''Leyla Express'' and ''Johnny Express'' incidents

In December 1971, the freighters Leyla Express and Johnny Express were seized by Cuban gunboats off the coast of Cuba. The Leyla Express was stopped off the Cuban coast on December 5: the Johnny Express was intercepted by gunboats of the island of Little Inagua in the Bahamas ten days later. Some of the crew of the Johnny Express, including the captain, were injured when the gunboats fired on their vessel. The freighters both carried Panamanian flags of convenience, but belonged to the Bahama Lines corporation, based in Miami. The company was run by four brothers, Cuban exiles who had previously been involved in activities directed against the Cuban government. Cuba stated that both vessels were being used by the US Central Intelligence Agency to transport weapons, explosives, and personnel to Cuba, and accused the ships of piracy. Cuba had suspected the involvement of one of Bahama Lines ships in shelling the Cuban village of Samá, on the northern coast of Oriente Province, a few months previously; several civilians had died in the attack. The US government and the Bahama Lines denied the accusations.

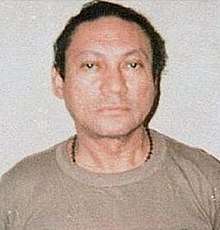

Cuba released the crew of both ships to Panamanian custody, but announced that José Villa, the captain of the Johnny Express, would face trial as he had confessed to being an agent of the US Central Intelligence Agency. The US asked the Panamanian government of Omar Torrijos to negotiate his release. Rómulo Escobar Bethancourt and Manuel Noriega traveled to Cuba, where they negotiated Villa's release into Panamanian custody, in return for which criminal charges were brought against Villa in Panama, though he was released without being convicted. The success of the negotiations undertaken by Noriega were later used by him to bargain with the US government. As a consequence of the incident, the US ordered all its naval and air forces in the region to go to the aid of any ships coming under attack from Cuban vessels. A Panamanian mission which investigated the incident concluded, based on the ships logs, that the vessels had in fact brought insurgent forces to Cuban territory, and that the Cuban government's accusations were accurate.

Background

.png)

The Johnny Express and the Leyla Express (also described as the Lyle Express,[1] the Lalia Express,[2] and the Lyla Express[3]) were two Miami-based freighters flying Panamanian flags of convenience.[4] They were owned by the Bahama Lines corporation, based in Miami, which also ran four other freighters. The corporation belonged to four brothers from the Babún family: all four were Cuban exiles.[1] The Miami Herald reported that all four had been involved in activities directed against Fidel Castro. Among Cuban exiles in Miami, Santiago Babún, one of the brothers, was believed to have been an agent of the United States Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) while in Cuba.[5] According to reporter John Dinges, a long-term correspondent on Latin America for the US media, both freighters were being used by Cuban exiles to launch machine-gun attacks on Cuban government targets.[4] Verne Lyon, a one-time CIA agent, wrote in his memoir that the two boats were run by the CIA, and referred to the Johnny Express as a CIA "mother ship".[6] A 1997 biography of George H. W. Bush, in discussing his relationship with Manuel Noriega, also stated that the two freighters had been used to launch speed-boat attacks against Cuba.[7]

Vessel seizures

The Cuban government believed that a boat owned by one of the brothers was responsible for shelling the Cuban village of Samá, on the northern coast of Oriente Province, in October 1971; several people were reported to have been killed in the attack.[1] Several months before December 1971, the Bahamas Lines were reported to have complained to the US government that their ships were being followed by Cuban vessels.[5] The company stated that the US Coast guard had been notified of every incident, but that it had not taken any action.[8] On December 5, 1971, the Leyla Express was stopped by Cuban government vessels off the coast of Cuba, and escorted to the Cuban port of Baracoa. The Cuban government stated that the ship was being used to transport weapons and agents by the CIA, and added that the Leyla Express had been used to land explosives, men, and weapons on Cuban shores three times in 1968 and 1969.[5] The Cuban government called the vessel a pirate ship, and said that the 14 members of the freighter's crew would face criminal charges.[3][5][9]

