Johann Bernoulli

| Johann Bernoulli | |

|---|---|

Johann Bernoulli (portrait by Johann Rudolf Huber, circa 1740) | |

| Born |

6 August 1667 Basel, Switzerland |

| Died |

1 January 1748 (aged 80) Basel, Switzerland |

| Residence | Switzerland |

| Nationality | Swiss |

| Alma mater |

University of Basel (M.D., 1694) |

| Known for |

Development of infinitesimal calculus Catenary solution Bernoulli's rule Bernoulli's identity Brachistochrone problem |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Mathematics |

| Institutions |

University of Groningen University of Basel |

| Thesis | Dissertatio de effervescentia et fermentatione; Dissertatio Inauguralis Physico-Anatomica de Motu Musculorum (On the Mechanics of Effervescence and Fermentation and on the Mechanics of the Movement of the Muscles) (1694 (1690)[1]) |

| Doctoral advisor | Jacob Bernoulli |

| Other academic advisors | Nikolaus Eglinger |

| Doctoral students |

Daniel Bernoulli Leonhard Euler Johann Samuel König Pierre Louis Maupertuis |

| Other notable students | Guillaume de l'Hôpital |

| Notes | |

|

Brother of Jacob Bernoulli, and the father of Daniel Bernoulli. | |

Johann Bernoulli (also known as Jean or John; 6 August [O.S. 27 July] 1667 – 1 January 1748) was a Swiss mathematician and was one of the many prominent mathematicians in the Bernoulli family. He is known for his contributions to infinitesimal calculus and educating Leonhard Euler in the pupil's youth.

Early life and education

Johann was born in Basel, the son of Nicolaus Bernoulli, an apothecary, and his wife, Margaretha Schonauer and began studying medicine at Basel University. His father desired that he study business so that he might take over the family spice trade, but Johann Bernoulli did not like business and convinced his father to allow him to study medicine instead. However, Johann Bernoulli did not enjoy medicine either and began studying mathematics on the side with his older brother Jacob.[2] Throughout Johann Bernoulli's education at Basel University the Bernoulli brothers worked together spending much of their time studying the newly discovered infinitesimal calculus. They were among the first mathematicians to not only study and understand calculus but to apply it to various problems.[3]

Adult life

After graduating from Basel University Johann Bernoulli moved to teach differential equations. Later, in 1694, he married Dorothea Falkner and soon after accepted a position as the professor of mathematics at the University of Groningen. At the request of his father-in-law, Johann Bernoulli began the voyage back to his home town of Basel in 1705. Just after setting out on the journey he learned of his brother's death to tuberculosis. Johann Bernoulli had planned on becoming the professor of Greek at Basel University upon returning but instead was able to take over as professor of mathematics, his older brother's former position. As a student of Leibniz's calculus, Johann Bernoulli sided with him in 1713 in the Newton–Leibniz debate over who deserved credit for the discovery of calculus. Johann Bernoulli defended Leibniz by showing that he had solved certain problems with his methods that Newton had failed to solve. Johann Bernoulli also promoted Descartes' vortex theory over Newton's theory of gravitation. This ultimately delayed acceptance of Newton's theory in continental Europe.[4]

In 1724, Johann Bernoulli entered a competition sponsored by the French Académie Royale des Sciences, which posed the question:

- What are the laws according to which a perfectly hard body, put into motion, moves another body of the same nature either at rest or in motion, and which it encounters either in a vacuum or in a plenum?

In defending a view previously espoused by Leibniz, he found himself postulating an infinite external force required to make the body elastic by overcoming the infinite internal force making the body hard. In consequence, he was disqualified for the prize, which was won by Maclaurin. However, Bernoulli's paper was subsequently accepted in 1726 when the Académie considered papers regarding elastic bodies, for which the prize was awarded to Pierre Mazière. Bernoulli received an honourable mention in both competitions.

Private life

Although Jacob and Johann Bernoulli worked together before Johann graduated from Basel University, shortly after this, the two developed a jealous and competitive relationship. Johann was jealous of Jacob's position and the two often attempted to outdo each other. After Jacob's death Johann's jealousy shifted toward his own talented son, Daniel. In 1738 the father–son duo nearly simultaneously published separate works on hydrodynamics. Johann Bernoulli attempted to take precedence over his son by purposely and falsely predating his work two years prior to his son's.[5][6]

Johann married Dorothea Falkner, daughter of an Alderman of Basel. He was the father of Nicolaus II Bernoulli, Daniel Bernoulli and Johann II Bernoulli and uncle of Nicolaus I Bernoulli.

