Metrication

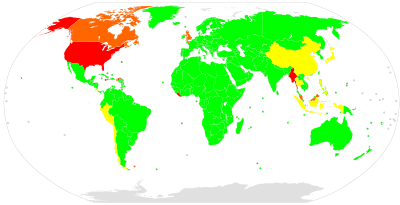

Metrication or metrification is conversion to the metric system of units of measurement.[2] Worldwide, there has been a long process of independent conversions of countries from various local and traditional systems, beginning in France during the 1790s and spreading widely over the following two centuries, but the metric system has not been fully adopted in all countries and sectors.

Overview

As of 2017, seven countries have not committed to completing the process of full metrication:[3]

- The United States (and its associated states the Federated States of Micronesia, Marshall Islands and Palau), officially using U.S. customary units.

- Liberia, officially using U.S. customary units.[4]

- Myanmar, officially using Burmese units.

- Belize [5]

- However, both Myanmar and Liberia are reportedly essentially metric, even without official legislation.[6]

In the United Kingdom metric is the official system for most regulated trading by weight or measure purposes, but some imperial units remain the primary official unit of measurement. For example, miles, yards, and feet remain the official units for road signage – and use of imperial units is widespread.[7][8] The Imperial pint also remains a permitted unit for milk in returnable bottles and for draught beer and cider in British pubs.[7] Imperial units are also legal for use alongside metric units on food packaging and price indications for goods sold loose, and may be used exclusively where a product is sold by description, rather than by weight/mass/volume. E.g. Television screen and clothing sizes tend to be denominated in inches only, but a piece of material priced per inch would be unlawful unless the metric price was also shown.

Some sources now identify Liberia as metric, and the government of Myanmar has stated that the country would metricate with a goal of completion by 2019.[9][10] Both Myanmar and Liberia are substantially metric countries, trading internationally in metric units. Visiting advocates of metrication have stated that they use metric units for many things internally with exceptions such as old petrol pumps in Myanmar, calibrated in British Imperial gallons. These and other countries have adopted metric measures to some degree through international trade and standardisation[11] for example, Sierra Leone switched to selling fuel by the litre in May 2011.[12] The United States mandated the acceptance of the metric system in 1866 for commercial and legal proceedings, without displacing their customary units.[13] The United Kingdom followed suit in 1897 and did not make the use of metric units compulsory for most purposes until 1995.

In 1971 the US National Bureau of Standards completed a three-year study of the impact of increasing worldwide metric use on the US. The study concluded with a report to Congress entitled A Metric America – A Decision Whose Time Has Come. Since then metric use has increased in the US, principally in the manufacturing and educational sectors. Public Law 93-380, enacted 21 August 1974, states that it is the policy of the US to encourage educational agencies and institutions to prepare students to use the metric system of measurement with ease and facility as a part of the regular education program. On 23 December 1975, President Gerald Ford signed Public Law 94-168, the Metric Conversion Act of 1975. This act declares a national policy of coordinating the increasing use of the metric system in the US It established a US Metric Board whose functions as of 1 October 1982 were transferred to the Dept of Commerce, Office of Metric Programs, to coordinate the voluntary conversion to the metric system.[14]

Most countries have adopted the metric system officially over a transitional period where both units are used for a set period of time. Some countries such as Guyana, for example, have officially adopted the metric system, but have had some trouble over time implementing it.[15] Antigua and Barbuda, also "officially" metric, is moving toward total implementation of the metric system, but slower than expected. The government had announced that they have plans to convert their country to the metric system by the first quarter of 2015.[16] Other Caribbean countries such as Saint Lucia are officially metric but are still in the process toward full conversion.[17]

The European Union used the Units of Measure Directive to attempt to achieve a common system of weights and measures and to facilitate the European Single Market. Throughout the 1990s, the European Commission helped accelerate the process for member countries to complete their metric conversion processes. Among them is the United Kingdom where laws in some or all contexts mandate or permit many imperial measures, such as miles and yards for road-sign distances, road speed limits in miles per hour, pints of beer, and inches for clothes.[18] The United Kingdom secured permanent exemptions for the mile and yard in road markings, and (with Ireland) for the pint (Imperial) of draught beer sold in pubs[19] (see Metrication in the United Kingdom). In 2007, the European Commission also announced that (to appease British public opinion and to facilitate trade with the United States) it was to abandon the requirement for metric-only labelling on packaged goods, and to allow dual metric–imperial marking to continue indefinitely.[19]

Other countries using the imperial system completed official metrication during the second half of the 20th century or the first decade of the 21st century. The most recent to complete this process was the Republic of Ireland, which began metric conversion in the 1970s and completed it in early 2005.[20]

In January 2007 NASA decided to use metric units for all future moon missions, in line with the practice of other space agencies.[21]

The United States, the United Kingdom, and Canada have some active opposition to metrication, particularly where updated weights and measures laws would make obsolete historic systems of measurement. Other countries, like France and Japan, that once had significant popular opposition to metrication now have complete acceptance of metrication.

Before the metric system

The Roman empire used the pes (foot) measure. This was divided into 12 unciae ("inches"). The libra ("pound") was another measure that had wide effect on European weight and currency long after Roman times, e.g. lb, £. The measure came to vary greatly over time. Charlemagne was one of several rulers who launched reform programmes of various kinds to standardise units for measure and currency in his empire, but there was no real general breakthrough.

In medieval Europe, local laws on weights and measures were set by trade guilds on a city-by-city basis. For example, the ell or elle was a unit of length commonly used in Europe, but its length varied from 40.2 centimetres in one part of Germany to 70 centimetres in The Netherlands and 94.5 centimetres in Edinburgh. A survey of Switzerland in 1838 revealed that the foot had 37 different regional variations, the ell had 68, there were 83 different measures for dry grain, 70 measures for fluids and 63 different measures for "dead weights".[22] When Isaac Newton wrote Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica in 1687, he quoted his measurements in Parisian feet so readers could understand the size. Examples of efforts to have local intercity or national standards for measurements include the Scottish law of 1641, and the British standard imperial system of 1824, which is still commonly used in the United Kingdom. At one time Imperial China had successfully standardised units for volume throughout its territory, but by 1936 official investigations uncovered 53 values for the chi varying from 200 millimetres to 1250 millimetres; 32 values of the cheng, between 500 millilitres and 8 litres; and 36 different tsin ranging from 300 grams to 2500 grams.[23] However, revolutionary France was to produce the definitive International System of Units which has come to be used by most of the world today.

The desire for a single international system of measurement came from growing international trade and the need to apply common standards to goods. For a company to buy a product produced in another country, they need to ensure that the product would arrive as described. The medieval ell was abandoned in part because its value could not be standardised. One primary advantage of the International System of Units is simply that it is international, and the pressure on countries to conform to it grew as it became increasingly an international standard. However, it also simplified the teaching and learning of measurement as all SI units are based on a handful of base units (in particular, the metre, kilogram and second cover the majority of everyday measurements), using decimal prefixes to cover all magnitudes. This contrasts with pre-metric units, which largely have names that do not relate directly to one another (e.g. inch, foot, yard, mile) and are related to one another by inconsistent ratios which must simply be memorised (e.g. 12, 3, 1760). As the values in an SI expression are always decimal (i.e. without vulgar fractions) and mixed units (such as "feet and inches") are not used with SI, measurements are easy to add or multiply. Moreover, scientific measurement and calculation are greatly simplified as the units for electricity, force etc. are part of the SI system and hence are all interrelated in a coherent manner (e.g. 1 J = 1 kg·m2·s−2 = 1 V·A·s). Standardisation of measures has contributed significantly to the industrial revolution and technological development in general. SI is not the only example of international standardisation; several powerful international standardisation organisations exist for various industries, such as the International Organisation for Standardisation (ISO), the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC), and the International Telecommunication Union (ITU).

