Lamarckism

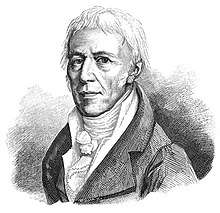

Lamarckism (or Lamarckian inheritance) is the hypothesis that an organism can pass on characteristics that it has acquired through use or disuse during its lifetime to its offspring. It is also known as the inheritance of acquired characteristics or soft inheritance. It is inaccurately[1][2] named after the French biologist Jean-Baptiste Lamarck (1744–1829), who incorporated the action of soft inheritance into his evolutionary theories as a supplement to his concept of orthogenesis, a drive towards complexity. The theory is cited in textbooks to contrast with Darwinism. This paints a false picture of the history of biology, as Lamarck did not originate the idea of soft inheritance, which was known from the classical era onwards. It was not the primary focus of Lamarck's theory of evolution; further, in On the Origin of Species (1859), Charles Darwin supported the idea of "use and disuse inheritance", though rejecting other aspects of Lamarck's theory.

Many researchers from the 1860s onwards attempted to find evidence for the theory, but these have all been explained away either by other mechanisms such as genetic contamination, or as fraud. Later, Mendelian genetics supplanted the notion of inheritance of acquired traits, eventually leading to the development of the modern synthesis, and the general abandonment of the Lamarckism in biology. Despite this, interest in Lamarckism has continued.

Studies in the field of epigenetics and somatic hypermutation[3][4] have highlighted the possible inheritance of behavioral traits acquired by the previous generation.[5][6][7][8][9] These remain controversial, not least because historians of science have asserted that it is inaccurate to describe transgenerational epigenetic inheritance as a form of Lamarckism.[10][11][12][13] The inheritance of the hologenome, consisting of the genomes of all an organism's symbiotic microbes as well as its own genome, is also somewhat Lamarckian in effect, though entirely Darwinian in its mechanisms.

Early history

Origins

The inheritance of acquired characteristics was proposed in ancient times, and remained a current idea for many centuries. The historian of science Conway Zirkle wrote that:[14]

Lamarck was neither the first nor the most distinguished biologist to believe in the inheritance of acquired characters. He merely endorsed a belief which had been generally accepted for at least 2,200 years before his time and used it to explain how evolution could have taken place. The inheritance of acquired characters had been accepted previously by Hippocrates, Aristotle, Galen, Roger Bacon, Jerome Cardan, Levinus Lemnius, John Ray, Michael Adanson, Jo. Fried. Blumenbach and Erasmus Darwin among others.[14]

Zirkle noted that Hippocrates described pangenesis, whereas Aristotle thought it impossible; but that all the same, Aristotle implicitly agreed to the inheritance of acquired characteristics, giving the example of the inheritance of a scar, or of blindness, though noting that children do not always resemble their parents. Zirkle recorded that Pliny the Elder thought much the same. Zirkle also pointed out that stories involving the idea of inheritance of acquired characteristics appear numerous times in ancient mythology and the Bible, and persisted through to Rudyard Kipling's Just So Stories.[15]

Between 1794 and 1796 Erasmus Darwin wrote Zoonomia suggesting "that all warm-blooded animals have arisen from one living filament... with the power of acquiring new parts" in response to stimuli, with each round of "improvements" being inherited by successive generations.[16]

Darwin's pangenesis

Charles Darwin's On the Origin of Species proposed natural selection as the main mechanism for development of species, but did not rule out a variant of Lamarckism as a supplementary mechanism.[17] Darwin called his Lamarckian theory pangenesis, and explained it in the final chapter of his book The Variation of Animals and Plants under Domestication (1868), after describing numerous examples to demonstrate what he considered to be the inheritance of acquired characteristics. Pangenesis, which he emphasised was a hypothesis, was based on the idea that somatic cells would, in response to environmental stimulation (use and disuse), throw off 'gemmules' or 'pangenes' which travelled around the body, though not necessarily in the bloodstream. These pangenes were microscopic particles that supposedly contained information about the characteristics of their parent cell, and Darwin believed that they eventually accumulated in the germ cells where they could pass on to the next generation the newly acquired characteristics of the parents.[18]

Darwin's half-cousin, Francis Galton, carried out experiments on rabbits, with Darwin's cooperation, in which he transfused the blood of one variety of rabbit into another variety in the expectation that its offspring would show some characteristics of the first. They did not, and Galton declared that he had disproved Darwin's hypothesis of pangenesis, but Darwin objected, in a letter to the scientific journal Nature, that he had done nothing of the sort, since he had never mentioned blood in his writings. He pointed out that he regarded pangenesis as occurring in protozoa and plants, which have no blood.[19]

Lamarck's evolutionary framework

Lamarck proposed a systematic theoretical framework for understanding evolution. He saw evolution as comprising four laws:[20][21]

First law

"Life by its own force, tends to increase the volume of all organs which possess the force of life, and the force of life extends the dimensions of those parts up to a extent that those parts bring to themselves;"

Second law

"The production of a new organ in an animal body, results from a new requirement arising. and which continues to make itself felt, and a new movement which that requirement gives birth to, and its upkeep/maintenance;"

Third Law

"The development of the organs, and their ability, are constantly a result of the use of those organs."

Fourth Law

"All that has been acquired, traced, or changed, in the physiology of individuals, during their life, is conserved through the genesis, reproduction, and transmitted to new individuals who are related to those who have undergone those changes."

Lamarck's discussion of heredity

In an aside from his evolutionary framework, Lamarck briefly mentioned two traditional ideas in his discussion of heredity, in his day considered to be generally true. The first was the idea of use versus disuse; he theorized that individuals lose characteristics they do not require, or use, and develop characteristics that are useful. The second was to argue that the acquired traits were heritable. He gave as an imagined illustration the idea that when giraffes stretch their necks to reach leaves high in trees, they would strengthen and gradually lengthen their necks. These giraffes would then have offspring with slightly longer necks. In the same way, he argued, a blacksmith, through his work, strengthens the muscles in his arms, and thus his sons would have similar muscular development when they mature. In 1830, Lamarck stated the following two laws:[22]

- Première Loi: Dans tout animal qui n' a point dépassé le terme de ses développemens, l' emploi plus fréquent et soutenu d' un organe quelconque, fortifie peu à peu cet organe, le développe, l' agrandit, et lui donne une puissance proportionnée à la durée de cet emploi ; tandis que le défaut constant d' usage de tel organe, l'affoiblit insensiblement, le détériore, diminue progressivement ses facultés, et finit par le faire disparoître.[22]

- Deuxième Loi: Tout ce que la nature a fait acquérir ou perdre aux individus par l' influence des circonstances où leur race se trouve depuis long-temps exposée, et, par conséquent, par l' influence de l' emploi prédominant de tel organe, ou par celle d' un défaut constant d' usage de telle partie ; elle le conserve par la génération aux nouveaux individus qui en proviennent, pourvu que les changemens acquis soient communs aux deux sexes, ou à ceux qui ont produit ces nouveaux individus.[22]

English translation:

- First Law [Use and Disuse]: In every animal which has not passed the limit of its development, a more frequent and continuous use of any organ gradually strengthens, develops and enlarges that organ, and gives it a power proportional to the length of time it has been so used; while the permanent disuse of any organ imperceptibly weakens and deteriorates it, and progressively diminishes its functional capacity, until it finally disappears.

- Second Law [Soft Inheritance]: All the acquisitions or losses wrought by nature on individuals, through the influence of the environment in which their race has long been placed, and hence through the influence of the predominant use or permanent disuse of any organ; all these are preserved by reproduction to the new individuals which arise, provided that the acquired modifications are common to both sexes, or at least to the individuals which produce the young.[23]

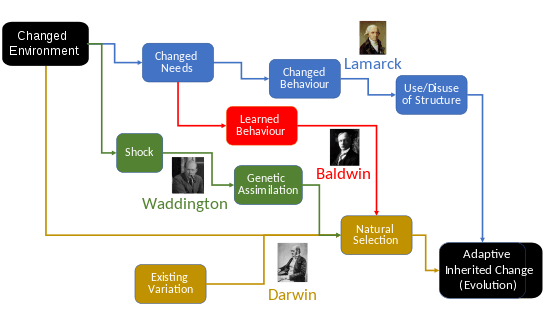

In essence, a change in the environment brings about change in "needs" (besoins), resulting in change in behavior, bringing change in organ usage and development, bringing change in form over time—and thus the gradual transmutation of the species. However, as historians of science such as Ghiselin and Gould have pointed out, these ideas were not original to Lamarck.[1][24]

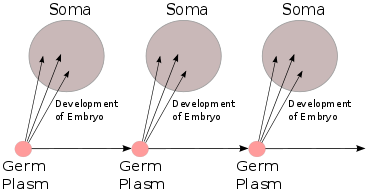

Weismann's experiment

The idea that germline cells contain information that passes to each generation unaffected by experience and independent of the somatic (body) cells, came to be referred to as the Weismann barrier, as it would make Lamarckian inheritance from changes to the body difficult or impossible.[25]

