Native American use of fire

Native American tribes used fire to modify their landscapes in many significant ways prior to the arrival of European settlers.[1] Purposefully set fires by natives helped promote the valued resources and habitats that sustained indigenous cultures, economies, traditions, and livelihoods.[2] The cumulative ecological impacts of Native American fire use over time has resulted in a mosaic of grasslands and forests across North America that was once widely perceived as untouched, pristine wilderness.[3][4][5] It is now recognized that the original American landscape was already humanized at the time that the first European explorers, trappers, and settlers arrived; but the extent to which Native Americans manipulated entire ecosystems using fire remains a contentious topic.[6][7]

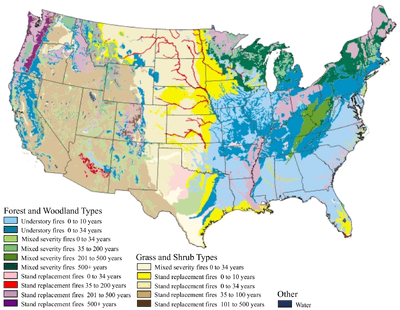

Changes in American Indian burning practices occurred as Europeans settled across the continent.[8] Some saw the potential benefits of low intensity, broadcast burns ("Indian-type" fires), while others feared and suppressed them.[8] In the 1880's, impacts of colonization had devastated indigenous populations, and fire exclusion became more widespread; by the early 20th century fire suppression had become official U.S. federal policy.[9] Understanding how Native Americans used fire pre-settlement provides an important basis for studying and reconstructing subsequent fire regimes throughout the landscape and is critical to correctly interpreting the ecological basis for vegetation distribution.[10][11][12][13]

Human-shaped landscape

Romantic and primitivist writers such as William Henry Hudson, Longfellow, Francis Parkman, and Thoreau contributed to the widespread myth[14] that pre-Columbian North America was a pristine, natural wilderness, "a world of barely perceptible human disturbance.”[15] At the time of these writings, however, enormous tracts of land had already been allowed to succeed to climax due to the reduction in anthropogenic fires after the native population collapsed from epidemics of diseases introduced by Europeans in the 16th century. In fact, Native Americans had played a major role in determining the diversity of their ecosystems.[16][14]

Fire scientists and ecologists are able to trace fire scars back hundreds of years using tree-ring analysis. Geographers studying lake sediments often find evidence of charcoal layers going back thousands of years, attributing the data to prehistoric lightning-caused fires. Early researchers did not believe that large burning was carried out by natives, but research during the latter half of the 20th century showed that many of the fires were intentionally caused.

The most significant type of environmental change brought about by Precolumbian human activity was the modification of vegetation. […] Vegetation was primarily altered by the clearing of forest and by intentional burning. Natural fires certainly occurred but varied in frequency and strength in different habitats. Anthropogenic fires, for which there is ample documentation, tended to be more frequent but weaker, with a different seasonality than natural fires, and thus had a different type of influence on vegetation. The result of clearing and burning was, in many regions, the conversion of forest to grassland, savanna, scrub, open woodland, and forest with grassy openings. (William M. Denevan)[17]

Fire was used to keep large areas of forest and mountains free of undergrowth for hunting or travel, or to create berry patches.[18][16][19] Intentional burning greatly modified landscapes across the continent in many subtle ways that were often interpreted as natural by the early explorers, trappers, and settlers.

Role of fire by natives

When first encountered by Europeans, many ecosystems were the result of repeated fires every one to three years, resulting in the replacement of forests with grassland or savanna, or opening up the forest by removing undergrowth. More forest exists today in some parts of North America than when the Europeans first arrived. In South America, the cerrado of South America has been coexisting with fire since ancient times; initially as natural fires caused by lightning alone, but later, also by fires caused by man. Terra preta soils, created by slow burning, are found mainly in the Amazon basin, where estimates of the area covered range from 0.1 to 0.3%, or 6,300 to 18,900 km² of low forested Amazonia to 1.0% or more (twice the surface of Great-Britain).[20][21][22]

There is some argument about the effect of human-caused burning when compared to lightning in western North America. There is agreement that natives played a significant role across the eastern part of that continent. As Emily Russell (1983) has pointed out, “There is no strong evidence that Indians purposely burned large areas....The presence of Indians did, however, undoubtedly increase the frequency of fires above the low numbers caused by lightning.” As might be expected, Indian fire use had its greatest impact “in local areas near Indian habitations.”[23][24]

Generally, the American Indians burned parts of the ecosystems in which they lived to promote a diversity of habitats, especially increasing the "edge effect," which gave the Indians greater security and stability to their lives.

