The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance

| The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance | |

|---|---|

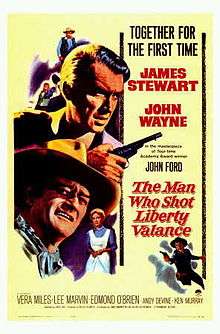

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | John Ford |

| Produced by |

|

| Written by |

|

| Based on |

A 1953 short story by Dorothy M. Johnson |

| Starring | |

| Music by | |

| Cinematography | William H. Clothier |

| Edited by | Otho Lovering |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Paramount Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 123 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $3.2 million |

| Box office | $8 million[2] |

The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (/ˈvæləns/) is a 1962 American western film directed by John Ford starring James Stewart and John Wayne. The black-and-white film was released by Paramount Pictures. The screenplay by James Warner Bellah and Willis Goldbeck was adapted from a short story written by Dorothy M. Johnson. The supporting cast features Vera Miles, Lee Marvin, Edmond O'Brien, Andy Devine, John Carradine, Woody Strode, Strother Martin, and Lee Van Cleef.

In 2007, the film was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant."

Plot summary

Senator Ranse Stoddard and his wife Hallie arrive in Shinbone, a frontier town in an unnamed western state, to attend the funeral of Tom Doniphon. As they pay their respects, reporters ask Stoddard why a United States Senator would make the long journey from Washington to attend the funeral of a local rancher.

The story flashes back 25 years; Stoddard is a young, idealistic attorney. His stagecoach is robbed by Liberty Valance and his gang. When Stoddard tries to take Valance to task, Stoddard is brutally whipped and left for dead. Doniphon finds him and takes him into the town of Shinbone; Hallie and other townspeople tend to his injuries, and explain that Valance victimizes Shinbone residents with impunity. Marshal Link Appleyard lacks the courage and gunfighting skills to challenge him. Doniphon (who is courting Hallie) is the only man willing to stand up to him.

Stoddard opens a law practice in Shinbone, inviting retribution from Valance, who cannot abide challenges to his "authority." Force, Doniphon explains, is the only thing Valance understands; but Stoddard advocates justice under the law, not brute force. He earns the town's respect by refusing to knuckle under to Valance, and by founding a school to teach reading and writing to illiterate townspeople – including Hallie. Hallie discovers Stoddard is practicing with a gun, and fretfully tells Doniphon, which raises his suspicions about their relationship.

When Doniphon notices that Stoddard is trying to teach himself to use a revolver, he offers the inexperienced Stoddard a lesson in marksmanship. During target practice Doniphon effortlessly shoots three paint cans; the final one showers Stoddard with white paint, ruining his suit. Tom explains that this is the sort of trickery that he can expect from Valance. Infuriated, Stoddard punches him in the jaw and leaves.

Shinbone's residents meet to elect two delegates for a statehood convention at the territorial capital. Doniphon nominates Stoddard, because he "knows the law, and throws a mean punch." Stoddard explains that statehood will improve infrastructure, safety, and education. The cattle barons oppose statehood, and hire Valance to sabotage the effort, but Stoddard defies him again. The townspeople elect Stoddard and Dutton Peabody, publisher of the local newspaper; Valance challenges Stoddard to a gunfight. Doniphon advises Stoddard to leave town, but Stoddard believes in the rule of law, and is willing to risk his life for his principles.

That evening, Valance and his gang catch the drunken Peabody, beat him nearly to death and ransack his office. Stoddard goes into the street to face Valance. Valance toys with Stoddard, shooting his arm and laughing at him. The next bullet, he says, will be "right between the eyes"; but Stoddard fires first, and to everyone's shock, Valance falls dead. Doniphon watches Hallie care for Stoddard's wounds, then heads for the saloon. At his homestead, in a drunken rage, he sets fire to the addition that he has just finished in anticipation of asking Hallie to marry him. His African American ranch hand, Pompey, rescues him, but the house is destroyed.

At the statehood convention, Peabody nominates Stoddard as the territory's delegate to Washington, D.C., but his "unstatesmanlike" conduct is challenged by a rival candidate. Stoddard decides that he cannot be entrusted with public service after killing a man in a gunfight. Doniphon takes him aside and, in an flashback within a flashback, confides that he, Doniphon, actually killed Valance from an alley across the street, firing at the same time as Stoddard. Reinspired, Stoddard returns to the convention, accepts the nomination, and is elected to the Washington delegation.