August Weismann conducted the experiment of removing the tails of 68 white mice, and those of their offspring over five generations, and reporting that no mice were born in consequence without a tail or even with a shorter tail. In 1889, he stated that "901 young were produced by five generations of artificially mutilated parents, and yet there was not a single example of a rudimentary tail or of any other abnormality in this organ."[26] The experiment, and the theory behind it, were thought at the time to be a refutation of Lamarckism.[25]

However, the experiment's effectiveness in refuting Lamarck's hypothesis is doubtful, as it did not address the use and disuse of characteristics in response to the environment. The biologist Peter Gauthier noted that:[27]

Can Weismann's experiment be considered a case of disuse? Lamarck proposed that when an organ was not used, it slowly, and very gradually atrophied. In time, over the course of many generations, it would gradually disappear as it was inherited in its modified form in each successive generation. Cutting the tails off mice does not seem to meet the qualifications of disuse, but rather falls in a category of accidental misuse... Lamarck's hypothesis has never been proven experimentally and there is no known mechanism to support the idea that somatic change, however acquired, can in some way induce a change in the germplasm. On the other hand it is difficult to disprove Lamarck's idea experimentally, and it seems that Weismann's experiment fails to provide the evidence to deny the Lamarckian hypothesis, since it lacks a key factor, namely the willful exertion of the animal in overcoming environmental obstacles.[27]

The biologist and historian of science Michael Ghiselin also considered the Weismann tail-chopping experiment to have no bearing on the Lamarckian hypothesis:[1]

The acquired characteristics that figured in Lamarck's thinking were changes that resulted from an individual's own drives and actions, not from the actions of external agents. Lamarck was not concerned with wounds, injuries or mutilations, and nothing that Lamarck had set forth was tested or "disproven" by the Weismann tail-chopping experiment.[1]

Textbook Lamarckism

The identification of Lamarckism with the inheritance of acquired characteristics is regarded by evolutionary biologists including Michael Ghiselin as a falsified artifact of the subsequent history of evolutionary thought, repeated in textbooks without analysis, and wrongly contrasted with a falsified picture of Darwin's thinking. Ghiselin notes that "Darwin accepted the inheritance of acquired characteristics, just as Lamarck did, and Darwin even thought that there was some experimental evidence to support it."[1] American paleontologist and historian of science Stephen Jay Gould wrote that in the late 19th century, evolutionists "re-read Lamarck, cast aside the guts of it ... and elevated one aspect of the mechanics—inheritance of acquired characters—to a central focus it never had for Lamarck himself."[28] He argued that "the restriction of 'Lamarckism' to this relatively small and non-distinctive corner of Lamarck's thought must be labelled as more than a misnomer, and truly a discredit to the memory of a man and his much more comprehensive system."[2][29]

Neo-Lamarckism

Context

The period of the history of evolutionary thought between Darwin's death in the 1880s, and the foundation of population genetics in the 1920s and the beginnings of the modern evolutionary synthesis in the 1930s, is called the eclipse of Darwinism by some historians of science. During that time many scientists and philosophers accepted the reality of evolution but doubted whether natural selection was the main evolutionary mechanism.[30]

Among the most popular alternatives were theories involving the inheritance of characteristics acquired during an organism's lifetime. Scientists who felt that such Lamarckian mechanisms were the key to evolution were called neo-Lamarckians. They included the British botanist George Henslow (1835–1925), who studied the effects of environmental stress on the growth of plants, in the belief that such environmentally-induced variation might explain much of plant evolution, and the American entomologist Alpheus Spring Packard, Jr., who studied blind animals living in caves and wrote a book in 1901 about Lamarck and his work.[31][32] Also included were paleontologists like Edward Drinker Cope and Alpheus Hyatt, who observed that the fossil record showed orderly, almost linear, patterns of development that they felt were better explained by Lamarckian mechanisms than by natural selection. Some people, including Cope and the Darwin critic Samuel Butler, felt that inheritance of acquired characteristics would let organisms shape their own evolution, since organisms that acquired new habits would change the use patterns of their organs, which would kick-start Lamarckian evolution. They considered this philosophically superior to Darwin's mechanism of random variation acted on by selective pressures. Lamarckism also appealed to those, like the philosopher Herbert Spencer and the German anatomist Ernst Haeckel, who saw evolution as an inherently progressive process.[31] The German zoologist Theodor Eimer combined Larmarckism with ideas about orthogenesis.[33]

With the development of the modern synthesis of the theory of evolution, and a lack of evidence for a mechanism for acquiring and passing on new characteristics, or even their heritability, Lamarckism largely fell from favour. Unlike neo-Darwinism, neo-Lamarckism is a loose grouping of largely heterodox theories and mechanisms that emerged after Lamarck's time, rather than a coherent body of theoretical work.

19th century

Neo-Lamarckian versions of evolution were widespread in the late 19th century. The idea that living things could to some degree choose the characteristics that would be inherited allowed them things to be in charge of their own destiny as opposed to the Darwinian view, which made them puppets at the mercy of the environment. Such ideas were more popular than natural selection in the late 19th century as it made it possible for biological evolution to fit into a framework of a divine or naturally willed plan, thus the neo-Lamarckian view of evolution was often advocated by proponents of orthogenesis.[34] According to Peter J. Bowler:

One of the most emotionally compelling arguments used by the neo-Lamarckians of the late nineteenth century was the claim that Darwinism was a mechanistic theory which reduced living things to puppets driven by heredity. The selection theory made life into a game of Russian roulette, where life or death was predetermined by the genes one inherited. The individual could do nothing to mitigate bad heredity. Lamarckism, in contrast, allowed the individual to choose a new habit when faced with an environmental challenge and shape the whole future course of evolution.[35]

Scientists from the 1860s onwards conducted numerous experiments that purported to show Lamarckian inheritance. Some examples are described in the table.

| Scientist | Date | Experiment | Claimed result | Rebuttal |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Charles-Édouard Brown-Séquard | 1869 to 1891 | Cut sciatic nerve and dorsal spinal cord of guinea pigs, causing abnormal nervous condition resembling epilepsy | Epileptic offspring | Not Lamarckism, as no use and disuse in response to environment; results could not be replicated; cause possibly a transmitted disease.[36][37][38][39][40][41] |

| Gaston Bonnier | 1884, 1886 | Transplant plants at different altitudes in Alps, Pyrenees | Acquired adaptations | Not controlled from weeds; likely cause genetic contamination[42] |

| Joseph Thomas Cunningham | 1891, 1893, 1895 | Shine light on underside of flatfish | Inherited production of pigment | Disputed cause[43][44][45][46][47][48] |

| Max Standfuss | 1892 to 1917 | Raise butterflies at low temperature | Variations in offspring even without low temperature | Richard Goldschmidt agreed; Ernst Mayr "difficult to interpret".[49][50][51][52] |

Early 20th century

A century after Lamarck, scientists and philosophers continued to seek mechanisms and evidence for the inheritance of acquired characteristics. Experiments were sometimes reported as successful, but from the beginning these were either criticised on scientific grounds or shown to be fakes.[53][54][55][56][57] For instance, in 1906, the philosopher Eugenio Rignano argued for a version that he called "centro-epigenesis",[58][59][60][61][62][63] but it was rejected by most scientists.[64] Some of the experimental approaches are described in the table.

| Scientist | Date | Experiment | Claimed result | Rebuttal |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| William Lawrence Tower | 1907 to 1910 | Colorado potato beetles in extreme humidity, temperature | Heritable changes in size, colour | Criticised by William Bateson; Tower claimed all results lost in fire; William E. Castle visited laboratory, found fire suspicious, doubted claim that steam leak had killed all beetles, concluded faked data.[65][66][67][68][69] |

| Gustav Tornier | 1907 to 1918 | Goldfish, embryos of frogs, newts | Abnormalities inherited | Disputed; possibly an osmotic effect[70][71][72][73] |

| Charles Rupert Stockard | 1910 | Repeated alcohol intoxication of pregnant guinea pigs | Inherited malformations | Raymond Pearl unable to reproduce findings in chickens; Darwinian explanation[74][75] |

| Francis Bertody Sumner | 1921 | Reared mice at different temperatures, humidities | Inherited longer bodies, tails, hind feet | Inconsistent results[76][77] |

| Michael F. Guyer, Elizabeth A. Smith | 1918 to 1924 | Injected fowl serum antibodies for rabbit lens-protein into pregnant rabbits | Eye defects inherited for 8 generations | Disputed, results not replicated[78][79] |

| Paul Kammerer | 1920s | Midwife toad | Black foot-pads inherited | Fraud, ink injected; or, results misinterpreted; case celebrated by Arthur Koestler arguing that opposition was political[80][81] |

| William McDougall | 1920s | Rats solving mazes | Offspring learnt mazes quicker (20 vs 165 trials) | Poor experimental controls[82][83][84][85][86][87][88] |

| John William Heslop-Harrison | 1920s | Peppered moths exposed to soot | Inherited mutations caused by soot | Failure to replicate results; implausible mutation rate[89][90] |

| Ivan Pavlov | 1926 | Conditioned reflex in mice to food and bell | Offspring easier to condition | Pavlov retracted claim; results not replicable[91][92] |

| Coleman Griffith, John Detlefson | 1920 to 1925 | Reared rats on rotating table for 3 months | Inherited balance disorder | Results not replicable; likely cause ear infection[93][94][95][96][97][98] |

| Victor Jollos | 1930s | Heat treatment in Drosophila melanogaster | Directed mutagenesis, a form of orthogenesis | Results not replicable[99][100] |

