in football stadiums.[97][98] A family area is located in the north west corner for those attending with their children. For disabled fans, accessible seating is available in all four stands, where the design allows for flexible seating for family groups.[99]

Pitch

The football pitch of the stadium has a standard dimension of 105m x 68m, which is 440 square metres larger than the pitch at White Hart Lane.[100] The overall grass surface is 114.58m x 79.84m including the perimeter between the pitch and the stands. The stands are placed closed to the pitch so as to enhance the atmosphere on match days, and the distances between the stands and the pitch minimised – 7.97 metres (26.1 ft) from the front of the stand to the pitch on the west, north and east sides of the pitch and 4.985 metres (16.4 ft) at the south end of the pitch.[101]

In order to keep the football pitch in optimum condition, there are two different surfaces – a Desso GrassMaster hybrid grass pitch for football, and a synthetic turf surface underneath to be used for NFL games as well as concerts and other events.[101][81] The football pitch can be retracted in a way similar to that of Arizona Cardinals's home stadium, but it is the first in the world to split into three sections before retracting.[102][103] Each of the three sections weighs more than 3,000 tonnes, and is made up of 33 smaller trays, making a total of 99 trays with a combined weight of 10,000 tonnes.[104] The retracting pitch slides under the South Stand and the south podium, and the surface can be switched in around 25 minutes. The NFL pitch is placed 1.5m beneath the natural turf surface, and the change in height when the surface is switched also produces the ideal sightlines for the front row for both codes.[105]

The stadium features the world's first integrated pitch grow lighting system with grow lights suspended on six 70-metre trusses to encourage the growth of the grass in the shaded areas of the stadium, and they can be folded away under the North Stand when not in used.[106][107][67] The grass can also be maintained with artificial lighting and irrigation system when the pitch is retracted under the south podium.[108]

Facilities

The stadium provides separate facilities for football and NFL players, including media and medical facilities. There are a number of bars for fans on match day. In the South Stand is the Goal Line Bar, which at 65m is the longest in Europe. The White Hart and The Shelf are bars in the East Stand, while The Dispensary is found in the West Stand.[109] Also in the South Stand is the 'Market Place' with 60 food and drink outlets open, and a selection of food outlets also available in other stands.[110] Other features includes an in-house bakery and the world's first micro brewery in a stadium, which can produce one million pints of craft beer a year and deliver up to 10,000 pints a minute.[111][112] Some car parking, but not for general admission fans, is provided underneath the stand and in the basement. A range of hospitality facilities in the east and west stands are provided for those with premium memberships, including two Sky Lounges on the top floor of the East and West Stands with views over London and the pitch, the Sky Bridge which is the world's first bridge to be suspended from the roof of a stadium, 65 suites of private loges and super loges, and the "Tunnel Club" that allows its members observe the players as they walk from the dressing room to the pitch through a glass-walled tunnel.[113][114]

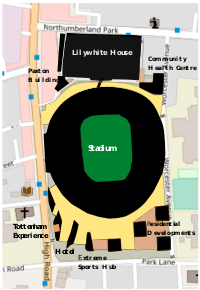

The stadium is intended to be active all year round as a sports and entertainment destination with conference and banqueting facilities. It offers visitor attractions such as a Sky Walk whereby visitors may walk up the side of stadium right up to the roof of the stadium, and it has a viewing deck over the South Stand where they may view the goal line from the roof or abseil down to the south podium.[81][82] The East Stand includes a double-height banquet hall that may be used for conference events.[81] To the south of the stadium, the raised podium forms a large open public square that may be used for a range of sporting and community activities. The Tottenham Experience, which include a club shop and a museum on Tottenham High Road, serves as the arrivals hub for visitors where they may collect tickets and start a tour of the stadium. The museum is located in the Grade II listed Warmington House, and the new club shop is the largest in Europe and features a 100-seat auditorium area that may be used for pre-match experiences.[115] Other facilities are offered in ancillary buildings surrounding the stadium, including an extreme sports building, a community health centre, and a ticket office.[81]

