Liberal arts education

Liberal arts education (from Latin liberalis "free" and ars "art or principled practice") can claim to be the oldest programme of higher education in Western history.[1] It has its origin in the attempt to discover first principles – 'those universal principles which are the condition of the possibility of the existence of anything and everything'.[2] The liberal arts are those subjects or skills that in classical antiquity were considered essential for a free person (liberalis, "worthy of a free person")[3] to know in order to take an active part in civic life, something that (for ancient Greece) included participating in public debate, defending oneself in court, serving on juries, and most importantly, military service. Grammar, logic, and rhetoric were the core liberal arts (the trivium), while arithmetic, geometry, the theory of music, and astronomy also played a – somewhat lesser – part in education (as the quadrivium).[4]

Liberal arts today can refer to academic subjects such as literature, philosophy, mathematics, and social and physical sciences;[5] and liberal arts education can refer to overall studies in a liberal arts degree program. For both interpretations, the term generally refers to matters not relating to the professional, vocational, or technical curriculum.

History

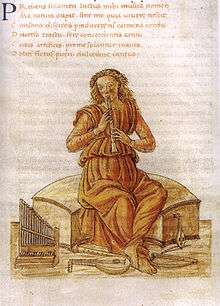

Rooted in the basic curriculum – the enkuklios paideia or "education in a circle" – of late Classical and Hellenistic Greece, the "liberal arts" or "liberal pursuits" (Latin liberalia studia) were already so called in formal education during the Roman Empire. The first recorded use of the term "liberal arts" (artes liberales) occurs in De Inventione by Marcus Tullius Cicero, but it is unclear if he created the term.[6][7] Seneca the Younger discusses liberal arts in education from a critical Stoic point of view in Moral Epistles.[8] The exact classification of the liberal arts varied however in Roman times,[9] and it was only after Martianus Capella in the 5th century AD influentially brought the seven liberal arts as bridesmaids to the Marriage of Mercury and Philology,[10] that they took on canonical form.

The four 'scientific' artes – music, arithmetic, geometry and astronomy (or astrology) – were known from the time of Boethius onwards as the quadrivium. After the 9th century, the remaining three arts of the 'humanities' – grammar, logic, and rhetoric – were grouped as the trivium.[9] It was in that two-fold form that the seven liberal arts were studied in the medieval Western university.[11][12] During the Middle Ages, logic gradually came to take predominance over the other parts of the trivium.[13]

In the Renaissance, the Italian humanists and their Northern counterparts, despite in many respects continuing the traditions of the Middle Ages, reversed that process.[14] Re-christening the old trivium with a new and more ambitious name: Studia humanitatis, and also increasing its scope, they downplayed logic as opposed to the traditional Latin grammar and rhetoric, and added to them history, Greek, and moral philosophy (ethics), with a new emphasis on poetry as well.[15] The educational curriculum of humanism spread throughout Europe during the sixteenth century and became the educational foundation for the schooling of European elites, the functionaries of political administration, the clergy of the various legally recognized churches, and the learned professions of law and medicine.[16] The ideal of a liberal arts, or humanistic education grounded in classical languages and literature, persisted until the middle of the twentieth century.[17]

Modern usage

Some subsections of the liberal arts are in the trivium—the verbal arts: grammar, logic, and rhetoric; and in the quadrivium—the numerical arts: music, and astronomy. Analyzing and interpreting information is also included.

Academic areas that are associated with the term liberal arts include:

- Arts (fine arts, music, performing arts, literature)

- Philosophy

- Religious studies

- Social science (anthropology, geography, history, jurisprudence, linguistics, political science, psychology, sociology)

- Mathematics

- Natural Sciences (biology, chemistry, physics, astronomy, earth sciences)

For example, the core courses for Georgetown University's Doctor of Liberal Studies program[18] cover philosophy, theology, history, art, literature, and the social sciences. Wesleyan University's Master of Arts in Liberal Studies program includes courses in visual arts, art history, creative and professional writing, literature, history, mathematics, film, government, education, biology, psychology, and astronomy.[19]

Secondary school

The liberal arts education at the secondary school level prepares the student for higher education at a university. They are thus meant for the more academically minded students. In addition to the usual curriculum, students of a liberal arts education often study Latin and Ancient Greek.