Forerunners of the metric system

Decimal numbers are an essential part of the metric system, with only one base unit and multiples created on the decimal base, the figures remain the same. This simplifies calculations. Although the Indians used decimal numbers for mathematical computations, it was Simon Stevin who in 1585 first advocated the use of decimal numbers for everyday purposes in his booklet De Thiende (old Dutch for 'the tenth'). He also declared that it would only be a matter of time before decimal numbers were used for currencies and measurements. His notation for decimal fractions was clumsy, but this was overcome with the introduction of the decimal point, generally attributed to Bartholomaeus Pitiscus who used this notation in his trigonometrical tables (1595).[24]

In his Essay towards a Real Character and a Philosophical Language, published in 1668, John Wilkins proposed a system of measurement that was very similar in concept to today's metric system. He proposed retaining the second as the basic unit of time and proposed that the length of a pendulum which crossed the zero position once a second (i.e. had a period of two seconds) should be the base unit of length. This length, for which he proposed the name "standard", would have been 994 mm. His base unit of mass, which he proposed calling a "hundred", would have been the mass of a cubic standard of distilled rainwater. The names that he proposed for decimal multiples and subunits of his base units of measure were the names of units of measure that were in use at the time.[25][26]

In 1670, Gabriel Mouton published a proposal that was in essence similar to Wilkins' proposal, except that his base unit of length would have been 1/1000 of a minute of arc (about 1.852 m) of geographical latitude. He proposed calling this unit the virga. Rather than using different names for each unit of length, he proposed a series of names that had prefixes, rather like the prefixes found in SI.[27]

In 1790, Thomas Jefferson submitted a report to the United States Congress in which he proposed the adoption of a decimal system of coinage and of weights and measures. He proposed calling his base unit of length a "foot" which he suggested should be either 3⁄10 or 1⁄3 of the length of a pendulum that had a period of one second – that is 3⁄10 or 1⁄3 of the "standard" proposed by Wilkins over a century previously. This would have equated to 11.755 English inches (29.8 cm) or 13.06 English inches (33.1 cm). Like Wilkins, the names that he proposed for multiples and subunits of his base units of measure were the names of units of measure that were in use at the time.[28] The great interest in geodesy during this era, and the measurement system ideas that developed, influenced how the continental US was surveyed and parceled. The story of how Jefferson's full vision for the new measurement system came close to displacing the Gunter chain and the traditional acre, but ended up not doing so, is explored in Andro Linklater's Measuring America.[29]

Adoption of metric weights and measures

During the nineteenth century the metric system of weights and measures proved a convenient political compromise during the unification processes in the Netherlands, Germany and Italy. In 1814, Portugal became the first country not part of the French Empire to officially adopt a metric system. Spain found it expedient in 1858 to follow the French example and within a decade Latin America had also adopted the metric system. There was considerable resistance to metrication in the United Kingdom and in the United States, though once the United Kingdom announced its metrication program in 1965, the Commonwealth followed suit.

France

The introduction of the metric system into France in 1795 was done on a district by district basis with Paris being the first district, but by modern standards the transition was poorly managed. Although thousands of pamphlets were distributed, the Agency of Weights and Measures who oversaw the introduction underestimated the work involved. Paris alone needed 500,000 metre sticks, yet one month after the metre became the sole legal unit of measure, they only had 25,000 in store.[8]: 269 This, combined with other excesses of the Revolution and the high level of illiteracy made the metric system unpopular.

Napoleon himself ridiculed the metric system, but as an able administrator, recognised the value of a sound basis for a system of measurement and under the décret impérial du 12 février 1812 (imperial decree of 12 February 1812), a new system of measure – the mesures usuelles or "customary measures" was introduced for use in small retail businesses – all government, legal and similar works still had to use the metric system and the metric system continued to be taught at all levels of education.[30] The names of many units used during the ancient regime were reintroduced, but were redefined in terms of metric units. Thus the toise was defined as being two metres with six pied making up one toise, twelve pouce making up one pied and twelve lignes making up one pouce. Likewise the livre was defined as being 500 g, each livre comprising sixteen once and each once eight gros and the aune as 120 centimetres.[31]

Louis Philippe I by means of the La loi du 4 juillet 1837 (the law of 4 July 1837) effectively revoked the use of mesures uselles by reaffirming the laws of measurement of 1795 and 1799 to be used from 1 May 1840.[32][33] However, many units of measure, such as the livre (for half a kilogram), remained in everyday use for many years,[33][34] and to a residual extent up to this day.

The Portuguese metric system

In August 1814, Portugal officially adopted the metric system but with the names of the units substituted by Portuguese traditional ones. In this system the basic units were the mão-travessa (hand) = 1 decimetre (10 mão-travessas = 1 vara (yard) = 1 metre), the canada = 1 liter and the libra (pound) = 1 kilogram.[35]

The Dutch metric system

The Netherlands first used the metric system and then, in 1812, the mesures usuelles when it was part of the First French Empire. Under the Royal decree of 27 March 1817 (Koningklijk besluit van den 27 Maart 1817), the newly formed Kingdom of the Netherlands abandoned the mesures usuelles in favour of the "Dutch" metric system (Nederlands metrisch stelsel) in which metric units were given the names of units of measure that were then in use. Examples include the ons (ounce) which was defined as being 100 g.[36]

The German Zollverein

At the outbreak of the French Revolution, much of modern-day Germany and Austria were part of the Holy Roman Empire which had become a loose federation of kingdoms, principalities, free cities, bishoprics and other fiefdoms, each with its own system of measurement, though in most cases such system were loosely derived from the Carolingian system instituted by Charlemagne a thousand years earlier.

During the Napoleonic era, there was a move among some of the German states to reform their systems of measurement using the prototype metre and kilogram as the basis of the new units. Baden, in 1810, for example, redefined the Ruthe (rods) as being 3.0 m exactly and defined the subunits of the Ruthe as 1 Ruthe = 10 Fuß (feet) = 100 Zoll (inches) = 1,000 Linie (lines) = 10,000 Punkt (points) while the Pfund was defined as being 500 g, divided into 30 Loth, each of 16.67 g.[37][38] Bavaria, in its reform of 1811, trimmed the Bavarian Pfund from 561.288 g to 560 g exactly, consisting of 32 Loth, each of 17.5 g[39] while the Prussian Pfund remained at 467.711 g.[40]

After the Congress of Vienna there was a degree of commercial cooperation between the various German states resulting in the setting of the German Customs Union (Zollverein). There were however still many barriers to trade until Bavaria took the lead in establishing the General German Commercial Code in 1856. As part of the code the Zollverein introduce the Zollpfund (Customs Pound) which was defined to be exactly 500 g and which could be split into 30 'lot'.[41] This unit was used for inter-state movement of goods, but was not applied in all states for internal use.

Although the Zollverein collapsed after the Austro-Prussian War of 1866, the metric system became the official system of measurement in the newly formed German Empire in 1872[8]:350 and of Austria in 1875.[42] The Zollpfund ceased to be legal in Germany after 1877.[43]

Italy

The Cisalpine Republic, a North Italian republic set up by Napoleon in 1797 with its capital at Milan first adopted a modified form of the metric system based in the braccio cisalpino (Cisalpine cubit) which was defined to be half a metre.[44] In 1802 the Cisalpine Republic was renamed the Italian Republic, with Napoleon as its head of state. The following year the Cisalpine system of measure was replaced by the metric system.[44]

In 1806, the Italian Republic was replaced by the Kingdom of Italy with Napoleon as its emperor. By 1812, all of Italy from Rome northwards was under the control of Napoleon, either as French Departments or as part of the Kingdom of Italy ensuring the metric system was in use throughout this region.

After the Congress of Vienna, the various Italian states reverted to their original system of measurements, but in 1845 the Kingdom of Piedmont and Sardinia passed legislation to introduce the metric system within five years. By 1860, most of Italy had been unified under the King of Sardinia Victor Emmanuel II and under Law 132 of 28 July 28, 1861 the metric system became the official system of measurement throughout the kingdom. Numerous Tavole di ragguaglio (Conversion Tables) were displayed in shops until 31 December 1870.[44]

Spain

Until the ascent of the Bourbon monarchy in Spain in 1700, each of the regions of Spain retained its own system of measurement. The new Bourbon monarchy tried to centralise control and with it the system of measurement. There were debates regarding the desirability of retaining the Castilian units of measure or, in the interests of harmonisation, adopting the French system.[45] Although Spain assisted Méchain in his meridian survey, the Government feared the French revolutionary movement and reinforced the Castilian units of measure to counter such movements. By 1849 however, it proved difficult to maintain the old system and in that year the metric system became the legal system of measure in Spain.[45]

The Government was urged by the Spanish Royal Academy of Science to approve the creation of a large-scale map of Spain in 1852. The following year Carlos Ibáñez e Ibáñez de Ibero was appointed to undertake this task. All the scientific and technical material had to be created. Carlos Ibáñez e Ibáñez de Ibero and Saavedra went to Paris to supervise the production by Brunner of a measuring instrument which they had devised and which they later compared with Borda's double-toise N°1 which was the main reference for measuring all geodetic bases in France and whose length was 3.8980732 metres.