Statuary

A near-double-sized replica of the spurs cockerel, originally created in 1909 and once sat atop the east stand at White Hart Lane, will be placed on the roof structure above the South Stand.[116] A number of statues of significant figures of the club will be placed around the stadium. The statue of Bill Nicholson will be placed on the south west approach to the stadium; the old gate to the West Stand from White Hart Lane it will also be placed here, and the statue of Nicholson will be positioned at the centre of gate, recreating a historic photographic image of Nicholson.[117]

Uses

The stadium is intended to be used for a number of purposes and will serve as the venue for association football as well as NFL games and other events. It will host up to 16 non-football events a year, two of which are NFL games, and up to 6 music concerts.[118]

Cost, finance and sponsorship

The construction of the stadium itself is projected to cost £350–400 million, out of the estimated £850 million cost for the entire Northumberland Development Project.[3] An early estimate put Phase 2 of the development that includes the construction of the stadium at 305 million,[119] however the cost had increased due to the higher cost of import caused by the Brexit vote on the exchange rate, changes to the build, overtime working, extra hirings and higher construction cost.[120][121]

A £200m interim financing facility was arranged in December 2015 with three banks to finance the project.[122] This was replaced in May 2017 by a £400 million five-year loan deal with the banks to fund the remaining built.[123] By this stage, £340 million had already been spent on land acquisition, the planning process as well as construction cost; £100 million of this came from the 2015 interim financing, with the rest from the club resources.[124] The NFL contributed £10 million to allow at least two NFL games per year in the stadium.[125]

Partnership and deals

The club has a number of partners at the stadium. Following on tradition Heineken who have previous sponsored Tottenham have been named as the beer sponsor for the new stadium.[126] The north London brewer Beavertown is the official craft beer supplier and it installed the world's first stadium-located microbrewery on the south east corner of the stadium.[127] The company selected by the club to supply the advertising system in the new ground will be TGI.[128] Tottenham signed a contract with LG to supply the new stadium with Ultra-premium TVs and digital signage.[129] Hewlett-Packard is the IT networking and wireless infrastructure partner for the new stadium.[130]

Naming rights

The stadium is named Tottenham Hotspur Stadium until a naming-rights agreement is reached.[131] The club is reported to be looking for deals worth £20m annually (£400 million a 20-year deal worth or £200 million for ten years).[132][133]

Transport

The stadium is accessible via a number of London Overground, London Underground and National Rail stations: Seven Sisters, Tottenham Hale, Northumberland Park, and White Hart Lane stations. The nearest station at around 200m away is White Hart Lane which is being rebuilt, and a Wembley-style walkway for fans from the station to the stadium is planned. The stadium area is also served by up to 144 buses an hour.[134] Bus routes that stop close to the ground are 149, 259, 279, 349, and W3.[135] The club will also operate two high frequency shuttle bus services to the stadium, one from Alexandra Palace via Wood Green, and the other from Tottenham Hale.[134]

References

- ↑ "Spurs stadium capacity increased to 62,062". Sky Sports. 5 March 2018. Retrieved 6 March 2018.

- ↑ "Turf Nation". Stadia.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Kilpatrick, Dan (30 July 2018). "New Tottenham stadium 'not possible' without 2011 London riots". The Evening Standard.

- ↑ Goodwin, Bob (2007). Tottenham Hotspur: The Complete Record (2 ed.). Derby Books. ISBN 978-1-85983-846-4.

- ↑ Martin Cloake, Alan Fisher (15 August 2016). "Chapter 2: Enclosure Changed the Game Forever". People's History of Tottenham Hotspur: How Spurs Fans Shaped the Identity of One of the World's Most Famous Clubs. Pitch Publishing.

- ↑ Cloake, Martin (13 May 2017). White Hart Lane has seen Diego Maradona and Johan Cruyff, but after 118 years Tottenham have outgrown it. The Independent.

- ↑ "Northumberland Development Project, Tottenham". Haringey Council. October 2009.

- ↑ "History of White Hart Lane". Tottenham Hotspur.

- ↑ Evans, Tony (13 May 2017). "The Shelf at Tottenham once made White Hart Lane London's most hostile stadium". Evening Standard.

- ↑ Wilson, Bill. "Premier League finances enter new era, says Deloitte". BBC.

- 1 2 "Proposed New East Stand Redevelopment for Tottenham Hotspur Football Club" (PDF). Spurs Since 1882. June 2001.

