Marcus Terentius Varro

Marcus Terentius Varro (/təˈrɛnʃiəs

Biography

_02.jpg)

Varro was born in or near Reate (now Rieti)[1] to a family thought to be of equestrian rank, and always remained close to his roots in the area, owning a large farm in the Reatine plain, reported as near Lago di Ripa Sottile,[2] until his old age. He supported Pompey, reaching the office of praetor, after having been tribune of the people, quaestor and curule aedile.[3] He was one of the commission of twenty that carried out the great agrarian scheme of Caesar for the resettlement of Capua and Campania (59 BC).[3]

During the civil war he commanded one of Pompey's armies in the Ilerda campaign.[4] He escaped the penalties of being on the losing side in the civil war through two pardons granted by Julius Caesar, before and after the Battle of Pharsalus.[5] Caesar later appointed him to oversee the public library of Rome in 47 BC, but following Caesar's death Mark Antony proscribed him, resulting in the loss of much of his property, including his library. As the Republic gave way to Empire, Varro gained the favour of Augustus, under whose protection he found the security and quiet to devote himself to study and writing.

Varro studied under the Roman philologist Lucius Aelius Stilo, and later at Athens under the Academic philosopher Antiochus of Ascalon. Varro proved to be a highly productive writer and turned out more than 74 Latin works on a variety of topics. Among his many works, two stand out for historians; Nine Books of Disciplines and his compilation of the Varronian chronology. His Nine Books of Disciplines became a model for later encyclopedists, especially Pliny the Elder. The most noteworthy portion of the Nine Books of Disciplines is its use of the liberal arts as organizing principles.[6] Varro decided to focus on identifying nine of these arts: grammar, rhetoric, logic, arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, musical theory, medicine, and architecture. Using Varro's list, subsequent writers defined the seven classical "liberal arts of the medieval schools".[6]

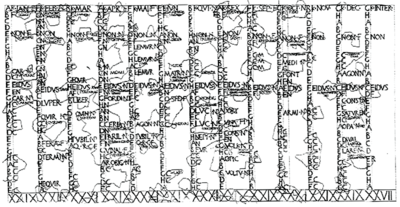

Calendars

The compilation of the Varronian chronology was an attempt to determine an exact year-by-year timeline of Roman history up to his time. It is based on the traditional sequence of the consuls of the Roman Republic — supplemented, where necessary, by inserting "dictatorial" and "anarchic" years. It has been demonstrated to be somewhat erroneous but has become the widely accepted standard chronology, in large part because it was inscribed on the arch of Augustus in Rome; though that arch no longer stands, a large portion of the chronology has survived under the name of Fasti Capitolini.

Works

Varro's literary output was prolific; Ritschl estimated it at 74 works in some 620 books, of which only one work survives complete, although we possess many fragments of the others, mostly in Gellius' Attic Nights. Called "the most learned of the Romans" by Quintilian,[7] Varro was recognized as an important source by many other ancient authors, among them Cicero, Pliny the Elder, Virgil in the Georgics, Columella, Aulus Gellius, Macrobius, Augustine, and Vitruvius, who credits him (VII.Intr.14) with a book on architecture.

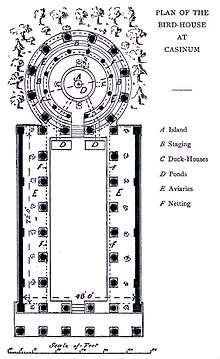

His only complete work extant, Rerum rusticarum libri tres (Three Books on Agriculture), has been described as "the well digested system of an experienced and successful farmer who has seen and practised all that he records."[8]

One noteworthy aspect of the work is his anticipation of microbiology and epidemiology. Varro warned his contemporaries to avoid swamps and marshland, since in such areas

there are bred certain minute creatures which cannot be seen by the eyes, but which float in the air and enter the body through the mouth and nose and cause serious diseases.[9][10][11]

Extant works

- De lingua latina libri XXV (or On the Latin Language in 25 Books, of which six books (V–X) survive, partly mutilated)

- Rerum rusticarum libri III (or Agricultural Topics in Three Books)

Known lost works

- Saturarum Menippearum libri CL or Menippean Satires in 150 books

- Antiquitates rerum humanarum et divinarum libri XLI

- Logistoricon libri LXXVI

- Hebdomades vel de imaginibus

- Disciplinarum libri IX (An encyclopedia on the liberal arts, of which the first book dealt with grammar)

- De rebus urbanis libri III (or On Urban Topics in Three Books)

- De gente populi Romani libri IIII (cf. Augustine, 'De civitate dei' xxi. 8.)

- De sua vita libri III (or On His Own Life in Three Books)

- De familiis troianis (or On the Families of Troy)

- De Antiquitate Litterarum libri II (addressed to the tragic poet Lucius Accius; it is therefore one of his earliest writings)

- De Origine Linguae Latinae libri III (addressed to Pompey; cf. Augustine, 'De civitate dei' xxii. 28.)

