Congress of Manastir

The Congress of Manastir (Albanian: Kongresi i Manastirit) was an academic conference held in the city of Manastir (Bitola) from November 14 to November 22, 1908, with the goal of standardizing the Albanian alphabet. November 22 is now a commemorative day in Albania, Kosovo, and the Republic of Macedonia, as well as among the Albanian diaspora, known as Alphabet Day (Albanian: Dita e Alfabetit).[1][2] Prior to the Congress, the Albanian language was represented by a combination of six or more[3] distinct alphabets, plus a number of sub-variants.[4]

Participants

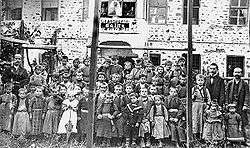

The congress was held by the Union Association (Albanian language: Bashkimi) literary society at the house of Fehim Zavalani, which served as the place of the Union. The participants in the congress were prominent figures of the cultural and political life from Albanian-inhabited territories in the Balkans, as well as throughout the Albanian diaspora. There were fifty delegates, representing twenty-three Albanian-inhabited cities, towns, and cultural and patriotic associations of whom thirty-two had voting rights in the congress, and eighteen were observers. Among prominent delegates were Gjergj Fishta, Ndre Mjeda, Mit'hat Frashëri, Sotir Peçi, Shahin Kolonja, and Gjergj D. Qiriazi. Zavalani, held the introductory speech led the congress. Other delegates of the congress from the family included Izet Zavalani, delegate of Florina and Gjergj Zavalani.[4]

Proceedings

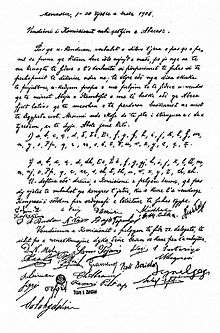

The speeches of the first two days with regard to the alphabet were general in character, and helped to create the atmosphere in which to carry out the serious work. The representatives understood the importance of unity, regardless which alphabet was chosen. Gjergj Fishta who praised the work of Bashkimi alphabet declared “I have not come here to defend any one of the alphabets, but I have come here to unite with you and adopt that alphabet which the Congress decides upon as most useful for uplifting the people”. The audience was deeply moved by Fishta. Hodja Ibrahim Effendi, who was a Muslim clergymen, rushed to Fishta and embraced him with tears in his eyes.[5] At the beginning of the Congress, the delegates elected a commission consisting of eleven members (four Muslim, four Orthodox and four Catholic) to bring a decision before the full membership.[6] Gjergj Fishta was elected chairman of the commission, Parashqevi Qiriazi chairwoman and Mit'hat Frashëri its vice-chairman. Luigj Gurakuqi became the secretary of the commission while the other five members of the commission were Bajo Topulli, Ndre Mjeda, Shahin Kolonja, Gjergj Qiriazi and Sotir Peçi. Mit'hat Frashëri was also elected chairman of the congress. The delegates took a besa to accept the decision of the committee. The committee deliberated on the question of a common alphabet for three successive days.[5] It gave the besa that nothing would be known before the ultimate decision. However, the Congress was unable to choose only one alphabet and opted for a compromise solution of using both the Istanbul and Bashkimi alphabets with some changes to reduce the differences between them. Usage of the alphabet of Istanbul declined rapidly and it became extinct over the following years and Albania declared its independence.[5] The Bashkimi alphabet is at the origin of the official alphabet of the Albanian language in use today. Gjergj Fishta noted that the German language had two written scripts to those disappointed because there was not one alphabet chosen but two. After some discussion, it was accepted by all the delegates the decision for both Bashkimi and Istanbul alphabet. Also it was agreed to have all the Albanian clubs to report to the Manastri’s Bashkimi club about developments in their areas every month. Another agreement was to hold another congress in Yanya on 10 July 1910.[5] On November 20, when the congress was in its last days, Hodja Vildan, Fazil Pasha and Colonel Riza, three members of Albanian club of Istanbul arrived. Their purpose was to attend the congress and later advise Albanian clubs that operated throughout Albania. The participants of congress firstly thought their aim was to protect writing of Albanian with Turkish alphabet. However, Hodja Vildan nullified this concerns. He denounced Sultan Abdul Hamid and protected the importance of union among the Albanians for defence of themselves and empire. Vildan argued that it was the right of Albanians to use Latin alphabet and this would be a tool for progress. He did not take position on the direction of writing and matters of religion. The same ideas were protected by him in other places three members of Albanian club of Istanbul visited.[7]

Legacy

The adoption of a Latin character-based Albanian alphabet was considered an important step for Albanian unification.[7][8][9][10] Some Albanian Muslims and clerics (who with the Ottoman government preferred an Arabic-based Albanian alphabet) showed their opposition toward the Latin alphabet because of concerns that it undermined ties with the Muslim world.[7][8][9] For the Ottoman government the situation was alarming because the Albanians were the largest Muslim community in the European part of the empire (Istanbul excluded). The Albanian national movement was a proof that not only Christians had national feelings and Islam could not keep Ottoman Muslims united. In these circumstances the Ottoman state organised a congress in Debar in 1909 with the intention that Albanians there declare themselves as Ottomans, promise to defend its territorial sovereignty and adopt an Albanian Arabic character script.[10] However they faced a strong opposition from nationally minded Albanians and the Albanian element took total control of the proceedings.[7] While the congress was on progress people of CUP in Tirane orchestrated an demonstration aimed at Latin alphabet and the local branch of Bashkimi club, the organizer of the Manastir congress. Talat Bey, the interior minister, claimed that the Albanian population supported use of the Turkish alphabet and stayed against the Latin one. However the Bashkimi club did not stop the activity and organized a congress with 120 attendees in Elbasan.[9]