Some liberal arts education provide general education, others have a specific focus. (This also differs from country to country.) The four traditional branches are:

- humanities education (specializing in classical languages, such as Latin and Greek)

- modern languages (students are required to study at least three languages)

- lower level mathematical-scientific education

- economical and social-scientific education (students are required to study simple economics, world history, social studies and business informatics)

Curricula differ from school to school, but generally include language, mathematics, informatics, physics, chemistry, biology, geography, art (as well as crafts and design), music, history, philosophy, civics / citizenship,[20] social sciences, and several foreign languages.

Schools concentrate not only on academic subjects, but on producing well-rounded individuals, so physical education and religion or ethics are compulsory, even in non-denominational schools which are prevalent. For example, the German constitution guarantees the separation of church and state, so although religion or ethics classes are compulsory, students may choose to study a specific religion or none at all.

Today, a number of other areas of specialization exist, such as gymnasiums specializing in economics, technology or domestic sciences. Some countries also have progymnasiums, which may lead to studying in a gymnasium.

In the United States

In the United States, liberal arts colleges are schools emphasizing undergraduate study in the liberal arts.[21] The teaching at liberal arts colleges is often Socratic, typically with small classes, and often has a lower student-to-teacher ratio than at large universities; professors teaching classes are often allowed to concentrate more on their teaching responsibilities than primary research professors or graduate student teaching assistants at universities. Dartmouth College is a well-known liberal arts college, in addition to several small liberal arts colleges in the northeastern part of the United States.

In addition, most four-year colleges are not devoted exclusively or primarily to liberal arts degrees, but offer a liberal arts degree, and allow students not majoring in liberal arts to take courses to satisfy distribution requirements in liberal arts.

Traditionally, a bachelor's degree either in liberal arts in general or in one particular area within liberal arts, with substantial study outside that main area, is earned over four years of full-time study. However, some universities such as Saint Leo University,[22] Pennsylvania State University,[23] Florida Institute of Technology[24] and New England College[25] have begun to offer an associate degree in liberal arts. Colleges like New Saint Andrews College in Moscow, Idaho, offer a unique program with only one degree offering, a Bachelor of Arts in Liberal Studies, and colleges like the University of Oklahoma College of Liberal Studies offers an online, part-time option for adult and nontraditional students.

Most students earn either a Bachelor of Arts degree or a Bachelor of Science[26] degree; on completing undergraduate study, students might progress to either a liberal arts graduate school or a professional school (public administration, engineering, business, law, medicine, theology).

In Europe

In most parts of Europe, liberal arts education is deeply rooted. In Germany, Austria and countries influenced by their education system it is called 'humanistische Bildung' (humanistic education). The term is not to be mixed up with some modern educational concepts that use a similar wording. Educational institutions that see themselves in that tradition are often a Gymnasium" (high school, grammar school). They aim at providing their pupils with comprehensive education (Bildung) in order to form personality with regard to a pupil's own humanity as well as their innate intellectual skills. Going back to the long tradition of the liberal arts in Europe, education in the above sense was freed from scholastic thinking and re-shaped by the theorists of the Enlightenment; in particular, Wilhelm von Humboldt. Since students are considered to have received a comprehensive liberal arts education at gymnasiums, very often the role of liberal arts education in undergraduate programs at universities is reduced compared to the US educational system. Students are expected to use their skills received at the gymnasium in order to further develop their personality in their own responsibility, e.g. in universities' music clubs, theatre groups, language clubs, etc. Universities encourage students to do so and offer respective opportunities but do not make such activities part of the university's curriculum.