- Περί Χαρακτήρων (in at least three books, on the formation of words)

- Quaestiones Plautinae libri V (containing interpretations of rare words found in the comedies of Plautus)

- De Similitudine Verborum libri III (on regularity in forms and words)

- De Utilitate Sermonis libri IIII (on the principle of anomaly or irregularity)

- De Sermone Latino libri V (?) (addressed to Marcellus,[13] on orthography and the metres of poetry)

- De philosophia (cf. Augustine, 'De civitate dei' xix. 1.)

Most of the extant fragments of these works (mostly the grammatical works) can be found in the Goetz–Schoell edition of De Lingua Latina, pp. 199–242; in the collection of Wilmanns, pp. 170–223; and in that of Funaioli, pp. 179–371.

References

- ↑ "Marcus Terentius Varro | Roman author". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2017-01-12.

- ↑ "LacusCurtius • Varro On Agriculture — Book I". penelope.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 2017-01-12.

- 1 2 Baynes, Thomas Spencer (1891-01-01). The Encyclopaedia Britannica: A Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, and General Literature. C. Scribner's sons.

- ↑ Caesar; Damon, Cynthia (2016-05-23). Civil War. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674997035.

- ↑ Prioreschi, Plinio (1996-01-01). A History of Medicine: Roman medicine. Horatius Press. ISBN 9781888456035.

- 1 2 Lindberg, David (2007). The Beginnings of Western Science. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 137. ISBN 0-226-48205-7. Retrieved 6 March 2010.

- ↑ Quintilian. "Chapter 1". Institutio Oratoria. Book X. Verse 95.

- ↑ Harrison, Fairfax (1918). "Note Upon the Roman Agronomists". Roman Farm Management. New York: The Macmillan Company. pp. 1–14 [10].

- ↑ Varro, Marcus Terentius (16 September 2014) [1934]. De Re Rustica. Loeb Classical Library. I.12.2 – via Bill Thayer's Website.

- ↑ Thompson, Sue (March 2014). "From Ground to Tap" (PDF). The Mole. Royal Society of Chemistry: 3 (sidebar). Archived from the original on 12 October 2014. Retrieved August 21, 2017.

- ↑ Hempelmann, Ernst; Krafts, Kristine (October 2013). "Bad Air, Amulets and Mosquitoes: 2,000 Years of Changing Perspectives on Malaria". Malaria Journal. 12: 232. doi:10.1186/1475-2875-12-232. ISSN 1475-2875. Retrieved August 21, 2017.

- ↑ Wilmanns, Augustus (1864). "II:97". De M. Terenti Varronis Libris Grammaticis. Gutenberg. Berlin: Weidmann.

Marcellus autem ad quem haec uolumina misit quis fuerit nescio.

- ↑ Several people called Marcellus lived during Varro's time. The identity of this one is unclear.[12]

Further reading

- Cardauns, B. Marcus Terentius Varro: Einführung in sein Werk. Heidelberger Studienhefte zur Altertumswissenschaft. Heidelberg, Germany: C. Winter, 2001.

- d’Alessandro, P. Varrone e la tradizione metrica antica. Spudasmata, Bd. 143. Hildesheim; Zürich; New York: Georg Olms Verlag, 2012.

- Dahlmann, H. M. Terentius Varro. Paulys Realencyclopädie der classischen Altertumswissenschaft. Supplement 6, Abretten bis Thunudromon. Edited by Wilhelm Kroll, 1172–1277. Stuttgart: Metzler, 1935.

- Ferriss-Hill, J. “Varro’s Intuition of Cognate Relationships.” Illinois Classical Studies, vol. 39, 2014, pp. 81-108.

- Freudenburg, K. "The Afterlife of Varro in Horace's Sermones: Generic Issues in Roman Satire." Generic Interfaces in Latin Literature: Encounters, Interactions and Transformations, edited by Stavros Frangoulidis, De Gruyter, 2013, pp. 297-336.

- Kronenberg, L. Allegories of Farming from Greece and Rome: Philosophical Satire in Xenophon, Varro and Virgil. Cambridge/New York: Cambridge University Press, 2009.

- Nelsestuen, G. Varro the Agronomist: Political Philosophy, Satire, and Agriculture in the Late Republic. Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 2015.

- Richardson, J. S. “The Triumph of Metellus Scipio and the Dramatic Date of Varro, RR 3.” The Classical Quarterly, vol. 33, no. 2, 1983, pp. 456–463.

- Taylor, D. J.. Declinatio : A Study of the Linguistic Theory of Marcus Terentius Varro. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company, 1974.

- Van Nuffelen, P. “Varro’s Divine Antiquities: Roman Religion as an Image of Truth.” Classical Philology, vol. 105, no. 2, 2010, pp. 162–188.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Marcus Terentius Varro |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Marcus Terentius Varro |

| Library resources about Varro |

| By Varro |

|---|

- Works by Marcus Terentius Varro at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Marcus Terentius Varro at Internet Archive

- Works by Marcus Terentius Varro at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- de Re Rustica (Latin and English at LacusCurtius)

- Links to translation of De Linga Latina by R.G.Kent

- Livius.org: Varronian chronology

- thelatinlibrary.com: Latin works of Varro