Most primary or secondary accounts relate to the purposeful burning to establish or keep "mosaics, resource diversity, environmental stability, predictability, and the maintenance of ecotones." These purposeful fires by almost every Native American tribe differ from natural fires by the seasonality of burning, frequency of burning certain areas, and the intensity of the fire. Indians tended to burn differently depending on the resources being managed. Hardly ever did the various tribes purposely burn when the forests were most vulnerable to catastrophic wildfire. Indeed, for some Indians, saving the forest from fire was crucial for survival. Those Indian tribes that used fire in moist ecosystems tended to burn in the late spring just before new growth appears, while in areas that are drier fires tended to be set during the late summer or early fall since the main growth of plants and grasses occurs in the winter. For the most part, tribes set fires that did not destroy entire forests or ecosystems, were relatively easy to control, and stimulated new plant growth. Indians burned selected areas yearly, every other year, or intervals as long as five years.[18][16]

Reasons for burning

Henry T. Lewis concluded that there were at least 70 different reasons for the Indians firing the vegetation. Other writers have listed fewer number of reasons, using different categories. In summary, there are eleven major reasons for American Indian ecosystem burning:[18][16][19][25]

| Hunting | The burning of large areas was useful to divert big game (deer, elk, bison) into small unburned areas for easier hunting and provide open prairies/meadows (rather than brush and tall trees) where animals (including ducks and geese) like to dine on fresh, new grass sprouts. Fire was also used to drive game into impoundments, narrow chutes, into rivers or lakes, or over cliffs where the animals could be killed easily. Some tribes used a surround or circle fire to force rabbits and game into small areas. The Seminoles even practiced hunting alligators with fire. Torches were used to spot deer and attract fish. Smoke was used to drive/dislodge raccoons and bears from hiding. |

| Crop management | Burning was used to harvest crops, especially tarweed, yucca, greens, and grass seed collection. In addition, fire was used to prevent abandoned fields from growing over and to clear areas for planting corn and tobacco. One report of fire being used to bring rain (overcome drought). Clearing ground of grass and brush was done to facilitate the gathering of acorns. Fire was used to roast mescall and obtain salt from grasses. |

| Insect collection | Some tribes used a "fire surround" to collect and roast crickets, grasshoppers, Pandora Pinemoths in pine forests, and collect honey from bees. |

| Pest management | Burning was sometimes used to reduce insects (black flies, ticks, and mosquitos) and rodents, as well as kill mistletoe that invaded mesquite and oak trees and kill the tree moss favored by deer (thus forcing them to the valleys). Fire was also used to kill poisonous snakes. |

| Improve growth and yields | Fire was often used to improve grass for big game grazing (deer, elk, antelope, bison), horse pasturage, camas reproduction, seed plants, berry plants (especially raspberries, strawberries and huckleberries), and tobacco. Fire was also used to promote plant structure and health, increase the growth of reeds and grasses used as basket materials, beargrass, deergrass, hazel, and willows. |

| Fireproofing areas | There are some indications that fire was used to protect certain medicine plants by clearing an area around the plants, as well as to fireproof areas, especially around settlements, from destructive wildfires. Fire was also used to keep prairies open from encroaching shrubs and trees. |

| Warfare and signaling | Indians used fire to deprive the enemy of hiding places in tall grass and underbrush, to destroy enemy property, and to camouflage an escape. Large fires (not the Hollywood version of blankets and smoke) were ignited to signal enemy movements and to gather forces for combat. |

| Economic extortion | Some tribes also used fire for a "scorched earth" policy to deprive settlers and fur traders from easy access to big game and thus benefiting from being "middlemen" in supplying pemmican and jerky. |

| Clearing areas for travel | Fire was used to fell trees by boring two intersecting holes into the trunk, then dropping burning charcoal in one hole, allowing the smoke to exit from the other. This method was also used by early settlers. Another way to kill trees was to surround the base with fire, allowing the bark and/or the trunk to burn causing the tree to die (much like girdling) and eventually topple over. Fire also used to kill trees so that it could later be used for dry kindling (willows) and firewood (aspen). |