Thus, on the level of higher education, despite the European origin of the liberal arts college,[27] the term liberal arts college usually denotes liberal arts colleges in the United States. With the exception of pioneering institutions such as Franklin University Switzerland (formerly known as Franklin College), established as a Europe-based, US-style liberal arts college in 1969,[28] only recently some efforts have been undertaken to systematically "re-import" liberal arts education to continental Europe, as with Leiden University College The Hague, University College Utrecht, University College Maastricht, Amsterdam University College, Roosevelt Academy (now University College Roosevelt), ATLAS University College, Erasmus University College, the University of Groningen, Bratislava International School of Liberal Arts, and Bard College Berlin, formerly known as the European College of Liberal Arts. As well as the colleges listed above, some universities in the Netherlands offer bachelors programs in Liberal Arts and Sciences (Tilburg University). Liberal arts (as a degree program) is just beginning to establish itself in Europe. For example, University College Dublin offers the degree, as does St. Marys University College Belfast, both institutions coincidentally on the island of Ireland. In the Netherlands, universities have opened constituent liberal arts colleges under the terminology university college since the late 1990s. The four-year bachelor's degree in Liberal Arts and Sciences at University College Freiburg is the first of its kind in Germany. It started in October 2012 with 78 students.[29] The first Liberal Arts degree program in Sweden was established at Gothenburg University in 2011,[30] followed by a Liberal Arts Bachelor Programme at Uppsala University's Campus Gotland in the autumn of 2013.[31] The first Liberal Arts program in Georgia was introduced in 2005 by American-Georgian Initiative for Liberal Education (AGILE),[32] an NGO. Thanks to their collaboration, Ilia State University[33] became the first higher education institution in Georgia to establish a liberal arts program.[34]

In France, Chavagnes Studium, a Liberal Arts Study Centre in partnership with the Institut Catholique d'études supérieures, and based in a former Catholic seminary, is launching a two-year intensive BA in the Liberal Arts, with a distinctively Catholic outlook.[35] It has been suggested that the liberal arts degree may become part of mainstream education provision in the United Kingdom, Ireland and other European countries. In 1999, the European College of Liberal Arts (now Bard College Berlin) was founded in Berlin[36] and in 2009 it introduced a four-year Bachelor of Arts program in Value Studies taught in English,[37] leading to an interdisciplinary degree in the humanities.

In England, the first institution[38] to retrieve and update a liberal arts education at the undergraduate level was the University of Winchester with their BA (Hons) Modern Liberal Arts programme which launched in 2010.[38] In 2012, University College London began its interdisciplinary Arts and Sciences BASc degree (which has kinship with the liberal arts model) with 80 students.[39] King's College London launched the BA Liberal Arts, which has a slant towards arts, humanities and social sciences subjects.[40] The New College of the Humanities also launched a new liberal education programme. The University of Nottingham has a Liberal Arts BA that provides an interdisciplinary approach, study abroad options and links with its Natural Sciences degrees.[41] In 2016, the University of Warwick launched a three/four-year liberal arts BA degree, which focuses on transdisciplinary approaches and problem-based learning techniques in addition to providing structured disciplinary pathways.[42] And for 2017 entry UCAS lists 20 providers of liberal arts programmes.[43]

In Scotland, the four-year undergraduate Honours degree, specifically the Master of Arts, has historically demonstrated considerable breadth in focus. In the first two years of Scottish MA and BA degrees students typically study a number of different subjects before specialising in their Honours years (third and fourth year). The University of Dundee and the University of Glasgow (at its Crichton Campus) are the only Scottish universities that currently offer a specifically named 'Liberal Arts' degree.

In Asia

The Commission on Higher Education of the Philippines mandates a General Education curriculum required of all higher education institutions; it includes a number of liberal arts subjects, including history, art appreciation, and ethics, plus interdisciplinary electives. Many universities have much more robust liberal arts core curricula; most notably, the Jesuit universities such as Ateneo de Manila University have a strong liberal arts core curriculum that includes philosophy, theology, literature, history, and the social sciences. Forman Christian College is a liberal arts university in Lahore, Pakistan. It is one of the oldest institutions in the Indian subcontinent. It is a chartered university recognized by the Higher Education Commission of Pakistan. Habib University in Karachi, Pakistan offers a holistic liberal arts and sciences experience to its students through its uniquely tailored liberal core program which is compulsory for all undergraduate degree students.[44][45] The Underwood International College of Yonsei University, Korea, has compulsory liberal arts course for all the student body. Symbiosis & FLAME University in Pune, Ahmedabad University, Ashoka University, Lingnan University and University of Liberal Arts- Bangladesh (ULAB) are also a few such liberal arts colleges in Asia. International Christian University in Tokyo is the first and one of the very few liberal arts universities in Japan.

In Australia

Campion College is a Roman Catholic dedicated liberal arts college, located in the western suburbs of Sydney. Founded in 2006, it is the first tertiary educational liberal arts college of its type in Australia. Campion offers a Bachelor of Arts in the Liberal Arts as its sole undergraduate degree. The key disciplines studied are history, literature, philosophy, and theology.

