Maria Margaretha Kirch

| Maria Margaretha Kirch | |

|---|---|

| Born |

Maria Margaretha Winkelmann 25 February 1670 Panitzsch near Leipzig, Electorate of Saxony |

| Died |

29 December 1720 (aged 50) Berlin, Kingdom of Prussia |

| Residence | Prussia |

| Nationality | German |

| Awards | Gold medal of Royal Academy of Sciences, Berlin (1709) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Mathematics and Astronomy |

Maria Margaretha Kirch (née Winckelmann, in historic sources named Maria Margaretha Kirchin; 25 February 1670 – 29 December 1720) was a German astronomer, and one of the first famous astronomers of her period due to her writings on the conjunction of the sun with Saturn, Venus, and Jupiter in 1709 and 1712 respectively.[1]

Early life

Maria was educated from an early age by her father, a Lutheran minister, who believed that she deserved an education equivalent to that given to young boys of the time.[2] At the age of 13 she had lost her both her father and mother. By that time she had also received a general education by her brother-in-law Justinus Toellner and the well-known astronomer Christoph Arnold, who lived nearby.[3] Her education was continued by her uncle. As Maria, had an interest in astronomy from an early age, she took the opportunity of studying with Arnold, a self-taught astronomer who worked as a farmer in Sommerfeld, near Leipzig. She became Arnold's unofficial apprentice and later his assistant, living with him and his family.[2] However, astronomy was not organised entirely along guild lines.[4]

Through Arnold, Maria met the famous German astronomer and mathematician Gottfried Kirch, who was 30 years her senior. They married in 1692, later having four children, all of whom followed in their parents' footsteps by studying astronomy.[5] In 1700 the couple moved to Berlin, as the elector ruler of Brandenburg Frederick III, later Frederick I of Prussia, had appointed Gottfried Kirch as his royal astronomer.[6]

Career, observations and publications

Gottfried Kirch gave his wife further instruction in astronomy, as he did for his sister and many other students. Women were not allowed to attend universities in Germany, but the actual work of astronomy, and the observation of the heavens, took place largely outside the universities.[4] Thus Kirch became one of the few women active in astronomy in the 1700s.[8] She became widely known as the Kirchin, the feminine version of the family name.[9] It was not unheard of in the Holy Roman Empire that a woman should be active in astronomy. Maria Cunitz, Elisabeth Hevelius and Maria Clara Eimmart had been active astronomers in the 17th century.[10]

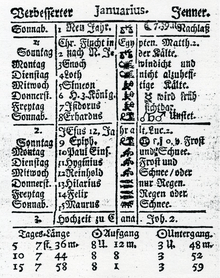

Through an edict Friedrich III introduced a monopoly for calendars in Brandenburg, and later Prussia, imposing a calendar tax. The income from this monopoly was to pay astronomers and members of the Berlin Academy of Sciences which Friedrich III founded in July 1700. Friedrich III also went on to build an observatory, which was inaugurated in January 1711. Assisted by his wife Gottfried Kirch prepared the first calendar of a series, entitled Chur-Brandenburgischer Verbesserter Calender Auff das Jahr Christi 1701, which became very popular.[3]

Maria and Gottfried worked together as a team. In typical guild fashion she moved on from her position as Arnold's apprentice, to become assistant to her husband. Her husband had studied astronomy at the University of Jena and had served as apprentice to Johannes Hevelius.[4] At the academy she worked as his unofficial but recognised assistant. Women’s position in the sciences was akin to their position in the guilds, valued but subordinate.[11] Together they made observations and performed calculations to produce calendars and ephemerides. From 1697, the Kirchs also began recording weather information. The data collected by the Kirchs was used to produce calendars and almanacs and was also very useful in navigation. The academy in Berlin handled sales of their calendars.[2]

During the first decade of her work at the academy as her husband’s unofficial assistant Kirch would observe the heavens, every evening starting at 9pm. During such a routine observation she discovered a comet.[12] On 21 April 1702 Kirch discovered the so-called "Comet of 1702" (C/1702 H1). Today there is no doubt about Kirch's priority in discovering C/1702 H1.[12] In his notes from that night her husband recorded:

"Early in the morning (about 2:00 AM) the sky was clear and starry. Some nights before, I had overserved a variable star and my wife (as I slept) wanted to find and see it for herself. In so doing, she found a comet in the sky. At which time she woke me, and I found that it was indeed a comet... I was surprised that I had not seen it the night before".[13]

Germany's only scientific journal at the time Acta eruditorum was in Latin. Kirch's subsequent publications in her own name were all in German. At the time her husband did not hold an independent chair at the academy and the Kirchs worked as a team on common problems. The couple observed the heavens together, he observed the north and she the south, thus they made observations that a single person could not have done accurately.[13]

Kirch continued to pursue her astronomy work, publishing in German under her own name, and with the proper recognition. Her publications, which included her observations on the Aurora Borealis (1707), the pamphlet Von der Conjunction der Sonne des Saturni und der Venus on the conjunction of the sun with Saturn and Venus (1709), and the approaching conjunction of Jupiter and Saturn in 1712 became her lasting contributions to astronomy.[5] Before her the only female astronomer in the Holy Roman Empire that had published under her own name had been Maria Cunitz.[11] The family friend and vice-president of the academy, Alphonse des Vignoles said in Kirch's eulogy: "If one considers the reputations of Frau Kirch and Frau Cunitz, one must admit that there is no branch of science… in which women are not capable of achievement, and that in astronomy, in particular, Germany takes the prize above all other states in Europe."[14]

In 1709 academy president Gottfried von Leibniz presented her to the Prussian court, where Kirch explained her sightings of sunspots.[13] He said about her:

"There is a most learned woman who could pass as a rarity. Her achievement is not in literature or rhetoric but in the most profound doctrines of astronomy... I do not believe that this woman easily finds her equal in the science in which she excels... She favours the Copernican system (the idea that the sun is at rest) like all the learned astronomers of our time. And it is a pleasure to hear her defend that system through the Holy Scripture in which she is also very learned. She observes with the best observers and knowns how to handle marvellously the quadrant and the telescope".[15]

After her husband died in 1710, Kirch attempted to assume his place as astronomer and calendar maker at the Royal Academy of Sciences. Despite her petition being supported by Leibniz, the president of the academy, the executive council of the academy rejected her demand for a formal position as that "what we concede to her could serve as an example in the future".[6] In her petition Kirch set out her qualifications for the position. She argued that she was well qualified because she had been instructed by her husband in astronomical calculation and observation. She emphasised that she had engaged in astronomical work since her marriage and had worked at the academy since her husband's appointment 10 years earlier. In her petition Kirch said that "for some time, while my dear departed husband was weak and ill, I prepared the calendar from his calculations and published it under his name". For Kirch an appointment at the academy would have not been just a mark of honour, but was vital in securing an income for herself and her children. In her petition she said that her husband had not left her with means of support. The guild tradition of the time did establish a legitimate claim for Kirch to take over her husband's position after his death. But these traditions were not followed by the new institutions of science.[16]

While Kirch had carried out important work at the academy, she did not have a university degree, which at that time nearly every member of the academy had. But the academy secretary Johann Theodor Jablonski also cautioned Leibniz, "that she be kept on in an official capacity to work on the calendar or to continue with observations simply will not do. Already during her husband's lifetime the academy was burdened with ridicule because its calendar was prepared by a woman. If she were now to be kept on in such a capacity, mouths would gape even wider". Leibniz was the only member of the academy council who supported her appointment. In one of the last council meetings he presided over before leaving Berlin in 1711 Leibniz tried to secure financial assistance for Kirch.[17]

Kirch was of the opinion that her petitions were denied due to her gender. This is somewhat supported by the fact that Johann Heinrich Hoffmann, who had little experience, was appointed to her husband's place instead of her. Hoffmann soon fell behind with his work and failed to make required observations. It was even suggested that Kirch become his assistant.[2] Kirch wrote "Now I go through a severe desert, and because... water is scarce... the taste is bitter". However, she was admitted by the Berlin Academy of Sciences.[2]

In 1711, she published Die Vorbereitung zug grossen Opposition, a well-received pamphlet in which she predicted a new comet, followed by a pamphlet concerning Jupiter and Saturn. In 1712 Kirch accepted the patronage Bernhard Friedrich von Krosigk, who was an enthusiastic amateur astronomer, and began work in his observatory. She and her husband had worked at Krosigk's observatory while the academy observatory was being built. At Krosigk's observatory she reached the rank of master astronomer.[18]

After Baron von Krosigk died in 1714 Kirch moved to Danzig to assist a professor of mathematics for a short time before returning. In 1716 Kirch and her son, who had just finished university, received an offer to work as astronomers for the Russian czar Peter the Great,[18] but preferred to remain in Berlin where she continued to calculate calendars for locales such as Nuremberg, Dresden, Breslau, and Hungary.

She had trained her son Christfried Kirch and daughters Christine Kirch and Margaretha Kirch to act as her assistants in the family's astronomical work, continuing the production of calendars and almanacs as well as making observations. In 1716 her son Christfried and Johann Wilhelm Wagner were appointed observers at the academy observatory following Hoffmann's death.[18] Kiel moved back to Berlin to act as her son's assistant[6] together with her daughter Christine.[19] She was once again working at the academy observatory calculating calendars.[18] Academy members complained that she took too prominent a role and was "too visible at the observatory when strangers visit." Kirch was ordered to "retire to the background and leave the talking to... her son". Kirch refused to comply and was forced by the academy to give up her house on the observatory grounds.[20]

Kirch continued working in private.[21] Kirch died of a fever in Berlin on the 29 December 1720.[20]

See also

References

- ↑ Alic, Margaret (1986). Hypatia's heritage. British Library: The Women's Press Limited. p. 121. ISBN 0-7043-3954-4.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Schiebinger, Londa (1989). The Mind Has No Sex?: Women in the Origins of Modern Science. Harvard University Press. pp. 21–38. ISBN 067457625X.