Late 20th century

The British anthropologist Frederic Wood Jones and the South African paleontologist Robert Broom supported a neo-Lamarckian view of human evolution. The German anthropologist Hermann Klaatsch relied on a neo-Lamarckian model of evolution to try and explain the origin of bipedalism. Neo-Lamarckism remained influential in biology until the 1940s when the role of natural selection was reasserted in evolution as part of the modern evolutionary synthesis.[101] Herbert Graham Cannon, a British zoologist, defended Lamarckism in his 1959 book Lamarck and Modern Genetics.[102] In the 1960s, "biochemical Lamarckism" was advocated by the embryologist Paul Wintrebert.[103]

Neo-Lamarckism was dominant in French biology for more than a century. French scientists who supported neo-Lamarckism included Edmond Perrier (1844–1921), Alfred Giard (1846–1908), Gaston Bonnier (1853–1922) and Pierre-Paul Grassé (1895–1985). They followed two traditions, one mechanistic, one vitalistic after Henri Bergson's philosophy of evolution.[104]

In 1987, Ryuichi Matsuda coined the term "pan-environmentalism" for his evolutionary theory which he saw as a fusion of Darwinism with neo-Lamarckism. He held that heterochrony is a main mechanism for evolutionary change and that novelty in evolution can be generated by genetic assimilation.[105][106] His views were criticized by Arthur M. Shapiro for providing no solid evidence for his theory. Shapiro noted that "Matsuda himself accepts too much at face value and is prone to wish-fulfilling interpretation."[106]

Ideological neo-Lamarckism

A form of Lamarckism was revived in the Soviet Union of the 1930s when Trofim Lysenko promoted the ideologically-driven research programme, Lysenkoism; this suited the ideological opposition of Joseph Stalin to genetics. Lysenkoism influenced Soviet agricultural policy which in turn was later blamed for crop failures.[107]

Critique

George Gaylord Simpson in his book Tempo and Mode in Evolution (1944) claimed that experiments in heredity have failed to corroborate any Lamarckian process.[108] Simpson noted that neo-Lamarckism "stresses a factor that Lamarck rejected: inheritance of direct effects of the environment" and neo-Lamarckism is closer to Darwin's pangenesis than Lamarck's views.[109] Simpson wrote, "the inheritance of acquired characters, failed to meet the tests of observation and has been almost universally discarded by biologists."[110]

Botanist Conway Zirkle pointed out that Lamarck did not originate the hypothesis that acquired characters were heritable, therefore it is incorrect to refer to it as Lamarckism:

What Lamarck really did was to accept the hypothesis that acquired characters were heritable, a notion which had been held almost universally for well over two thousand years and which his contemporaries accepted as a matter of course, and to assume that the results of such inheritance were cumulative from generation to generation, thus producing, in time, new species. His individual contribution to biological theory consisted in his application to the problem of the origin of species of the view that acquired characters were inherited and in showing that evolution could be inferred logically from the accepted biological hypotheses. He would doubtless have been greatly astonished to learn that a belief in the inheritance of acquired characters is now labeled "Lamarckian," although he would almost certainly have felt flattered if evolution itself had been so designated.[15]

Peter Medawar wrote regarding Lamarckism, "very few professional biologists believe that anything of the kind occurs—or can occur—but the notion persists for a variety of nonscientific reasons." Medawar stated there is no known mechanism by which an adaptation acquired in an individual's lifetime can be imprinted on the genome and Lamarckian inheritance is not valid unless it excludes the possibility of natural selection but this has not been demonstrated in any experiment.[111]

Martin Gardner wrote in his book Fads and Fallacies in the Name of Science (1957):

A host of experiments have been designed to test Lamarckianism. All that have been verified have proved negative. On the other hand, tens of thousands of experiments— reported in the journals and carefully checked and rechecked by geneticists throughout the world— have established the correctness of the gene-mutation theory beyond all reasonable doubt... In spite of the rapidly increasing evidence for natural selection, Lamarck has never ceased to have loyal followers.... There is indeed a strong emotional appeal in the thought that every little effort an animal puts forth is somehow transmitted to his progeny.[112]

According to Ernst Mayr, any Lamarckian theory involving the inheritance of acquired characters has been refuted as "DNA does not directly participate in the making of the phenotype and that the phenotype, in turn, does not control the composition of the DNA."[113] Peter J. Bowler has written that although many early scientists took Lamarckism seriously, it was discredited by genetics in the early twentieth century.[114]

Apparently Lamarckian mechanisms

Transgenerational epigenetic inheritance

Epigenetic inheritance has been argued by scientists including Eva Jablonka and Marion J. Lamb to be Lamarckian.[115] Epigenetics is based on hereditary elements other than genes that pass into the germ cells. These include methylation patterns in DNA and chromatin marks on histone proteins, both involved in gene regulation. These marks are responsive to environmental stimuli, differentially affect gene expression, and are adaptive, with phenotypic effects that persist for some generations. The mechanism may also enable the inheritance of behavioral traits, for example in chickens[116][117][118] rats,[119][120] and human populations that have experienced starvation, DNA methylation resulting in altered gene function in both the starved population and their offspring.[121] Methylation similarly mediates epigenetic inheritance in plants such as rice.[122][123] Small RNA molecules, too, may mediate inherited resistance to infection.[124][125][126] Handel and Romagopalan commented that "epigenetics allows the peaceful co-existence of Darwinian and Lamarckian evolution."[127]

Joseph Springer and Dennis Holley commented in 2013 that:[128]

Lamarck and his ideas were ridiculed and discredited. In a strange twist of fate, Lamarck may have the last laugh. Epigenetics, an emerging field of genetics, has shown that Lamarck may have been at least partially correct all along. It seems that reversible and heritable changes can occur without a change in DNA sequence (genotype) and that such changes may be induced spontaneously or in response to environmental factors—Lamarck's "acquired traits." Determining which observed phenotypes are genetically inherited and which are environmentally induced remains an important and ongoing part of the study of genetics, developmental biology, and medicine.[128]

The prokaryotic CRISPR system and Piwi-interacting RNA could be classified as Lamarckian, within a Darwinian framework.[129]

However, the significance of epigenetics in evolution is uncertain. Critics such as Jerry Coyne point out that epigenetic inheritance lasts for only a few generations, so is not a stable basis for evolutionary change.[130][131][132][133]

The evolutionary biologist T. Ryan Gregory contends that epigenetic inheritance should not be considered Lamarckian. According to Gregory, Lamarck did not claim the environment imposed direct effects on organisms. Instead, Lamarck "argued that the environment created needs to which organisms responded by using some features more and others less, that this resulted in those features being accentuated or attenuated, and that this difference was then inherited by offspring." Gregory has stated that Lamarckian evolution in the context of epigenetics is actually closer to Darwin's view rather than Lamarck's.[10]

In 2007, David Haig wrote that research into epigenetic processes does allow a Lamarckian element in evolution but the processes do not challenge the main tenets of the modern evolutionary synthesis as modern Lamarckians have claimed. Haig argued for the primacy of DNA and evolution of epigenetic switches by natural selection.[134] Haig has written that there is a "visceral attraction" to Lamarckian evolution from the public and some scientists, as it posits the world with a meaning, in which organisms can shape their own evolutionary destiny.[135]

Thomas Dickens and Qazi Rahman (2012) have argued that epigenetic mechanisms such as DNA methylation and histone modification are genetically inherited under the control of natural selection and do not challenge the modern synthesis. They dispute the claims of Jablonka and Lamb on Lamarckian epigenetic processes.[136]

In 2015, Khursheed Iqbal and colleagues discovered that although "endocrine disruptors exert direct epigenetic effects in the exposed fetal germ cells, these are corrected by reprogramming events in the next generation."[138] Adam Weiss argued that bringing back Lamarck in the context of epigenetics is misleading, commenting, "We should remember [Lamarck] for the good he contributed to science, not for things that resemble his theory only superficially. Indeed, thinking of CRISPR and other phenomena as Lamarckian only obscures the simple and elegant way evolution really works."[139]

Somatic hypermutation and reverse transcription to germline

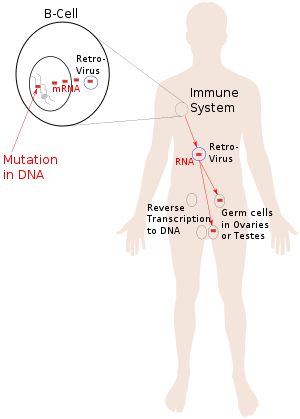

In the 1970s, the Australian immunologist Edward J. Steele developed a neo-Lamarckian theory of somatic hypermutation within the immune system, and coupled it to the reverse transcription of RNA derived from body cells to the DNA of germline cells. This reverse transcription process supposedly enabled characteristics or bodily changes acquired during a lifetime to be written back into the DNA and passed on to subsequent generations.[140][141]

