Maunder Minimum

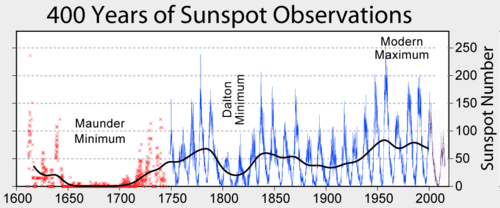

The Maunder Minimum, also known as the "prolonged sunspot minimum", is the name used for the period around 1645 to 1715 during which sunspots became exceedingly rare, as was then noted by solar observers.

The term was introduced after John A. Eddy[1] published a landmark 1976 paper in Science.[2] Astronomers before Eddy had also named the period after the solar astronomers Annie Russell Maunder (1868–1947) and her husband, Edward Walter Maunder (1851–1928), who studied how sunspot latitudes changed with time.[3] The period which the spouses examined included the second half of the 17th century.

Two papers were published in Edward Maunder's name in 1890[4] and 1894,[5] and he cited earlier papers written by Gustav Spörer.[6] Because Annie Maunder had not received a university degree, due to restrictions at the time, her contribution was not then publicly recognized.[7]

Spörer noted that, during a 28-year period (1672–1699) within the Maunder Minimum, observations revealed fewer than 50 sunspots.

This contrasts with the typical 40000 – 50000 sunspots seen in modern times (over similar 25 year sampling).[8]

Like the Dalton Minimum and the Spörer Minimum, the Maunder Minimum coincided with a period of lower-than-average European temperatures.

Sunspot observations

The Maunder Minimum occurred between 1645 and 1715 when very few sunspots were observed.[9] This was not due to a lack of observations; during the 17th century, Giovanni Domenico Cassini carried out a systematic program of solar observations at the Observatoire de Paris, thanks to the astronomers Jean Picard and Philippe de La Hire. Johannes Hevelius also performed observations on his own. The total numbers of sunspots (but not Wolf numbers) in different years were as follows:

| Year | Sunspots |

|---|---|

| 1610 | 9 |

| 1620 | 6 |

| 1630 | 9 |

| 1640 | 0 |

| 1650 | 3 |

| 1660 | Some sunspots (20<) reported by Jan Heweliusz in Machina Coelestis |

| 1670 | 0 |

| 1680 | 1 huge sunspot observed by Giovanni Domenico Cassini |

During the Maunder Minimum enough sunspots were sighted so that 11-year cycles could be extrapolated from the count.

The maxima occurred in 1676–1677, 1684, 1695, 1705 and 1718.

The sunspot activity was then concentrated in the southern hemisphere of the Sun, except for the last cycle when the sunspots appeared in the northern hemisphere, too.

According to Spörer's law, at the start of a cycle, spots appear at ever lower latitudes until they average at about latitude 15° at solar maximum.

The average then continues to drift lower to about 7° and after that, while spots of the old cycle fade, new cycle spots start appearing again at high latitudes.

The visibility of these spots is also affected by the velocity of the Sun's surface rotation at various latitudes:

| Solar latitude | Rotation period (days) |

|---|---|

| 0° | 24.7 |

| 35° | 26.7 |

| 40° | 28.0 |

| 75° | 33.0 |

Visibility is somewhat affected by observations being done from the ecliptic. The ecliptic is inclined 7° from the plane of the Sun's equator (latitude 0°).

Little Ice Age

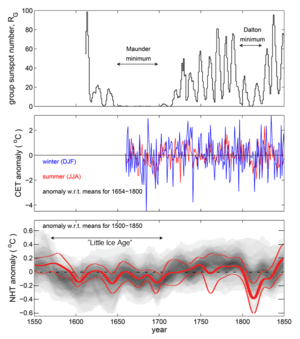

The Maunder Minimum roughly coincided with the middle part of the Little Ice Age, during which Europe and North America experienced colder than average temperatures. Whether there is a causal relationship, however, is still controversial.[13] Research at the Technical University of Denmark and the Hebrew University of Jerusalem has linked large solar eruptions to changes in the Earth's cloud cover and clouds are known to affect global temperatures.[14] The current best hypothesis for the cause of the Little Ice Age is that it was the result of volcanic action.[15][16] The onset of the Little Ice Age also occurred well before the beginning of the Maunder minimum[15], and northern-hemisphere temperatures during the Maunder minimum were not significantly different from the previous 80 years ,[17] suggesting a decline in solar activity was not the main causal driver of the Little Ice Age.