The original flashback ends; Stoddard fills in the intervening years. He married Hallie, and then, on the strength of his reputation as "the man who shot Liberty Valance", became the new state's first governor. He then served as U.S. Senator and United States Ambassador to the United Kingdom before returning to the Senate, and now there is talk of a vice presidential nomination. The reporter realizes that Stoddard's entire reputation is based on a myth; but after reflection, he throws his interview notes into the fire. "This is the West, sir," he explains. "When the legend becomes fact, print the legend."

On the train back to Washington, Stoddard informs Hallie, to her delight, that he wants to retire from politics and practice law in Shinbone. When he tells the train conductor that he will write to railroad officials, thanking them for their many courtesies, the conductor replies, "Nothing's too good for the man who shot Liberty Valance!"

Cast

|

|

|

Production

In contrast to prior John Ford westerns, such as The Searchers and She Wore a Yellow Ribbon, Liberty Valance was shot in black and white on Paramount's sound stages. Multiple stories and speculations exist to explain this decision. Ford claimed to prefer the black and white medium over color: "In black and white, you've got to be very careful. You've got to know your job, lay your shadows in properly, get your perspective right, but in color, there it is," he said. "You might say I'm old fashioned, but black and white is real photography."[3] Ford also reportedly argued that the climactic shoot-out between Valance and Stoddard would not have worked in color.[4] Others have interpreted the absence of the magnificent outdoor vistas so prevalent in earlier Ford westerns as "a fundamental reimagining [by Ford] of his mythic West" – a grittier, less romantic, more realistic portrayal of frontier life.[5] A more pragmatic interpretation cites the fact that Wayne and Stewart – two of Hollywood's biggest stars, working together for the first time – were considerably older (54 and 53, respectively) than the characters they were playing. Filming in black and white helped ease the suspension of disbelief necessary to accept that disparity.[6] According to cinematographer William H. Clothier, however, "There was one reason and one reason only ... Paramount was cutting costs. Otherwise we would have been in Monument Valley or Brackettville and we would have had color stock. Ford had to accept those terms or not make the film."[7]

Another condition imposed by the studio, according to Van Cleef, was that Wayne be cast as Doniphon. Ford resented the studio's intrusion, and retaliated by taunting Wayne relentlessly throughout the filming. "He didn't want Duke [Wayne] to think he was doing him any favors," Van Cleef said.[8] Strode recounted that Ford "kept needling Duke about his failure to make it as a football player", comparing him to Strode (a former NFL running back), whom he pronounced "a real football player". (Wayne's football career at USC had been curtailed by injuries.) He also ridiculed Wayne for failing to enlist during World War II, during which Ford filmed a series of widely praised combat documentaries for the Office of Strategic Services, and was wounded at the Battle of Midway,[9] and Stewart served with distinction as a bomber pilot and commanded a bomber group. "How rich did you get while Jimmy was risking his life?" he demanded. Wayne's avoidance of wartime service was a major source of guilt for him in his later years.[10]

Stewart related that midway through filming, Wayne asked him why he, Stewart, never seemed to be the target of Ford's venomous remarks. Other cast- and crew-members also noticed Stewart's apparent immunity from Ford's abuse. Then, toward the end of filming, Ford asked Stewart what he thought of Strode's costume for the film's beginning and end, when the actors were playing their parts 25 years older. Stewart replied, "It looks a bit Uncle Remussy to me." Ford responded, "What's wrong with Uncle Remus?" He called for the crew's attention and announced, "One of our players doesn't like Woody's costume. Now, I don't know if Mr. Stewart has a prejudice against Negroes, but I just wanted you all to know about it." Stewart said he "wanted to crawl into a mouse hole"; but Wayne told him, "Well, welcome to the club. I'm glad you made it."[8][11]

Ford's behavior "...really pissed Wayne off," Strode said, "but he would never take it out on Ford," the man largely responsible for his rise to stardom. "He ended up taking it out on me." While filming an exterior shot on a horse-drawn cart, Wayne almost lost control of the horses, and knocked Strode away when he attempted to help. When the horses did stop, Wayne tried to pick a fight with the younger and fitter Strode; Ford called out, "Don't hit him, Woody, we need him." Wayne later told Strode, "We gotta work together. We both gotta be professionals." Strode blamed Ford for nearly all the friction on the set. "What a miserable film to make," he added.[12]

Stewart received top billing over Wayne on promotional posters, but in the film itself Wayne's screen card appears first. The studio also specified that Wayne's name appear before Stewart's on theatre marquees, reportedly at Ford's request.[13] "Wayne actually played the lead," Ford said, to Peter Bogdanovich. "Jimmy Stewart had most of the sides [sequences with dialogue], but Wayne was the central character, the motivation for the whole thing."[14]