See also

- Artes Mechanicae – "The Mechanical Arts"

- Bachelor of General Studies

- Bachelor of Liberal Arts

- Bachelor of Liberal Studies

- College of Arts and Sciences

- Doctor of Liberal Studies

- Education reform § Reforms of classical education

- Four Arts

- Great books

- Great Books programs in Canada

- Humanitas

- Liberal arts college

- Liberal education

- List of liberal arts colleges

- Transcendentalism

References

- ↑ "What is Liberal Arts? - Ancient, Medieval, Modern - Liberal Arts UK". www.liberalarts.org.uk. Retrieved 2018-06-04.

- ↑ Nigel., Tubbs,. Philosophy and modern liberal arts education : freedom is to learn. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire. ISBN 9781137358912. OCLC 882530818.

- ↑ Ernst Robert Curtius, European Literature and the Latin Middle Ages [1948], trans. Willard R. Trask (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1973), p. 37. The classical sources include Cicero, De Oratore, I.72–73, III.127, and De re publica, I.30.

- ↑ E. B. Castle, Ancient Education and Today (1969) p. 59

- ↑ "Oxford Dictionary". The Oxford Dictionary.

- ↑ Kimball, Bruce. Orators and Philosophers. New York: College Entrance Examination Board, 1995. p. 13

- ↑ Cicero. De Inventione. Book 1, Section 35

- ↑ Ben Schneider. "Seneca – Epistle 88". Stoics.com. Retrieved 26 August 2013.

- 1 2 H. Lausberg, Handbook of Literary Rhetoric (1998) p. 10

- ↑ Helen Waddell, The Wandering Scholars (1968) p. 25

- ↑ "James Burke: The Day the Universe Changed In the Light Of the Above".

- ↑ Wagner, David Leslie (1983). The Seven liberal arts in the Middle Ages. Indiana University Press. ISBN 9780253351852. Retrieved 5 January 2013. at Questia

- ↑ Helen Waddell, The Wandering Scholars (1968) pp. 141–3

- ↑ G. Norton ed., The Cambridge History of Literary Criticism Vol 3 (1999)p. 46 and pp. 601–4

- ↑ Paul Oskar Kristeller, Renaissance Thought II: Papers on Humanism and the Arts (New York: Harper Torchbooks, 1965), p. 178.

- ↑ Charles G. Nauert, Humanism and the Culture of Renaissance Europe (New Approaches to European History) (Cambridge University Press, 2006), pp. 172–173.

- ↑ Bod, Rens; A New History of the Humanities, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2014.

- ↑ Georgetown University Doctor of Liberal Studies curriculum http://scs.georgetown.edu/departments/6/doctor-of-liberal-studies/about-the-program/curriculum#curriculum

- ↑ "Graduate Liberal Studies - Wesleyan University". www.wesleyan.edu.

- ↑ this subject has different names in the different states of Germany. See de:Gemeinschaftskunde

- ↑ "Defining Liberal Arts Education" (PDF). Wabash College. Retrieved 9 December 2012.

- ↑ "Online Liberal Arts Associate Degree". Saint Leo University. Retrieved 26 August 2013.

- ↑ "Online Associate in Arts in Letters, Arts, and Sciences | Overview". Penn State University. Retrieved 26 August 2013.

- ↑ "Associate's Degree in Liberal Arts – Liberal Arts Degree Online". Florida Institute of Technology. Retrieved 26 August 2013.

- ↑ "Associates in Liberal Studies". New England College.

- ↑ For example, Georgia Institute of Technology's bachelor of science degree in Applied Languages and Intercultural Studies http://www.modlangs.gatech.edu

- ↑ Harriman, Philip L. (1935). "Antecedents of the Liberal-Arts College". The Journal of Higher Education. Ohio State University Press. 6 (2): 63–71. doi:10.2307/1975506. ISSN 1538-4640. JSTOR 1975506 – via JSTOR. (Registration required (help)).

- ↑ "About Franklin". Franklin University Switzerland Official Web Site. Franklin University Switzerland. Archived from the original on 8 April 2014. Retrieved 2014-07-03.