The correlation between low sunspot activity and cold winters in England has recently been analyzed using the longest existing surface temperature record, the Central England Temperature record.[18] They emphasize that this is a regional and seasonal effect relating to European winters, and not a global effect. A potential explanation of this has been offered by observations by NASA's Solar Radiation and Climate Experiment, which suggest that solar UV output is more variable over the course of the solar cycle than scientists had previously thought.[19] In 2011, an article was published in the Nature Geoscience journal that uses a climate model with stratospheric layers and the SORCE data to tie low solar activity to jet stream behavior and mild winters in some places (southern Europe and Canada/Greenland) and colder winters in others (northern Europe and the United States).[20] In Europe, examples of very cold winters are 1683–84, 1694–95, and the winter of 1708–09.[21]

The term "Little Ice Age" applied to the Maunder minimum is something of a misnomer, as it implies a period of unremitting cold (and on a global scale), which was not the case. For example, the coldest winter in the Central England Temperature record is 1683–1684, but the winter just two years later (both in the middle of the Maunder minimum) was the fifth-warmest in the whole 350-year CET record. Also, summers during the Maunder minimum were not significantly different from those seen in subsequent years. The drop in global average temperatures in paleoclimate reconstructions at the start of the Little Ice Age was between about 1560 and 1600, whereas the Maunder minimum began almost 50 years later.

Other observations

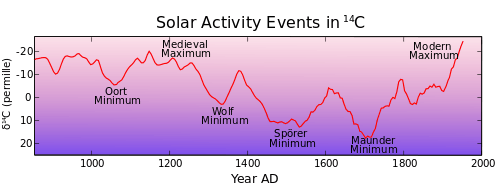

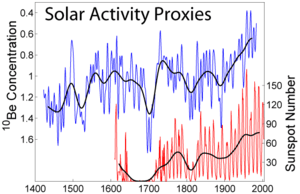

Past solar activity may be recorded by various proxies, including carbon-14 and beryllium-10.[22] These indicate lower solar activity during the Maunder Minimum. The scale of changes resulting in the production of carbon-14 in one cycle is small (about one percent of medium abundance) and can be taken into account when radiocarbon dating is used to determine the age of archaeological artifacts. The interpretation of the beryllium-10 and carbon-14 cosmogenic isotope abundance records stored in terrestrial reservoirs such as ice sheets and tree rings has been greatly aided by reconstructions of solar and heliospheric magnetic fields based on historic data on Geomagnetic storm activity, which bridge the time gap between the end of the usable cosmogenic isotope data and the start of modern spacecraft data.[23][24]

Other historical sunspot minima have been detected either directly or by the analysis of the cosmogenic isotopes; these include the Spörer Minimum (1450–1540), and less markedly the Dalton Minimum (1790–1820). In a 2012 study, sunspot minima have been detected by analysis of carbon-14 in lake sediments.[25] In total, there seem to have been 18 periods of sunspot minima in the last 8,000 years, and studies indicate that the Sun currently spends up to a quarter of its time in these minima.

A paper based on an analysis of a Flamsteed drawing, suggests that the Sun's surface rotation slowed in the deep Maunder minimum (1684).[26]

During the Maunder Minimum aurorae had been observed seemingly normally, with a regular decadal-scale cycle.[27][28] This is somewhat surprising because the later, and less deep, Dalton sunspot minimum is clearly seen in auroral occurrence frequency, at least at lower geomagnetic latitudes.[29] Because geomagnetic latitude is an important factor in auroral occurrence, (lower-latitude aurorae requiring higher levels of solar-terrestrial activity) it becomes important to allow for population migration and other factors that may have influenced the number of reliable auroral observers at a given magnetic latitude for the earlier dates.[30] Decadal-scale cycles during the Maunder minimum can also be seen in the abundances of the beryllium-10 cosmogenic isotope (which unlike carbon-14 can be studied with annual resolution) [31] but these appear to be in antiphase with any remnant sunspot activity. An explanation in terms of solar cycles in loss of solar magnetic flux was proposed in 2012.[32]

The fundamental papers on the Maunder minimum (Eddy, Legrand, Gleissberg, Schröder, Landsberg et al.) have been published in Case studies on the Spörer, Maunder and Dalton Minima.[33]

See also

References

- ↑ Bruce Weber, John A. Eddy, Solar Detective, Dies at 78, New York Times, June 17, 2009 (retrieved 28 July 2015)

- ↑ Eddy J.A. (June 1976). "The Maunder Minimum". Science. 192 (4245): 1189–1202. Bibcode:1976Sci...192.1189E. doi:10.1126/science.192.4245.1189. PMID 17771739. PDF Copy Archived 2010-02-16 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Who named the Maunder Minimum?

