Mori Ōgai

| Mori Ōgai | |

|---|---|

Mori Ōgai | |

| Native name | 森 鷗外 |

| Born |

February 17, 1862 Tsuwano, Shimane, Japan |

| Died | July 8, 1922 (aged 60) |

| Allegiance |

|

| Service/ |

|

| Years of service | 1882–1916 |

| Rank | Surgeon General of the Imperial Japanese Army (Lieutenant General) |

| Battles/wars | |

| Awards |

Grand Cordon of the Order of the Rising Sun Grand Cordon of the Order of the Sacred Treasure Order of the Golden Kite, 3rd Class |

| Other work | Translator, novelist and poet |

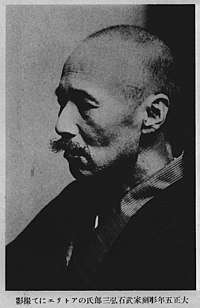

Lieutenant-General Mori Rintaro (森林太郎, February 17, 1862 – July 8, 1922), known by his pen name Mori Ōgai (森鴎外), was a Japanese Army Surgeon general officer, translator, novelist, poet and father of famed author Mari Mori. He obtained his medical license at a very young age and introduced translated German literary works to the Japanese public. Mori Ōgai also was considered the first to successfully express the art of western poetry into Japanese.[1] He wrote many works and created many writing styles. The Wild Geese (1911–13) is considered his major work. After his death, he was considered one of the leading writers who modernized Japanese literature.

Biography

Early life

Mori was born as Mori Rintarō (森 林太郎) in Tsuwano, Iwami Province (present-day Shimane Prefecture). His family were hereditary physicians to the daimyō of the Tsuwano Domain. As the eldest son, it was assumed that he would carry on the family tradition; therefore he was sent to attend classes in the Confucian classics at the domain academy, and took private lessons in rangaku and Dutch.

In 1872, after the Meiji Restoration and the abolition of the domains, the Mori family relocated to Tokyo. Mori stayed at the residence of Nishi Amane, in order to receive tutoring in German, which was the primary language for medical education at the time. In 1874, he was admitted to the government medical school (the predecessor for Tokyo Imperial University's Medical School), and graduated in 1881 at the age of 19, the youngest person ever to be awarded a medical license in Japan. It was also during this time that he developed an interest in literature, reading extensively from the late-Edo period popular novels, and taking lessons in Chinese poetry and literature.

Early career

After graduation, Mori enlisted in the Imperial Japanese Army as a medical officer, hoping to specialize in military medicine and hygiene. He was commissioned as a deputy surgeon (lieutenant) in 1882.

Mori was sent by the Army to study in Germany (Leipzig, Dresden, Munich, and Berlin) from 1884 to 1888. During this time, he also developed an interest in European literature. As a matter of trivia, Mori Ōgai is the first Japanese known to have ridden on the Orient Express.

One of his major accomplishments was his ability to create works using a style of "translation" that he obtained from his experience in European culture.[2]

Upon his return to Japan, he was promoted to surgeon first class (captain) in May 1885; after graduating from the Army War College in 1888, he was promoted to senior surgeon, second class (lieutenant colonel) in October 1889. Now a high-ranking army doctor, he pushed for a more scientific approach to medical research, even publishing a medical journal out of his own funds.

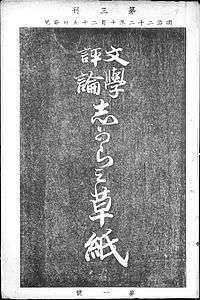

Meanwhile, he also attempted to revitalize modern Japanese literature and published his own literary journal (Shigarami sōshi, 1889–1894) and his own book of poetry (Omokage, 1889). In his writings, he was an "anti-realist", asserting that literature should reflect the emotional and spiritual domain. The short story "The Dancing Girl" (舞姫, Maihime, 1890) described an affair between a Japanese man and a German woman.

In May 1893, Mori was promoted to senior surgeon, first class (colonel). In 1899, he married Akamatsu Toshiko, daughter of Admiral Akamatsu Noriyoshi, a close friend of Nishi Amane. He divorced her the following year under acrimonious circumstances that irreparably ended his friendship with Nishi.

Later career

At the start of the First Sino-Japanese War of 1894–1895, Mori was sent to Manchuria and, the following year, to Taiwan. In February 1899, he was appointed head of the Army Medical Corps with the rank of surgeon major-general and was based in Kokura, Kyūshū. His transfer was because of his responses to fellow doctors and his criticism about their fields of research in the Japanese Medical Journal of which he was editor.[3] In 1902, he was reassigned to Tokyo. He was attached to a division in the Russo-Japanese War, based out of Hiroshima.