- ↑ Simons, Raoul (30 July 2003). "Spurs plan down the Tube". Evening Standard.

- ↑ West Ham chosen as preferred Olympic Stadium tenant BBC Sport online Retrieved 12 February 2011

- 1 2 Collett, Mike (31 January 2012). "Spurs commit to new stadium in Tottenham". Reuters.

- ↑ "Stadium Update". Tottenhamhotspur.com. 6 May 2008. Archived from the original on 9 May 2008. Retrieved 25 May 2008.

- ↑ Hytner, David (9 April 2008). "Spurs consider White Hart Lane exit for 55,000-seat stadium". The Guardian.

- ↑ "Tottenham Hotspur Confirms Northumberland Development Project". Tottenham Hotspur. 30 October 2008.

- ↑ "Spurs reveal images of new ground". BBC Sport. 15 December 2008. Retrieved 16 December 2008.

- ↑ "Tottenham Hotspur stadium plan drops hotel for college and more flats". Tottenahm and Wood Green Journal. 25 January 2012. Archived from the original on 21 February 2015. Retrieved 29 May 2013.

- ↑ "Tottenham stadium delay means club face season away from home BBC Sport website 10 December 2014". BBC. Retrieved 20 February 2015.

- ↑ Bright, Richard (1 April 2009). "Tottenham's new stadium could have an ice rink". The Telegraph.

- ↑ Sheringham, Sam (26 October 2009). "Spurs aim for new stadium by 2012". BBC.

- ↑ Richardson, Sarah (18 November 2008). "Make and KSS to design Spurs stadium". Building.

- ↑ Allen, Felix (20 May 2010). "Spurs try again as £400m stadium plan is ruled offside". Evening Standard.

- ↑ "Tottenham's plans to redevelop White Hart Lane shown red card". Times online. Archived from the original on 28 May 2010. Retrieved 22 May 2010.

- ↑ "15 historic buildings set for demolition under Spurs stadium plans". SAVE Britain Heritage.

- ↑ Thomas, Lyall (2 October 2014). "Premier League: Tottenham press ahead with stadium plans". Sky Sports.

- ↑ Ley, John (20 May 2010). "Tottenham redesign new stadium to preserve listed buildings". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 15 June 2018.

- ↑ "Tottenham given go ahead to redevelop White Hart Lane by Mayor of London Boris Johnson". The Telegraph. 25 November 2010.

- ↑ "Stadium Plans". THFC Official website. Archived from the original on 3 October 2010. Retrieved 15 June 2018.

- ↑ "New Stadium Plans Update". Tottenham Hotspur. 9 December 2010.

- ↑ "Club Annoucement". 16 February 2015.

- ↑ "Northumberland Development Project Update". Tottenhamhotspur.com. Archived from the original on 24 November 2011. Retrieved 20 September 2011.

- ↑ "Tottenham sign planning agreement to build new stadium". BBC. 20 September 2011.

- ↑ "Club reveal next stage plans for Northumberland Development Tottenham stadium: Club offered White Hart Lane deal". BBC. 28 September 2011. Retrieved 18 November 2011.

- ↑ Thain, Bruce (31 January 2012). "Spurs confirm intention to stay in Tottenham and help rejuvenate the area". Enfield Independent.

- ↑ "A Plan Tottenham" (PDF). Haringey Council. 2012.

- 1 2 "Project Update". THFC. Archived from the original on 14 July 2015. Retrieved 12 July 2015.

- ↑ Bevan, Robert (25 March 2014). "Tottenham in £1 billion turnaround". London Evening Standard.

- ↑ Lamden, Tim (March 29, 2012). "Spurs granted right to remove final business in the way of new ground". Tottenham and Wood Green Journal. Archived from the original on 15 February 2013.

- ↑ Bryan A. (29 March 2012). "Another Obstacle Between Tottenham Hotspur and Their New Stadium Falls". Cartilage Free Captain.

- ↑ "New Tottenham Hotspur stadium scheme gets the green light". Department for Communities and Local Government. 11 July 2014. Retrieved 12 July 2014.

- ↑ "Northumberland Development Project - CPO Confirmed". Tottenham Hotspur. 11 July 2014. Retrieved 12 July 2014.