In 1865 the triangulation of Spain was connected with that of Portugal and France. In 1866 at the conference of the Association of Geodesy in Neuchâtel, Ibáñez announced that Spain would collaborate in remeasuring the French meridian arc. In 1879 Ibáñez and François Perrier (representing France) completed the junction between the geodetic network of Spain and Algeria and thus completed the measurement of the French meridian arc which extended from Shetland to the Sahara.

In 1867 Russia, Spain and Portugal joined the "Europäische Gradmessung" (European Arc Measurement which would become the International Association of Geodesy). This same year at the second general conference of the European Arc Measurement held in Berlin, the question of an international standard unit of length was discussed in order to combine the measurements made in different countries to determine the size and shape of the Earth. The conference recommended the adoption of the metre and the creation of an international metre commission, according to the proposal of Johann Jacob Baeyer, Adolphe Hirsch and Carlos Ibáñez e Ibáñez de Ibero.

In November 1869 the French government issued invitations to join this commission. Spain accepted and Carlos Ibáñez e Ibáñez de Ibero took part in the Committee of preparatory research from the first meeting of the International Metre Commission in 1870. He became president of the permanent Committee of the International Metre Commission in 1872. In 1874 he was elected as president of the Permanent Commission of the European Arc Measurement. He also presided the General Conference of the European Arc Measurement held in Paris in 1875, when the association decided the creation of an international geodetic standard for the bases' measurement.[46] He represented Spain at the 1875 conference of the Metre Convention, which was ratified the same year in Paris. The Spanish geodesist was elected as the first president of the International Committee for Weights and Measures. His activities resulted in the distribution of a platinum and iridium prototype of the metre to all States parties to the Metre Convention during the first meeting of the General Conference on Weights and Measures in 1889. Theses prototypes defined the metre right up until 1960.

United Kingdom and the Commonwealth

In 1824 the Weights and Measures Act imposed one standard 'imperial' system of weights and measures on the British Empire.[47] The effect of this act was to standardise existing British units of measure rather than to align them with the metric system.

During the next eighty years a number of Parliamentary select committees recommended the adoption of the metric system, each with a greater degree of urgency, but Parliament prevaricated. A Select Committee report of 1862 recommended compulsory metrication, but with an "Intermediate permissive phase"; Parliament responded in 1864 by legalising metric units only for 'contracts and dealings'.[48] The United Kingdom initially declined to sign the Treaty of the Metre, but did so in 1883. Meanwhile, British scientists and technologists were at the forefront of the metrication movement – it was the British Association for the Advancement of Science that promoted the CGS system of units as a coherent system[49]: 109 and it was the British firm Johnson Matthey that was accepted by the CGPM in 1889 to cast the international prototype metre and kilogram.[50]

In 1895 another Parliamentary select committee recommended the compulsory adoption of the metric system after a two-year permissive period. The 1897 Weights and Measures Act legalised the metric units for trade, but did not make them mandatory.[48] A bill to make the metric system compulsory in order to enable the British industrial base to fight off the challenge of the nascent German base passed through the House of Lords in 1904, but did not pass in the House of Commons before the next general election was called. Following opposition by the Lancashire cotton industry, a similar bill was defeated in 1907 in the House of Commons by 150 votes to 118.[48]

In 1965 Britain commenced an official programme of metrication that, as of 2012, had not been completed. The British metrication programme signalled the start of metrication programmes elsewhere in the Commonwealth, though India had started its programme in 1959, six years before the United Kingdom. South Africa (then not a member of the Commonwealth) set up a Metrication Advisory Board in 1967, New Zealand set up its Metric Advisory Board in 1969, Australia passed the Metric Conversion Act in 1970 and Canada appointed a Metrication Commission in 1971. Metrication in Australia, New Zealand and South Africa was essentially complete within a decade, while metrication in India and Canada is not complete. In addition the lakh and crore are still in widespread use in India, while in Canada the square foot is still widespread for commercial and residential advertisements and partially in construction because of the close trade relations with the United States, and the railways of Canada continue to measure their trackage in miles and speed limits in miles per hour because they also operate in the United States. Most other Commonwealth countries adopted the metric system during the 1970s.[51]

United States

In 1805 a Swiss geodesist Ferdinand Rudolph Hassler brought copies of the French metre and kilogram to the United States.[52] In 1830 the Congress decided to create uniform standards for length and weight in the United States.[53] Hassler was mandated to work out the new standards and proposed to adopt the metric system.[53] The Congress opted for the British Parlementiary Standard from 1758 and the Troy Pound of Great Britain from 1824 as length and weight standards.[53] Nevertheless the primary baseline of the US Coast Survey was measured in 1834 at Fire Island using four two-metre iron bars constructed after Hassler's specification in the United Kingdom and brought back in the United States in 1815.[54][55] All distances measured in the US National Geodetic Survey were referred to the metre.[56] In 1866 the United States Congress passed a bill making it lawful to use the metric system in the United States. The bill, which was permissive rather than mandatory in nature, defined the metric system in terms of customary units rather than with reference to the international prototype metre and kilogram.[57][58]:10–13 By 1893, the reference standards for customary units had become unreliable. Moreover, the United States, being a signatory of the Metre Convention was in possession of national prototype metres and kilograms that were calibrated against those in use elsewhere in the world. This led to the Mendenhall Order which redefined the customary units by referring to the national metric prototypes, but used the conversion factors of the 1866 act.[58]:16–20 In 1896 a bill that would make the metric system mandatory in the United States was presented to Congress. Of the 29 people who gave evidence before the congressional committee who were considering the bill, 23 were in favor of the bill, but six were against. Four of the six dissenters represented manufacturing interests and the other two the United States Revenue service. The grounds cited were the cost and inconvenience of the change-over. The bill was not enacted. Subsequent bills suffered a similar fate.[42]

Conversion process

The metric system was officially introduced in France in December 1799. In the 19th century, the metric system was adopted by almost all European countries: Portugal (1814);[35] Netherlands, Belgium and Luxembourg (1820); Switzerland (1835); Spain (1850s); Italy (1861); Romania (1864); Germany (1870, legally from 1 January 1872);[59] and Austria-Hungary (1876, but the law was adopted in 1871).[42] Thailand did not formally adopt the metric system until 1923, but the Royal Thai Survey Department used it for cadastral survey as early as 1896.[60] Denmark and Iceland adopted the metric system in 1907.

Chronology and status of conversion by country

Links in the country point to articles about metrication in that country.[61]

| Year official metrication process started[62][63][64] |

Country | Previous system of measure |

Status of metrication |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1795 | France | French | Complete |

| 1814 | Portugal[Note 1] | Portuguese | Complete |

| 1820 | Belgium | Various | Complete |

| 1820 | Netherlands | Dutch | Complete |

| 1848 | Chile | Spanish | Almost entirely complete |

| 1852[65] | Mexico | Variants of Spanish | Complete (some national and regional units are still in use and some United States customary units also in use in some industries) |

| 1852 | Spain | Spanish | Complete, however some pre-metric units are still in use: for land - ferrado, fanega, atahúlla and quiñón; for weight - libra and arroba; for liquids - cuartilla; for screen sizes - pulgada. |

| 1861 | Italy | Various | Complete |

| 1862[66] | Brazil | Portuguese | Complete, but some non-metric units are used for specific areas: rural land - alqueire; cattle weight - arroba; screen sizes - polegada; tyre pressure - libra-força por polegada quadrada, but referred by its English abbreviation: psi. |

| 1862 | Peru | Spanish | Almost entirely complete |

| 1863 | Uruguay | Spanish | Complete |

| 1864 | Romania | Romanian | Complete |

| 1868 | North German Confederation | Various | Complete |

| 1869 | South German states | Various | Complete |

| 1871 | Austria | Various | Complete |

| 1872[Note 2] | Germany | Various | Complete |

| 1873[67] | Serbia | Various | Complete |

| 1874 | Hungary | Hungarian | Complete |

| 1875 | Ottoman Empire/Turkey | Ottoman | Complete |

| 1875[68] | Norway | Norwegian | Complete |

| 1876 | Sweden | Swedish | Complete; the old unit of length mil, redefined in 1876 as 10 km, is however still in everyday use, including that fuel consumption for motor vehicles is always given as "liter per mil", both in everyday speech and in advertising; in some contexts, such as calculating cost of ownership of a vehicle ("milkostnad", i.e. cost per mil) and reimbursement for using a privately owned vehicle instead of a company car ("milersättning"), the mil is even still used in legal texts, in spite of officially not being a legal unit of length. |