- ↑ "Liberal Arts and Sciences Program (LAS)". University College Freiburg. Archived from the original on 20 August 2013. Retrieved 26 August 2013.

- ↑ "Liberal Arts, Gothenburg University". Flov.gu.se. 22 May 2013. Retrieved 26 August 2013.

- ↑ ""Liberal Arts Programme at Uppsala University"". Archived from the original on 30 June 2017. Retrieved 29 April 2018.

- ↑ "Agile". Agile.ge. Retrieved 26 August 2013.

- ↑ "ილიაუნი -მთავარი". Iliauni.edu.ge. Retrieved 26 August 2013.

- ↑ "Bachelor Degree". Iliauni. Retrieved 26 August 2013.

- ↑ "The Chavagnes Studium – Catholic Liberal Arts Centre". Chavagnes.org. 2018-03-10. Retrieved 2018-09-20.

- ↑ "Berlin's sturdiest ivory tower". Expatica.com. Retrieved 26 August 2013.

- ↑ "GERMANY: New approach to liberal studies". Universityworldnews.com. 15 March 2009. Retrieved 26 August 2013.

- 1 2 "It's the breadth that matters". 2010-12-23. Retrieved 2016-09-13.

- ↑ "Arts and Sciences (BASc) programmes". University College London. Retrieved 26 August 2013.

- ↑ "KCL – About Liberal Arts". Retrieved 15 January 2014.

- ↑ "Liberal Arts programme – BA Hons Y002 – The University of Nottingham". www.nottingham.ac.uk. Retrieved 2018-04-04.

- ↑ "Liberal Arts". www2.warwick.ac.uk.

- ↑ "UCAS Search tool – Venue Results". search.ucas.com. Retrieved 2016-09-13.

- ↑

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 2015-03-24.

Further reading

- Barzun, Jacques. The House of Intellect, Reprint Harper Perennial, 2002.

- Blaich, Charles, Anne Bost, Ed Chan, and Richard Lynch. "Defining Liberal Arts Education." Center of Inquiry in the Liberal Arts, 2004.

- Blanshard, Brand. The Uses of a Liberal Education: And Other Talks to Students. (Open Court, 1973. ISBN 0-8126-9429-5)

- Friedlander, Jack. Measuring the Benefits of Liberal Arts Education in Washington's Community Colleges. Los Angeles: Center for the Study of Community Colleges, 1982a. (ED 217 918)

- Grafton Anthony and Lisa Jardine. From Humanism to the Humanities: The Institutionalizing of the Liberal Arts in Fifteenth- and Sixteenth-century Europe, Harvard University Press, 1987.

- Guitton, Jean. A Student's Guide to Intellectual Work, The University of Notre Dame Press, 1964.

- Highet, Gilbert. The Art of Teaching, Vintage Books, 1950.

- Joseph, Sister Miriam. The Trivium: The Liberal Arts of Logic, Grammar, and Rhetoric. Paul Dry Books Inc, 2002.

- Kimball, Bruce A. The Liberal Arts Tradition: A Documentary History. University Press Of America, 2010.

- Kimball, Bruce A. Orators and Philosophers: A History of the Idea of Liberal Education. College Board, 1995.

- T. Kaori Kitao; William R. Kenan, Jr. (27 March 1999). The Usefulness Of Uselessness (PDF). Keynote Address, The 1999 Institute for the Academic Advancement of Youth's Odyssey at Swarthmore College. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 October 2008.

- McGrath, Charles. "What Every Student Should Know", New York Times, 8 January 2006.

- Parker, H. "The Seven Liberal Arts," The English Historical Review, Vol. V, 1890.

- Pfnister, Allan O. (1984). "The Role of the Liberal Arts College: A Historical Overview of the Debates". The Journal of Higher Education. Ohio State University Press. 55 (2): 145–70. doi:10.2307/1981183. ISSN 1538-4640. JSTOR 1981183 – via JSTOR. (Registration required (help)).

- Reeves, Floyd W. (1930). "The Liberal-Arts College". The Journal of Higher Education. Ohio State University Press. 1 (7): 373–80. doi:10.2307/1974170. ISSN 1538-4640. JSTOR 1974170 – via JSTOR. (Registration required (help)).

- Saint-Victor, Hugh of. The Didascalicon, Columbia University Press, 1961.