- ↑ "Tottenham plans for new stadium given massive boost as business looking to block move loses High Court appeal". Daily Telegraph. 20 February 2015. Retrieved 20 February 2015.

- ↑ "Joint Statement". Tottenham Hotspur Football Club. 31 March 2015. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- ↑ "Chairman'S Message". Tottenham Hotspur Football Club. 16 May 2015.

- ↑ Waite, Richard (24 October 2013). "Tottenham Hotspurs' secret plans for White Hart Lane mega stadium". The Architects' Journal.

- ↑ Wilson, Jeremy (8 Jul 2015). "Tottenham sign deal with NFL to stage American Football matches at new 61,000-seater stadium". The Telegraph.

- ↑ "Tottenham Hotspur Football Club Stadium Development". Haringey London.

- ↑ Tottenham's revised stadium plans approved by Haringey Council BBC News. Retrieved 17 December 2015

- ↑ Long, Sam (25 February 2016). "New Tottenham stadium: Mayor of London Boris Johnson gives formal approval to Spurs redevelopment". Evening Standard.

- ↑ "Football news in brief". The Guardian. 13 July 2014.

- ↑ "Project Update". Tottenham Hotspur. Archived from the original on 14 July 2015.

- ↑ "Final go-ahead for £400m Spurs stadium". Construction Enquirer. 25 February 2016.

- ↑ "Tottenham Hotspur Football Stadium". Morrisroe.

- ↑ "Online Planning Services". Haringey London.

- ↑ Menno, Dustin (6 May 2016). "Tottenham Hotspur confirms upcoming partial demolition of White Hart Lane stand". Cartilage Free Captain.

- ↑ "Stadium Construction Update - Latest Aerial Photos". Tottenham Hotspur. 17 August 2016.

- ↑ "Environmental Statement". Haringey Council. September 2015.

- 1 2 Jones, Tom (17 May 2017). "Home Sweet Home: Tottenham Hotspur's last match at White Hart Lane". Populous.

- 1 2 "Tottenham Hotspur Design and Access Statement 2015: 7.1 Stadium Design Concept". Haringey Council.

- ↑ "Tottenham's redevelopment of White Hart Lane gathers pace as last visual part of ground is removed". Daily Mail. 31 July 2017. Retrieved 7 August 2017.

- ↑ "Spurs Stadium Project" (PDF), Tottenham Hotspur Supporters' Trust

- ↑ Hein, Thomas (11 November 2017). "Tottenham Deploy 'Trees' In New £850m Stadium To Take The Weight Of The South Stand Which Will Be The Largest In Europe".

- ↑ Prior, Grant (8 March 2018). "White Hart Lane crushed aggies form new Spurs stadium floors". Construction Enquirer.

- ↑ "New stadium - latest photos - Shelf Bar and LED". Tottenham Hotspur. 19 April 2018.

- 1 2 Ouzia, Malik. "New Tottenham stadium: Pitch is laid as Spurs unveil 'world-first' technology". The Evening Standard.

- ↑ de Menezes, Jack (14 June 2018). "Tottenham announce stay at Wembley Stadium and reveal first game at new White Hart Lane against Liverpool". The Independent. Retrieved 17 June 2018.

- ↑ Menno, Dustin (24 July 2018). "Tottenham confirm two test events ahead of new stadium opening". Cartilage Free Captain. Retrieved 11 October 2018.

- ↑ "Spurs announce Test Events for new stadium". Sky Sports. 24 July 2018. Retrieved 24 July 2018.

- ↑ Neil, Alex (1 September 2018). "(Gallery) Spurs release new photos of the stadium". Spurs Web. Retrieved 3 September 2018.

- ↑ Kilpatrick, Dan. "Tottenham confirm Wembley date for Manchester City match and stadium will stage Champions League group stage". Evening Standard.

- ↑ "Tottenham given permission to move Watford Carabao Cup tie to Milton Keynes". Sky Sports. 5 September 2018.

- ↑ "Premier League fixtures 2018-19: Man City visit Arsenal on opening weekend". BBC Sport. 14 June 2018. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

- ↑ "Tottenham: Liverpool the visitors for first game at new stadium". BBC Sport. 14 June 2018. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

- 1 2 Wilson, Jeremy (13 August 2018). "Tottenham forced to delay opening of new stadium until end of October after 'issues with critical safety systems". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 14 August 2018.