| 1876 | Switzerland | Various | Complete |

| 1886 | Argentina | Spanish | Complete |

| 1886[69] | Finland | Finnish | Complete |

| 1899 | Paraguay | Variants of Spanish | Complete |

| 1907 | Denmark | Danish | Complete |

| 1907 | Iceland | Icelandic / Danish | Complete |

| 1907 | Philippines | Spanish, US customary and local | Almost entirely complete, English customary units still in use for body measurements |

| 1908 | Costa Rica | Spanish | Complete |

| 1912 | Dominican Republic | Spanish | Complete |

| 1918[70][71] | Russia | Russian | Complete |

| 1923[72][73] | Thailand | Various | Almost entirely complete |

| 1924[74] | Japan | Japanese | Complete, with continued informal use of the gō serving size, tsubo of floorspace, &c. |

| 1925 | China | Chinese | Almost entirely complete |

| 1929 | Estonia | Estonian | Complete |

| 1946 | Indonesia | Various | Almost entirely complete |

| 1948 | Israel | Ottoman | Complete |

| 1954 | India | Various | Complete |

| 1954 | Sudan | Various | Complete |

| 1959[75] | Greece | Ancient Greek | Complete |

| 1961 | South Korea | Korean | Complete, with continued informal use of the pyeong of floorspace |

| 1963 | Laos | Unknown | Complete |

| 1963 | Vietnam | Vietnamese | Complete |

| 1965[Note 3] | United Kingdom | Imperial | Partially complete |

| 1967 | Ireland | Imperial[Note 4] | Complete |

| 1967 | Pakistan | Imperial | Complete |

| 1969 | New Zealand | Imperial | Complete |

| 1970 | Australia | Imperial | Complete |

| 1971 | South Africa[Note 5] | Imperial | Complete |

| 1972 | Malaysia | Imperial and Malay | Partially complete, with some traditional wet markets and pasar pagi still using the Malay units. Imperial units are widely used such as size of the real estate are often denoted by square feet rather than square metres. |

| 1973[76] | Canada | Imperial | Almost entirely complete (Informal body measurements are referred to in Imperial units, and certain industries such as real estate, construction, and home appliances still use imperial measurements due to a high reliance on American Manufacturing.) [77] |

| 1975[Note 6][78] | United States of America | United States customary units | Some adoption[79] |

| 1975[80] | North Korea | Korean | Partially complete, with formal continued use of traditional units[81][82] |

| 1976[83] | Sri Lanka | Imperial | Almost entirely complete[84] |

| 1976 | Hong Kong | Imperial, Chinese | Almost entirely complete (wet markets still use the Chinese units or Imperial units, and real estates still use square foot as area measurement unit.) |

| 1984 | Taiwan | Taiwanese | Almost entirely complete (traditional wet markets and real estate still use Taiwanese units.) |

| 1992 | Macau | Imperial, Chinese (Also United States customary units) |

Almost entirely complete |

| 1998 | Jamaica | Imperial | Partially complete |

| 2005 | Saint Lucia | Imperial | Complete |

| Indeterminate | Liberia[Note 7] | Imperial[78] | Some adoption[Note 8][85] |

| 2011[Note 9][86] 2013[87] |

Burma (Myanmar) | Burmese, Imperial[78] | Some adoption[88] Announcement of full metrication, with technical assistance from the German National Metrology Institute[89] |

Notes

- ↑ Including Portuguese colonies, most of them now independent countries.

- ↑ Many German states, particularly those under French tutelage during the Napoleonic Wars (Rheinbund) adopted the metre 1806–15.

- ↑ Phased transition announced in 1965

- ↑ Old Irish units of measurement prior to 1807. See also Irish measure.

- ↑ Including South-West Africa, now Namibia

- ↑ First adopted in 1866, not enacted until Signing of the Metric Conversion Act in 1975

- ↑ See also Liberia measurement system.

- ↑ The Liberian government has begun transitioning from use of imperial units to the metric system. However, this change has been gradual, with government reports concurrently using both systems.

- ↑ In June 2011, the Burmese government's Ministry of Commerce began discussing proposals to reform the measurement system in Burma and adopt the metric system used by most of its trading partners.

There are three common ways that nations convert from traditional measurement systems to the metric system. The first is the quick, or "Big-Bang" route which was used by India in the 1960s and several other nations including Australia and New Zealand since then. The second way is to phase in units over time and progressively outlaw traditional units. This method, favoured by some industrial nations, is slower and generally less complete. The third way is to redefine traditional units in metric terms. This has been used successfully where traditional units were ill-defined and had regional variations.

The "Big-Bang" way is to simultaneously outlaw the use of pre-metric measurement, metricate, reissue all government publications and laws, and change education systems to metric. India's changeover lasted from 1 April 1960, when metric measurements became legal, to 1 April 1962, when all other systems were banned. The Indian model was extremely successful and was copied over much of the developing world.

The phase-in way is to pass a law permitting the use of metric units in parallel with traditional ones, followed by education of metric units, then progressively ban the use of the older measures. This has generally been a slow route to metric. The British Empire permitted the use of metric measures in 1873, but the changeover was not completed in most Commonwealth countries until the 1970s and 1980s when governments took an active role in metric conversion. Japan also followed this route and did not complete the changeover for 70 years. In the United Kingdom, the process is still incomplete. By law, loose goods sold with reference to units of quantity have to be weighed and sold using the metric system. In 2001, the EU directive 80/181/EEC stated that supplementary units (imperial units alongside metric including labelling on packages) would become illegal from the beginning of 2010. In September 2007,[19] a consultation process was started which resulted in the directive being modified to permit supplementary units to be used indefinitely.

The third method is to redefine traditional units in terms of metric values. These redefined "quasi-metric" units often stay in use long after metrication is said to have been completed. Resistance to metrication in post-revolutionary France convinced Napoleon to revert to mesures usuelles (usual measures), and, to some extent, the names remain throughout Europe. In 1814, Portugal adopted the metric system, but with the names of the units substituted by Portuguese traditional ones. In this system, the basic units were the mão-travessa (hand) = 1 decimetre (10 mão-travessas = 1 vara (yard) = 1 metre), the canada = 1 litre and the libra (pound) = 1 kilogram.[35] In the Netherlands, 500 g is informally referred to as a pond (pound) and 100 g as an ons (ounce), and in Germany and France, 500 g is informally referred to respectively as ein Pfund and une livre ("one pound").[90] In Denmark, the re-defined pund (500 g) is occasionally used, particularly among older people and (older) fruit growers, since these were originally paid according to the number of pounds of fruit produced. In Sweden and Norway, a mil (Scandinavian mile) is informally equal to 10 km, and this has continued to be the predominantly used unit in conversation when referring to geographical distances. In the 19th century, Switzerland had a non-metric system completely based on metric terms (e.g. 1 Fuss (foot) = 30 cm, 1 Zoll (inch) = 3 cm, 1 Linie (line) = 3 mm). In China, the jin now has a value of 500 g and the liang is 50 g.

It is difficult to judge the degree to which ordinary people change to using metric in their daily lives. In countries that have recently changed, older segments of the population tend to still use the older units. Also, local variations abound in which units are round metric quantities or not. In Canada, for example, ovens and cooking temperatures are usually measured in degrees Fahrenheit and Celsius. Except for in cases of import items, all recipes and packaging include both Celsius and Fahrenheit, so Canadians are typically comfortable with both systems of measurement. This extends to manufacturing, where companies are able to use both imperial and metric units, since the major export market is the US, but metric is required for both domestic use and for nearly all other exports. This may be due to the overwhelming influence of the neighbouring United States; similarly, many Canadians still often use non-metric measurements in day-to-day discussions of height and weight, though most driver's licences and other official government documents record weight and height only in metric (Saskatchewan driver licences, prior to the introduction of the current one-piece licence, indicated height in feet and inches but have switched to centimetres following the new licence format). In Canadian schools, however, metric is the standard, except when it comes up in recipes, where both are included, or in practical lessons involving measuring wood or other materials for manufacturing. In the United Kingdom, degrees Fahrenheit are seldom encountered (except when some people talk about hot summer weather), while other metric units are often used in conjunction with older measurements, and road signs use miles rather than kilometres. Another example is "hard" and "soft" metric. Canada converted liquid dairy products to litre, 500 mL, and 250 mL sizes, which caused some complaining at the time of the conversion, as a litre of milk is slightly over 35 imperial fluid ounces, while the former imperial quart used in Canada was 40 ounces. This is an example of a "hard" metric conversion. Conversely, butter in Canada is sold primarily in a 454 g package, which converts to one Imperial pound. This is considered a "soft" metric conversion.

