Peggy Eaton

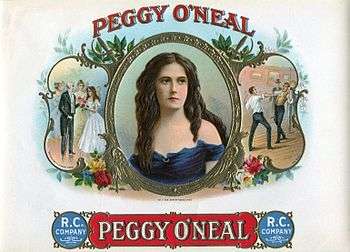

Margaret O'Neill (or O'Neale) Eaton (December 3, 1799 – November 8, 1879), better known as Peggy Eaton, was the daughter of Rhoda Howell and William O'Neale,[1] the owner of Franklin House, a popular Washington, D.C. hotel. Peggy was noted for her beauty, wit and vivacity. Her marriage to United States Senator John Henry Eaton caused some controversy, as she had been recently widowed only a few months earlier, when her husband died while at sea.

After Eaton was appointed as Secretary of War, rumors continued and Peggy Eaton was snubbed by other cabinet wives. Her honor was defended by President Andrew Jackson and she became the subject of the Petticoat affair. Relations among the president's Cabinet became so strained that he replaced most of the members.[2]

First marriage

About 1816, at age 17, Margaret O'Neale married John B. Timberlake, a 39-year-old purser in the Navy. Her parents gave them a house across from the hotel, and they met many politicians who stayed there. In 1818 they met and befriended John Henry Eaton, a 28-year-old widower and newly elected senator from Tennessee. Margaret and John Timberlake had two children. A third had died in infancy.[3]

John Timberlake died in 1828 while at sea in the Mediterranean, in service on a four-year voyage. When the widow Margaret Timberlake married Senator Eaton shortly after the turn of the year, rumors circulated that Timberlake had committed suicide because of despair at an alleged affair between the two.

Second marriage and scandal

Senator Eaton was a close friend of President Andrew Jackson, who in 1829 appointed him Secretary of War. The sudden elevation of Mrs. Eaton into the Cabinet social circle was resented by the wives of several of Jackson's appointees. They criticized Mrs. Eaton for allegedly having had an affair with Eaton prior to her marriage.

The wives of the Cabinet members snubbed Mrs. Eaton socially, which angered President Jackson. He tried unsuccessfully to coerce them into acceptance, backing her as a matter of honor. Eventually, and partly because of the hostility aroused by rumors about Mrs. Eaton, he almost completely reorganized his Cabinet. The event is referred to as the Petticoat affair.

The effect of the incident on the political fortunes of the vice president, John C. Calhoun, whose wife, Floride Calhoun, was one of those who snubbed Mrs. Eaton, was perhaps most important. Partly on this account, Jackson transferred his favor to widower Martin Van Buren, the Secretary of State, who had taken the Eatons' side in the quarrel and had shown positive social attention to Mrs. Eaton. Some attributed his subsequent elevation to the vice-presidency and presidency through Jackson's favor as related to this incident.

Margaret O’Neill Eaton answers her critics (from historian Jon Meacham’s American Lion (2008) -

“I suppose I must have been very vivacious” she said in her old age. “I was a lively girl and had many things about me to increase my vanity and help to spoil me. While I was still in pantalettes and rolling hoops with other girls, I had the attention of men, young and old, enough to turn a girl’s head.” [4] “It must be remembered that I had been raised in the gayest society and was naturally of a mercurial temperament.” [5]

Meacham points out that “at various points in her life she was courted by an adjutant general, a major and a captain – which delighted her.”