- ↑ "Tottenham stadium delay down to 'faulty wiring', says Mace". Sky Sports. 23 August 2018. Retrieved 24 August 2018.

- ↑ "Raiders face Seahawks in first game at new Tottenham stadium". Reuters. 12 January 2018. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

- ↑ "Tottenham Hotspur Design and Access Statement 2015: Design Response". Haringey Council. Retrieved 27 July 2018.

- 1 2 "Tottenham Hotspur Design and Access Statement 2015: Overview". Haringey Council. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Tottenham Hotspur Football Club". Populous.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Tottenham Hotspur Design and Access Statement 2015: Part 7.5". Haringey Council Services.

- ↑ Gold, Alasdair (24 April 2018). "Spurs unveil impressive feature that will transform the outside of their new £850m stadium". football.london. Retrieved 6 July 2018.

- ↑ "New Stadium Update: Commencement of Roof Lift". Tottenham Hotspur. 8 February 2018.

- ↑ "Pitch lights will be LED, says Spurs". LUX. 6 March 2018. Retrieved 12 July 2018.

- ↑ Gold, Alasdair (17 May 2018). "New Spurs stadium: Latest photos, video and completion date as we walk around site". football.london.

- ↑ "Tottenham Hotspur Selects Daktronics To Provide LED Video Displays For New Stadium". Daktronics.

- ↑ "Daktronics to supply LED displays for new Tottenham stadium". TheStadiumBusiness. 27 March 2018.

- ↑ Dutton, Tom (29 December 2016). "Tottenham's new stadium will have better atmosphere than Arsenal's Emirates, says Spurs director Donna-Maria Cullen". Evening Standard.

- ↑ Megson, Kim (20 January 2017). "White Hart Lane: Populous MD lifts the lid on the design of Tottenham's community-driven new stadium". Clad News.

- ↑ "Behind the Design: The Single-Tier Stand to Drive Atmosphere of Tottenham Hotspur's New South Stand". Populous. 21 December 2017.

- ↑ McGurk, Stuart (23 January 2017). "Spurs stadium designers: "We've built it like a concert hall"". GQ.

- ↑ "New Spurs stadium: tunnel views at eyewatering prices". The Week. 20 January 2017. Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- ↑ "Tottenham's new stadium to have 15,000 seats ripped out after building blunder". talkSPORT. 27 June 2018.

- ↑ "Welcome Home - Secure Your Seat and 'Look Around' the New Stadium". Tottenham Hotspur Football Club.

- ↑ Gold, Alasdair (19 April 2017). "Seven key answers about Spurs' new stadium including if White Hart Lane's cockerels will be saved". football.london.

- ↑ Dean, Sam (26 June 2018). "Tottenham's new stadium has been 'future-proofed' for safe standing". Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 6 July 2018.

- ↑ Ziegler, Martyn (27 July 2018). "Tottenham Hotspur can convert to safe-standing within an hour". The Times. Retrieved 27 July 2018.

- ↑ "Welcome Home - Secure Your Seat and 'Look Around' the New Stadium". Tottenham Hotspur Football Club. 12 March 2018. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- ↑ Smith, Adam (16 August 2017). "Will the bigger Wembley pitch affect Tottenham this season?". Sky Sports.

- 1 2 "Tottenham Hotspur Design and Access Statement 2015". Haringey Council.

- ↑ Young, Alex (7 September 2017). "Tottenham give impressive first look at 'world-first dividing retractable pitch' for new stadium". Evening Standard.

- ↑ "Tottenham Hotspur will have world's first dividing retractable pitch, so they can host football and NFL". The Daily Telegraph. 7 September 2017.

- ↑ Prior, Grant (26 January 2018). "Installation work starts on Spurs retractable pitch". Construction Enquirer.

- ↑ Hastings, Rob (24 January 2017). "Spurs are starting a stadium design revolution in Tottenham". iNews. Retrieved 20 July 2018.

- ↑ Conway, Richard (26 September 2018). "Spurs' new stadium 'will be greatest ever built' says chief engineer". BBC Sport.

- ↑ Gold, Alasdair (9 September 2018). "Revealed: What the new metal structures fans have spotted at Spurs' new stadium are for". football.london.

