Léon Krier

| Léon Krier | |

|---|---|

Léon Krier at the Old Town Forum of Frankfurt, Germany, in 2007 | |

| Born |

April 7, 1946 City of Luxembourg, Grand Duchy of Luxembourg |

| Occupation | Architect |

| Awards |

Driehaus Architecture Prize 2003 Commander of the Royal Victorian Order |

Léon Krier (born 7 April 1946) is a Luxembourgish architect, architectural theorist and urban planner. He is a representative of New Urbanism and New Classical architecture. Krier was the inaugural Driehaus Architecture Prize laureate in 2003.[1] Léon Krier is the younger brother of architect Rob Krier.

Career

Krier abandoned his architectural studies at the University of Stuttgart, Germany, in 1968, after only one year, to work in the office of architect James Stirling in London, UK. After working for Stirling for three years, Krier then spent 20 years in England practicing and teaching at the Architectural Association and Royal College of Art. In this period, Krier's statement: “I am an architect, because I don’t build”,[2] became a famous expression of his uncompromising anti-modernist attitude. Between 1976 and 2016 Krier was visiting professor at the Universities of Princeton, Yale, Virginia, Cornell and Notre Dame. In 1987-90 Krier was the first director of the SOMAI, the Skidmore, Owings & Merrill Architectural Institute, in Chicago. Since 1990, Krier has been industrial designer for Giorgetti[3] & Valli e Valli - Assa Abloy,[4] an Italian furniture company.[5]

From the late 1970s onwards Krier has been one of the most influential neo-traditional architects and planners. He is best known for his ongoing development of Poundbury, an urban extension to Dorchester, UK for the Duchy of Cornwall under the guidance of the Prince of Wales and his Masterplan for Paseo Cayalá, an extension of Guatemala City. He is one of the first and most prominent critics of architectural modernism, mainly of its functional zoning and the ensuing suburbanism, campaigning for the reconstruction of the traditional European city model and its growth based on the polycentric city model. In 1990, of the nine experts invited he was the only one to support the Dresden citizens initiative to reconstruct the historic Dresden Frauenkirche and the Historische Neumarkt area and, in 2007, the Frankfurt Altstadt Forum,[6] citizen initiative which succeeded in reconstructing the historic "Hühnermarkt" area against strong professional and political opposition.

These ideas had a great influence on the New Urbanism movement, both in the USA and Europe. The most complete compilation of them is published in his book The Architecture of Community.

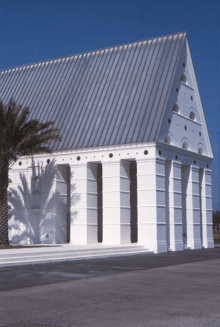

Krier acts as architectural consultant on urban planning projects but only designs buildings of his personal choice. Amongst his best known realizations are the temporary façade at the 1980 Venice Biennale; the Krier house in the resort village of Seaside, Florida, USA (where he also advised on the masterplan); the [[http://www.cm-sintra.pt/en/museums/sao-miguel-odrinhas-archaeological-museum São Miguel Odrinhas Archaeological Museum of Sintra, Portugal; the Windsor Village Hall in Florida; the Jorge M. Perez Architecture Center,[7] the University of Miami School of Architecture in Miami,[8] Florida; and the new Neighbourhood Center Città Nuova in Alessandria, Italy. Léon Krier was involved in the planning for the reconstruction of Tor Bella Monaca, a degraded suburb of Rome.He was working also on the High Malton Masterplan for the Fitzwilliam Estate, Yorkshire, U.K., and on a policy for a long term redevelopment of the whole municipal area of Cattolica, Rimini, Italy, an important Seaside town on the Adriatic Coast which is in a state of decay very untypical for Italy.[9][10] Nowadays, Léon Krier is masterplanning the redevelopment of the demised Fawley Waterside Power Station for landowner Albert Drummond and his group of investors,[11] a masterplan for a new urban center El Socorro, Guatemala City and a new town, Herencia de Allende, San Miguel de Allende.

Though Krier is well known for his defense of classical architecture and the reconstruction of traditional “European city” models, close scrutiny of his work[12] in fact shows a shift from an early Modernist rationalist approach (project for University of Bielefeld, 1968) towards a vernacular and classical approach both formally and technologically. The project that marked a major turning point in his campaigning attitude towards the reconstruction of the traditional European city was his scheme (unrealized) for the 'reconstruction' of his home city of Luxembourg (1978), in response to the modernist redevelopment of the city. He later master planned Luxembourg's new Cite Judiciaire that was to be architecturally designed by his brother (1990-2008)[13]

On architecture and the city

The principle behind Krier’s writings has been to explain the rational foundations of architecture and the city, stating that “In the language of symbols, there can exist no misunderstanding”. That is to say, for Krier, buildings have a rational order and type: a house, a palace, a temple, a campanile, a church; but also a roof, a column, a window, etc., what he terms “nameable objects”. As projects get bigger, he goes on to argue, the buildings should not get bigger, but divide up; thus, for instance, in his unrealized scheme for a school in Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines (1978), France, the school became a “city in miniature”. In searching for such a typological architecture, Krier’s work has been termed “an architecture without a style”. However, it has also been pointed out that the appearance of his architecture is very much like Roman architecture, which he then places in all his projects, be it central London, Stockholm, Tenerife or Florida.”[14]

On the development of the city

Krier has written a number of essays − many first published in the journal Architectural Design, often in his own handwriting in the form of series of didactic annotated diagrams − against modernist town planning and its principle of dividing up the city into a system of single use zones (housing, shopping, industry, leisure, etc.), as well as the resultant suburbia, commuting, etc. Indeed, Krier sees the modern planner as a tyrannical figure that imposes detrimental megastructural scale more dictated by ideology than necessity.[15]