In 1907, Mori was promoted to Surgeon General of the Army (lieutenant general), the highest post within the Japanese Army Medical Corps, and became head of the Imperial Fine Arts Academy, which is now the Japan Art Academy. Also in the same year, he also became chairman of the BRC(Beriberi Research Council) and headed their first major research case. Mori Ōgai discovered the cause of the beriberi disease and managed to create a foundation to build a remedy, but the problem was only resolved after his death.[4]

He was appointed director of the Imperial Museum when he retired in 1916. Mori Ōgai then died of renal failure and pulmonary tuberculosis six years later, aged 60.

Literary work

Although Mori did little writing from 1892 to 1902, he continued to edit a literary journal (Mezamashi gusa, 1892–1909). He also produced translations of the works of Goethe, Schiller, Ibsen, Hans Christian Andersen, and Hauptmann.

It was during the Russo-Japanese War (1904–05) that Mori started keeping a poetic diary. After the war, he began holding tanka writing parties that included several noted poets such as Yosano Akiko.

Mori Ōgai helped found a new magazine called Subaru (literary magazine) in 1909 with the help of others such as Yosano Akiko and Yosano Tekkan.

His later works can be divided into three separate periods. From 1909 to 1912, he wrote mostly fiction based on his own experiences. This period includes Vita Sexualis, and his most popular novel, Gan (雁 The Wild Geese, 1911–13), which is set in 1881 Tokyo and was filmed by Shirō Toyoda in 1953 as The Mistress.

In 1909, he released his novel Vita Sexualis which was abruptly banned a month later. Authorities deemed his work too sexual and dangerous to public morals.[5] Mori Ōgai, during the period he was writing Vita Sexualis, focused on making a statement regarding the current literary trends of modern Japanese literature. He approached the trend on sexuality and individualism by describing them as a link between body and soul. Ōgai points out problems concerning the art and literature world in the 19th century in his work. His writing style, depicted from the Meiji government's perspective, derived from naturalism and was implemented with his thoughts that were brought up from writers who focused on the truth.[3]

His later works link his concerns with the Ministry of Education regarding the understanding of "intellectual freedom" and how they police and dictate the potential of literature.[3]

From 1912 to 1916, he wrote mostly historical stories. Deeply affected by the death of General Nogi Maresuke in 1912, he explored the impulses of self-destruction, self-sacrifice and patriotic sentiment. This period includes Sanshō Dayū (山椒大夫), and Takasebune (高瀬舟).

From 1916 to 1921, he turned his attention to biographies of three Edo period doctors.[6]

Legacy

As an author, Mori is considered one of the leading writers of the Meiji period. In his literary journals, he instituted modern literary criticism in Japan, based on the aesthetic theories of Karl von Hartmann.

A house which Mori lived in is preserved in Kokurakita Ward in Kitakyūshū, not far from Kokura Station. Here he wrote Kokura Nikki ("Kokura Diary"). His birthhouse is also preserved in Tsuwano. The two one-story houses are remarkably similar in size and in their traditional Japanese style.

One of Mori's daughters, the author Mori Mari, who was nineteen years old at the time of his death, wrote extensively about her relationship with her father. Starting with her 1961 novella, A Lovers' Forest (恋人たちの森 Koibito Tachi no Mori), she wrote tragic stories about love affairs between older men and boys in their late teens which influenced the creation of the Yaoi genre, stories about male-male relationships, written by women for women, that began to appear in the nineteen seventies in Japanese novels and comics.[7] Mori's sister, Kimiko, married Koganei Yoshikiyo. Hoshi Shinichi was one of their grandsons.

Cultural references

Ōgai Mori, along with many other historical figures from the Meiji Restoration is a character in the historical fiction novel Saka no Ue no Kumo by Ryōtarō Shiba. He also plays a significant part in the historical fantasy novel Teito Monogatari by Hiroshi Aramata.

Mori is a character in the manga and anime adaptation of Bungo Stray Dogs. Bungo Stray Dogs uses the names, stories and biographical details of authors to create its characters.