Due to the alphabet matter and other Young Turk policies, relations between Albanian elites and nationalists and Ottoman authorities broke down.[10][11] Though at first Albanian nationalist clubs were not curtailed, the demands for political, cultural and linguistic rights eventually made the Ottomans adopt measures to repress Albanian nationalism which resulted in two Albanian revolts (1910 and 1912) toward the end of Ottoman rule.[12][13][14][14]

The congress represents one of the most important dates of Albanian culture,[15] and the biggest event for the Albanian people after the League of Prizren, not only because of the decisions taken, but because those decisions would be legally implemented by the Ottoman authorities.[16] In 2008 festivities were organized in Bitola, Tirana and Pristina to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the congress. In Albania, Kosovo and Albanian-majority areas in Macedonia in all schools the first teaching hour was dedicated to honour the Congress and give more information to the students about it.

See also

References

- ↑ Në Maqedoni festohet Dita e Alfabetit [Alphabet Day celebrated in Macedonia] (in Albanian), portalb.mk, 2012-11-22, retrieved 2013-09-24

- ↑ The message of the Prime Minister of the Republic of Kosovo, Hashim Thaci on the event if the 103rd anniversary of the session of the Congress of Manastir on November 14, 1908, Kosovo Prime Minister's Office, November 2011, retrieved 2013-09-24

- ↑ "Perse u zgjodhen dy alfabete" [Why two alphabets were chosen]. Materiale e Dokumente. Studime Filologjike (in Albanian). No. 4. Tirana: Akademia e Shkencave e RPSSH, Instituti i Gjuhesise dhe i Letersise. 1988. pp. 149–159. ISSN 0563-5780

Partial publication of the memo of Gjergj Qiriazi to the Austro-Hungarian consulate in Manastir, dated 25.05.1909, 20 pages - 1 2 Frances Trix (1997), Alphabet conflict in the Balkans: Albanian and the Congress of Monastir, 128, International Journal of the Sociology of Language, pp. 1–24, ISSN 0165-2516

- 1 2 3 4 Gawrych 2006, p. 165

- ↑ Entangled Histories of the Balkans – Volume One: National Ideologies and Language Policies. p. 504.

- 1 2 3 4 Skendi 1967, pp. 370–378

- 1 2 Duijzings 2000, p. 163.

- 1 2 3 Gawrych 2006, p. 182.

- 1 2 3 Nezir-Akmese 2005, p. 96.

- ↑ Saunders 2011, p. 97.

- ↑ Nezir-Akmese 2005, p. 97.

- ↑ Poulton 1995, p. 66.

- 1 2 ShawShaw 1977, p. 288.

- ↑ "Six successful years of SEEU". South Eastern European University. Archived from the original on 2008-05-27. Retrieved 2008-11-20.

- ↑ Mustafa, Avzi (2014-03-19), Kongresi i dytë i Manastirit [Second Congress of Monastir] (in Albanian), Dielli,

Kongresi i parë i Manastirit, pas Lidhjes së Prizrenit, ishte ngjarja më e madhe e popullit shqiptar, që u hapi rrugën jo vetëm të kërkesave legjitime të shqiptarëve, por që edhe ato kërkesa të realizohen në mënyrë legale dhe të jenë të lejuara nga qeveria e Sulltanit përmes rrugës parlamentare. translated

First Congress of Monastir, after the League of Prizren, was the biggest event for the Albanian people, which not only opened the path to the legitimate demands of the Albanians, but those demands to come implemented pretty soon in a legal way by the Sultan's government through parliamentary channels

Sources

- Duijzings, Gerlachlus (2002). "Religion and the politics of 'Albanianism': Naim Frasheri's Bektashi writings". In Schwanders-Sievers, Stephanie; Fischer, Bernd J. Albanian Identities: Myth and History. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. pp. 60–69. ISBN 9780253341891.

- Gawrych, George (2006). The Crescent and the Eagle: Ottoman rule, Islam and the Albanians, 1874–1913. London: IB Tauris. ISBN 9781845112875.

- Lloshi, Xhevat (2008). Rreth Alfabetit te Shqipes [About the Albanian Alphabet]. Logos.

- Nezir-Akmese, Handan (2005). The Birth of Modern Turkey: The Ottoman Military and the March to WWI. London: IB Tauris. ISBN 9781850437970.

- Osmani, Tomor (1999). "Historia e alfabetit" [History of the Alphabet]. Udha e shkronjave shqipe [The Pathway of the Albanian Letters] (in Albanian). pp. 461–496.

- Poulton, Hugh (1995). Who are the Macedonians?. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 9781850652380.

- Saunders, Robert A. (2011). Ethnopolitics in Cyberspace: The Internet, Minority Nationalism, and the Web of Identity. Lanham: Lexington Books. ISBN 9780739141946.

- Shaw, Stanford J.; Shaw, Ezel Kural (1977). History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey: Volume 2, Reform, Revolution, and Republic: The Rise of Modern Turkey 1808-1975. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521291668.

- Skendi, Stavro (1967). The Albanian national awakening. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9781400847761.