Exceptions

As of 2015, the metric system officially predominates in most countries of the world; some traditional units, however, are still used in many places in specific industries. For example:

- Photo and video cameras are standardized to mount to tripods using 1⁄4-20 and 3⁄8-16 screws, which are dimensioned in inches, as per ISO 1222:2010.[91]

- Automobile tyre pressure is commonly measured in units of psi in several countries including Brazil, Peru, Argentina, Australia, and Chile, the UK and the US.

- Automotive engine power is usually measured in horsepower (rather than in kilowatts) in Russia, most other ex-USSR countries and German-speaking countries (note that this is typically "metric horsepower" rather than imperial horsepower), although in the EU from 2010 the horsepower is permitted only as a supplementary unit.[92]

- In Hong Kong, traditional Chinese and British imperial units are normally used instead of metric units in particular types of trade.

- Construction workers in Northern Europe often refer to planks and nails by their old inch-based names.

- The length of small sail boats is often given in feet in popular conversation.

- Office space is often rented in traditional units, such as square feet in Hong Kong and India, tsubo/pyeong/"ping" in Japan, Korea, and Taiwan.

- In plumbing, some pipes and pipe threads are still designated in inch sizes due to historic international acceptance of particular sequences of pipe sizes and pipe threads, such as BSP / ISO 7 / EN 10226 threads.

- In the United Kingdom and some Commonwealth countries, temperatures of domestic gas ovens are often specified using gas marks.[93][94] Similarly, older French ovens and recipes book often use a scale based on the Fahrenheit scale: "Thermostat" (abbreviated "Th"), where Thermostat 1 equals 100 °F for conventional ovens, increasing by 50 °F for each whole number along the scale.[95]

- Automotive and bicycle wheel diameters are still usually but not always set as whole inch measurements (although tyre widths are measured in millimetres).

- Dots per inch and pixels per inch continue to be used in describing graphical resolution in the computer and printing industry.

- Thread count is frequently measured in "threads per inch" or "ends per inch".

- Television and monitor screen diagonals are still commonly cited in inches in many countries; however, in countries such as Australia, France and South Africa, centimetres are often used for television sets, whereas CRT computer monitors and all LCD monitors are measured in inches.

- Many large format computer printers, commonly known as plotters, have carriage widths measured in inches. Common widths are 24 in (610 mm), 36 in (910 mm), 44 in (1,100 mm) and 60 in (1,500 mm). While metric media sizes are often quoted (e.g. A0, A1), rolls of film, plain paper or photographic paper are normally sold in these widths, giving rise to wastage when they are trimmed. Rolls lengths are variously quoted in feet or metres.

- In the electronic industry, the dominant spacing for components is based on intervals of 1⁄10 in (2.54 mm), and a change would lead to compatibility issues, e.g., for connectors.

- Within the mechanical industry, inch-based spare parts can occasionally be kept, e.g., to service American or pre-World War II machines, but at maintenance, screws may be exchanged to metric thread.

- In Ireland, the only legal exception to the metrication process was the pint (redefined as 570ml) in bars, pubs, and clubs (although alcohol sold in any other location is in metric units (usually 330 ml (bottled beer), 500 ml (canned beer), 750 ml (wine), or 1 L or 700 ml (spirits))).

- In Australia, a pint of beer was redefined to 570 ml (see Australian beer glasses).

- In both metric and non-metric countries, racing bicycle frames are generally measured in centimetres, while mountain bicycle and other frames are measured in either or both.

- In the sport of surfing, surfboards are usually designed, constructed, and sold in feet and inches.

- In Spain and former colonies i.e. Americas and Philippines certain pre-metric units are still used, e.g., the quiñón for land measurement in the Philippines, the fanega, ferrado and atahúlla to name three used in Spain and other former possessions.

- The pulgada (inch) is 23 mm, 2 mm shorter than the English inch.

- In many long-time metric countries, when non-metric units are used, it is often to give rough estimates in a short form, while accurate measures always are metric, e.g., "6 feet" may feel less exact and shorter to say than "1.8 metres" or "180 cm". Measurement tools for inches are generally rare to find there, only on the other side of some carpenter's rulers, and may present a variation between national legacy inches and British/US inches, easily causing significant measurement errors if used.

- The Imperial gallon is used as a unit of measure for fuel in Anguilla, Antigua and Barbuda, Burma, the Cayman Islands, Dominica, Grenada, Montserrat, St Kitts and Nevis and St Vincent and the Grenadines. In the United Kingdom fuel efficiency is officially recorded in miles per imperial gallon although fuel is sold in litres.

- The US gallon is used in the Bahamas, Belize, British Virgin Islands, Colombia, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, Liberia, Peru, Turks and Caicos Islands, and the US, especially for pricing.

- In Latin America, as SI units are standard, litres are used as well, e.g., often regarding fuel economy (km per litre), and the Spanish word galón may occasionally refer to a portable fuel container, often 5-20 L.

- Road distances and speed limits are still displayed in miles and miles per hour respectively in the USA, UK, Burma, and various Caribbean nations.[96]

In some countries (such as Antigua and Barbuda, see above), the transition is still in progress. The Caribbean island nation of Saint Lucia announced metrication programmes in 2005 to be compatible with CARICOM.[97]

United Kingdom

In the United Kingdom, some of the population continue to resist metrication to varying degrees. The traditional imperial measures are preferred by a majority and continue to have widespread use in some applications.[98][99] The metric system is used by most businesses,[100] and is used for most trade transactions. Metric units must be used for certain trading activities (selling by weight or measure for example), although imperial units may continue to be displayed in parallel.[101]

British law has enacted the provisions of European Union directive 80/181/EEC, which catalogues the units of measure that may be used for "economic, public health, public safety and administrative purposes".[102] These units consist of the recommendations of the General Conference on Weights and Measures,[49] supplemented by some additional units of measure that may be used for specified purposes.[103] Metric units could be legally used for trading purposes for nearly a century before metrication efforts began in earnest. The government had been making preparations for the conversion of the Imperial unit since the 1862 Select Committee on Weights and Measures recommended the conversion[104] and the Weights and Measures Act of 1864 and the Weights and Measures (Metric System) Act of 1896 legalised the metric system.[105] In 1965, with lobbying from British industries and the prospects of joining the Common Market, the government set a 10-year target for full conversion, and created the Metrication Board in 1969. Metrication did occur in some areas during this time period, including the re-surveying of Ordnance Survey maps in 1970, decimalisation of the currency in 1971, and teaching the metric system in schools. No plans were made to make the use of the metric system compulsory, and the Metrication Board was abolished in 1980 following a change in government.[106]

The United Kingdom avoided having to comply with the 1989 European Units of Measurement Directive (89/617/EEC), which required all member states to make the metric system compulsory, by negotiating derogations (delayed switchovers), including for miles on road signs and for pints for draught beer, cider, and milk sales.[107]

Following the United Kingdom's referendum to exit the European Union, retailers have begun to request to go back to using Imperial Units, with some reverting without permission. A poll following the EU vote also found that 45% of Britons sought to revert to selling produce in Imperial Units.[108]

In popular conversation, the stone unit is widely used for measuring a person's weight and feet and inches for height.

United States and Canada

Over time, the metric system has influenced the United States through international trade and standardisation. The use of the metric system was made legal as a system of measurement in 1866[109] and the United States was a founding member of the International Bureau of Weights and Measures in 1875.[110] The system was officially adopted by the federal government in 1975 for use in the military and government agencies, and as preferred system for trade and commerce.[111] It has remained voluntary for federal and state road signage to use metric units, despite attempts in the 1990s to make it a requirement.[112]

A 1992 amendment to the Fair Packaging and Labeling Act (FPLA), which took effect in 1994, required labels on federally regulated "consumer commodities"[113] to include both metric and US customary units. As of 2013, all but one US state (New York) have passed laws permitting metric-only labels for the products they regulate.[114] Likewise, Canada also legally allows for dual labelling of goods provided that the metric unit is listed first and that there is a distinction of whether a liquid measure is a US or a Canadian (Imperial) unit.[115]

Today, the American public and much of the private business and industry still use US customary units despite many years of informal or optional metrication.[116] At least two states, Kentucky and California, have even moved towards demetrication of highway construction projects.[117][118][119]

Air and sea transportation

Air and sea transportation commonly use the nautical mile. This is about one minute of arc of latitude along any meridian arc and it is precisely defined as 1852 metres (about 1.151 statute miles). It is not an SI unit (although it is accepted for use in the SI by the BIPM). The prime unit of speed or velocity for maritime and air navigation remains the knot (nautical mile per hour).