On December 15, 1971, the Johnny Express was attacked by a Cuban Gunboat, seized, and taken to a Cuban port. The attack occurred in the territorial waters of the Bahamas, near the island of Little Inagua.[3][5] According to officials of the Bahama Lines, the freighter had left Port-au-Prince in Haiti the previous day. At the time of its capture, the Johnny Express was approximately 120 miles (190 km) from the Cuban coast. The 235-foot ship was carrying a crew of 11: its captain, José Villa, was a Cuban-born naturalized US citizen.[5][2][8] The Miami Herald reported that Villa had an approximately three-hour-long conversation on the radio with the office of the Bahama Lines, beginning at approximately 11:35 AM on December 15, when Villa radioed saying he was being followed by a gunboat, in response to which he had changed course northwards. He then reported that he had been ordered to heave to; the company stated that it had asked Villa to continue on his way, because he was in international waters.[5] At 1:31 PM, Villa reported that the gunboat had opened fire, and that he himself had been wounded. Further reports of firing followed, including of shots fired at the radio antenna, and of the gunboat ramming the freighter. The final report, at 2:40 PM, stated that the freighter was taking on water.[5] A later report, attributed to the US State Department, stated that the Johnny Express was being towed to Cuba.[5] Lyon writes that the Cuban gunboat eventually rammed the Johnny Express, boarded her, and towed her to Cuba, where the wounded crew members were treated.[6] US diplomat William Jorden wrote in 2014 that the wounded crew members were transported by the Cuban gunboat to Havana for treatment, while the Johnny Express was taken to the port of Mariel.[10]

Reactions and negotiations

The Cuban government described the actions of both freighters as acts of piracy.[3] It stated that it would attack pirate ships regardless of the distance of the ship from Cuba, or the flag the ship was carrying.[1] Castro criticized the "landing of weapons, organization of mercenary bands, infiltration of spies, saboteurs, [and] arm drops of all kinds," and stated that the Cuban government had been forced to spend a lot of money and resources to combat these efforts.[9] Teófilo Babún, one of the owners of the Bahamas Lines, denied that the ships were engaged in piracy, and stated that they were commercial vessels that did not carry any weapons. A spokesperson for the US Department of State also said that the vessels had no connection to the US government.[1][5] A day later, the US government responded stating that it would "all measures under international law" to protect ships in the Caribbean, including those of other nations, from Cuban attacks.[1] According to Verne, in response to US allegations that it had engaged in piracy, the Cuban government released photographs of a fast boat carried by the Johnny Express which had been used to land weapons and men on Cuban shores.[6] The New York Times reported that the US naval and air forces in the Caribbean had been ordered to support any vessel attacked by Cuba. US President Richard Nixon told José Villa's wife Isabel that he would do his best to get her husband released. The US issued a demand to Cuba, via the Swiss embassy in Havana, that Villa be released; Cuba did not respond to the request.[1]

The crews of both ships were eventually handed over to the government of Panama. José Villa, however, initially remained in Cuban custody; he faced trial as a result of having reportedly confessed to being an agent of the CIA.[3][9] The US government asked Omar Torrijos, the leader of Panama, to send a mission to Cuba to mediate the conflict. Torrijos agreed, though Cuba and Panama did not have diplomatic relations at the time.[11] According to Dinges, at approximately the same time, the CIA station in Panama City was ordered to send Manuel Noriega on the mission as a personal emissary of Torrijos. Noriega was then a member of Torrijos government. His relationship with the US intelligence services, which had been on a case-by-case basis until then, was regularized in 1971.[12][13]