The mechanism was meant to explain why homologous DNA sequences from the VDJ gene regions of parent mice were found in their germ cells and seemed to persist in the offspring for a few generations. The mechanism involved the somatic selection and clonal amplification of newly acquired antibody gene sequences generated via somatic hypermutation in B-cells. The messenger RNA products of these somatically novel genes were captured by retroviruses endogenous to the B-cells, and were then transported through the bloodstream where they could breach the Weismann or soma-germ barrier and reverse transcribe the newly acquired genes into the cells of the germ line, in the manner of Darwin's pangenes.[4][3][142]

The historian of biology Peter J. Bowler noted in 1989 that other scientists had been unable to reproduce his results, and described the scientific consensus at the time:[137]

There is no feedback of information from the proteins to the DNA, and hence no route by which characteristics acquired in the body can be passed on through the genes. The work of Ted Steele (1979) provoked a flurry of interest in the possibility that there might, after all, be ways in which this reverse flow of information could take place. ... [His] mechanism did not, in fact, violate the principles of molecular biology, but most biologists were suspicious of Steele's claims, and attempts to reproduce his results have failed.[137]

Bowler commented that "[Steele's] work was bitterly criticized at the time by biologists who doubted his experimental results and rejected his hypothetical mechanism as implausible."[137]

Hologenome theory of evolution

The hologenome theory of evolution, while Darwinian, has Lamarckian aspects. An individual animal or plant lives in symbiosis with many microorganisms, and together they have a "hologenome" consisting of all their genomes. The hologenome can vary like any other genome by mutation, sexual recombination, and chromosome rearrangement, but in addition it can vary when populations of microorganisms increase or decrease (resembling Lamarckian use and disuse), and when it gains new kinds of microorganism (resembling Lamarckian inheritance of acquired characteristics). These changes are then passed on to offspring.[144] The mechanism is largely uncontroversial, and natural selection does sometimes occur at whole system (hologenome) level, but it is not clear that this is always the case.[143]

Baldwin effect

The Baldwin effect, named after the psychologist James Mark Baldwin by George Gaylord Simpson in 1953, proposes that the ability to learn new behaviours can improve an animal's reproductive success, and hence the course of natural selection on its genetic makeup. Simpson stated that the mechanism was "not inconsistent with the modern synthesis" of evolutionary theory,[145] though he doubted that it occurred very often, or could be proven to occur. He noted that the Baldwin effect provide a reconciliation between the neo-Darwinian and neo-Lamarckian approaches, something that the modern synthesis had seemed to render unnecessary. In particular, the effect allows animals to adapt to a new stress in the environment through behavioural changes, followed by genetic change. This somewhat resembles Lamarckism but without requiring animals to inherit characteristics acquired by their parents.[146] The Baldwin effect is broadly accepted by Darwinists.[147]

In sociocultural evolution

Within the history of technology, Lamarckism has been used in linking cultural development to human evolution by classifying artefacts as extensions of human anatomy: in other words, as the acquired cultural characteristics of human beings. Ben Cullen has shown that a strong element of Lamarckism exists in sociocultural evolution.[148]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Ghiselin, Michael T. (1994). "The Imaginary Lamarck: A Look at Bogus "History" in Schoolbooks". The Textbook Letter. The Textbook League (September–October 1994).

- 1 2 Gould 2002, pp. 177–178

- 1 2 Steele, E.J. (2016). "Somatic hypermutation in immunity and cancer: Critical analysis of strand-biased and codon-context mutation signatures". DNA Repair. 45 (2016): 1–2 4. doi:10.1016/j.dnarep.2016.07.001. PMID 27449479.

- 1 2 Steele, E. J. (1981). Somatic selection and adaptive evolution : on the inheritance of acquired characters (2nd ed.). University of Chicago Press.

- ↑ Roth, Tania L.; Lubin, Farah D.; Funk, Adam J.; et al. (May 1, 2009). "Lasting Epigenetic Influence of Early-Life Adversity on the BDNF Gene". Biological Psychiatry. 65 (9): 760–769. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.11.028. PMC 3056389. PMID 19150054.

- ↑ Arai, Junko A.; Shaomin Li; Hartley, Dean M.; et al. (February 4, 2009). "Transgenerational Rescue of a Genetic Defect in Long-Term Potentiation and Memory Formation by Juvenile Enrichment". The Journal of Neuroscience. Society for Neuroscience. 29 (5): 1496–1502. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5057-08.2009. PMC 3408235. PMID 19193896.

- ↑ Hackett, Jamie A.; Sengupta, Roopsha; Zylicz, Jan J.; et al. (January 25, 2013). "Germline DNA Demethylation Dynamics and Imprint Erasure Through 5-Hydroxymethylcytosine". Science. American Association for the Advancement of Science. 339 (6118): 448–452. Bibcode:2013Sci...339..448H. doi:10.1126/science.1229277. PMC 3847602. PMID 23223451.

- ↑ Bonduriansky, Russell (June 2012). "Rethinking heredity, again". Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 27 (6): 330–336. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2012.02.003. PMID 22445060.

- ↑ Skinner, Michael K. (May 2015). "Environmental Epigenetics and a Unified Theory of the Molecular Aspects of Evolution: A Neo-Lamarckian Concept that Facilitates Neo-Darwinian Evolution". Genome Biology and Evolution. 7 (5): 1296–1302. doi:10.1093/gbe/evv073. PMC 4453068. PMID 25917417.

- 1 2 Gregory, T. Ryan (March 8, 2009). "Lamarck didn't say it, Darwin did". Genomicron (Blog). Retrieved 2015-11-04.

- ↑ Wilkins 2009, pp. 295–315

- ↑ Burkhardt, Richard W., Jr. (August 2013). "Lamarck, Evolution, and the Inheritance of Acquired Characters". Genetics. Genetics Society of America. 194 (4): 793–805. doi:10.1534/genetics.113.151852. PMC 3730912. PMID 23908372.

- ↑ Penny, David (June 2015). "Epigenetics, Darwin, and Lamarck". Genome Biology and Evolution. 7 (6): 1758–1760. doi:10.1093/gbe/evv107. PMC 4494054. PMID 26026157.

- 1 2 Zirkle, Conway (1935). "The Inheritance of Acquired Characters and the Provisional Hypothesis of Pangenesis". The American Naturalist. 69: 417–445. doi:10.1086/280617.

- 1 2 Zirkle, Conway (January 1946). "The Early History of the Idea of the Inheritance of Acquired Characters and of Pangenesis". Transactions of the American Philosophical Society. 35 (2): 91–151. doi:10.2307/1005592. JSTOR 1005592.

- ↑ Darwin 1794–1796, Vol I, section XXXIX

- ↑ Desmond & Moore 1991, p. 617: "But Darwin was loath to let go of the notion that a well-used and strengthened organ could be inherited."

- ↑ Darwin, Charles (April 27, 1871). "Pangenesis". Nature. 3 (78): 502–503. Bibcode:1871Natur...3..502D. doi:10.1038/003502a0.

- ↑ Liu, Yongsheng (2008). "A new perspective on Darwin's Pangenesis". Biological Reviews. 83 (2): 141–149. doi:10.1111/j.1469-185x.2008.00036.x.

- ↑ Larson, Edward J. (2004). A Growing sense of progress. Evolution: The remarkable history of a Scientific Theory. Modern Library. pp. 38–41.

- ↑ Gould, Stephen (2001). The lying stones of Marrakech : penultimate reflections in natural history. Vintage. pp. 119–121. ISBN 978-0-09-928583-0.

- 1 2 3 Lamarck 1830, p. 235

- ↑ Lamarck 1914, p. 113

- ↑ Gould 2002

- 1 2 Romanes, George John (1893). An examination of Weismannism. Open Court.

- ↑ Weismann 1889, "The Supposed Transmission of Mutilations" (1888), p. 432

- 1 2 Gauthier, Peter (March–May 1990). "Does Weismann's Experiment Constitute a Refutation of the Lamarckian Hypothesis?". BIOS. 61 (1/2): 6–8. JSTOR 4608123.

- ↑ Gould 1980, p. 66

- ↑ Gould, Stephen Jay (October 4, 1979). "Another Look at Lamarck". New Scientist. Vol. 84 no. 1175. pp. 38–40. Retrieved 2015-11-09.

- ↑ Quammen 2006, p. 216

- 1 2 Bowler 2003, pp. 236–244

- ↑ Quammen 2006, pp. 218, 220

- ↑ Quammen 2006, p. 221

- ↑ Bowler 1992

- ↑ Bowler 2003, p. 367

- ↑ Mumford 1921, p. 209

- ↑ Mason 1956, p. 343

- ↑ Burkhardt 1995, p. 166

- ↑ Raitiere 2012, p. 299

- ↑ Linville & Kelly 1906, p. 108

- ↑ Aminoff 2011, p. 192

- ↑ Kohler 2002, p. 167

- ↑ Cunningham, Joseph Thomas (1891). "An Experiment concerning the Absence of Color from the lower Sides of Flat-fishes". Zoologischer Anzeiger. 14: 27–32.

- ↑ Cunningham, Joseph Thomas (May 1893). "Researches on the Coloration of the Skins of Flat Fishes". Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom. 3 (1): 111–118. doi:10.1017/S0025315400049596.