The prime unit of measure for aviation (altitude, or flight level) is usually estimated based on air pressure values, and in many countries, it is still described in nominal feet, although many others employ nominal metres. The policies of the International Civil Aviation Organisation (ICAO) relating to measurement are:

- there should be a single system of units throughout the world

- the single system should be the SI

- the use of the foot for altitude is a permitted variation.

Consistent with ICAO policy, aviation has undergone a significant amount of metrication over the years. For example, runway lengths are usually given in metres. The United States metricated the data interchange format (METAR) for temperature reports in 1996.[120] Metrication is also gradually taking place in cargo weights and dimensions and in fuel volumes and weights.

In some countries like China, ex Soviet countries and Russia, the metric system is used in aviation (whereby in Russia altitudes above the transition level are given in feet)[121][122]. Sailplanes use the metric system in many European countries.

Accidents and incidents

Confusion over units during the process of metrication can sometimes lead to accidents. One of the most notable examples was during metrication in Canada. In 1983, an Air Canada Boeing 767, nicknamed the "Gimli Glider" following the incident, ran out of fuel in midflight. The incident was caused, in a large part, by the confusion over the conversion between litres, kilograms, and pounds, resulting in the aircraft receiving 22,300 pounds of fuel instead of the required 22,300 kg.[123]

While not strictly an example of national metrication, the use of two different systems was a contributing factor in the loss of the Mars Climate Orbiter in 1999. The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) specified metric units in the contract. NASA and other organisations worked in metric units, but one subcontractor, Lockheed Martin, provided thruster performance data to the team in pound force-seconds instead of newton-seconds. The spacecraft was intended to orbit Mars at about 150 kilometres (93 mi) in altitude, but the incorrect data meant that it descended to about 57 kilometres (35 mi). As a result, it burned up in the Martian atmosphere.[124]

On 25 September 2009, the British Department for Transport published a draft version of legislation to amend its road signs legislation[125] for comment. Among the proposed changes was an amendment to existing legislation to make dual-unit height and width warning and restriction signs mandatory. This was justified in Paragraph 53 of the Impact Analysis[126] by the text "... Based on records from Network Rail's incident logs since April 2008, approximately 10 to 12 percent of bridge strikes involved foreign lorries. This is disproportionately high in terms of the number of foreign lorries on the road network." This proposal was shelved with the change of government in 2010, though many bridges are now signed both ways. The latest signage guidance consultation has proposed this once again.

See also

- Anti-metrication

- Change management, a field studying how changes can be efficiently implemented in modern communities

- Conversion of units

- Language reform

- Metric clothes sizes (EN 13402)

- French units of measurement

- Metrication in Chile

- Metrication in the United Kingdom

- Metrication in the United States

- Metrication in Canada

- Plan for Establishing Uniformity in the Coinage, Weights, and Measures of the United States

- Preferred numbers

- Spread of the Latin script

References

- ↑ "Maintenance Required Indicator" (PDF). Techinfo.honda.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 24 November 2014.

- ↑ "Metrication". Oxford English Dictionary (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. September 2005. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ "Appendix G – Weights and Measures". The World Factbook. CIA. 2006. Retrieved 8 August 2006.

- ↑ "Gov't Pledges Commitment to Adopt Metric System | Liberian Observer". www.liberianobserver.com. Retrieved 2018-08-25.

- ↑ https://www.nationsencyclopedia.com/Americas/Belize.html

- ↑ Kuhn, Markus (2 October 2017). "USENET Metric System FAQ". Retrieved 12 October 2017.

- 1 2 Kelly, Jon (21 December 2011). "Will British people ever think in metric?". BBC.

- 1 2 3 Alder, Ken (2002). The Measure of all Things – The Seven-Year-Odyssey that Transformed the World. London: Abacus. ISBN 978-0-349-11507-8.

- ↑ Kohler, Nicholas. "Metrication in Myanmar".

- ↑ "Myanmar to adopt metric system". www.elevenmyanmar.com. Eleven Media Group. 10 October 2013. Retrieved 12 October 2013.

- ↑ "Metric usage and metrication in other countries". US Metric Association. 2009. Archived from the original on 21 February 1999. Retrieved 23 May 2009.

- ↑ "Introduction of the metric system and the prices of petroleum products". Washington DC, United States: Sierra Leone Embassy. 9 May 2011. Archived from the original on 18 May 2011. Retrieved 9 May 2011.

- ↑ "Metric Act of 1866" (PDF). Metric Program, Weights and Measures Division, United States National Institute of Standards, Technology and Technology. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 May 2010. Retrieved 10 November 2009.

"U.S. Metric System (SI) Legal Resources". Metric Program, Weights and Measures Division, United States National Institute of Standards, Technology and Technology. Archived from the original on 1 August 2009. Retrieved 11 November 2009. - ↑ Howard B. Bradley, ed. (1987). Petroleum Engineering Handbook. pp. 1–69. ISBN 1555630103.

- ↑ Warwick Cairns (2007). About the Size of It. Pan Macmillan. p. 145. ISBN 978-0-230-01628-6.

- ↑ "Finance minister outlines metrication plans, goals and timetable". Antigua Observer. 18 October 2011. Retrieved 12 November 2011.

- ↑ "St Lucia begins drive to implement metric system to catch up with region". The Jamaica Observer. Associated Press. 2005. Archived from the original on 18 October 2007. Retrieved 5 November 2007.

- ↑ "Department for Transport statement on metric road signs". British Weights and Measures Association. 2002. Retrieved 23 May 2009.

- 1 2 3 "EU gives up on 'metric Britain". BBC News. 11 September 2007. Retrieved 23 May 2009.

- ↑ "Ireland goes metric - fast". The Independent. Archived from the original on 29 October 2014. Retrieved 24 November 2014.

- ↑ "Metric Moon". NASA. 2007. Retrieved 6 April 2010.

- ↑ Thomas McGreevy, Peter Cunningham (1995). The Basis of Measurement: Historical Aspects. Picton Publishing. ISBN 0-948251-82-4.

- ↑ Witold Kula (1986). "For all peoples; for all time". Measures and Men. Richard Szreter (trans.). Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-05446-0.

- ↑ O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F. (January 2004), "Metrication", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews .

- ↑ Reproduction (33 MB):John Wilkins (1668). "VII". An Essay towards a Real Character and a Philosophical Language (PDF). The Royal Society. pp. 190–194. Retrieved 6 March 2011.

- ↑ "An ESSAY Towards a REAL CHARACTER, And a PHILOSOPHICAL LANGUAGE" (PDF). Metricationmatters.com. Retrieved 24 November 2014.

- ↑ O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F. (January 2004), "Metrication", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews .

- ↑ Jefferson, Thomas (4 July 1790). "Plan for Establishing Uniformity in the Coinage, Weights, and Measures of the United States Communicated to the House of Representatives, July 13, 1790". New York.

- ↑ Linklater, Andro (2002). Measuring America: How an Untamed Wilderness Shaped the United States and Fulfilled the Promise of Democracy. Walker & Co. ISBN 978-0-8027-1396-4.

- ↑ Denis Février. "Un historique du mètre" (in French). Ministère de l'Economie, des Finances et de l'Industrie. Retrieved 2011-03-10.

- ↑ Hallock, William; Wade, Herbert T (1906). "Outlines of the evolution of weights and measures and the metric system". London: The Macmillan Company. pp. 66–69.

- ↑ "History of measurement". Laboratoire national de métrologie et d'essais (LNE) (Métrologie française). Retrieved 6 February 2011.

- 1 2 Crease, Robert P. (2011). World in the Balance: The Historical Quest for an Absolute System of Measurement. New York & London: W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 124 & 164. ISBN 978-0-393-34354-0.

- ↑ Crease (2011) refers to: Kennelly, Arthur E. (1928). Vestiges of Pre-metric Weights and Measures Persisting in Metric-system Europe, 1926–27. New York: Macmillan. p. vii.

- 1 2 3 Fátima Paixão; Fátima Regina Jorge (2006). "Success and constraints in adoption of the metric system in Portugal" (PDF). The Global and the Local: History of Science and the Cultural Integration of Europe. Retrieved 24 November 2014.