The formal mission to Cuba was led by Rómulo Escobar Bethancourt, a communist member of Torrijos's government, but Noriega accompanied him.[11] According to Dinges, sources within the US intelligence services stated that it was Noriega's presence which convinced Cuban leader Fidel Castro to release Villa into Panamanian custody.[11] Historian Herbert Parmet wrote that Noriega played an important, and possibly decisive, role in the negotiations.[7] Villa was taken to Panama, where in accordance with the agreement with Castro, charges of espionage were brought against Villa. After a delay, described by Dinges as being long enough to "save face all around", Villa was freed and allowed to return to the US.[11]

Investigation and aftermath

A commission from Panama subsequently visited Cuba to investigate the case. Based on examinations of the ships log books, the commission concluded that the ships had in fact been engaged in bringing insurgent forces to Cuban territory, and that the Cuban government's charges were accurate.[3] A case study of the incident, reported in the US Army journal Military Law Review, found that since the actions of the two ships had the objective of overthrowing the Cuban government, they constituted political actions, and therefore could not be considered acts of piracy.[3] The negotiations carried out by Manuel Noriega were the most substantial assistance he had given the US government up to that point; he and Torrijos would use the success of the mission to bargain with in subsequent negotiations with the US.[11] According to Jorden, it was ironic that Noriega was introduced to Castro at the behest of the US; Noriega would have prolonged relations with Castro's government, including selling it intelligence while simultaneously being employed by the CIA.[14][15][10] In April 1972, as a consequence of the Johnny Express incident, the US ordered all of its warships in the Caribbean region to assist ships from any country friendly to the US, should they come under attack from Cuban ships.[2][16]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Szulc, Tad (December 18, 1971). "US Warns Cuba on Ship Attacks". The New York Times. Retrieved May 27, 2018.

- 1 2 3 Petrie, John N. (December 1996). American Neutrality in the 20th Century: The Impossible Dream. DIANE Publishing. pp. 111–112. ISBN 978-0-7881-3682-5.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Behuniak, Thomas E. (Fall 1978). "The Seizure and Recovery of the S.S. Mayaguez: A Legal Analysis of United States Claims, Part 1" (PDF). Military Law Review. 82: 98–100. Retrieved May 28, 2018.

- 1 2 Dinges 1990, p. 69.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Montalbano, William (December 16, 1971). "Cuban Boat Fires on, Rams Miami Ship, Captain Radios". Miami Herald. Retrieved May 27, 2018.

- 1 2 3 Lyon, Verne; Zwerling, Philip (January 18, 2018). Eyes on Havana: Memoir of an American Spy Betrayed by the CIA. McFarland. p. 127. ISBN 978-1-4766-7090-4.

- 1 2 Parmet, Herbert S. (1997). George Bush: The Life of a Lone Star Yankee. Transaction Publishers. pp. 202–3. ISBN 978-1-4128-2452-1.

- 1 2 "Freighter Is Reported Attacked And Seized by Cuban Gunboat". The New York Times. Associated Press. December 16, 1971. Retrieved May 29, 2018.

- 1 2 3 Franklin, Jane (May 2016). Cuba and the U.S. Empire: A Chronological History. NYU Press. p. 98. ISBN 978-1-58367-606-6.

- 1 2 Jorden, William J. (March 1, 2014). Panama Odyssey. University of Texas Press. p. 257. ISBN 978-0-292-71801-2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Dinges 1990, p. 70.

- ↑ Johnston, Davis (January 19, 1991). "U.S. Admits Payments to Noriega". New York Times. Retrieved June 7, 2017.

- ↑ Dinges 1990, pp. 49–52.

- ↑ Hersh, Seymour (June 12, 1986). "Panama Strongman Said to Trade in Drugs, Arms, and Illegal Money". New York Times. Retrieved June 6, 2017.

- ↑ Dinges 1990, pp. 70–71.

- ↑ Welles, Benjamin (April 14, 1972). "Nixon Gave Navy Power To Halt Cuba's Seizures". The New York Times. Retrieved May 29, 2018.

Sources

- Dinges, John (1990). Our Man in Panama. New York City: Random House. ISBN 978-0-8129-1950-9.

.svg.png)