Parts of the film were shot in Wildwood Regional Park in Thousand Oaks, California.[15][16]

Music

The film's music score was composed by Cyril J. Mockridge; but in scenes involving Hallie's relationships with Doniphon and Stoddard, Ford reprised Alfred Newman's "Ann Rutledge Theme", from Young Mr. Lincoln. He told Bogdanovich that he used the theme in both films to evoke repressed desire and lost love.[17] The film scholar Kathryn Kalinak notes that Ann Rutledge's theme "encodes longing" and "fleshes out the failed love affair between Hallie and Tom Doniphon, the growing love between Hallie and Ranse Stoddard, and the traumatic loss experienced by Hallie over her choice of one over the other, none of which is clearly articulated by dialogue."[18]

The Burt Bacharach-Hal David song "(The Man Who Shot) Liberty Valance" became a Top 10 hit for Gene Pitney. Though based upon the movie's plotline, it was not used in the film. Pitney said in an interview that he was in the studio about to record the song when "... Bacharach informed us that the film just came out." Regardless, the song went to No. 4.[19] Jimmie Rodgers also recorded the song, in the Gene Pitney style. James Taylor covered it on his 1985 album That's Why I'm Here, as did The Royal Guardsmen on their 1967 album Snoopy vs. the Red Baron. It was also covered by the Australian rock band Regurgitator on its 1998 David/Bacharach tribute album To Hal and Bacharach. Members of the Western Writers of America chose it as one of the top 100 Western songs of all time.[20]

Reception

Liberty Valance was released in April 1962, and achieved both financial and critical success. Produced for $3.2 million, it grossed $8 million,[2] making it the 16th highest-grossing film of 1962. Edith Head's costumes were nominated for an Academy Award for Best Costume Design (black-and-white), one of the few westerns ever nominated in that category.[21]

Contemporary reviews were generally positive, although a number of critics thought the final act was a letdown. Variety called the film "entertaining and emotionally involving," but thought if the film had ended twenty minutes earlier, "it would have been a taut, cumulative study of the irony of heroic destiny," instead of concluding with "condescending, melodramatic, anti-climactic strokes. What should have been left to enthrall the imagination is spelled out until there is nothing left to savor or discuss."[22] The Monthly Film Bulletin agreed, lamenting that the "final anti-climactic twenty minutes ... all but destroy the value of the disarming simplicity and natural warmth which are Ford's everlasting stock-in-trade." Despite this, the review maintained that the film "has more than enough gusto to see it through," and that Ford had "lost none of his talent for catching the real heart, humour and violent flavour of the Old West in spite of the notable rustiness of his technique."[23] A. H. Weiler of The New York Times wrote that "Mr. Ford, who has struck more gold in the West than any other film-maker, also has mined a rich vein here," but opined that the film "bogs down" once Stoddard becomes famous, en route to "an obvious, overlong and garrulous anticlimax."[24] Richard L. Coe of The Washington Post called the film "a leisurely yarn boasting fine performances," but was bothered by "the incredulous fact that the lively townsfolk of Shinbone didn't polish off Valence [sic] for themselves. On TV he would have been dispatched by the second commercial and the villainy would have passed to some shadowy employer, some ruthless rancher who didn't want statehood."[25] John L. Scott of the Los Angeles Times wrote, "Director Ford is guilty of a few lengthy, slow periods in his story-telling, but for the most part the old, reliable Ford touches are there."[26] Harrison's Reports gave the film a grade of "Very Good,"[27] but Brendan Gill of The New Yorker was negative and called it "a parody of Mr. Ford's best work."[28]

More recent assessments have been more uniformly positive. The film is considered one of Ford's best[29] and, in one poll, ranked with The Searchers and The Shootist as one of Wayne's best westerns.[30]

Roger Ebert wrote that each of the ten Ford/Wayne westerns is "... complete and self-contained in a way that approaches perfection", and singled out Liberty Valance as "the most pensive and thoughtful" of the group.[31] Director Sergio Leone (Once Upon a Time in the West, The Good, the Bad and the Ugly) listed Ford as a major influence on his work, and Liberty Valance as his favorite Ford film. "It was the only film," he said, "where [Ford] learned about something called pessimism."[32]

In a retrospective analysis, The New York Times called Liberty Valance "...one of the great Western classics," because "it questions the role of myth in forging the legends of the West, while setting this theme in the elegiac atmosphere of the West itself, set off by the aging Stewart and Wayne."[33] The New Yorker's Richard Brody described it as "the greatest American political movie", because of its depictions of a free press, town meetings, statehood debates, and the "civilizing influence" of education in frontier America.[31]

The film is recognized by American Film Institute in these lists:

- 2003: AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes & Villains:

- Tom Doniphon – Nominated Hero[34]

- 2005: AFI's 100 Years...100 Movie Quotes:

- Maxwell Scott: "This is the West, sir. When the legend becomes fact, print the legend." – Nominated[35]

- 2008: AFI's 10 Top 10:

- Nominated Western Film[36]

See also

References

- ↑ "This Week's Movie Openings". Los Angeles Times: Calendar, p. 18. April 15, 1962.