“The fact is,” wrote Margaret, “I never had a lover who was not a gentleman and was not in a good position in society.” She was, according to Meacham “by her own account…an outgoing flirt” - her tongue was “ungoverned, and ungovernable.” [4]

“I must have said a great many foolish things” wrote Margaret, “I am sure I did very few wise ones. I was foolish, hasty, but not vicious.” [5]

She expressed her opinion of her critics this way: “I was quite as independent as they, and had more powerful friends…None of them had beauty, accomplishments or graces in society of any kind, and for these reasons…they were jealous of me.” [6]

Meacham observes that, “it’s impossible ... to assess the truth of the charges”[5] lodged by her enemies, but “she offers this “interesting defense”:

“Just let a little commonsense be exercised. While I do not pretend to be a saint, and do not think I was ever very much stocked with sense, and lay no claim to be a model woman in any way, I put it to the candor of the world whether the slanders which have been uttered against me are to be believed.” [5]

Third marriage and later life

Three years after the death of her second husband, Margaret Eaton married Antonio Gabriele Buchignani, an Italian music teacher and dancing master, on June 7, 1859.[7] She was 59 and he was in his mid 20s. The marriage reignited much of the social stigma Margaret had carried earlier in life.

In 1866, their seventh year of marriage, Buchignani ran off to Europe with the bulk of his wife's fortune as well as her 17-year-old granddaughter Emily E. Randolph. He married Randolph after he and his wife divorced in 1869.[8][9][10][11]

Eaton obtained a divorce from Buchignani but she was not able to recover her financial standing. She died in poverty in Washington, D.C. on November 8, 1879. She was buried at Oak Hill Cemetery.[12]

Cultural references

The 1936 film The Gorgeous Hussy, starring Joan Crawford, was loosely based on the life of Margaret O'Neill.

References

- ↑ Coit, p. 546.

- ↑ Frederic D. Schwarz Archived 2009-10-05 at the Wayback Machine. "1831: 175 Years Ago: That Eaton Woman," American Heritage, April/May 2006.

- ↑ The Timberlakes' daughter Virginia, after a broken engagement to Philip Barton Key II, son of Francis Scott Key, married a French diplomat, Antoine Sampayo. One of the Sampayos' granddaughters was Olga de Meyer, the wife of photographer Adolph de Meyer.

- 1 2 Meacham, 2008, p. 67

- 1 2 3 4 Meacham, 2008, p. 68

- ↑ Meacham, 2008, p. 79

- ↑ Eli Field Cooley and William Scudder Cooley, Genealogy of Early Settlers of Trenton and Ewing, (W. S. Sharp, 1889), page 157

- ↑ {The Charleston daily News, September 14, 1868} In September 1868 Peggy appeared against Buchignani in the Jefferson Market Police Court

- ↑ Buchignani was close to the family of Abraham Lincoln, who appointed him as secretary to the U. S. legation at Naples and then assistant librarian of Congress. In New York City, during his marriage to Eaton, he operated the Opera Café and Hotel. According to an 1868 article about the case in The New York Times, Margaret Eaton agreed to divorce her husband if he would marry her granddaughter and restore her good name.

- ↑ Evening Star {Washington DC}, December 24, 1891 reports Gabriel Antonio Buchignani died in New York City on December 22, 1891 age 57 and that his Randolph wife "died some years ago"

- ↑ A son Emile Buchignani was born 1874 in Tennessee and married in New York City in 1908]

- ↑ Peggy Eaton at Find a Grave

Further reading

- "Margaret 'Peggy' Eaton", The Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture, Tennessee Historical Society, Nashville, Tennessee, 1998.

- Allgor, Catherine. Parlor Politics: In Which the Ladies of Washington Help Build a City and a Government. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2000.

- Coit, Margaret L. "Eaton, Margaret O'Neale", Notable American Women, Vol. 1, 4th ed., The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1975 (reprinted from 1911).

- Latner, Richard B. "The Eaton Affair Reconsidered." Tennessee Historical Quarterly (1977): 330-351 in JSTOR

- Marszalek, John F. The Petticoat Affair: Manners, Mutiny and Sex in Andrew Jackson's White House. Louisiana State University Press, 2000.

- Meacham, Jon. American Lion (2008)

- Wood, Kirsten E. "'One Woman so Dangerous to Public Morals': Gender and Power in the Eaton Affair." Journal of the Early Republic (1997): 237-275. in JSTOR

External links

- "Little Friend Peg", Founders of America

- Peggy Eaton at Find a Grave