Honours

From the Japanese Wikipedia article

Decorations

- Order of the Golden Kite, 3rd Class (1 April 1906; Fourth Class: 20 September 1895)

- Grand Cordon of the Order of the Sacred Treasure (24 April 1915; Third Class: 29 November 1904; Fifth Class: 25 November 1896; Sixth Class: 24 November 1894)

- Grand Cordon of the Order of the Rising Sun (7 November 1915; Second Class: 1 April 1906; Sixth Class: 20 September 1895)

Court ranks in the order of precedence

- Senior sixth rank (16 December 1893)

- Fifth rank (15 November 1895)

- Fourth rank (13 September 1904)

- Senior fourth rank (20 October 1909)

Selected works

- Maihime (舞姫 The Dancing Girl (1890))

- Utakata no ki (うたかたの記 Foam on the Waves (1890))

- Fumizukai (文づかひ The Courier (1891))

- Wita sekusuarisu (ヰタ・セクスアリス Vita Sexualis (1909))

- Seinen (青年 Young Men (1910))

- Gan (雁 The Wild Geese (1911–13))

- Okitsu Yagoemon no isho (興津弥五右衛門の遺書 The Last Testament of Okitsu Yagoemon (1912))

- Sanshō Dayū (山椒大夫 Sanshō the Steward (1915))

- Takasebune (高瀬舟 The Boat on the Takase River (1916))

- Shibue Chūsai (渋江抽斎 Shibue Chusai (1916))

- Izawa Ranken (伊澤蘭軒 Izawa Ranken (1916–17))

- Hojo Katei (北条霞亭 Hojo Katei (1917–18))

Film

- Sansho the Bailiff, a milestone in Japanese movie history,[8] is based on a short story by the author.[9]

Translations

- The Columbia Anthology of Modern Japanese Literature: From Restoration to Occupation, 1868–1945 (Modern Asian Literature Series) (vol. 1), ed. J. Thomas Rimer and Van C. Gessel. 2007. Contains "The Dancing Girl," and "Down the Takase River."

- Modern Japanese Stories: An Anthology, ed. Ivan Morris. 1961. Rutland, Vt.: Charles E. Tuttle, 1966. Contains "Under Reconstruction."

- The Historical Fiction of Mori Ôgai, ed. David A. Dilworth and J. Thomas Rimer. 1977. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1991. A one-volume paperback edition of an earlier two-volume collection of stories.

- Modern Japanese Stories: An Anthology, ed. Ivan Morris. 1961. Rutland, Vt.: Charles E. Tuttle, 1966. Contains "Under Reconstruction."

- Sansho-Dayu and Other Short Stories, trans. Tsutomu Fukuda. Tokyo: Hokuseido Press, 1970.

- Vita Sexualis, trans. Kazuji Ninomiya and Sanford Goldstein. 1972. Boston: Tuttle Publishing, 200.

- The Wild Geese, trans. Ochiai Kingo and Sanford Goldstein. Boston: Tuttle Publishing, 1959.

- The Wild Goose, trans. Burton Watson. 1995. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Center for Japanese Studies, 1998.

- Youth and Other Stories (collection of stories), ed. J. Thomas Rimer. 1994. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1995

See also

Further reading

- Salomon, Harald (compiler). Mori Ôgai: A Bibliography of Western-language Materials (Volume 10 of Izumi (Series)). Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, 2008. ISBN 3447058048, 9783447058049. See preview at Google Books.

References

- ↑ "Mori Ogai". 22 July 2007.

- ↑ Nagashima, Yōichi. "From "Literary Translation" to "Cultural Translation": Mori Ōgai and the Plays of Henrik Ibsen." Japan Review, no. 24 (2012): 85–104. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41592689.

- 1 2 3 Hopper, Helen M. "Mori Ogai's Response to Suppression of Intellectual Freedom, 1909–12." Monumenta Nipponica 29, no. 4 (1974): 381–413. doi:10.2307/2383893.

- ↑ Alexander Bay; Book review: Ōgai Mori rintarō to kakkefunsō. East Asian Science, Technology and Society 1 December 2011; 5 (4): 573–579. doi: https://doi-org.ezproxy.lib.ou.edu/10.1215/18752160-1458784

- ↑ Mori, Ōgai. Vita sexualis. Rutland, Vt: C.E. Tuttle Co, 1972, p.9

- ↑ Marcus, Marvin. "Mori Ōgai and The Biographical Quest." Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 51, no. 1 (1991): 233–62. doi:10.2307/2719246.

- ↑ Vincent, Keith (2007). "A Japanese Electra and Her Queer Progeny". In Lunning, Frenchy. Mechademia 2. University of Minnesota Press. p. 64. ISBN 9780816652662.

- ↑ "Tales and Tragedies of Kenjo Mozoguchi". Retrieved 2015-03-02.

- ↑ "Sansho the Bailiff". Retrieved 2015-03-12.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |