Maragheh observatory

Maragheh observatory (Persian: رصدخانه مراغه), was an institutionalized astronomical observatory which was established in 1259 CE under the patronage of the Ilkhanid Hulagu and the directorship of Nasir al-Din al-Tusi, a Persian scientist and astronomer. Located in the heights west of Maragheh, which is today situated in the East Azerbaijan Province of Iran, it was once considered "the most advanced scientific institution in the Eurasian world".[1]

It was financed by waqf revenues, which allowed it to continue to operate even after the death of its founder and was active for more than 50 years. The observatory served as a model for later observatories including the 15th-century Ulugh Beg Observatory in Samarkand, the 16th-century Taqi al-Din observatory in Constantinople, and the 18th-century Jai Singh observatory in Jaipur.[2]

Description

Considerable parts of the groundwork are preserved in the ruins. In a 340 times 135 m citadel-like area stood a four-story circular stone building of 28 m diameter. The mural quadrant to observe the positions of the stars and planets was aligned with the meridian. This meridian served as prime meridian for the tables in the Zij-i Ilkhani, as we nowadays apply the meridian which passes the Royal Greenwich Observatory.

History

When Tusi complained that his astronomical tables had to be adapted to the latitude and longitude of Hulagu's new capital[3], Hulagu gave a permission to build a new observatory in a place of Tusi's choice. According to books like Jam-e-ttavarikhe rashidi (Persian: جامع التواريخ رشيدي), saf-e-elhofreh (Persian: صاف الحفره), favat-o-lvafiyyat (Persian: فوات الوفيات) the building of the rasad khaneh started in 1259 (657 A.H.). The library of the observatory contained 40,000 books on many subjects, related to astrology/astronomy as well as other topics. Bar-Hebraeus late in his life took residence close to the observatory in order to use the library for his studies. He has left a description of the observatory.

A number of other prominent astronomers worked with Tusi there, such as Muhyi al-Din al-Maghribi, Mu'ayyid al-Din al-'Urdi, from Damascus, Qutb al-Din al-Shirazi, and Hulagu's Chinese astronomer Fao Munji whose Chinese astronomical experience brought improvements to Ptolemaic system used by Tusi.

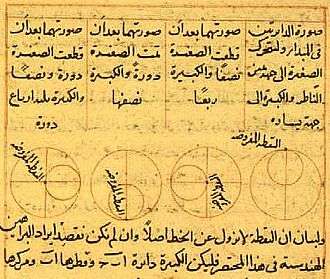

For his planetary models, Tusi invented a geometrical technique called a Tusi-couple, which generates linear motion from the sum of two circular motions. He also determined the precise value of 51 arcsec for the annual precession of the equinoxes and contributed to the construction and usage of some astronomical instruments including the astrolabe.

And after 12 years of intense work by Khaje Nassir od-Din Tussi and the other prominent scientists the observations and planetary models were compiled in the Zij-i Ilkhani, which later still might have influenced Copernicus. The tables were published during the reign of Abaqa Khan, Hulagu's son, and named after the patron of the observatory. They were popular until the 15th century.

It is not known with certainty until when it had been active. It turned into ruins as a result of frequent earthquakes and lack of funding by the state. Shah Abbas the Great arranged for repair, however, this was not commenced due to the king's early death.

The remains inspired Ulugh Beg to construct his observatory in Samarkand in 1428.

Hulagu's older brother, Khublai Khan also constructed an observatory, the Gaocheng Astronomical Observatory in China.

A celestial globe from the observatory made around 1279 is now preserved in Dresden, Germany. It is a rare example of decorative art from Iran of the 13th century, designed by al-Urdi and made of bronze, inlaid with silver and gold.

Current status

To save the installation from further destruction, Cultural Heritage Organization of Iran built a dome-framed shelter and it plans to hold an exhibit of astronomical devices used at Maragheh observatory.

The observatory is currently covered with a dome-framed brass structure and is situated two miles west of Maragheh.

Notes

- ↑ Blake, Stephen P. (2016). "The observatory in Maragha". Astronomy and Astrology in the Islamic World. Edinburgh University Press. p. 65. ISBN 978-0748649112.

In the history of Islamic astronomy the thirteenth century was the most important. It witnessed the founding of the Maragha Observatory, the most advanced scientific institution in the Eurasian world.

- ↑ Dallal, Ahmad (2010). Islam, science, and the challenge of history. Yale University Press. pp. 24–25. ISBN 9780300159110.

- ↑ S. Frederick Starr (2013): Lost Enlightenment, Princeton University Press, page 460

References

- A. Baker and L. Chapter (2002), "Part 4: The Sciences". In M. M. Sharif, "A History of Muslim Philosophy", Philosophia Islamica.

- Richard Covington (May–June 2007). "Rediscovering Arabic science", Saudi Aramco World, p. 2-16.

- Ahmad Dallal, "Science, Medicine and Technology.", in The Oxford History of Islam, ed. John Esposito, New York: Oxford University Press, (1999).

- Morelon, Régis; Rashed, Roshdi (1996), Encyclopedia of the History of Arabic Science, 3, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-12410-7

- George Saliba (1999). Whose Science is Arabic Science in Renaissance Europe? Columbia University.

External links

- Maragheh observatory at Iranian Cultural Heritage Organization Documentation Center

- Research Institute for Astronomy and Astrophysics of Maragha

- On Maragheh observatory at RIAAM

- Contribution by Parviz Tarikhi with illustrations

- Inside the protecting dome

- Copy of the celestial globe

- Al-Urdi's Article on 'The Quality of Observation', FSTC Limited

- Tishineh

Coordinates: 37°23′45.88″N 46°12′32.97″E / 37.3960778°N 46.2091583°E