- ↑ E.W.M. (1890) "Professor Spoerer's researches on sun-spots," Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 50 : 251–252.

- ↑ E. Walter Maunder (August 1, 1894) "A prolonged sunspot minimum," Knowledge, 17 : 173–176.

- ↑ See:

- Spörer (1887) "Über die Periodicität der Sonnenflecken seit dem Jahre 1618, vornehmlich in Bezug auf die heliographische Breite derselben, und Hinweis auf eine erhebliche Störung dieser Periodicität während eines langen Zeitraumes" (On the periodicity of sunspots since the year 1618, especially with respect to the heliographic latitude of the same, and reference to a significant disturbance of this periodicity during a long period), Vierteljahrsschrift der Astronomischen Gesellschaft (Leipzig), 22 : 323–329.

- G. Spoerer (February 1889) "Sur les différences que présentent l'hémisphère nord et l'hémisphère sud du Soleil" (On the differences that the northern hemisphere and southern hemisphere of the sun present), Bulletin Astronomique, 6 : 60–63.

- ↑ Brück, Mary T. (1994). "Alice Everett and Annie Russell Maunder, torch bearing women astronomers". Irish Astronomical Journal. 21: 280–291. Bibcode:1994IrAJ...21..281B.

- ↑ John E. Beckman & Terence J. Mahoney. "The Maunder Minimum and Climate Change: Have Historical Records Aided Current Research?". Astronomical Society of the Pacific.

- ↑ Usoskin; et al. (2015). "The Maunder minimum (1645–1715) was indeed a grand minimum: A reassessment of multiple datasets". Astron. Astrophys. 581: A95. arXiv:1507.05191. Bibcode:2015A&A...581A..95U. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201526652.

- ↑ Lockwood, M.; et al. (July 2014). "Centennial variations in sunspot number, open solar flux and streamer belt width: 2. Comparison with the geomagnetic data". J. Geophys. Res. 119 (7): 5183–5192. Bibcode:2014JGRA..119.5183L. doi:10.1002/2014JA019972. PDF Copy

- ↑ "Hadley Centre Central England Temperature (HadCET) dataset".

- ↑ "Climate Change 2013, The Physical Science Basis, WG1, 5th Assessment Report, IPCC".

- ↑ Plait, Phil, Are we headed for a new ice age?, Discover, June 17, 2011 (retrieved 16 July 2015)

- ↑ https://phys.org/news/2016-08-solar-impact-earth-cloud.html

- 1 2 Miller et al. 2012. "Abrupt onset of the Little Ice Age triggered by volcanism and sustained by sea-ice/ocean feedbacks" Geophysical Research Letters 39, 31 January; see press release on AGU website (retrieved 16 July 2015).

- ↑ Was the Little Ice Age Triggered by Massive Volcanic Eruptions? ScienceDaily, 30 January 2012 (accessed 21 May 2012)

- ↑ Owens et al., (2017). "The Maunder Minimum and the Little Ice Age: An update from recent reconstructions and climate simulations". Space Weather and Space Climate. 7 (A33). doi:10.1051/swsc/2017034.

- ↑ Lockwood, M.; et al. (February 2010). "Are cold winters in Europe associated with low solar activity?". Env. Res. Lett. 5 (2): 024001. Bibcode:2010ERL.....5b4001L. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/5/2/024001. PDF Copy

- ↑ Harder, J.A.; et al. (April 2009). "Trends in solar spectral irradiance variability in the visible and infrared". Geophys. Res. Lett. 36 (7): L07801. Bibcode:2009GeoRL..36.7801H. doi:10.1029/2008GL036797.

- ↑ Ineson, S.; et al. (October 2011). "Solar forcing of winter climate variability in the Northern Hemisphere". Nature Geoscience. 4 (11): 753–757. Bibcode:2011NatGe...4..753I. doi:10.1038/ngeo1282.

- ↑ Niles' Weekly Register, Volume 15, Supplement, History of the Weather

- ↑ Usoskin I.G. (2017). "A History of Solar Activity over Millennia". Living Reviews in Solar Physics. 14 (3). Bibcode:2017LRSP...14....3U. doi:10.1007/s41116-017-0006-9.