The Bernoulli brothers often worked on the same problems, but not without friction. Their most bitter dispute concerned finding the equation for the path followed by a particle from one point to another in the shortest time, if the particle is acted upon by gravity alone, a problem originally discussed by Galileo. In 1697 Jacob offered a reward for its solution. Accepting the challenge, Johann proposed the cycloid, the path of a point on a moving wheel, pointing out at the same time the relation this curve bears to the path described by a ray of light passing through strata of variable density. A protracted, bitter dispute then arose when Jacob challenged the solution and proposed his own. The dispute marked the origin of a new discipline, the calculus of variations.

L'Hôpital controversy

Bernoulli was hired by Guillaume de l'Hôpital for tutoring in mathematics. Bernoulli and l'Hôpital signed a contract which gave l'Hôpital the right to use Bernoulli's discoveries as he pleased. L'Hôpital authored the first textbook on infinitesimal calculus, Analyse des Infiniment Petits pour l'Intelligence des Lignes Courbes in 1696, which mainly consisted of the work of Bernoulli, including what is now known as l'Hôpital's rule.[7][8][9]

Subsequently, in letters to Leibniz, Varignon and others, Bernoulli complained that he had not received enough credit for his contributions, in spite of the fact that l'Hôpital acknowledged fully his debt in the preface of his book:

Je reconnais devoir beaucoup aux lumières de MM. Bernoulli, surtout à celles du jeune (Jean) présentement professeur à Groningue. Je me suis servi sans façon de leurs découvertes et de celles de M. Leibniz. C'est pourquoi je consens qu'ils en revendiquent tout ce qu'il leur plaira, me contentant de ce qu'ils voudront bien me laisser.

I recognize I owe much to the insights of the Messrs. Bernoulli, especially to those of the young (John), currently a professor in Groningen. I did unceremoniously use their discoveries, as well as those of Mr. Leibniz. For this reason I consent that they claim as much credit as they please, and will content myself with what they will agree to leave me.

Works

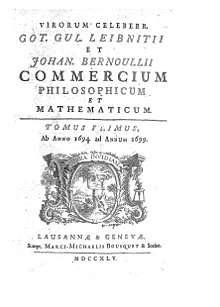

- Bernoulli, Johann (1742). [Opera]. 1 (in Latin). Lausannae & Genevae: Marc Michel & C Bousquet. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- Bernoulli, Johann (1742). [Opera]. 2 (in Latin). Lausannae & Genevae: Marc Michel & C Bousquet. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- Bernoulli, Johann (1742). [Opera]. 3 (in Latin). Lausannae & Genevae: Marc Michel & C Bousquet. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- Bernoulli, Johann (1742). [Opera]. 4 (in Latin). Lausannae & Genevae: Marc Michel & C Bousquet. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- Bernoulli, Johann (1786). Analyse de l'Opus Palatinum de Rheticus et du Thesaurus mathematicus de Pitiscus (in French). Parigi: sn. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- Bernoulli, Johann (1739). Dissertatio de ancoris (in Latin). Leipzig: sn. Retrieved 20 June 2018.

See also

References

- ↑ Published in 1690, submitted in 1694.

- ↑ Sanford, Vera (2008) [1958]. A Short History of Mathematics (2nd ed.). Read Books. ISBN 1-4097-2710-6. OCLC 607532308.

- ↑ The Bernoulli Family, by H. Bernhard, Doubleday, Page & Company, (1938)

- ↑ Fleckenstein, Joachim O. (1977) [1949]. Johann und Jakob Bernoulli (in German) (2nd ed.). Birkhäuser. ISBN 3764308486. OCLC 4062356.

- ↑ https://books.google.com/books?id=tIRBzdTWwyUC&pg=PA9&dq=Johann+Bernoulli+Hydrodynamics+antedate+1732

- ↑ https://books.google.com/books?id=9uf97reZZCUC&pg=PA133&dq=Johann+Bernoulli+predating+1732

- ↑ Maor, Eli (1998). e: The Story of a Number. Princeton University Press. p. 116. ISBN 0-691-05854-7. OCLC 29310868.

- ↑ Coolidge, Julian Lowell (1990) [1963]. The mathematics of great amateurs (2nd ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 154–163. ISBN 0-19-853939-8. OCLC 20418646.

- ↑ Struik, D. J. (1969). A Source Book in Mathematics: 1200–1800. Harvard University Press. pp. 312–6. ISBN 978-0-674-82355-6.

External links

- Johann Bernoulli at the Mathematics Genealogy Project

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Johann Bernoulli", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews .

- Golba, Paul, "Bernoulli, Johan'"

- "Johann Bernoulli"

- Weisstein, Eric Wolfgang (ed.). "Bernoulli, Johann (1667–1748)". ScienceWorld.

- Truesdell, C. (March 1958). "The New Bernoulli Edition". Isis. 49 (1): 54–62. doi:10.1086/348639. JSTOR 226604. discusses the strange agreement between Bernoulli and de l'Hôpital on pages 59–62.