Language localisation

| Part of a series on |

| Translation |

|---|

|

| Types |

| Theory |

| Technologies |

| Localization |

| Institutional |

|

| Related topics |

|

Language localisation (or localization, see spelling-differences) is the process of adapting a product that has been previously translated into multiple languages to a specific country or region (from Latin locus (place) and the English term locale, "a place where something happens or is set").[1] It is the second phase of a larger process of product translation and cultural adaptation (for specific countries, regions or groups) to account for differences in distinct markets, a process known as internationalisation and localisation.

Language localisation differs from translation activity because it involves a comprehensive study of the target culture in order to correctly adapt the product to local needs. Localisation can be referred to by the numeronym L10N (as in: "L", followed by ten more letters, and then "N").

The localisation process is most generally related to the cultural adaptation and translation of software, video games and websites, as well as audio/voiceover, video or other multimedia content, and less frequently to any written translation (which may also involve cultural adaptation processes). Localisation can be done for regions or countries where people speak different languages or where the same language is spoken: for instance, different dialects of Spanish, with different idioms, are spoken in Spain and in Latin American countries.

The overall process: internationalisation, globalisation and localisation

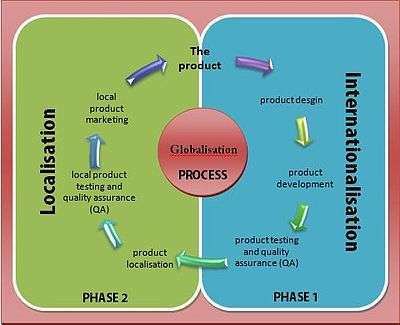

The former Localization Industry Standards Association (LISA) said that globalisation "can best be thought of as a cycle rather than a single process".[2] To globalise is to plan the design and development methods for a product in advance, keeping in mind a multicultural audience, in order to avoid increased costs and quality problems, save time, and smooth the localising effort for each region or country. Localisation is an integral part of the overall process called globalisation.

(based on a chart from the LISA website.)[2]

There are two primary technical processes that comprise globalisation: internationalisation and localisation.

The first phase, internationalisation, encompasses the planning and preparation stages for a product that is built by design to support global markets. This process removes all cultural assumptions, and any country- or language-specific content is stored so that it can be easily adapted. If this content is not separated during this phase, it must be fixed during localisation, adding time and expense to the project. In extreme cases, products that were not internationalised may not be localisable.

The second phase, localisation, refers to the actual adaptation of the product for a specific market. The localisation phase involves, among other things, the four issues LISA describes as linguistic, physical, business and cultural, and technical issues.

At the end of each phase, testing (including quality assurance) is performed to ensure that the product works properly and meets the client's quality expectations.

Translation versus localisation

Though it is sometimes difficult to draw the limits between translation and localisation, in general localisation addresses significant, non-textual components of products or services. In addition to translation (and, therefore, grammar and spelling issues that vary from place to place where the same language is spoken), the localisation process might include adapting graphics; adopting local currencies; using proper format for date and time, addresses, and phone numbers applicable to the location; the choices of colours; cultural references; and many other details, including rethinking the physical structure of a product. All these changes aim to recognise local sensitivities, avoid conflict with local culture, customs, common habits, and enter the local market by merging into its needs and desires.[3] For example, localisation aims to offer country-specific websites of the same company or different editions of a book depending on where it is published. It must be kept in mind that a political entity such as a country is not the same as a language or culture; even in countries where there exists a substantially identical relationship between a language and a political entity, there are almost certainly multiple cultures and multiple minority languages even if the minority languages are spoken by transient populations. For instance, Japan's national language is Japanese and is the primary language for over 99% of the population, but the country recognises 11 languages officially, others are spoken by transient populations, and others are spoken as second or other languages.

Globalisation versus localisation

Whereas localisation is the process of adapting one product to a particular locale, globalisation designs the product to minimise the extra work required for each localisation.

Suppose that a company operating exclusively in the United States chooses to open a major office in China and needs a Chinese-language website. The company offers the same products and services in both countries with only some minor differences, but perhaps some of the elements that appeared in the original website targeted at the United States are offensive or upsetting in China (use of flags, colours, nationalistic images, songs, etc.). Thus, that company might lose a potential market because of small details of presentation.

Furthermore, this company might need to adapt the product to its new buyers; video games are the best example.[4][5]

Now, suppose instead that this company has major offices in a dozen countries and needs a specifically designed website in each of these countries. Before deciding how to localise the website and the products offered in any given country, a professional in the area might advise the company to create an overall strategy: to globalise the way the organisation does business. The company might want to design a framework to codify and support this global strategy. The globalisation strategy and the globalisation framework would provide uniform guidance for the twelve separate localisation efforts.

Globalisation is especially important in mitigating extra work involved in the long-term cycle of localisation. Because localisation is a cycle and not a one-time project, there will always be new texts, updates, and projects to localise. For example, as the original website is updated over time, each of the localised websites already translated will also need to be updated. This cycle of work is continuous as long as the original project continues to evolve. It is therefore important for globalisation processes to be created and streamlined in order to implement ongoing changes.