- Schall, James V. Another Sort of Learning, Ignatius Press, 1988.

- Seidel, George J. (1968). "Saving the Small College". The Journal of Higher Education. Ohio State University Press. 39 (6): 339–42. doi:10.2307/1979916. ISSN 1538-4640. JSTOR 1979916 – via JSTOR. (Registration required (help)).

- Sertillanges, A. G. The Intellectual Life, The Catholic University of America Press, 1998.

- Tubbs, N. (2011) "Know Thyself: Macrocosm and Microcosm" in Studies in Philosophy and Education Volume 30 no.1

- David L. Wagner, The Seven Liberal Arts in Middle Ages, Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1983.

- Winterer, Caroline. The Culture of Classicism: Ancient Greece and Rome in American Intellectual Life, 1780–1910. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002.

- Wriston, Henry M. The Nature of a Liberal College. Lawrence University Press, 1937.

- Zakaria, Fareed. In Defense of a Liberal Education. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2015.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Liberal education |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Liberal arts. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Seven liberal arts. |

- Fr. Herve de la Tour, "The Seven Liberal Arts", Edocere, a Resource for Catholic Education, February 2002. Thomas Aquinas's definition of and justification for a liberal arts education.

- Otto Willmann. "The Seven Liberal Arts". In The Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1907. Retrieved 13 August 2012. "[Renaissance] Humanists, over-fond of change, unjustly condemned the system of the seven liberal arts as barbarous. It is no more barbarous than the Gothic style, a name intended to be a reproach. The Gothic, built up on the conception of the old basilica, ancient in origin, yet Christian in character, was misjudged by the Renaissance on account of some excrescences, and obscured by the additions engrafted upon it by modern lack of taste . . . . That the achievements of our forefathers should be understood, recognized, and adapted to our own needs, is surely to be desired."

- "The Aim of Liberal Education", Andrew Chrucky, 1 September 2003. "The content of a liberal education should be moral problems as provided by history, anthropology, sociology, economics, and politics. And these should be discussed along with a reflection on the nature of morality and the nature of discussions, i.e., through a study of rhetoric and logic. Since discussion takes place in language, an effort should be made to develop a facility with language."

- Philosophy of Liberal Education A bibliography, compiled by Andrew Chrucky, with links to essays offering different points of view on the meaning of a liberal education.

- Mark Peltz, "The Liberal Arts and Leadership", College News (The Annapolis Group), 14 May 2012. A defense of liberal education by the Associate Dean of Grinnell College (first appeared in Inside Higher Ed).

- "Liberal Arts at the Community College", an ERIC Fact Sheet. ERIC Clearinghouse for Junior Colleges Los Angeles CA.

- "A Descriptive Analysis of the Community College Liberal Arts Curriculum". ERIC Clearinghouse for Junior Colleges Los Angeles CA

- The Center of Inquiry in the Liberal Arts. Website about The Wabash Study (for improving liberal education). Sponsored by the Center of Inquiry in the Liberal Arts at Wabash College (Indiana), the Wabash Study began in the fall of 2010 – scheduled to end in 2013. Participants include 29 prominent colleges and universities.

- Academic Commons. An online platform in support of the liberal education community. It is a forum for sharing practices, outcomes, and lessons learned of online learning. Formerly sponsored by the Center of Inquiry in the Liberal Arts, The Academic Commons is hosted by the National Institute for Technology in Liberal Education ("NITLE".).

- The Liberal Arts Advantage – for Business. Website dedicated to "Bridging the gap between business and the liberal arts". "A liberal arts education is aimed at developing the ability to think, reason, analyze, decide, discern, and evaluate. That's in contrast to a professional or technical education (business, engineering, computer science, etc.) which develops specific abilities aimed at preparing students for vocations."

- Video explanation by Professor Nigel Tubbs of liberal arts curriculum and degree requirements of Winchester University, UK.. "Liberal arts education (Latin: liberalis, free, and ars, art or principled practice) involves us in thinking philosophically across many subject boundaries in the humanities, the social and natural sciences, and fine arts. The degree combines compulsory modules covering art, religion, literature, science and the history of ideas with a wide range of optional modules. This enables students to have flexibility and control over their programme of study and the content of their assessments."

- Trivium Education. A website featuring online lectures in the liberal arts.