- ↑ Edwards, David (3 June 2016). "Architect Christopher Lee from Populous talks modern stadium design". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 12 July 2018.

- ↑ "Our Feature Bars". Tottenham Hotspur Football Club. Retrieved 12 July 2018.

- ↑ "Levy UK and Tottenham Hotspur announces winning food and drink offering for new stadium". Compass. 21 June 2018. Retrieved 12 July 2018.

- ↑ Burt, Jason (20 January 2017). "Tottenham give taster of new stadium... with its own micro brewery". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 8 July 2018.

- ↑ "Beavertown to open Microbrewery at Club's new stadium". Tottenham Hotspur. 30 May 2018. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- ↑ Blunden, Mark (20 January 2017). "New Tottenham stadium: Tunnel Club, Michelin-calibre food and even a micro-brewery - The premium side of Tottenham's new stadium". Evening Standard. Retrieved 11 July 2018.

- ↑ "Details of new Spurs stadium's £20m roof emerge with luxury restaurant that will 'hang from it' Alasdair GoldTottenham Hotspur". football.london. 26 June 2017. Retrieved 12 July 2018.

- ↑ "Tottenham Experience". iSpurs. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- ↑ Gold, Alasdair (10 September 2018). "Tottenham are adding something classy to their new stadium and the fans are going to love it". football.london.

- ↑ "A fitting place for Bill in new stadium plans". Tottenham Hotspur Football Club. Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- ↑ Kilpatrick, Dan (20 January 2017). "Tottenham want Premier League's best atmosphere in building new stadium". ESPN. Retrieved 8 July 2018.

- ↑ "Project Appraisal From - Stage 2: Investment Decision". London.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 2 September 2012.

- ↑ Collomosse, Tom (8 March 2017). "New Tottenham Stadium: Tottenham reveal cost of new ground has risen to £800 million". Evening Standard.

- ↑ Prior, Grant (16 August 2018). "Spurs stadium builders "earning more than the players"". Construction Enquirer. Retrieved 21 August 2018.

- ↑ "Spurs secure £400m bank loan to complete £740m stadium build". Inside Football World. 1 June 2017.

- ↑ Collomosse, Tom (31 May 2017). "New Tottenham stadium: Spurs announce £400million loan deal to help finance new stadium". Evening Standard.

- ↑ Reilly, Alasdair (31 May 2017). "LPC-Tottenham Hotspur nets £400m stadium loan". Reuters.

- ↑ Dan Kilpatrick (21 April 2017). "NFL helping fund new Tottenham Hotspur stadium - sources". ESPN. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ↑ "Heineken named as official beer partner for Tottenham Hotspur's Iconic new stadium". Tottenham Hotspur Football Club. 18 May 2018. Archived from the original on 16 June 2018. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

- ↑ Powell, Tom (30 May 2018). "Tottenham Hotspur team up with Beavertown to create world's first microbrewery in a football stadium". Evening Standard.

- ↑ "TGI to deliver perimeter advertising system at club's new world-class stadium". Tottenham Hotspur Football Club. 31 May 2018. Retrieved 4 June 2018.

- ↑ "LG Chosen to Supply Ultra-Premium TVS and Digital Signage across new stadium". Tottenham Hotspur Football Club. 1 June 2018. Retrieved 4 June 2018.

- ↑ "Hewlett Packard Enterprise to support technology vision for new vision". Tottenham Hotspur Football Club. 11 July 2018. Retrieved 1 August 2018.

- ↑ Collomosse, Tom (27 February 2018). "New Tottenham stadium will be called the 'Tottenham Hotspur Stadium' if club starts season without naming-rights deal". London Evening Standard. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

- ↑ Luckings, Steve (3 May 2018). "The penny finally drops as Tottenham deal with spiralling costs of move back to White Hart Lane". The National. Retrieved 14 July 2018.

- ↑ Morgan, Tom (30 August 2018). "Tottenham Hotspur struggle for £200m naming deal for new stadium". The Daily Telegraph.

- 1 2 "Transport". Tottenham Hotspur.

- ↑ "How to get to White Hart Lane Stadium in Tottenham by Bus, Tube or National Rail". Moovit.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tottenham Hotspur Stadium. |