- ↑ Lockwood M.; et al. (June 1999). "A doubling of the sun's coronal magnetic field during the last 100 years". Nature. 399 (6735): 437–439. Bibcode:1999Natur.399..437L. doi:10.1038/20867. PDF Copy Archived 2011-04-30 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Lockwood M. (2013). "Reconstruction and Prediction of Variations in the Open Solar Magnetic Flux and Interplanetary Conditions". Living Reviews in Solar Physics. 10 (4). Bibcode:2013LRSP...10....4L. doi:10.12942/lrsp-2013-4. PDF Copy

- ↑ Celia Martin-Puertas; Katja Matthes; Achim Brauer; Raimund Muscheler; Felicitas Hansen; Christof Petrick; Ala Aldahan; Göran Possnert; Bas van Geel (April 2, 2012). "Regional atmospheric circulation shifts induced by a grand solar minimum". Nature Geoscience. 5 (6): 397–401. Bibcode:2012NatGe...5..397M. doi:10.1038/ngeo1460.

- ↑ Vaquero JM, Sánchez-Bajo F, Gallego MC (2002). "A Measure of the Solar Rotation During the Maunder Minimum". Solar Physics. 207 (2): 219–222. Bibcode:2002SoPh..207..219V. doi:10.1023/A:1016262813525.

- ↑ Schröder, Wilfried (1992). "On the existence of the 11-year cycle in solar and auroral activity before and during the Maunder Minimum". Journal of Geomagnetism and Geoelectricity. 44 (2): 119–28. Bibcode:1992JGG....44..119S. doi:10.5636/jgg.44.119. ISSN 0022-1392.

- ↑ Legrand, JP; Le Goff, M; Mazaudier, C; Schröder, W (1992). "Solar and auroral activities during the seventeenth century". Acta Geodaetica et Geophysica Hungarica. 27 (2–4): 251–282.

- ↑ Nevanlinna, H. (1995). "Auroral observations in Finland – Visual sightings during the 18th and 19th centuries". Journal of Geomagnetism and Geoelectricity. 47 (10): 953–960. Bibcode:1995JGG....47..953N. doi:10.5636/jgg.47.953. ISSN 0022-1392. PDF Copy

- ↑ Vázquez, M.; et al. (2014). "Long-term Spatial and Temporal Variations of Aurora Borealis Events in the Period 1700 – 1905". Solar Physics. 289 (5): 1843–1861. arXiv:1309.1502. Bibcode:2014SoPh..289.1843V. doi:10.1007/s11207-013-0413-6. ISSN 0038-0938. PDF Copy

- ↑ Beer, J.; et al. (1988). "An Active Sun Throughout the Maunder Minimum". Solar Physics. 181 (1): 237–249. Bibcode:1998SoPh..181..237B. doi:10.1023/A:1005026001784. PDF Copy Archived 2014-08-21 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Owens, M.J..; et al. (2012). "Heliospheric modulation of galactic cosmic rays during grand solar minima: Past and future variations". Geophys. Res. Lett. 39 (19): L19102. Bibcode:2012GeoRL..3919102O. doi:10.1029/2012GL053151. PDF Copy Archived 2014-08-22 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Schröder, Wilfried (2005). Case studies on the Spörer, Maunder, and Dalton minima. Beiträge zur Geschichte der Geophysik und Kosmischen Physik. 6. Potsdam: AKGGP, Science Edition.

Further reading

- Luterbach, J.; et al. (2001). "The Late Maunder Minimum (1675–1715) – A Key Period for Studying Decadal Scale Climatic Change in Europe". Climatic Change. 49 (4): 441–462. doi:10.1023/A:1010667524422.

- Soon, Willie Wei-Hock; Yaskell, Steven H. (2003). The Maunder Minimum and the Variable Sun-Earth Connection. River Edge, New Jersey: World Scientific. ISBN 981-238-275-5.

- What's wrong with the sun? (Nothing)

- Solar poles to become quadrupolar in May 2012 (Hinode)

- Barnard, L.; et al. (2011). "Predicting Space Climate Change". Geophys. Res. Lett. 38 (16): L16103. Bibcode:2011GeoRL..3816103B. doi:10.1029/2011GL048489.

External links

- HistoricalClimatology.com, further links and resources, updated 2014

- Climate History Network, network of historical climatologists, updated 2014