- ↑ Cunningham, Joseph Thomas (May 1895). "Additional Evidence on the Influence of Light in producing Pigments on the Lower Sides of Flat Fishes". Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom. 4: 53–59. doi:10.1017/S0025315400050761.

- ↑ Moore, Eldon (September 15, 1928). "The New View of Mendelism". The Spectator (Book review). Vol. 141 no. 5229. p. 337. Retrieved 2015-10-24. Review of Modern Biology (1928) by J. T. Cunningham.

- ↑ Cock & Forsdyke 2008, pp. 132–133

- ↑ Morgan 1903, pp. 257–259

- ↑ Goldschmidt 1940, pp. 266–267

- ↑ Burkhardt 1998, "Lamarckism in Britain and the United States", p. 348

- ↑ Forel 1934, p. 36

- ↑ Packard, A. S. (July 10, 1896). "Handbuch der paläarktischen Gross-Schmetterlinge für Forscher und Sammler. Zweite gänzlich umgearbeitete und durch Studien zur Descendenztheorie erweitete Auflage, etc". Science (Book review). 4 (80): 52–54. doi:10.1126/science.4.80.52-c. Review of Handbuch der paläarktischen Gross-Schmetterlinge für Forscher und Sammler (1896) by Maximilian Rudolph Standfuss.

- ↑ Delage & Goldsmith 1912, p. 210

- ↑ Kohler 2002, pp. 202–204

- ↑ Mitman 1992, p. 219

- ↑ Bowler 2003, pp. 245–246

- ↑ Medawar 1985, p. 168

- ↑ Rignano 1906

- ↑ Rignano & Harvey 1911

- ↑ Eastwood, M. Lightfoot (October 1912). "Reviewed Work: Eugenio Rignano Upon the Inheritance of Acquired Characters by C.H. Harvey". International Journal of Ethics. 23 (1): 117–118. doi:10.1086/206715. JSTOR 2377122.

- ↑ Newman 1921, p. 335

- ↑ Rignano 1926

- ↑ Carmichael, Leonard (December 23, 1926). "Reviewed Work: Biological Memory by Eugenio Rignano, E. W. MacBride". The Journal of Philosophy. 23 (26): 718–720. doi:10.2307/2014451. JSTOR 2014451.

- ↑ "(1) Upon the Inheritance of Acquired Characters (2) Biological Aspects of Human Problems". Nature (Book review). 89 (2232): 576–578. August 8, 1912. Bibcode:1912Natur..89..576.. doi:10.1038/089576a0.

- ↑ Bateson, William (July 3, 1919). "Dr. Kammerer's Testimony to the Inheritance of Acquired Characters". Nature (Letter to editor). 103 (2592): 344–345. Bibcode:1919Natur.103..344B. doi:10.1038/103344b0.

- ↑ Bateson 1913, pp. 219–227

- ↑ Weinstein 1998, "A Note on W. L. Tower's Lepinotarsa Work," pp. 352–353

- ↑ Kohler 2002, pp. 202–204

- ↑ Mitman 1992, p. 219

- ↑ MacBride, Ernest (January 1924). "The work of tornier as affording a possible explanation of the causes of mutations". The Eugenics Review. 15 (4): 545–555. PMC 2942563. PMID 21259774.

- ↑ Cunningham 1928, pp. 84–97

- ↑ Sladden, Dorothy E. (May 1930). "Experimental Distortion of Development in Amphibian Tadpoles". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 106 (744): 318–325. doi:10.1098/rspb.1930.0031.

- ↑ Sladden, Dorothy E. (November 1932). "Experimental Distortion of Development in Amphibian Tadpoles. Part II". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 112 (774): 1–12. doi:10.1098/rspb.1932.0072.

- ↑ Blumberg 2010, pp. 69–70

- ↑ Delage & Goldsmith 1912, p. 210

- ↑ Young 1922, p. 249

- ↑ Child 1945, pp. 146–173

- ↑ Guyer, Michael F.; Smith, E. A. (March 1920). "Transmission of Eye-Defects Induced in Rabbits by Means of Lens-Sensitized Fowl-Serum". PNAS. 6 (3): 134–136. Bibcode:1920PNAS....6..134G. doi:10.1073/pnas.6.3.134. PMC 1084447. PMID 16576477.

- ↑ Medawar 1985, p. 169

- ↑ Bowler 2003, pp. 245–246

- ↑ Moore 2002, p. 330

- ↑ McDougall, William (April 1938). "Fourth Report on a Lamarckian Experiment". General Section. British Journal of Psychology. 28 (4): 365–395. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8295.1938.tb00882.x.

- ↑ Pantin, Carl F. A. (November 1957). "Oscar Werner Tiegs. 1897-1956". Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society. 3: 247–255. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1957.0017.

- ↑ Agar, Wilfred E.; Drummond, Frank H.; Tiegs, Oscar W. (July 1935). "A First Report on a Test of McDougall'S Lamarckian Experiment on the Training of Rats". The Journal of Experimental Biology. 12 (3): 191–211.

- ↑ Agar, Wilfred E.; Drummond, Frank H.; Tiegs, Oscar W. (October 1942). "Second Report on a Test of McDougall's Lamarckian Experiment on the Training of Rats". The Journal of Experimental Biology. 19 (2): 158–167.

- ↑ Agar, Wilfred E.; Drummond, Frank H.; Tiegs, Oscar W. (June 1948). "Third Report on a Test of McDougall'S Lamarckian Experiment on the Training of Rats". The Journal of Experimental Biology. 25 (2): 103–122. Retrieved 2015-10-28.

- ↑ Agar, Wilfred E.; Drummond, Frank H.; Tiegs, Oscar W.; Gunson, Mary M. (September 1954). "Fourth (Final) Report on a Test of McDougall'S Lamarckian Experiment on the Training of Rats". The Journal of Experimental Biology. 31 (3): 308–321.

- ↑ Medawar 1985, p. 168

- ↑ Hagen 2002, p. 144: "During the 1920s, the entomologist J. W. Heslop-Harrison published experimental data supporting his claim that chemicals in soot caused widespread mutations from light winged to the dark winged form. Because these mutations were supposedly passed on to subsequent generations, Harrison claimed that he had documented a case of inheritance of acquired traits. Other biologists failed to replicate Harrison's results, and R. A. Fisher pointed out that Harrison's hypothesis required a mutation rate far higher than any previously reported."

- ↑ Moore & Decker 2008, p. 203

- ↑ McDougall 1934, p. 180

- ↑ Macdowell, E. Carleton; Vicari, Emilia M. (May 1921). "Alcoholism and the behavior of white rats. I. The influence of alcoholic grandparents upon maze-behavior". Journal of Experimental Zoology. 33 (1): 208–291. doi:10.1002/jez.1400330107.

- ↑ Griffith, Coleman R. (November–December 1920). "The Effect upon the White Rat of Continued Bodily Rotation". The American Naturalist. 54 (635): 524–534. doi:10.1086/279783. JSTOR 2456346.

- ↑ Griffith, Coleman R. (December 15, 1922). "Are Permanent Disturbances of Equilibration Inherited?". Science. 56 (1459): 676–678. Bibcode:1922Sci....56..676G. doi:10.1126/science.56.1459.676. PMID 17778266.

- ↑ Detlefsen, John A. (1923). "Are the Effects of Long-Continued Rotation in Rats Inherited?". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. 62 (5): 292–300. JSTOR 984462.

- ↑ Detlefsen, John A. (April 1925). "The inheritance of acquired characters". Physiological Reviews. 5 (2): 224–278.

- ↑ Dorcus, Roy M. (June 1933). "The effect of intermittent rotation on orientation and the habituation of nystagmus in the rat, and some observations on the effects of pre-natal rotation on post-natal development". Journal of Comparative Psychology. 15 (3): 469–475. doi:10.1037/h0074715.

- ↑ Otho S. A. Sprague Memorial Institute 1940, p. 162

- ↑ Jollos, Victor (September 1934). "Inherited changes produced by heat-treatment in Drosophila melanogaster". Genetica. 16 (5–6): 476–494. doi:10.1007/BF01984742.

- ↑ Harwood 1993, pp. 121–131

- ↑ Wood 2013

- ↑ Cannon 1975

- ↑ Boesiger 1974, p. 29

- ↑ Loison, Laurent (November 2011). "French Roots of French Neo-Lamarckisms, 1879–1985". Journal of the History of Biology. 44 (4): 713–744. doi:10.1007/s10739-010-9240-x. PMID 20665089.

- ↑ Pearson, Roy Douglas (March 1988). "Reviews". Acta Biotheoretica (Book review). 37 (1): 31–36. doi:10.1007/BF00050806. Book reviews of Animal Evolution in Changing Environments: With Special Reference to Abnormal Metamorphosis (1987) by Ryuichi Matsuda and The Evolution of Individuality (1987) by Leo W. Buss.

- 1 2 Shapiro, Arthur M. (1988). "Book Review: Animal Evolution in Changing Environments with Special Reference to Abnormal Metamorphosis" (PDF). Journal of the Lepidopterists' Society (Book review). 42 (2): 146–147. Retrieved 2015-12-11.