A selection of manifesto texts by Léon Krier

Many of these are available online

- The idea of reconstruction

- Critique of zoning

- Town and country

- Critique of the megastructural city

- Critique of industrialisation

- Urban components

- The city within the city – Les Quartiers

- The size of a city

- Critique of Modernisms

- Organic versus mechanical composition

- Names and nicknames

- Building and architecture

- The reconstruction of the European city

- What is an urban quartier? Form and legislation

The size of the city

Krier agreed with the viewpoint of the late Heinrich Tessenow that there is a strict relationship between the economic and cultural wealth of a city, on the one hand, and the limitation of its population on the other. But this is not a matter of mere hypothesis, he argues, but historical fact. The measurements and geometric organization of a city and of its quarters are not the result of mere chance or accident or simply of economic necessity, but rather represents a civilizing order which is not only aesthetic and technical but also legislative and ethical.

Krier claims, that “the whole of Paris is a pre-industrial city which still works, because it is so adaptable, something the creations of the 20th century will never be. A city like Milton Keynes cannot survive an economic crisis, or any other kind of crisis, because it is planned as a mathematically determined social and economic project. If that model collapses, the city will collapse with it.” Thus Krier argues not merely against the contemporary modernist city (he in fact argues that places like Los Angeles, U.S., are not cities), but against a gigantism tendency in urban growth, evident in the exploding scale of urban networks and buildings in European cities throughout the 19th century which was a result of the concentration of economic, political and cultural power.[16] In response to this, Krier proposed the reconstruction of the European city, based on polycentric settlement models which are dictated not by machine scale but by human scale both horizontally and vertically, of mixed use quarters not exceeding 33 HA (able to be crossed in 10 minutes walk) of building heights of 3-5 floors (able to be walked up comfortably)

Krier has applied his theories in large-scale, detailed plans for cities in the Western world, including: Kingston upon Hull (1977), Rome (1977), Luxembourg (1978), West Berlin (1980–83), Bremen (1980), Stockholm (1981), Poing Nord, Munich (1983), Washington D.C., (1984); Atlantis, Tenerife (1988); Area Fiat, Novoli, Italy, (1993); Knokke-Heist, Heulebrug Belgium (1998); Newquay growth area (2002-2006), Cornwall, UK; Corbeanca Romania (2007); Tor Bella Monaca, Rome, 2010; High Malton Masterplan, Yorkshire, U.K. (2014) and Cattolica, Rimini, Italy (2017). And the ones he is currently implementing for Poundbury Dorset, U.K. (1988 onwards); Paseo Cayalá, Guatemala City (2003 onwards); Fawley Waterside Power Station, Southampton, U.K. (2017 onwards); El Socorro, Guatemala City (2018 onwards) and Herencia de Allende, San Miguel de Allende, México (2018 onwards).

A selection of publications

- Rational Architecture Rationelle, Bruxelles, AAM Editions, 1978.

- Léon Krier. Houses, Palaces, Cities. Edited by Demetri Porphyrios, Architectural Design, 54 7/8, 1984.

- Léon Krier Drawings 1967-1980, Bruxelles, AAM Editions, 1981.

- Albert Speer, Architecture 1932-1942, Bruxelles, AAM Editions, 1985. New York, Monacelli Press, 2013.

- Léon Krier: Architecture & Urban Design 1967-1992, Chicester, John Wiley & Sons, 1993.

- Architecture: Choice or Fate, London, Andreas Papadakis Publishers, 1998.

- Drawings for Architecture, Cambridge (Massachusetts), MIT Press, 2009.

- The Architecture of Community, Washington, Island Press, 2009.

- Léon Krier: selected publications available online .

References

- ↑ "Leon Krier". Driehaus Prize 2003. NDSA. Archived from the original on 6 March 2014. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- ↑ Ian Latham, "Léon Krier. A Profile....", Architectural Design, vol. 57, no 1/2, 1987, p.37

- ↑ "Products". Giorgetti Milano. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

- ↑ "Designers". Valli e Valli. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

- ↑ "Léon Krier Architect and Urban Planner". Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- ↑ "Altstadt Forum Frankfurt". Altstadt Forum Frankfurt. Retrieved 15 July 2018.

- ↑ W. Semes, Steven. "A New Sensibility". Traditional Building Portfolio. Traditional Building and Period Homes. Retrieved 15 July 2018.

- ↑ School of Architecture, Miami University. "The Jorge M. Perez Architecture Center". Retrieved 15 July 2018.

- ↑ Mollura, Domenico (17 May 2017). "Cattolica, il masterplan targato Krier nel nome del decoro urbano". Il giornale dell'Architettura. Retrieved 20 May 2018.

- ↑ comunedicattolica (2017). Presentazione Masterplan - Snaporaz - 7 Aprile.

- ↑ Hellen, Nicholas (26 March 2017). "First smart town to end grind of daily commute". The Sunday Times. Retrieved 20 May 2018.

- ↑ "InternationalArchitect". umemagazine. Retrieved 1 July 2018.

- ↑ "Cité Judiciaire à Luxembourg 1995". robkrier.de. Rob Krier. Retrieved 1 July 2018.

- ↑ Charles Jencks, “Post-Modernism and Eclectic Continuity”, Architectural Design, vol. 57, no 1/2, 1987, 25

- ↑ Leon Krier; 'Houses, Palaces, Cities', Architectural Design, London, 54, 7/8, 1984.

- ↑ Leon Krier, “Urban Components”, Architectural Design, vol. 54, no 7/8, 1984, p.43

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Léon Krier. |

- 2001 interview on New Urbanism

- Introductory Video on YouTube on the Driehaus Prize, feat. Léon Krier

- Article 'Cities for Living' by Roger Scruton at city-journal.org