Mary R. Platt Hatch

| Mary R. Platt Hatch | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

Mary Roxanna Platt June 19, 1848 Stratford, New Hampshire, U.S. |

| Died |

November 28, 1935 (aged 87) Santa Monica, California, U.S. |

| Pen name | Mabel Percy |

| Occupation | author |

| Language | English |

| Spouse | Antipas Morton Hatch |

Mary R. Platt Hatch (pen name Mabel Percy; June 19, 1848 – November 28, 1935) was an American author from New Hampshire. She contributed stories to the Transcript, Mountaineer, Fireside Companion, Chicago Ledger, Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, Springfield Republican, Granite Monthly, The Writer, and several magazines including the Portland Transcript, The Saturday Evening Post, Peterson's Magazine, as well as other periodicals. Her novels included The Strange Disappearance of Eugene Comstocks, The Bank Tragedy: A Novel, and The Missing Man, among others.

Early life and education

Mary Roxanna Platt was born June 19, 1848, in Stratford, New Hampshire.[1][2] She was the daughter of Charles G. and Mary (Blake) Platt. Her life as a farmer's daughter, and later as a farmer's wife, was spent on farms in the Connecticut River valley. As a child, she was quiet and sensitive, with scholarly tastes, writing little stories and poems before she was 12 years old. She attended the common district school until about 15 years of age, and at that time entered into advanced classes at the Lancaster academy, where she took high rank in mathematics, French, and rhetoric. Her ability as a writer was first recognized here. The weekly compositions, her contributions to the lyceum papers, and an occasional article in the county papers were favorably commented upon, and her pen name of "Mabel Percy" was soon known to the readers of the Portland Transcript, Saturday Evening Post, Peterson's Magazine, and other periodicals.[3]

Career

.png)

After completing her education, she married Antipas Morton Hatch,[2] and became the mother of two sons. Being a farmer's wife, and living on a large farm, her writings were her recreation, and she was accustomed to writing during intervals of domestic life.[4]

Hatch's versatility afforded her to work in various areas of literature; for instance, at the same time that she was engaged in writing "The Bank Tragedy," a biographical sketch for The Writer, she also wrote a series of dialect papers. She contributed several excellent poems, which were widely copied, among them an "Ode to J. G. Blaine". She contributed stories for the Transcript, Mountaineer, Fireside Companion, Chicago Ledger, Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, Springfield Republican, Granite Monthly, The Writer, and several magazines. Among her most noteworthy stories are her "Upland Mystery" and "The Bank Tragedy", both of which appeared in the Transcript, with favorable comments from the US press. "Upland Mystery" was afterwards put in book form, and received a large sale. Poems, with a biographical note, were included in New Hampshire Poets, published in 1883.[3] Hatch served as Literary Contributor to Willard and Livermore's American Women: Fifteen Hundred Biographies with Over 1,400 Portraits: A Comprehensive Encyclopedia of the Lives and Achievements of American Women During the Nineteenth Century (1897).[4]

She died in Santa Monica, California, November 28, 1935.[1]

Books

Though sensational in form, Hatch's books claimed to have a purpose. "The Upland Mystery" taught that when a person becomes a murderer he arrays the whole world against him. The detective says, "I have seen apparent impossibilities group themselves about a crime, and point toward it instead of from it. It is a rendering of the old saying that 'murder will out.' Nature's forces cast out evidence, the movement of a muscle betrays it, a foot is caught tripping that never tripped before, and leaves a proof behind. I tell you, if I had the disposition to commit crime of this nature I should not dare, from what I know of the impossibility of eluding penalty, which is a life for a life."[3]

In "Quicksands" the keynote is ambition and other "sins which do so easily beset". In "The Bank Tragedy" it is inherited sin. Warren, in his confession, is made to say, "I am what I am through the force of inherited traits. If I might preach in yonder pulpit I would say, 'See to it that your deeds and thoughts are what they should be, for they will strike root somewhere. If not in yourself, then in the person of your children or your children's children.' . . . I once heard an idiotic preacher say that the soul of every child was like a fair white sheet of paper, on which you could trace what characters you liked. I wanted to shout out a denial. I wanted to say that the paper was already written over, laced and interlaced, as ladies write their letters, by the thoughts and deeds of a million ancestors. The childhood and training of my brother and I were precisely the same; but Joseph was honest and straight-forward, while I looked at everything from an oblique standpoint." On the other hand, Jessie says, "True, he inherited the traits that worked his ruin; but who is perfect? It was his part to root out his besetting sins and fly from temptation instead of playing with them as though they were toys instead of thunderbolts which might at anytime strike him."[3]

Selected works

- Merry Christmas : all pictures (1881; juvenile audience)

- The Upland mystery : a tragedy of New England (1887)

- The bank tragedy A novel (1891)

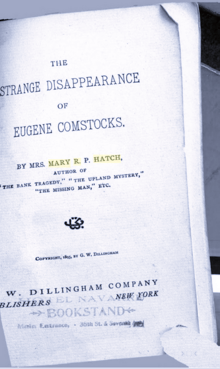

- The strange disappearance of Eugene Comstocks (1895)

- The great Hampton bank robbery (1901)

- Dartmouth and the Webster centennial (1901)

- The gossiping guide to Dartmouth and to Hanover (1905)

- St. Johnsbury, Vermont, and its industries (1906)

- Lancaster, New Hampshire (1906)

- The dreamer : a romantic drama in three acts (1913)

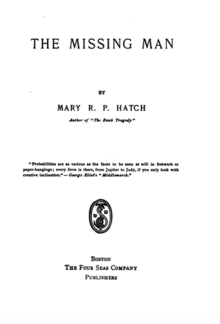

- The missing man (1922)

- Mademoiselle Vivine. A vaudeville sketch (1927)

- Mrs. Bright's visitor. A comedy in one act. (1928)

- The Berkeley Street mystery (1928)

References

- 1 2 Benbow-Pfalzgraf 2000, p. 190.

- 1 2 Daughters of the American Revolution 1925, p. 59.

- 1 2 3 4 Metcalf, McClintock & Hammond 1889, p. 173-75.

- 1 2 Willard & Livermore 1897, p. 188.

Attribution

Bibliography

- Benbow-Pfalzgraf, Taryn (2000). American women writers: a critical reference guide : from colonial times to the present. 2. St. James Press. ISBN 978-1-55862-431-3.

- Daughters of the American Revolution (1925). Lineage Book - National Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution. 78-79. Daughters of the American Revolution.