- ↑ Baird, Scerri & McIntyre 2006, p. 166

- ↑ Simpson 1944, p. 75

- ↑ Simpson 1964, pp. 14–60

- ↑ Simpson 1965, p. 451

- ↑ Medawar 1985, pp. 166–169

- ↑ Gardner 1957, pp. 142–143

- ↑ Mayr 1997, p. 222: "...the recognition that DNA does not directly participate in the making of the phenotype and that the phenotype, in turn, does not control the composition of the DNA represents the ultimate invalidation of all theories involving the inheritance of acquired characters. This definitive refutation of Lamarck's theory of evolutionary causation clears the air."

- ↑ Bowler 2013, p. 21

- ↑ Jablonka & Lamb 1995

- ↑ Moore 2015

- ↑ Richards, Eric J. (May 2006). "Inherited epigenetic variation — revisiting soft inheritance". Nature Reviews Genetics. 7 (5): 395–401. doi:10.1038/nrg1834. PMID 16534512.

- ↑ Nätt, Daniel; Lindqvist, Niclas; Stranneheim, Henrik; et al. (July 28, 2009). Pizzari, Tom, ed. "Inheritance of Acquired Behaviour Adaptations and Brain Gene Expression in Chickens". PLOS ONE. Public Library of Science. 4 (7): e6405. Bibcode:2009PLoSO...4.6405N. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0006405. PMC 2713434. PMID 19636381.

- ↑ Sheau-Fang Ng; Lin, Ruby C. Y.; Laybutt, D. Ross; et al. (October 21, 2010). "Chronic high-fat diet in fathers programs β-cell dysfunction in female rat offspring". Nature. 467 (7318): 963–966. Bibcode:2010Natur.467..963N. doi:10.1038/nature09491. PMID 20962845.

- ↑ Gibson, Andrea (June 16, 2013). "Obese male mice father offspring with higher levels of body fat" (Press release). Ohio University. Retrieved 2015-11-02.

- ↑ Lumey, Lambert H.; Stein, Aryeh D.; Ravelli, Anita C. J. (July 1995). "Timing of prenatal starvation in women and birth weight in their first and second born offspring: The Dutch famine birth cohort study". European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology. 61 (1): 23–30. doi:10.1016/0028-2243(95)02149-M. INIST:3596539.

- ↑ Akimoto, Keiko; Katakami, Hatsue; Hyun-Jung Kim; et al. (August 2007). "Epigenetic Inheritance in Rice Plants". Annals of Botany. 100 (2): 205–217. doi:10.1093/aob/mcm110. PMC 2735323. PMID 17576658.

- ↑ Sano, Hiroshi (April 2010). "Inheritance of acquired traits in plants: Reinstatement of Lamarck". Plant Signaling & Behavior. 5 (4): 346–348. doi:10.4161/psb.5.4.10803. PMC 2958583. PMID 20118668.

- ↑ Singer, Emily (February 4, 2009). "A Comeback for Lamarckian Evolution?". MIT Technology Review (Biomedicine news).

- ↑ Rechavi, Oded; Minevich, Gregory; Hobert, Oliver (December 9, 2011). "Transgenerational Inheritance of an Acquired Small RNA-Based Antiviral Response in C. Elegans". Cell. 147 (6): 1248–1256. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.042. PMC 3250924. PMID 22119442.

- ↑ Rechavi, O.; Houri-Ze'evi, L.; Anava, S.; Goh, W.S.; Kerk, S.Y.; Hannon, G.J.; Hobert, O. (17 July 2014). "Starvation-induced transgenerational inheritance of small RNAs in C. elegans". Cell. 158 (2): 277–287. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2014.06.020. PMC 4377509. PMID 25018105.

- ↑ Handel, Adam E.; Ramagopalan, Sreeram V. (May 13, 2010). "Is Lamarckian evolution relevant to medicine?". BMC Medical Genetics. 11: 73. doi:10.1186/1471-2350-11-73. PMC 2876149. PMID 20465829.

- 1 2 Springer & Holley 2013, p. 94

- ↑ Koonin, Eugene V.; Wolf, Yuri I. (November 11, 2009). "Is evolution Darwinian or/and Lamarckian?". Biology Direct. 4: 42. doi:10.1186/1745-6150-4-42. PMC 2781790. PMID 19906303.

- ↑ Coyne, Jerry (October 24, 2010). "Epigenetics: the light and the way?". Why Evolution Is True (Blog). Retrieved 2015-11-04.

- ↑ Coyne, Jerry (September 23, 2013). "Epigenetics smackdown at the Guardian". Why Evolution is True (Blog). Retrieved 2015-11-04.

- ↑ González-Recio O, Toro MA, Bach A. (2015). Past, present, and future of epigenetics applied to livestock breeding. Front Genet 6: 305.

- ↑ Varona L, Munilla S, Mouresan EF, González-Rodríguez A, Moreno C, Altarriba J. (2015). A Bayesian model for the analysis of transgenerational epigenetic variation. G3: Genes, Genomes, Genetics 5(4): 477-485.

- ↑ Haig, David (June 2007). "Weismann Rules! OK? Epigenetics and the Lamarckian temptation". Biology and Philosophy. 22 (3): 415–428. doi:10.1007/s10539-006-9033-y.

Modern neo-Darwinists do not deny that epigenetic mechanisms play an important role during development nor do they deny that these mechanisms enable a variety of adaptive responses to the environment. Recurrent, predictable changes of epigenetic state provide a useful set of switches that allow genetically-identical cells to acquire differentiated functions and allow facultative responses of a genotype to environmental changes (provided that 'similar' changes have occurred repeatedly in the past). However, most neo-Darwinists would claim that the ability to adaptively switch epigenetic state is a property of the DNA sequence (in the sense that alternative sequences would show different switching behavior) and that any increase of adaptedness in the system has come about by a process of natural selection.

- ↑ Haig, David (November 2011). "Lamarck Ascending!". Philosophy & Theory in Biology (Book essay). City University of New York, Lehman College. 3 (e204). doi:10.3998/ptb.6959004.0003.004. "A Review of Transformations of Lamarckism: From Subtle Fluids to Molecular Biology, edited by Snait B. Gissis and Eva Jablonka, MIT Press, 2011"

- ↑ Dickins, Thomas E.; Rahman, Qazi (August 7, 2012). "The extended evolutionary synthesis and the role of soft inheritance in evolution". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 279 (1740): 2913–2921. doi:10.1098/rspb.2012.0273. PMC 3385474. PMID 22593110.

- 1 2 3 4 Bowler, Peter J., Peter J. (1989). Evolution: The History of an Idea (Revised ed.). University of California Press. pp. 179, 341. ISBN 9780520063860.

- ↑ Whitelaw, Emma (March 27, 2015). "Disputing Lamarckian Epigenetic Inheritance in Mammals". Genome Biology. 16 (60): 60. doi:10.1186/s13059-015-0626-0. PMC 4375926. PMID 25853737.

- ↑ Weiss, Adam (October 2015). "Lamarckian Illusions". Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 30 (10): 566–568. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2015.08.003. PMID 26411613.

- ↑ Steele, E.J. (2016). "Somatic hypermutation in immunity and cancer: Critical analysis of strand-biased and codon-context mutation signatures". DNA Repair. 45: 1–24. doi:10.1016/j.dnarep.2016.07.001. PMID 27449479.

- ↑ Steele, E.J.; Pollard, J.W. (1987). "Hypothesis : Somatic Hypermutation by gene conversion via the error prone DNA-to-RNA-to-DNA information loop". Molecular Immunology. 24: 667–673. doi:10.1016/j.dnarep.2016.07.001. PMID 2443841.

- ↑ Steele, Lindley & Blanden 1998

- 1 2 Moran, Nancy A.; Sloan, Daniel B. (2015-12-04). "The Hologenome Concept: Helpful or Hollow?". PLOS Biology. Public Library of Science (PLoS). 13 (12): e1002311. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1002311.

- ↑ Rosenberg, Eugene; Sharon, Gill; Zilber-Rosenberg, Ilana (December 2009). "The hologenome theory of evolution contains Lamarckian aspects within a Darwinian framework". Environmental Microbiology. 11 (12): 2959–2962. doi:10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.01995.x. PMID 19573132.

- ↑ Depew, David J. (2003), "Baldwin Boosters, Baldwin Skeptics" in: Weber, Bruce H.; Depew, David J. (2003). Evolution and learning: The Baldwin effect reconsidered. MIT Press. pp. 3–31. ISBN 0-262-23229-4.

- ↑ Simpson, George Gaylord (1953). "The Baldwin effect". Evolution. 7 (2): 110–117. doi:10.2307/2405746.

- ↑ Dennett, Daniel (2003), "The Baldwin Effect, a Crane, not a Skyhook" in: Weber, Bruce H.; Depew, David J. (2003). Evolution and learning: The Baldwin effect reconsidered. MIT Press. pp. 69–106. ISBN 0-262-23229-4.

- ↑ Cullen 2000, pp. 31–60

Bibliography

- Aminoff, Michael J. (2011). Brown-Séquard: An Improbable Genius Who Transformed Medicine. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-974263-9. LCCN 2010013439. OCLC 680002156.