- 1 2 Virginia Trimble, Thomas R. Williams, Katherine Bracher, Richard Jarrell, Jordan D. Marché & F. Jamil Ragep (2007). Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 639. ISBN 9780387304007.

- 1 2 3 Arina Angerman, Geerte Binnema, Annemieke Keunen, Vefie Poels & Jacqueline Zirkzee (2012). Current Issues in Women's History: International Conference on Women's History. Routledge. p. 24. ISBN 9781136248801.

- 1 2 Alic, Margaret (1986). Hypatia's Heritage: A History of Women in Science from Antiquity to the late Nineteenth Century. Beacon Press. ISBN 0-8070-6731-8.

- 1 2 3 Lisa Yount (2007). A to Z of Women in Science and Math. Infobase Publishing. p. 157. ISBN 9781438107950.

- ↑ Roland Wielen (March 2016). "Leibniz-Objekt des Monats: Leibniz und das Kalender-Edikt von 1700". Berlin-Brandenburgische Akademie der Wissenschaften.

- ↑ Virginia Trimble, Thomas R. Williams, Katherine Bracher, Richard Jarrell, Jordan D. Marché & F. Jamil Ragep (2007). Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 639. ISBN 9780387304007.

- ↑ Virginia Trimble, Thomas R. Williams, Katherine Bracher, Richard Jarrell, Jordan D. Marché & F. Jamil Ragep (2007). Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 638. ISBN 9780387304007.

- ↑ Arina Angerman, Geerte Binnema, Annemieke Keunen, Vefie Poels & Jacqueline Zirkzee (2012). Current Issues in Women's History: International Conference on Women's History. Routledge. p. 34. ISBN 9781136248801.

- 1 2 Arina Angerman, Geerte Binnema, Annemieke Keunen, Vefie Poels & Jacqueline Zirkzee (2012). Current Issues in Women's History: International Conference on Women's History. Routledge. p. 25. ISBN 9781136248801.

- 1 2 Dorothy O. Helly & Susan Reverby (1992). Gendered Domains: Rethinking Public and Private in Women's History : Essays from the Seventh Berkshire Conference on the History of Women. Cornell University Press. p. 60. ISBN 9780801497025.

- 1 2 3 Dorothy O. Helly & Susan Reverby (1992). Gendered Domains: Rethinking Public and Private in Women's History : Essays from the Seventh Berkshire Conference on the History of Women. Cornell University Press. p. 61. ISBN 9780801497025.

- ↑ Dorothy O. Helly & Susan Reverby (1992). Gendered Domains: Rethinking Public and Private in Women's History : Essays from the Seventh Berkshire Conference on the History of Women. Cornell University Press. p. 57. ISBN 9780801497025.

- ↑ Dorothy O. Helly & Susan Reverby (1992). Gendered Domains: Rethinking Public and Private in Women's History : Essays from the Seventh Berkshire Conference on the History of Women. Cornell University Press. p. 63. ISBN 9780801497025.

- ↑ Dorothy O. Helly & Susan Reverby (1992). Gendered Domains: Rethinking Public and Private in Women's History : Essays from the Seventh Berkshire Conference on the History of Women. Cornell University Press. p. 66. ISBN 9780801497025.

- ↑ Dorothy O. Helly & Susan Reverby (1992). Gendered Domains: Rethinking Public and Private in Women's History : Essays from the Seventh Berkshire Conference on the History of Women. Cornell University Press. p. 65. ISBN 9780801497025.

- 1 2 3 4 Dorothy O. Helly & Susan Reverby (1992). Gendered Domains: Rethinking Public and Private in Women's History : Essays from the Seventh Berkshire Conference on the History of Women. Cornell University Press. p. 67. ISBN 9780801497025.

- ↑ Virginia Trimble, Thomas R. Williams, Katherine Bracher, Richard Jarrell, Jordan D. Marché & F. Jamil Ragep (2007). Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 637. ISBN 9780387304007.

- 1 2 Lisa Yount (2007). A to Z of Women in Science and Math. Infobase Publishing. p. 158. ISBN 9781438107950.

- ↑ Dorothy O. Helly & Susan Reverby (1992). Gendered Domains: Rethinking Public and Private in Women's History : Essays from the Seventh Berkshire Conference on the History of Women. Cornell University Press. p. 68. ISBN 9780801497025.