- ↑ Jacob de Gelder (1824). Allereerste Gronden der Cijferkunst [Introduction to Numeracy] (in Dutch). 's Gravenhage and Amsterdam: de Gebroeders van Cleef. pp. 155–157. Retrieved 2011-03-02.

- 1 2 "Amtliche Maßeinheiten in Europa 1842" [Official units of measure in Europe 1842] (in German). Retrieved 2011-03-26Text version of Malaisé's book

- ↑ Ferdinand Malaisé (1842). Theoretisch-practischer Unterricht im Rechnen [Theoretical and practical instruction in arithmetic] (in German). München. pp. 307–322. Retrieved 2011-03-26.

- ↑ Heinrich Grebenau (1870). "Tabellen zur Umwandlung des bayerischen Masses und Gewichtes in metrisches Maß und Gewicht und umgekehrt" [Conversion tables for converting between Bavarian units of measure and metric units] (in German). Munich. Retrieved 2011-03-07.

- ↑ Silke Parras (2006). Der Marstall des Schlosses Anholt (16. bis 18. Jahrhundert) – Quellen und Materialien zur Geschichte der Pferdehaltung im Münsterland [The stables of the castle Anholt (16th to 18th century) – sources and materials on the history of horses in Munster] (PDF) (Dr. med. vet thesis) (in German). Tierärztliche Hochschule Hannover [Hannover veterinary university]. pp. 14–20. Retrieved 2011-03-07.

- ↑ Meyer-Stoll, Cornelia (2010). Die Mass-und Gewichtsreformen in Deutschland im 19. Jahrhundert unter besonderer Berucksichtigung der Rolle Carl August Steinheils und der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften [The weights and measure reforms in Germany in the 19th century with special reference to Rolle Carl August and the Bavarian Academy of Sciences] (in German). Munich: Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften [Bavarian Academy of Sciences]. p. 129. ISBN 978-3-7696-0124-4.

- 1 2 3 W Leconte Stephens (March 1904). "The Metric System – Shall it be compulsory?". Popular Science Monthly: 394–405. Retrieved 2011-05-17.

- ↑ "Pfund" (in German). Universal-Lexikon. 2010. Retrieved 17 May 2011.

- 1 2 3 Maria Teresa Borgato (6–9 September 2006). "The first applications of the metric system in Italy" (PDF). The Global and the Local:The History of Science and the Cultural Integration of Europe. Proceedings of the 2nd ICESHS. Cracow, Poland: The Press of the Polish Academy of Arts and Sciences. Retrieved 2011-03-17.

- 1 2 Loidi, Juan Navarro; Saenz, Pilar Merino (6–9 September 2006). "The units of length in the Spanish treatises of military engineering" (PDF). The Global and the Local: The History of Science and the Cultural Integration of Europe. Proceedings of the 2nd ICESHS. Cracow, Poland: The Press of the Polish Academy of Arts and Sciences. Retrieved 2011-03-17.

- ↑ Lebon, Ernest (1846-1922) Auteur du texte (1899). Histoire abrégée de l'astronomie / par Ernest Lebon,... Paris: Gauthier-Villars. p. 171.

- ↑ "Industry and community – Key dates". United Kingdom Parliament. Retrieved 2011-03-28.

- 1 2 3 Frederik Hyttel (May 2009). Working man's pint – An investigation of the implementation of the metric system in Britain 1851–1979 (PDF) (BA thesis). Bath, United Kingdom: Bath Spa University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 29 March 2011.

- 1 2 International Bureau of Weights and Measures (2006), The International System of Units (SI) (PDF) (8th ed.), ISBN 92-822-2213-6, archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-08-14

- ↑ Jabbour, Z.J.; Yaniv, S.L. (2001). "The Kilogram and Measurements of Mass and Force" (PDF). J. Res. Natl. Inst. Stand. Technol. National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST. 106 (1): 25–46. doi:10.6028/jres.106.003. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 June 2011. Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- ↑ "Metrication status and history". United States Metrication Association. 2009. Archived from the original on 2010-07-24. Retrieved 2011-05-19.

- ↑ "e-expo: Ferdinand Rudolf Hassler". www.f-r-hassler.ch. Retrieved 2017-12-19.

- 1 2 3 "e-expo: Ferdinand Rudolf Hassler". www.f-r-hassler.ch. Retrieved 2017-12-19.

- ↑ "NIST Special Publication 1068 Ferdinand Rudolph Hassler (1770-1843) A Twenty Year Retrospective, 1987-2007" (PDF). NIST. pp. 51–52. Retrieved 2017-11-27.

- ↑ "e-expo: Ferdinand Rudolf Hassler". www.f-r-hassler.ch. Retrieved 2017-12-19.

- ↑ Clarke, Alexander Ross; James, Henry (1873-01-01). "XIII. Results of the comparisons of the standards of length of England, Austria, Spain, United States, Cape of Good Hope, and of a second Russian standard, made at the Ordnance Survey Office, Southampton. With a preface and notes on the Greek and Egyptian measures of length by Sir Henry James". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 163: 445–469. doi:10.1098/rstl.1873.0014. ISSN 0261-0523.

- ↑ 29th Congress of the United States, Session 1 (May 13, 1866). "H.R. 596, An Act to authorize the use of the metric system of weights and measures". Archived from the original on July 5, 2015. Retrieved 2011-05-19.

- 1 2 Barbrow, Louis E.; Judson, Lewis V. (1976). Weights and Measures Standards of the United States: A brief history. NIST. Archived from the original on 2011-06-03. Retrieved 2011-05-19.

- ↑ Andreas Dreizler; et al. (20 April 2009). "Metrologie" (PDF) (in German). Technische Universität Darmstaft. Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- ↑ Giblin, R. W. (2008) [1908]. "Royal Survey Work.". In Wright, Arnold; Breakspear, Oliver T. Twentieth century impressions of Siam (65.3 MB). London&c: Lloyds Greater Britain Publishing Company. p. 126. Retrieved 28 January 2012.

It so happens that 40 metres or 4,000 centimetres are equal to one sen, which is the Siamese unit of linear measurement.

- ↑ AD Dunn (1969). "Notes on the standardization of paper sizes" (PDF). Ottawa. p. 11.

- ↑ Page, Chester H; Vigoureux, Paul, eds. (20 May 1975). The International Bureau of Weights and Measures 1875 - 1975: NBS Special Publication 420. Washington, D.C.: National Bureau of Standards. p. 244.

- ↑ Zupko, Ronald Edward (1990). Revolution in Measurement – Western European Weights and Measures Since the Age of Science. Memoirs of the American Philosophical Society. 186. pp. 242–245. ISBN 0-87169-186-8. Retrieved 21 April 2012.

- ↑ The Metric versus the English System of Weights and Measures. National Industrial Conference Board. October 1921. pp. 12–13. Research Report Number 42. Retrieved 1 June 2013.

- ↑ "Metrication in Mexico". Lamar.colostate.edu. Archived from the original on 31 August 2012. Retrieved 24 November 2014.

- ↑ "Histórico do Inmetro". Inmetro.gov.br. Retrieved 24 November 2014.

- ↑ "History". Beograd, Serbia: Misitry of finance and economy: Directorate of Measures and Precious Metals. Retrieved 28 March 2013.

- ↑ "Kapittel 4 : Internasjonale avtaler" (PDF). Regjeringen.no. Retrieved 24 November 2014.

- ↑ "Metric usage and metrication in other countries". Lamar.colostate.edu. Archived from the original on 21 February 1999. Retrieved 24 November 2014.

- ↑ "Metric". ru:Собрание узаконений РСФСР (in Russian) (66): 725. 1918.

- ↑ Настольный Советский Календарь [Desk Soviet Calendar] (in Russian). The New International Publishing, New York. 1920. p. 8.

- ↑ "History of weights and measures in Thailand.htm". Northern Weights and Measures Center (Thailand). April 2004. Retrieved 26 September 2011.

..."Weights and Measures Act, B.E. 2466" [1923 A.D.] .... [superseded by ] "Weights and Measures Act, B.E. 2542" ... Government Gazette, Royal Decree Version, Volume 116, Part 29 a, dated 21 April 1999 ... effective since 18 October 1999

- ↑ ประวัติชั่งตวงวัดไทย (in Thai). Northern Weights and Measures Center (Thailand). April 2004. Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- ↑ Mitsuo, Tamano (July 1971), "Japan's Transition to the Metric System", US Metric Study Interim Report, No. 3: Commercial Weights and Measures, National Bureau of Standards Special Publication 345-3, Washington: US Department of Commerce, pp. 97–98 .