| Felling trees | Fire was used to fell trees by boring two intersecting holes into the trunk, then dropping burning charcoal in one hole, allowing the smoke to exit from the other. This method was also used by early settlers. Another way to kill trees was to surround the base with fire, allowing the bark and/or the trunk to burn causing the tree to die (much like girdling) and eventually topple over. Fire also used to kill trees so that it could later be used for dry kindling (willows) and firewood (aspen). |

| Clearing riparian areas | Fire was commonly used to clear brush from riparian areas and marshes for new grasses and sedges, plant growth (cattails), and tree sprouts (to benefit beaver, muskrats, moose, and waterfowl), including mesquite, cottonwood, and willows. |

Impacts of European settlement

By the time that European explorers first arrived in North America, millions of acres of "natural" landscapes were already manipulated and maintained for human use.[3][4][5] Fires indicated the presence of humans to many European explorers and settlers arriving on ship. In San Pedro Bay in 1542, chaparral fires provided that signal to Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo, and later to others across all of what would be named California.[26]

In the American west, it is estimated that 184,737 hectares (465,495 aces) burned annually pre-settlement in what is now Oregon and Washington.[27] The abundance of open prairie areas, which could be millions of acres large, was often incorrectly thought to be the result of poor soils that would not support trees or even crops. However, a number of settlers/farmers saw that the prairies were potentially rich land (besides the fact that it was "ready for the plow" without having to clear the land). This grass-covered prairie land was one of the primary reasons for settlers to head west to the Oregon Territory and California, and later to homestead the Great Plains.

By the 17th century, native populations were on the verge of collapse due to the introduction of diseases (such as smallpox) and widespread epidemics (the flu) against which the Indians had no immunity. Competition over land and resources resulted in warfare and shifts in local economies (i.e. fur trading, logging, overgrazing). Since the uplands were still in government ownership (public domain), many settlers adjacent to the hills often either deliberately set fires and/or allowed fires to "run free." Also, sheep and cattle owners, as well as shepherds and cowboys, often set the alpine meadows and prairies on fire at the end of the grazing season to burn the dried grasses, reduce brush, and kill young trees, as well as encourage the growth of new grasses for the following summer and fall grazing season.[16] Changes in management regimes had subsequent changes in American Indian diets, along with the introduction of alcohol has also had profound negative effects on indigenous communities. As Native populations dwindled, so did traditional management practices.[28]

By the 19th century, many native tribes has been forced to sign treaties with the federal government and relocate to reservations,[29] which were sometimes hundreds of miles away from their ancestral homelands. A handful of Indian sympathizers (mainly ethnographers and anthropologists employed by museums and universities) felt the need to record Indian languages and lifestyles before they presumably disappeared altogether. Even fewer of these researchers asked questions about the native peoples deliberately changing ecosystems.[16]

Through the turn of the 20th century, settlers continued to use fire to clear the land of brush and trees in order to make new farm land for crops and new pastures for grazing animals – the North American variation of slash and burn technology – while others deliberately burned to reduce the threat of major fires – the so‑called "light burning" technique. Light burning is also been called "Paiute forestry," a direct but derogatory reference to southwestern tribal burning habits.[30] The ecological impacts of settler fires were vastly different than those of their Native American predecessors. Natural (lightning-caused) fires also differed in location, seasonality, frequency, and intensity that Indian-set fires.[30]

Altered fire regimes

Removal of aboriginal populations and their fire have resulted in major ecological transformations.[29] Attitudes towards Indian-type burning have shifted in recent times, and many foresters and ecologists are now using prescribed fires to reduce fuel accumulations, change species composition, and manage vegetation structure and density for healthier forests and rangelands.[29] Some fire researchers and managers argue that adopting more Indian-type burning practices may prove ineffective for a variety of reasons ranging from insufficient data on the effectiveness of Indian burning, to difficulties in agreeing on a "natural" ecological baseline for restoration efforts.[29] Furthermore, tribal agencies and organizations have also begun to use traditional fire knowledge and practices in a modern context by reintroducing fire to fire-adapted ecosystems, on and adjacent to, tribal lands.[31][29]

See also

Further reading

- Blackburn, Thomas C. and Kat Anderson (eds.). 1993. Before the Wilderness: Environmental Management by Native Californians. Menlo Park, CA: Ballena Press. Several chapters on Indian use of fire, one by Henry T. Lewis as well as his final “In Retrospect.”