- Baird, Davis; Scerri, Eric; McIntyre, Lee, eds. (2006). Philosophy of Chemistry: Synthesis of a New Discipline. Boston Studies in the Philosophy of Science. 242. Springer. ISBN 978-1-4020-3256-1. LCCN 2006295950. OCLC 209927684.

- Bateson, William (1913). Problems of Genetics. Yale University Press. LCCN 13021769. OCLC 809326988. Problems of genetics (1913) on the Internet Archive

- Blumberg, Mark S. (2010). Freaks of Nature: And What They Tell Us about Evolution and Development (Paperback ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-921306-1. LCCN 2010481198. OCLC 352916350.

- Boesiger, Ernest (1974). "Evolutionary theories after Lamarck and Darwin". In Ayala, Francisco José; Dobzhansky, Theodosius. Studies in the Philosophy of Biology: Reduction and Related Problems. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-02649-7. LCCN 73090656. OCLC 1265669.

- Bowler, Peter J. (1992) [Original hardback edition published 1983]. The Eclipse of Darwinism: Anti-Darwinian Evolution Theories in the Decades Around 1900 (Johns Hopkins Paperbacks ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-4391-X. LCCN 82021170. OCLC 611262030.

- Bowler, Peter J. (2003). Evolution: The History of an Idea (3rd ed.). University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-23693-9. LCCN 2002007569. OCLC 49824702.

- Bowler, Peter J. (2013). Darwin Deleted: Imagining a World Without Darwin. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-06867-1. LCCN 2012033769. OCLC 808010092.

- Burkhardt, Richard W., Jr. (1995) [Originally published 1977]. The Spirit of System: Lamarck and Evolutionary Biology: Now with 'Lamarck in 1995' (First Harvard University Press paperback ed.). Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-83318-X. LCCN 95010861. OCLC 32396741.

- Cannon, Herbert Graham (1975) [Originally published 1959: Manchester, England; Manchester University Press]. Lamarck and Modern Genetics (Reprint ed.). Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-8371-8173-9. LCCN 75010211. OCLC 1418716.

- Child, Charles Manning (1945). Biographical Memoir of Francis Bertody Sumner, 1874–1945 (PDF). National Academy of Sciences, Washington, D.C. Biographical Memoirs. 25. National Academy of Sciences. LCCN 52004656. OCLC 11852074. Retrieved 2015-10-27.

- Cock, Alan G.; Forsdyke, Donald R. (2008). Treasure Your Exceptions: The Science and Life of William Bateson. Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-75687-5. LCCN 2008931291. OCLC 344846261.

- Cullen, Ben Sandford (2000). Steele, James; Cullen, Richard; Chippindale, Christopher, eds. Contagious Ideas: On Evolution, Culture, Archaeology, and Cultural Virus Theory. Oxbow Books. ISBN 1-84217-014-7. OCLC 47122736.

- Cunningham, Joseph Thomas (1928). Modern Biology: A Review of the Principal Phenomena of Animal Life in Relation to Modern Concepts and Theories. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co., Ltd. LCCN 29000027. OCLC 920415.

- Darwin, Erasmus (1794–1796). Zoonomia; or, the Laws of Organic Life. Joseph Johnson. LCCN 34036671. OCLC 670735211.

- Delage, Yves; Goldsmith, Marie (1912). The Theories of Evolution. Translation by André Tridon. B. W. Huebsch. LCCN 12031796. OCLC 522024. The theories of evolution (1912) on the Internet Archive

- Desmond, Adrian; Moore, James R. (1991). Darwin. Michael Joseph; Viking Penguin. ISBN 0-7181-3430-3. LCCN 92196964. OCLC 26502431.

- Forel, Auguste (1934) [1922]. The Sexual Question: A Scientific, Psychological, Hygienic and Sociological Study. English adaptation from the second German edition, revised and enlarged by C. F. Marshall (Revised ed.). Physicians and Surgeons Book Company. LCCN 22016399. OCLC 29326677. The sexual question: a scientific, psychological, hygienic and sociological study (1922) on the Internet Archive. Retrieved 2015-10-26.

- Gardner, Martin (1957) [1952]. Fads and Fallacies in the Name of Science. Dover Publications. LCCN 57003844. OCLC 233892.

- Goldschmidt, Richard (1940). The Material Basis of Evolution. Mrs. Hepsa Ely Silliman Memorial Lectures. Yale University Press; Oxford University Press. LCCN 40012233. OCLC 595767401.

- Gould, Stephen Jay (1980). The Panda's Thumb: More Reflections in Natural History (1st ed.). W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-01380-4. LCCN 80015952. OCLC 6331415.

- Gould, Stephen Jay (2002). The Structure of Evolutionary Theory. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-00613-5. LCCN 2001043556. OCLC 47869352.

- Hagen, Joel B. (2002). "Retelling Experiments: H.B.D. Kettlewell's Studies of Industrial Melanism in Peppered Moths". In Giltrow, Janet. Academic Reading: Reading and Writing Across the Disciplines (2nd ed.). Broadview Press. ISBN 1-55111-393-7. LCCN 2002514564. OCLC 46626903.

- Harwood, Jonathan (1993). Styles of Scientific Thought: The German Genetics Community, 1900–1933. Science and its Conceptual Foundations. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-31882-6. LCCN 92015321. OCLC 25746714.

- Jablonka, Eva; Lamb, Marion J. (1995). Epigenetic Inheritance and Evolution: The Lamarckian Dimension. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-854062-0. LCCN 94032108. OCLC 30974876.

- Kohler, Robert E. (2002). Landscapes and Labscapes: Exploring the Lab-Field Border in Biology. University Of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-45010-4. LCCN 2002023331. OCLC 690162738.

- Lamarck, Jean-Baptiste (1830) [Originally published 1809; Paris: Dentu et L'Auteur]. Philosophie Zoologique (in French) (New ed.). Germer Baillière. LCCN 11003671.

Philosophie zoologique (1830) on the Internet Archive. Retrieved 2015-10-22.

- —— (1914). Zoological Philosophy; An Exposition with Regard to the Natural History of Animals. Translated, with an introduction, by Hugh Elliot. Macmillan and Co., Ltd. LCCN a15000196. OCLC 1489850. Zoological philosophy (1914) on the Internet Archive. Retrieved 2015-10-23.

- Linville, Henry R.; Kelly, Henry A. (1906). A Text-Book in General Zoölogy. Ginn & Company. LCCN 06023318. OCLC 1041858. A textbook in general zoölogy (1906) on the Internet Archive. Retrieved 2015-10-27.

- Mason, Stephen Finney (1956). Main Currents of Scientific Thought: A History of the Sciences. The Life of Science Library. 32 (Reprint ed.). Abelard-Schuman. OCLC 732176237.

- Mayr, Ernst (1997) [Originally published 1976]. Evolution and the Diversity of Life: Selected Essays (First Harvard University Press paperback ed.). Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-27105-X. LCCN 75042131. OCLC 247687824.

- Mayr, Ernst; Provine, William B., eds. (1998). The Evolutionary Synthesis: Perspectives on the Unification of Biology. New preface by Ernst Mayr. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-27226-9. LCCN 98157613. OCLC 503188713.

- McDougall, William (1934). Modern Materialism and Emergent Evolution. Methuen.

- Medawar, Peter (1985) [Originally published 1983]. Aristotle to Zoos: A Philosophical Dictionary of Biology. Oxford Paperbacks (Reprint ed.). Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-19-283043-0. LCCN 84016529. OCLC 11030267.

- Mitman, Gregg (1992). The State of Nature: Ecology, Community, and American Social Thought, 1900–1950. Science and its Conceptual Foundations. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-53236-4. LCCN 91045638. OCLC 25130594.

- Moore, David S. (2015). The Developing Genome: An Introduction to Behavioral Epigenetics. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-992234-5. LCCN 2014049505. OCLC 894139943.

- Moore, Randy; Decker, Mark D. (2008). More Than Darwin: An Encyclopedia of the People and Places of the Evolution-creationism Controversy. Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-34155-7. LCCN 2007044406. OCLC 177023758.

- Moore, James R., ed. (2002) [Originally published 1989]. History, Humanity and Evolution: Essays for John C. Greene. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-52478-4. LCCN 89032583. OCLC 49784849.

- Morgan, Thomas Hunt (1903). Evolution and Adaptation. The Macmillan Company; Macmillan and Co., Ltd. LCCN 03027216. OCLC 758217701. Evolution and adaptation (1903) on the Internet Archive

- Mumford, Frederick Blackmar (1921) [Originally published 1917]. The Breeding of Animals. The Rural Text-Book Series. The Macmillan Company. LCCN 17007834. OCLC 5429719. The breeding of animals (1921) on the Internet Archive

- Newman, Horatio Hackett (1921). Readings in Evolution, Genetics, and Eugenics. University of Chicago Press. LCCN 21017204. OCLC 606993. Readings in evolution, genetics, and eugenics (1921) on the Internet Archive

- Otho S. A. Sprague Memorial Institute (1940). Studies from the Otho S. A. Sprague Memorial Institute: Collected Reprints. 25. Otho S. A. Sprague Memorial Institute. OCLC 605547177.