- ↑ "ΕΛΛΗΝΙΚΗ ΔΗΜΟΚΡΑΤΙΑ ΥΠΟΥΡΓΕΙΟ ΕΣΩΤΕΡΙΚΩΝ ΤΜΗΜΑ ΕΚΔΟΣΕΩΝ ΚΑΙ ΓΡΑΜΜΑΤΕΙΑΚΗΣ-ΛΟΓΙΣΤΙΚΗΣ ΕΞΥΠΗΡΕΤΗΣΗΣ : ΔΙΑΡΚΗΣ ΚΩΔΙΚΑΣ ΝΟΜΟΘΕΣΙΑΣ : ΙΔΡΥΤΗΣ – ΔΩΡΗΤΗΣ" (DOC). E-themis.gov.gr. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ↑ "Weights and Measures Act". Chapter 36 Section 7. Minister of Justice. 1985. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- ↑ Dr. Natarajan Ganapathy (2009). "Metric Conversion". Science & Medicine. The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved 26 May 2018.

- 1 2 3 "CIA The World Factbook". Appendix G: Weights and Measures. US Central Intelligence Agency. 2010. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- ↑ "FAQ: Frequently Asked Questions about the metric system:". U.S. Metric Association. 3 August 2012. Archived from the original on 4 October 2012. Retrieved 29 August 2012.

- ↑ "DPR Korea", Official site, Asia–Pacific Legal Metrology Forum, 2015 .

- ↑ "The Law of the Democratic People's Republic of Korea on Metrology" (PDF), No. 484-112, Pyongyang: Supreme People's Assembly of the DPRK, 3 February 1993 . (in Korean) & (in English)

- ↑ "North Korea: Summary", The Economist Intelligence Unit, London: The Economist Group, 10 February 2017 .

- ↑ "Numerical Metric Conversion" (PDF). Commonlii.org. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ↑ "-- Letters". Archives.dailynews.lk. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ↑ Dr. Michael D. Wilcox, Jr. Department of Agricultural Economics University of Tennessee (2008). "Reforming Cocoa and Coffee Marketing in Liberia" (PDF). Presentation and Policy Brief. University of Tennessee. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 June 2010. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- ↑ Ko Ko Gyi (18–24 July 2011). "Ditch the viss, govt urges traders". The Myanmar Times. Archived from the original on 28 May 2013. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- ↑ "Myanmar to adopt metric system". Eleven Media Group. 10 October 2013. Archived from the original on 20 December 2013. Retrieved 20 April 2015.

- ↑ Htar Htar Khin (20 February 2012). "Workshop to mull new weight and measurement standards". The Myanmar Times. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- ↑ Kohler, Nicholas (3 March 2014). "Metrication in Myanmar". Mizzima News. Archived from the original on 16 December 2014. Retrieved 20 April 2015.

- ↑ Hubert Fontaine. "Confiture de rhubarbe" (in French). Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 5 November 2007. "1 zeste de citron par livre (500g) de rhubarbe"

- ↑ ANSI, American National Standards Institute. "Find Standards using keywords and publication number". Webstore.ansi.org. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ↑ "Directive 2009/3/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 March 2009" (PDF). Official Journal of the European Union. Retrieved 5 February 2015.

- ↑ "Conversion Guides". BBC Good Food. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- ↑ "Cooking Conversion Charts". The Guardian. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- ↑ "Oven Temperatures". Practically Edible. 5 October 2007. Archived from the original on 30 June 2010. Retrieved 20 June 2010.

- ↑ ChartsBin. "Road Distance and Speed Units by Country". ChartsBin. Retrieved 24 November 2014.

- ↑ "St Lucia moving to metric system". Caribbean Net News. 2005. Archived from the original on 29 November 2005. Retrieved 27 August 2006.

- ↑ Jon Kelly (21 December 2011). "Will British people ever think in metric?". News Magazine. The BBC. Retrieved 24 February 2012.

...but today the British remain unique in Europe by holding onto imperial weights and measures. ...the persistent British preference for imperial over metric is particularly noteworthy...

- ↑ Melanie McDonagh (10 May 2007). "In the merry old land of lb and oz". The Times.

A survey from the British Weights and Measures Association, admittedly a partial source, suggested that 80 per cent of people prefer imperial to metric and 70 per cent, including, remarkably, 18- to 24-year-olds, can make sense of weights only in imperial measurements.

- ↑ "Final Report of the Metrication Board (1980)" (PDF). London: Department of Trade and Industry Consumer and Competition Policy Directorate. para 1.6 & 1.10. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 May 2013. Retrieved 29 June 2012.

- ↑ "Weights and measures legislation – hallmarking and metrication". Business Link. UK Government. Retrieved 24 February 2015.

- ↑ "Weights and Measures Report 1995 – 2008" (PDF). National Weights and Measures Laboratory. Retrieved 24 November 2014.

- ↑ The Council of the European Communities (9 February 2000). "Council Directive 80/181/EEC of 20 December 1979 on the approximation of the laws of the Member States relating to Unit of measurement and on the repeal of Directive 71/354/EEC". Retrieved 28 October 2011.

- ↑ "Report (1862) from the Select Committee on Weights and Measures" (PDF). Department of Trade and Industry, United Kingdom. 1862. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 June 2009. Retrieved 23 May 2009.

- ↑ "Metrication Timeline". UK Metric Association. 2008. Archived from the original on 8 June 2009. Retrieved 23 May 2009.

- ↑ Jim Humble. "Historical perspectives by the last Director of the UK Metrication Board". UK Metric Association. Archived from the original on 15 September 2008. Retrieved 27 May 2009.

- ↑ The Units of Measurement Regulations 1995. Statutory Instrument 1995 No. 1804. United Kingdom. 1995. ISBN 0-11-053334-8. Retrieved 27 August 2006.

- ↑ "After Brexit, some Brits want to ditch the metric system, too". Washington Post. Retrieved 4 October 2016.

- ↑ "Metric Act of 1866". Lamar.colostate.edu. Archived from the original on 10 October 2014. Retrieved 24 November 2014.

- ↑ "Metric Convention of 1875". Lamar.colostate.edu. Archived from the original on 1 March 2005. Retrieved 24 November 2014.

- ↑ "Metric Conversion Act of 1975". Lamar.colostate.edu. Archived from the original on 14 July 2003. Retrieved 24 November 2014.

- ↑ "National Highway System Designation Act of 1995". Lamar.colostate.edu. Archived from the original on 14 December 2002. Retrieved 24 November 2014.

- ↑ "Fair Packaging and Labeling Act". Lamar.colostate.edu. Archived from the original on 14 December 2002. Retrieved 24 November 2014.

- ↑ "U.S. Metric Association (USMA)". Lamar.colostate.edu. Archived from the original on 20 December 2012. Retrieved 24 November 2014.

- ↑ Chapter 2 – Basic Labelling Requirements. Canadian Food Inspection Agency. pp. (also available in French). Retrieved 16 May 2007.

- ↑ "Waits and Measures". Mother Jones. Retrieved 24 November 2014.

- ↑ Archived 24 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Metric to U.S. Customary Units (English) Transition" (PDF). Dot.ca.gov. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

- ↑ Richard D. Land, Chief Engineer (16 June 2006). Declaration of Units of Measure—"Metric" or "English" Project (PDF). State of California, Department of Transportation. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

- ↑ "Frequently Asked Questions about METAR/SPECI and TAF". National Weather Service METAR/TAF Information. Retrieved 21 August 2009.

- ↑ "Aviation's Crazy, Mixed Up Units of Measure - AeroSavvy". 5 September 2014.

- ↑ Why doesn't the aviation industry use SI units?, Aviation StackExchange

- ↑ Merran Williams (July–August 2003). The 156-tonne GIMLI GLIDER (PDF). Flight Safety Australia. pp. 22, 25. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 November 2007. Retrieved 5 November 2007.

- ↑ "NASA's metric confusion caused Mars orbiter loss". CNN. 30 September 1999. Retrieved 24 May 2013.

- ↑ "The Traffic Signs (Amendment) Regulations and General Directions 2010 (Draft)" (PDF). Department for Transport. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 December 2009. Retrieved 23 March 2011.

- ↑ "Impact Assessment of the Traffic Signs (Amendment) Regulations and General Directions 2010 and of the Traffic Signs (Temporary Obstructions) (Amendment) Regulations 2010" (PDF). Department for Transport. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 December 2009. Retrieved 23 March 2011.