- Bonnicksen, Thomas M. 2000. America’s Ancient Forests: From the Ice Age to the Age of Discovery. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Especially see chapter 7 “Fire Masters” pages 143-216.

- Boyd, Robert T. (ed.). 1999. Indians, Fire, and the Land in the Pacific Northwest. Corvallis, OR: Oregon State University Press, ISBN 978-0-87071-459-7. An excellent series of papers about Indian burning in the West.

- Lewis, Henry T. 1982. A Time for Burning. Occasional Publication No. 17. Edmonton, Alberta: University of Alberta, Boreal Institute for Northern Studies. 62 pages.

- Lutz, Harold J. 1959. Aboriginal Man and White Men as Historical Causes of Fires in the Boreal Forest, with Particular Reference to Alaska. Yale School of Forestry Bulletin No. 65. New Haven, CT: Yale University. 49 pages.

- Pyne, Stephen J. 1982. Fire in America: A Cultural History of Wildland and Rural Fire. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. 654 pages. See Chapter 2 “The Fire from Asia” pages 66–122.

- Russell, Emily W.B. 1983. "Indian‑Set Fires in the Forests of the Northeastern United States." Ecology, Vol. 64, #1 (Feb): 78‑88.l

- Stewart, Omer C. with Henry T. Lewis and of course M. Kat Anderson (eds.). 2002. Forgotten Fires: Native Americans and the Transient Wilderness. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. 364 pages.

- Vale, Thomas R. (ed.). 2002. Fire, Native Peoples, and the Natural Landscape. Washington, DC: Island Press. An interesting set of articles that generally depict landscape changes as natural events rather that Indian caused.

- Whitney, Gordon G. 1994. From Coastal Wilderness to Fruited Plain: A History of Environmental Change in Temperate North America 1500 to the Present. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. See especially Chapter 5 “Preservers of the Ecological Balance Wheel” on pages 98–120.

References

- ↑ Stewart, O.C. (2002). Forgotten fires: Native Americans and the transient wilderness. OK, USA: Univ. of Oklahoma Press. p. 364. ISBN 978-0806140377.

- ↑ Lake, F. K., Wright, V., Morgan, P., McFadzen, M., McWethy D., Stevens-Rumann, C. (2017). "Returning Fire to the Land: Celebrating Traditional Knowledge and Fire" (PDF). Journal of Forestry. 115 (5): 343–353.

- 1 2 Arno & Allison-Bunnel, Stephen & Steven (2002). Flames in Our Forest. Island Press. p. 40. ISBN 1-55963-882-6.

- 1 2 Anderson & Moratto, M.K, and M.J. (1996). Native American land-use practices and ecological impacts. University of California, Davis: Sierra Nevada Ecosystem Project: Final Report to Congress. pp. 187–206.

- 1 2 Vale, Thomas (2002). Fire, Native Peoples, and the Natural Landscape. United States: Island Press. pp. 1–40. ISBN 155963-889-3.

- ↑ Pyne, S.J. (1995). World fire: The culture of fire on Earth. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press.

- ↑ Hudson, M. (2011). Fire Management in the American West. Boulder, CO: University Press of Colorado.

- 1 2 Weir, John (2009). Conducting Prescribed Burns: a comprehensive manual. Texas, U.S.A.: Texas A&M University Press College Station. pp. 1–12. ISBN 978-1-60344-134-6.

- ↑ Brown, Hutch (2004). "Reports of American Indian Fire Use in the East". Fire Management Today. 64 (3): 17–23.

- ↑ Barrett, S.W. (Summer 2004). "Altered Fire Intervals and Fire Cycles in the Northern Rockies". Fire Management Today. 64 (3): 25–29.

- ↑ Agee, J.K. (1993). Fire ecology of the Pacific Northwest forests. Washington, DC: Island Press.

- ↑ Brown, J.K. (2000). "Introduction and fire regimes". Wildland fire in ecosystems: Effects of fire on flora. 2: 1–7.

- ↑ Keeley, Jon (Summer 2004). "American Indian Influence on Fire Regimes in California's Coastal Ranges". Fire Management Today. 64 (3): 15–22.

- 1 2 Denevan, William M. (1992). "The Pristine Myth: The Landscape of the Americas in 1492". Annals of the Association of American Geographers. Washington, D.C.: Association of American Geographers. 82 (3): 369–385. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8306.1992.tb01965.x. ISSN 0004-5608.