- Quammen, David (2006). The Reluctant Mr. Darwin: An Intimate Portrait of Charles Darwin and the Making of His Theory of Evolution. Great Discoveries (1st ed.). Atlas Books/Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-05981-6. LCCN 2006009864. OCLC 65400177.

- Raitiere, Martin N. (2012). The Complicity of Friends: How George Eliot, G. H. Lewes, and John Hughlings-Jackson Encoded Herbert Spencer's Secret. Bucknell University Press. ISBN 978-1-61148-418-2. LCCN 2012030762. OCLC 806981125.

- Rignano, Eugenio (1906). Sur La Transmissibilité Des Caractères Acquis: Hypothèse D'une Centro-épigénèse (in French). Félix Alcan. OCLC 5967582.

- ——; Harvey, Basil C. H. (1911). Eugenio Rignano Upon the Inheritance of Acquired Characters: A Hypothesis of Heredity, Development, and Assimilation. Authorized English translation by Basil C. H. Harvey. Open Court Publishing Company. LCCN 11026509. OCLC 1311084. Eugenio Rignano upon the inheritance of acquired characters (1911) on the Internet Archive

- Rignano, Eugenio (1926). Biological Memory. International Library of Psychology, Philosophy, and Scientific Method. Translated with an introduction by Ernest MacBride. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co.; Harcourt, Brace & Company. LCCN 26009586. OCLC 811731.

- Simpson, George Gaylord (1944). Tempo and Mode in Evolution. Columbia Biological Series. 15. Columbia University Press. LCCN a45000404. OCLC 993515.

- Simpson, George Gaylord (1964). This View of Life: The World of an Evolutionist (1st ed.). Harcourt, Brace & World. LCCN 64014636. OCLC 230986.

- Simpson, George Gaylord (1965). Life: An Introduction to Biology (2nd ed.). Harcourt, Brace & World. LCCN 65014384. OCLC 165951.

- Springer, Joseph T.; Holley, Dennis (2013). An Introduction to Zoology (1st ed.). Jones & Bartlett Learning. ISBN 978-1-4496-4891-6. LCCN 2011022399. OCLC 646112356.

- Steele, Edward J.; Lindley, Robyn A.; Blanden, Robert V. (1998). Lamarck's Signature : How Retrogenes Are Changing Darwin's Natural Selection Paradigm. Helix Books; Frontiers of Science. Perseus Books. ISBN 0-7382-0014-X. LCCN 98087900. OCLC 40449772.

- Weismann, August (1889). Poulton, Edward B.; Schönland, Selmar; Shipley, Arthur E., eds. Essays Upon Heredity and Kindred Biological Problems. Clarendon Press. LCCN 77010494. OCLC 488543825. Retrieved 2015-10-30.

- Wilkins, John S. (2009) [Originally published 2001 in Laurent, John; Nightingale, John (eds), Darwinism and Evolutionary Economics, chapter 8, pp. 160–183; Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar]. "The Appearance of Lamarckism in the Evolution of Culture". In Hodgson, Geoffrey M. Darwinism and Economics. The International Library of Critical Writings in Economics Series. 233. Edward Elgar. ISBN 978-1-84844-072-2. LCCN 2008939772. OCLC 271774708.

- Wood, Bernard, ed. (2013). Wiley-Blackwell Encyclopedia of Human Evolution (First paperback ed.). Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-118-65099-8. LCCN 2013012756. OCLC 841039552.

- Young, Robert Thompson (1922). Biology in America. R.G. Badger. LCCN 22019903. OCLC 370597. Biology in America (1922) on the Internet Archive

Further reading

- Barthélemy-Madaule, Madeleine (1982). Lamarck, the Mythical Precursor: A Study of the Relations Between Science and Ideology. English translation by M. H. Shank. MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-02179-X. LCCN 82010061. OCLC 8533097. Translation of Lamarck, ou, Le mythe du précurseur (1979)

- Bowler, Peter J. (1989). The Mendelian Revolution: The Emergence of Hereditarian Concepts in Modern Science and Society. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-3888-6. LCCN 89030914. OCLC 19322402.

- Burkeman, Oliver (19 March 2010). "Why everything you've been told about evolution is wrong". The Guardian. Guardian Media Group.

- Rutherford, Adam (19 March 2010). "Beyond a 'Darwin was wrong' headline". The Guardian.

- Cook, George M. (December 1999). "Neo-Lamarckian Experimentalism in America: Origins and Consequences". The Quarterly Review of Biology. 74 (4): 417–437. doi:10.1086/394112. JSTOR 2664721. PMID 10672643.

- Desmond, Adrian (1989). The Politics of Evolution: Morphology, Medicine, and Reform in Radical London. Science and its Conceptual Foundations. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-14346-5. LCCN 89005137. OCLC 709606191.

- Fecht, Sarah (October 19, 2011). "Longevity Shown for First Time to Be Inherited via a Non-DNA Mechanism". Scientific American. Retrieved 2015-11-05.

- Gissis, Snait B.; Jablonka, Eva., eds. (2011). Transformations of Lamarckism: From Subtle Fluids to Molecular Biology. Vienna Series in Theoretical Biology. Illustrations by Anna Zeligowski. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-01514-1. LCCN 2010031344. OCLC 662152397.

- Honeywill, Ross (2008). Lamarck's Evolution: Two Centuries of Genius and Jealousy. Pier 9. ISBN 978-1-921208-60-7. LCCN 2011431766. OCLC 746154950.

- Jablonka, Eva; Lamb, Marion J. (2008). "The Epigenome in Evolution: Beyond The Modern Synthesis" (PDF). Information Bulletin VOGiS. 12 (1/2): 242–254.

- Medawar, Peter (1990). Pyke, David, ed. The Threat and the Glory: Reflections on Science and Scientists. Foreword by Lewis Thomas (1st U.S. ed.). HarperCollins. ISBN 0-06-039112-X. LCCN 89046107. OCLC 21977349. Contains the BBC Reith Lectures "The Future of Man."

- Molino, Jean (2000). "Toward an Evolutionary Theory of Music and Language". In Wallin, Nils L.; Merker, Björn; Brown, Steven. The Origins of Music. MIT Press. pp. 165–176. ISBN 0-262-23206-5. LCCN 98054088. OCLC 44963330. "Consists of papers given at a workshop on the origins of music held in Fiesole, Italy, May 1997, the first of a series called Florentine Workshops in Biomusicology."

- Peng, Wayne (December 27, 2011). "Lamarckian viral defense in worms". Nature Genetics. 44: 15. doi:10.1038/ng.1062.

- Pennisi, Elizabeth (September 6, 2013). "Evolution Heresy? Epigenetics Underlies Heritable Plant Traits". Science. 341 (6150): 1055. doi:10.1126/science.341.6150.1055. PMID 24009370.

- Persell, Stuart (1999). Neo-Lamarckism and the Evolution Controversy in France, 1870-1920. Studies in French Civilization. 14. Edwin Mellen Press. ISBN 0-7734-8275-X. LCCN 98048633. OCLC 40193707.

- Seki, Yoshiyuki (April 2013). Groszmann, Roberto J.; Iwakiri, Yasuko; Taddei, Tamar H., eds. "Serum-mediated transgenerational effects on sperm: Evidence for lamarckian inheritance?". Hepatology. 57 (4): 1663–1665. doi:10.1002/hep.26240. PMID 23568276.

- Waddington, Conrad H. (1961). "The Human Evolutionary System". In Banton, Michael. Darwinism and the Study of Society: A Centenary Symposium; Chicago, IL. Tavistock Publications; Quadrangle Books. LCCN 61007932. OCLC 1003950. "Essays ... based upon papers read at a conference held at the University of Edinburgh ... 1959."

- Ward, Lester Frank (1891). Neo-Darwinism and Neo-Lamarckism. Press of Gedney & Roberts. LCCN 07037459. OCLC 4115244. "Annual address of the president of the Biological Society of Washington. Delivered January 24, 1891. (From the Proceedings, vol. VI.)" Neo-Darwinism and neo-Lamarckism (1891) on the Internet Archive.

- Whitelaw, Emma (February 2006). "Epigenetics: Sins of the fathers, and their fathers". European Journal of Human Genetics. Nature Publishing Group on behalf of the European Society of Human Genetics. 14 (2): 131–132. doi:10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201567. PMID 16421606.

- Yongsheng Liu (September 2007). "Like father like son. A fresh review of the inheritance of acquired characteristics". EMBO Reports. 8 (9): 798–803. doi:10.1038/sj.embor.7401060. PMC 1973965. PMID 17767188.

External links

- "Jean-Baptiste Lamarck : works and heritage". Retrieved 2015-11-07. — An English/French web site edited by Pietro Corsi (Oxford Univ.) and realised by CNRS (France - IT team of CRHST). This web site contents all books, texts, manuscripts and Lamarck's Herbarium.

- Waggoner, Ben; Speer, Brian (February 25, 2006). "Jean-Baptiste Lamarck (1744-1829)". Evolution. University of California Museum of Paleontology. Retrieved 2010-07-03.