Translation memory (TM) technology that exists in various translation software platforms can aid in this specific aspect of the globalisation process.[6]

Language tags and codes

Language codes are closely related to the localising process because they indicate the locales involved in the translation and adaptation of the product. They are used in various contexts; for example, they might be informally used in a document published by the European Union[7] or they might be introduced in HTML element under the lang attribute. In the case of the European Union style guide, the language codes are based on the ISO 639-1 alpha-2 code; in HTML, the language tags are generally defined within the Internet Engineering Task Force's Best Current Practice (BCP) 47.[nb 1] The decision to use one type of code or tag versus another depends upon the nature of the project and any requirements set out for the localisation specialist.

Most frequently, there is a primary sub-code that identifies the language (e.g., "en"), and an optional sub-code in capital letters that specifies the national variety (e.g., "GB" or "US" according to ISO 3166-2). The sub-codes are typically linked with a hyphen, though in some contexts it's necessary to substitute this with an underscore.[8]

There are multiple language tag systems available for language codification. For example, the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) specifies both two- and three-letter codes to represent languages in standards ISO 639-1 and ISO 639-2, respectively.

| Language family | Language tag | Language variant |

|---|---|---|

| Bangla | bn-BD | Bangla (Bangladesh) |

| bn-IN | Bangla (India) | |

| Chinese | zh-CN | Mainland China, simplified characters |

| zh-TW | Taiwan, traditional characters | |

| zh-HK | Hong Kong, traditional characters | |

| Dutch | nl-BE | Belgian Dutch |

| nl-NL | Standard Dutch (as spoken in The Netherlands) | |

| English | en-GB | British English |

| en-US | American English | |

| en-CA | Canadian English | |

| en-IN | Indian English | |

| en-AU | Australian English | |

| French | fr-BE | Belgian French |

| fr-CH | "Swiss" French | |

| fr-FR | Standard French (especially in France) | |

| fr-CA | Canadian French | |

| German | de-AT | Austrian German |

| de-DE | Standard German (as spoken in Germany) | |

| de-CH | "Swiss" German | |

| Italian | it-CH | "Swiss" Italian |

| it-IT | Standard Italian (as spoken in Italy) | |

| Portuguese | pt-PT | European Portuguese (as written and spoken in Portugal) |

| pt-BR | Brazilian Portuguese | |

| Spanish | es-ES | Castilian Spanish (as spoken in Central-Northern Spain) |

| es-MX | Mexican Spanish | |

| es-AR | Argentine Spanish | |

| es-CO | Colombian Spanish | |

| es-CL | Chilean Spanish | |

| es-US | American Spanish | |

| Tamil | ta-IN | Indian Tamil |

| ta-LK | Sri Lankan Tamil |

Notes

- ↑ BCP is a persistent name for a series of IETF Request for Comments (RFCs) whose numbers change as they are updated. As of 2015-05-28, the latest included RFC about the principles of language tags is RFC 5646, Tags for the Identification of Languages.

See also

References

- ↑ "locale". The New Oxford American Dictionary (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. 2005.

- 1 2 "What is Globalization?". LISA. Romainmôtier, Switzerland: Localization Industry Standards Association. Archived from the original on January 1, 2011. Retrieved 6 September 2010.

- ↑ Pagano, Annie (June 2018). "The Importance Of Website Localization In A Global Marketplace". Interpreter and Translators, Inc. Glastonbury,Connecticut: Interpreters and Translators, Inc.

- ↑ Chandler, Heather Maxwell (October–November 2008). "Practical skills for video game translators". MultiLingual. Sandpoint, Idaho: MultiLingual Computing.

- ↑ Crosignani, Simone; Ballista, Andrea; Minazzi, Fabio (October–November 2008). "Preserving the spell in games localization". MultiLingual. Sandpoint, Idaho: MultiLingual Computing.

- ↑ "Best Way to Translate a Website for Accuracy & SEO". Pairaphrase. Pairaphrase Blog. Retrieved 4 January 2018.

- ↑ "7.2.1. Order of language versions and ISO codes (multilingual texts)". Interinstitutional style guide. Europa Publications Office. 1 July 2010.

- ↑ drepper (18 February 2007). "libc/localedata/SUPPORTED - view - 1.102". sources.redhat.com. Red Hat. Retrieved 6 September 2010. (List of supported locales in the GNU libc library.)

thailand

External links

- Association of Language Companies (USA)

- Globalization and Localization Association (GALA)

- Localization World Conference

- Localisation Research Centre

- Localisation Company SLSP

- Guide to Localization.pdf|Starting Guide to Localization

- Introduction: Localization guidelines

- Mozilla Localization Project

- Foreignword - List of translation magazines

- W3C: Internationalization - Language tags in HTML and XML

- Library of Congress List of ISO 639-2 (alpha 3) Language Codes