- ↑ Shetler, Stanwyn G. (1991). "Faces of Eden". In Herman J. Viola and Carolyn Margolis. Seeds of Change: A Quincentennial Commemoration. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press. p. 226. ISBN 1-56098-036-2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Williams, Gerald W. "REFERENCES ON THE AMERICAN INDIAN USE OF FIRE IN ECOSYSTEMS". USDA Forest Service. Retrieved 2008-08-24.

- ↑ David L. Lentz, ed. (2000). Imperfect balance: landscape transformations in the Precolumbian Americas. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. xviii–xix. ISBN 0-231-11157-6.

- 1 2 3 Williams, Gerald W. (Summer 2000). "Introduction to Aboriginal Fire Use in North America" (PDF). Fire Management Today. USDA Forest Service. 60 (3): 8–12. Retrieved 2008-08-24.

- 1 2 Chapeskie, Andrew (1999). "Northern Homelands, Northern Frontier: Linking Culture and Economic Security in Contemporary Livelihoods in Boreal and Cold Temperate Forest Communities in Northern Canada". Forest Communities in the Third Millennium: Linking Research, Business, and Policy Toward a Sustainable Non-Timber Forest Product Sector. USDA Forest Service. pp. 31–44. Retrieved 2009-08-01.

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-08-20. Retrieved 2008-05-01. “Discovery and awareness of anthropogenic amazonian dark earths (terra preta)”, by William M. Denevan, University of Wisconsin–Madison, and William I. Woods, Southern Illinois University, Edwardsville. "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on August 20, 2008. Retrieved 2008-05-01.

- ↑ “Classification of Amazonian Dark Earths and other Ancient Anthropic Soils” in “Amazonian Dark Earths: origin, properties, and management” by J. Lehmann, N. Kaampf, W.I. Woods, W. Sombroek, D.C. Kern, T.J.F. Cunha et al., Chapter 5, 2003. (eds J. Lehmann, D. Kern, B. Glaser & W. Woods); cited in Lehmann et al.., 2003, pp. 77-102

- ↑ "Carbon negative energy to reverse global warming".

- ↑ Keeley, J. E.; Aplet, G.H.; Christensen, N.L.; Conard, S.C.; Johnson, E.A.; Omi, P.N.; Peterson, D.L.; Swetnam, T.W. Ecological foundations for fire management in North American forest and shrubland ecosystems. Gen. Tech. Rep. PNW-GTR-779. Portland, OR: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station. p. 33.

- ↑ Barrett, Stephen W.; Thomas W. Swetnam; William L. Baker (2005). "Indian fire use: deflating the legend" (PDF). Fire Management Today. Washington, D.C.: Forest Service of the U.S. Department of Agriculture. 65 (3): 31–33. Retrieved 2009-08-08.

- ↑ Krech III, Shepard (1999). The ecological Indian: myth and history (1 ed.). New York, New York: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. pp. 101–122. ISBN 0-393-04755-5.

- ↑ Neil G. Sugihara; Jan W. Van Wagtendonk; Kevin E. Shaffer; Joann Fites-Kaufman; Andrea E. Thode, eds. (2006). "17". Fire in California's Ecosystems. University of California Press. p. 417. ISBN 978-0-520-24605-8.

- ↑ K., Agee, James (1993). Fire ecology of Pacific Northwest forests. Washington, D.C.: Island Press. ISBN 1559632291. OCLC 682118318.

- ↑ William., Cronon, (2003). Changes in the land : Indians, colonists, and the ecology of New England. Demos, John. (1st rev. ed., 20th-anniversary ed.). New York: Hill and Wang. ISBN 9780809016341. OCLC 51886348.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Williams, G.W. (Summer 2000). "Reintroducing Indian-type fire: Implications for land managers". Fire Management today. 60 (3): 40–48.

- 1 2 Williams, G.W. (Summer 2004). "American Indian Fire Use in the Arid West". Fire Management Today. 64 (3): 10–14.

- ↑ Lake, F. K., Wright, V., Morgan, P., McFadzen, M., McWethy D., Stevens-Rumann, C. (2017). "Returning Fire to the Land: Celebrating Traditional Knowledge and Fire" (PDF). Journal of Forestry. 115 (5): 343–353.

![]()