- 1 2 "Box Office Information for The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance". The Numbers. Retrieved June 13, 2013.

- ↑ McBride (2003), p. 306

- ↑ Kalinak (2007), p. 96

- ↑ Coursen, D. (May 21, 2009). "John Ford's Wilderness: The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance". Parallax View. Retrieved September 10, 2014.

- ↑ McBride (2003), p. 312

- ↑ Munn (2004), p. 232

- 1 2 Munn (2004), p. 233

- ↑ "A Look Back ... John Ford: War Movies". cia.gov. Retrieved December 1, 2014.

- ↑ Wayne, Pilar. John Wayne. pp. 43–47.

- ↑ McBride (2003), p. 631

- ↑ Munn (2004), p. 234

- ↑ Matthews, L. (1984). History of Western Movies. Crescent. p. 132. ISBN 0517414759.

- ↑ Bogdanovich (1978), p. 99

- ↑ Schneider, Jerry L. (2015). Western Filming Locations Book 1. CP Entertainment Books. Page 116. ISBN 9780692561348.

- ↑ Fleming, E.J. (2010). The Movieland Directory: Nearly 30,000 Addresses of Celebrity Homes, Film Locations and Historical Sites in the Los Angeles Area, 1900–Present. McFarland. Page 48. ISBN 9781476604329.

- ↑ Bogdanovich (1978), pp. 95-96

- ↑ Kalinak (2007), pp. 96-98.

- ↑ Sisario, Ben (April 6, 2006). "Gene Pitney, Who Sang of 60's Teenage Pathos, Dies at 65". The New York Times.

- ↑ Western Writers of America (2010). "The Top 100 Western Songs". American Cowboy. Archived from the original on 10 August 2014.

- ↑ "The 35th Academy Awards (1963) Nominees and Winners". Oscars.org. Retrieved September 15, 2014.

- ↑ "The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance". Variety: 6. April 11, 1962.

- ↑ "The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance". The Monthly Film Bulletin. 29 (341): 78. June 1962.

- ↑ Weiler, A. H. (May 24, 1962). "'Man Who Shot Liberty Valance' Opens at Capitol Theatre". The New York Times: 29.

- ↑ Coe, Richard L. (April 21, 1962). "Way In Egg Role". The Washington Post: C9.

- ↑ Scott, John L. (April 20, 1962). "'Liberty Valance' Tale of Frontier Violence". Los Angeles Times: Part IV, p. 10.

- ↑ "Film Review: 'The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance'". Harrison's Reports: 58. April 21, 1962.

- ↑ Gill, Brendan (June 16, 1962). "The Current Cinema". The New Yorker: 102.

- ↑ "Top 7 John Ford films (because we couldn't pick just 5)". movie mail.com. Retrieved September 15, 2014.

- ↑ "Readers suggest the 10 best westerns". guardian.com archive. Retrieved September 15, 2014.

- 1 2 Ebert, Roger (December 28, 2011). "The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance". rogerebert.com archive. Retrieved September 15, 2014.

- ↑ Nixon, R. "The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance". Turner Classic Movies archive. Retrieved September 15, 2014.

- ↑ Erickson, H. "The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance". New York Times archive. Retrieved September 15, 2014.

- ↑ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes & Villains Nominees" (PDF). Retrieved 2016-08-06.

- ↑ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Movie Quotes Nominees" (PDF). Retrieved 2016-08-06.

- ↑ "AFI's 10 Top 10 Nominees" (PDF). Archived from the original on 2011-07-16. Retrieved 2016-08-19.

Sources

- Bogdanovich, P. (1978). John Ford. University of California Press. ISBN 0520034988.

- Kalinak, K. (2007). How the West Was Sung: Music in the Westerns of John Ford. University of California Press. ISBN 0520252349.

- McBride, Joseph (2003). Searching For John Ford: A Life. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-31011-0.

- Munn, Michael (2004). John Wayne — The Man Behind The Myth. Robson Books.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance |